Feb. 20—CLEVELAND — Throw a fishing line into Lake Erie today and the biggest creature you could hope to catch would be a sturgeon, a very rare lake resident which might reach seven feet long and weigh 200 pounds. Cast the same line into the water and the nastiest fish you might encounter is the sea lamprey, a parasitic vampire with a sucker-like mouth decked out with circular rows of sharp teeth, and a fish that likely would be attached to an unwitting host.

Today, the sturgeon and the lamprey qualify as big, and scary, respectively. But they look wimpy and tiny when compared to the apex predator that was the scourge of the waters here in a different era.

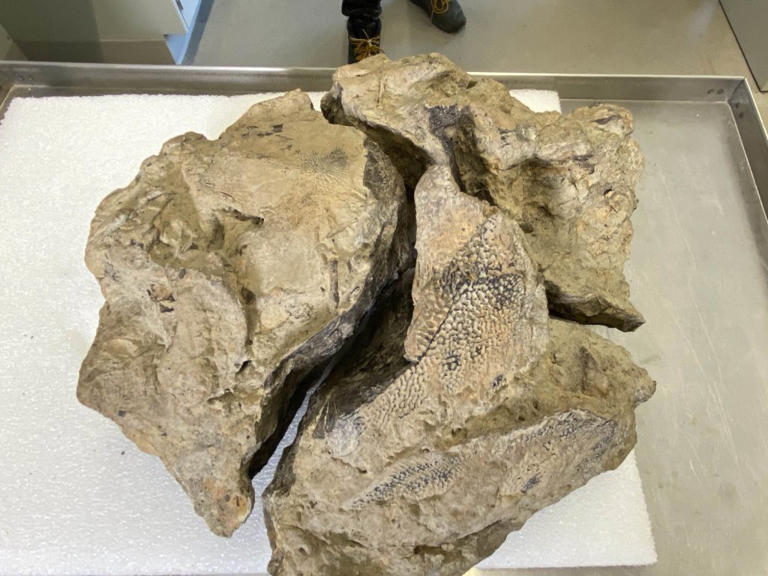

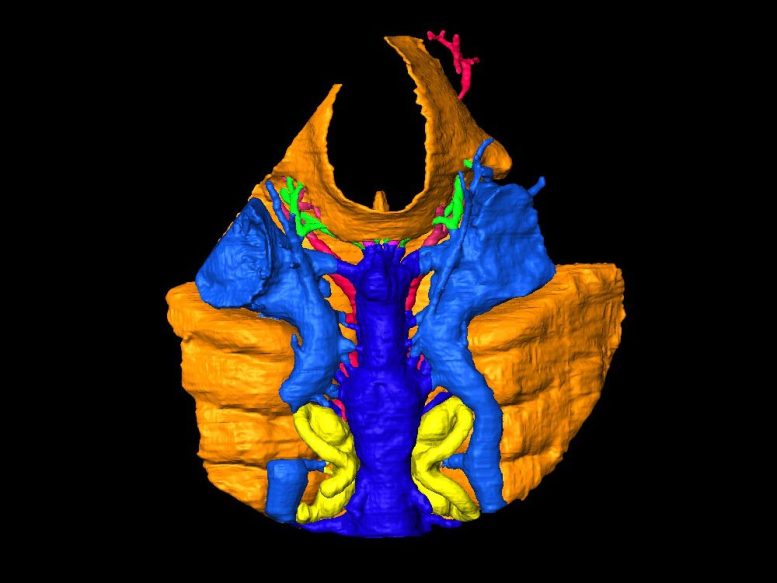

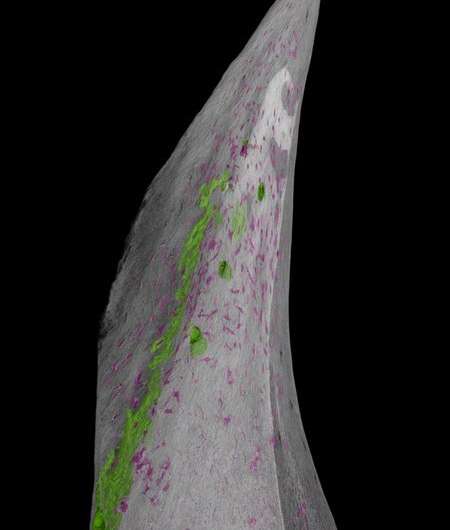

This Cerberus of the sea was a fish that stretched to 25 feet or more in length and weighed a couple of tons. It was covered in armor and had a massive skull comprised of heavy, bony plates. There were two sets of huge protrusions that looked like monster-sized fangs, and a unique pair of self-sharpening jawbones that could produce an amazing 8,000 pounds per square inch of force as this fish chomped down on its prey.

Meet Dunkleosteus terrelli, the meanest and most terrifying fish in the marine world. This part of Ohio was covered in a shallow, warm sea at the time, and Dunkleosteus snacked on the sharks of those waters, and anything else that came into its path.

"This fish is significant because it was the top predator on Earth at its time," said Amanda McGee, Head of Collections & Collections Manager of Vertebrate Paleontology at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, where the most complete displays of Dunkleosteus are displayed. "At that time, plants and insects had colonized the land, but most of life was still in the sea, and Dunkleosteus was the Tyrannosaurus rex of that period. It was the apex predator and it lived right here."

Dunkleosteus, also known by its efficient nickname Dunk, lived in the Devonian Period, the Age of Fishes. The Devonian Period was part of the Paleozoic Era in geological history and took place between roughly 420 million and 358 million years ago. With a very warm climate, sea levels were high and about 85 percent of the planet was covered in water.

"This whole area was a shallow sea, a lot warmer than it is today, and the global sea level was a lot higher, so the oceans flooded the land," McGee said. And Dunk, a ferocious marauder, ruled those widespread seas.

Paleontologists have uncovered fossil remains of other species of Dunkleosteus in distant parts of the world, McGee said, including in Morocco, Poland, and Australia, but Dunkleosteus terrelli, which occupied this part of the planet, has provided the best historical record.

When these fish died they would settle to the bottom of the vast saltwater seas, a veritable dead zone with little to no oxygen, so their remains were very well preserved. As mud and sediment covered them, these Dunkleosteus specimens were encased in a slowly developing sarcophagus.

"Over millions of years, those layers of mud turned to rock," McGee said. "And much later those rocks got scraped away by huge sheets of retreating ice in the ice age, exposing some of these fossils."

The first recorded discovery of Dunkleosteus in the region that is now Northern Ohio took place in 1867 in the shale cliffs in Lorain County. Amateur paleontologist Jay Terrell made that find and he is recognized in the scientific name of the fish, along with David Dunkle, former Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

The giant armored skull of a Dunkleosteus terrelli is on display in the Kirtland Hall of Prehistoric Life at the facility, which is located east of downtown at University Circle.

"Most of the early finds of Dunkleosteus terrelli were from people in that area," said Jayson Kowinsky, a high school physics teacher in Pittsburgh whose website fossilguy.com celebrates paleontology and fossil hunting.

"This fish is probably the world's most famous placoderm and that area of Ohio is very important in the study of Dunkleosteus. That is the world's hot spot for this fish."

Almost 100 years after Terrell's encounter with Dunkleosteus, the Ohio Department of Transportation was starting construction on Interstate 71 in the shale-rich Big Creek Valley area near Cleveland and a team of paleontologists worked alongside the ODOT crew and excavated a wide range of fossil fish and plants, including additional evidence that has assisted in the study of Dunkleosteus.

Kowinsky explained that Dunkleosteus was larger than the biggest great white sharks that swim in the oceans today, and the force of the bite produced by Dunk's shearing jaws was unmatched by even the most ferocious predators that ever have walked the earth or terrorized its oceans.

"This bite force was likely double that of a Megalodon and stronger than that of the T-rex," Kowinsky said.

Through the use of biomechanics and computer modeling, paleontologists with the Field Museum have estimated that at the tip of its fang-like structures, Dunkleosteus terrelli could exert an "incredible force of 80,000 pounds per square inch." They also marveled at the ability of Dunk to open and close its massive mouth with such speed — in just one-fiftieth of a second. This created a powerful suction-like vacuum that pulled prey into its mouth.

"The most interesting part of this work . . . . was discovering that this heavily armored fish was both fast during jaw opening and quite powerful during jaw closing," said Mark Westneat, past curator of fishes at The Field Museum, in a 2006 paper on Dunkleosteus. "This is possible due to the unique engineering design of its skull and different muscles used for opening and closing. And it made this fish into one of the first true apex predators seen in the vertebrate fossil record."

Kowinsky said that paleontologists believe that Dunkleosteus was around for about 20 million years or more, at a time when close to 99 percent of the vertebrate life on the planet was found in the seas.

"We would not be swimming in the ocean if this fish was still around today," he said.

Late in 2020, Dunkleosteus terrelli earned the official distinction as the Fossil Fish of Ohio when Senate Bill No. 123 was signed into law by Gov. Mike DeWine. Dunk joins the buckeye (state tree), cardinal (state bird), flint (state gemstone), Isotelus (state invertebrate fossil), spotted salamander (state amphibian), black racer (state reptile), and the white trillium (state wildflower).

.jpg)