FRAC SAND OVERPRODUCTION CRISIS

U.S. Silica cuts 10% of workforce as frac sand demand wanes

(Reuters) - U.S. Silica Holdings Inc said on Friday it had cut about 230 jobs, or 10% of its workforce, as demand for its frac sand comes under pressure from oil and gas producers reducing drilling in the backdrop of volatile prices.

The job cuts included employees impacted by idling of its two mines in Utica, Illinois and Tyler, Texas, the company said, adding that it expects to incur about $1.7 million in related severance costs in the fourth quarter of 2019.

Last month, U.S. Silica said it expects demand to slow down in the fourth quarter and reported a bigger-than-expected quarterly loss weighed down by lower prices.

Prices for the proppant used to crack the ground and extract oil have dropped in North America, as low oil prices and demands for higher investor returns stunted drilling activity.

The company had also forecast net sales and profits in its industrial business, which supplies sand to construction companies and glass manufacturers, to stay flat or rise marginally in 2020, hurt by trade tariffs and fears of a global slowdown.

“The difficult decisions announced today are an important element of our plan to protect margins and generate free cash flow in a.n increasingly competitive oil and gas completions market,” Chief Executive Officer Bryan Shinn said on Friday

Frac sand slump continues to sting industry

Sergio Chapa Nov. 22, 2019

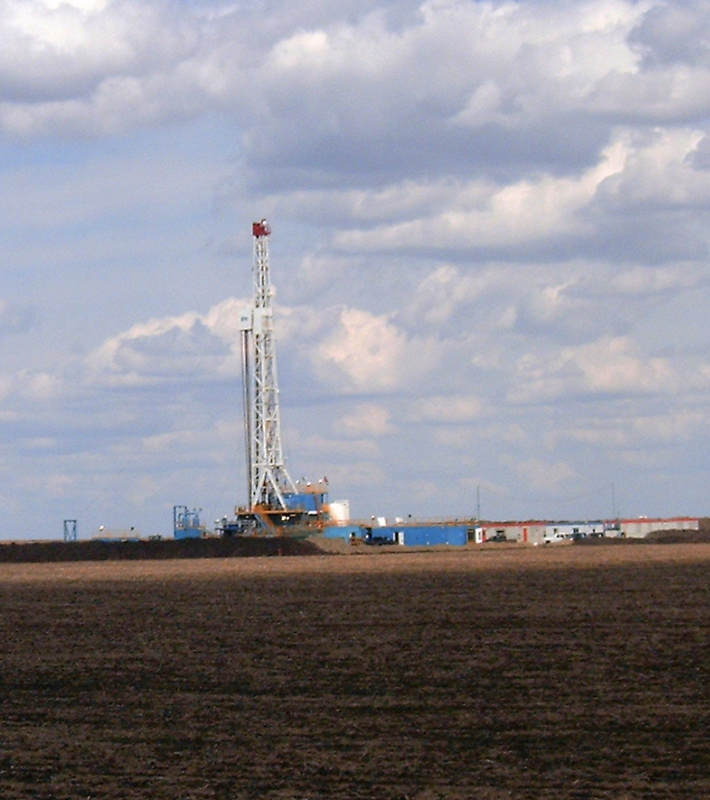

Frac sand suppliers have been hit by the slowdown in drilling activity.

Photo: Michael Ciaglo, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographer

Falling demand, abundant supplies, lower prices and and increased competition are hitting the frac sand industry as as it contends with a slowdown in the nation's shale oil and gas fields.

Katy sand products company U.S. Silica said Friday that it will idle two sand mines and cut 230 jobs, or about 10 percent of its workforce. With crude oil prices stubbornly stuck in the $50 to $60 per barrel range, many exploration and production companies are cutting back on their drilling and hydraulic fracturing operations.

Sand is a critical component of the horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing processes. It is mixed with water and chemicals and pumped into wells at high pressure to crack geological formations. The sand props open fissures that allow the oil and gas to flow into the well.

In a statement, U.S. Silica CEO Bryan Shinn said the job cuts and idled mines were difficult decisions. but necessary for the company’s survival.

"The actions taken realign our operational footprint and cost structure to more efficiently serve energy customers while simultaneously supporting the expected growth of our Industrials & Specialty Products segment,” Shinn said.

Shale Slump: Lower hydraulic fracturing activity stings frac sand business

In the early days of the shale revolution, most of the nation’s frac sand came from mines in Wisconsin and Minnesota, from where it was shipped by rail to regional depots, stored in silos and then hauled by 18-wheelers to drilling sites. Over the past three years, that business model has given way to lower mines near oil fields so sand could be hauled to drilling sites less than 100 miles away.

The crude oil price slump hit in Dec. 2018 just after several sand companies opened dozens of new mines in the Permian Basin of West Texas, the Eagle Ford Shale of South Texas and other shale plays across the United States.

Oil and gas companies have pulled more than 270 drilling rigs out of operation over the past year, pushing the U.S. rig count down by 25 percent, according to the Houston oil field services company Baker Hughes. Services companies, such as Halliburton of Houston, have cut the number of fracking crews and laid off workers.

Oil settled Friday at $57.77 in New York, down 81 cents.

During an Oct. 29 investors call, Shinn said the industry has a glut of 35 million tons of sand — driving down prices as companies compete for market share. He estimated that seven sand mines have closed and more will follow over the next several months.

As part of a plan to save $20 million a year, U.S. Silica is pairing its jobs cuts with plans to idle mines in Utica, Ill. and Tyler.. The company is reducing operations at other mines, including its Permian Basin mine in Crane County. The reductions are expected to take 7 million tons of frac sand off the market.

Following a $23 million loss on $362 million of revenue during the third quarter, the company is also looking to diversify by making a number of commercial and industrial products ranging from roofing materials to filters for blood and plasma.

Analysts say that market conditions for frac sand suppliers will get worse before they get better. James West, an analyst with the Houston investment research firm Evercore ISI, noted that U.S. Silica lowered its sand volumes guidance for the fourth quarterm expecting overall demand from the oil and natural gas industry to decline by 10 percent.

“The biggest questions everyone is trying to answer now are how much of a rebound will the industry experience when (oil and gas) budgets reset in the New Year and will it be a sharp pickup in activity or a slow grind until toward the end of the first quarter,” West wrore in a recent research note. “Slow grind is our view.”

Shares of U.S. Silica were down slightly, closing at $4.55 at the end of trading on Friday.

sergio.chapa@chron.com

Demand for Frac Sand and Concrete Drives Scarcity

By SHELLEY GOLDBERG June 25, 2019 INVESTOPEDIA

Despite appearances, we are running out of sand. While that might seem farfetched – sand is seemingly everywhere – there is not only a thriving international trade in the commodity, but it’s the second-most heavily exploited natural resource after water and, by volume, the most heavily extracted solid material in the world.

Like any commodity, sand requires uniformity. Uniform sand, or "aggregate," includes gravel, crushed stone and a number of recycled materials, such as crushed concrete, each of which has unique applications. Specialty sands also exist for industries such as golf, volleyball, sports fields, and playgrounds, as well as retail and technical services. Each has unique shape, size, hardness and color specifications.

From Playgrounds to Fracking Wells

Sand is formed by erosive processes over thousands of years and, according to a UN Environmental Program (UNEP) report, is being extracted far more quickly than it can be renewed. While the U.S. imports only about 1% of the total sand that it uses, according to the United States Geological Survey, developing countries like China and India have had to import significantly larger quantities to meet the demand created by recent construction booms. Sand's scarcity translates to price appreciation, which makes investing in sand compelling.The price of sand and gravel has increased dramatically over the last decade, from $7.06 per metric ton in 2007 to $8.80 in 2016. Specialty sands generate even higher prices: frac sand, which is used in the process of extracting oil through hydraulic fracturing, cost about $25 per tonne in 2017 but in times of short supply has climbed to $70 per tonne.

But investing in sand is challenging. Sand’s weight relative to its value makes it expensive and challenging to move and store. Investors are also unable to buy or sell futures contracts tied to sand, as they would with other commodities, such as soybeans or oil. As a result, investors interested in deepening their exposure to sand need to look to equity in companies associated with sand production.

Fueling Construction Growth

Conservative estimates place world sand consumption in excess of 40 billion tonnes a year, according to UNEP. That number is twice that of the annual amount of sediment carried by all of the rivers of the world, which means that mankind is the largest transforming agent in the world with respect to aggregates. Demand is asymmetric: Increasing demand is predominantly tied to urban growth in Asia, though it is worth noting that information on global sand consumption, particularly in emerging and frontier markets, is scarce.

Aggregate is the main constituent of both concrete and asphalt. It is also the primary foundation for building roads, parking lots and runways, homes, buildings and landscapes. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, for each metric tonne of cement used, the construction industry needs about six to seven times more tonnes of sand and gravel.

China produces over half the world’s cement, an estimated 2.41 billion metric tons (BMT) in 2017. Global cement production is expected to increase from 3.27 BMT in 2010 to 4.83 BMT in 2030.

Frac Sand Boom and Bust

Energy Exploration and Production (E&P) also consumes vast quantities of sand, mostly due to its use as a primary proppant in hydraulic fracturing. Proppants are mixed with a liquid to keep fracking wells open and facilitate the removal of oil and natural gas. For scale, individual fracking wells often use seven million pounds of sand, with some requiring up to three times as much. Wells have grown longer and wider since modern-day hydraulic fracking came about in the 1990s.

Frac sand suppliers are highly fragmented, with some 50 producers globally. In addition to energy producers themselves, frac sand suppliers were among the hardest hit by the shale oil bust beginning mid-2014, as drilling activity plummeted. Major oil and gas producers saw their market halve, but the carnage among sand suppliers was worse. With the steep decline in rig counts, sand suppliers like Emerge Energy Services (EMES) and Hi-Crush Partners (HCLP) saw their stock prices depreciate more than 90% from their 2014 highs.

But by 2016, the U.S. frac sand market heated up, even as oil prices remained depressed, due to the increasing size of wells. Producers also increased the number of fractured stages per well, which fueled a boom in the amount of sand used to drill. As U.S. crude continues to recover in price, coupled with high demand for U.S. natural gas, frac sand demand should continue to surge.

Among those producers that are publicly traded, is U.S. Silica Holdings (SLCA) the largest pure-play fracking sand provider. Fairmount Santrol Holdings (FMSA) also has a significant business line supplying for foundry, building products, water filtration, glass, and recreation markets. Hi-Crush Partners and Emerge Energy Services are structured as master limited partnerships. EOG Resources (EOG) is a large producer but uses all of the sand it mines in its own wells.

The barriers to entry for frac sand producers are high. Not only does it take time, expertise and capital to build a new mine, but it’s also difficult to time the market exactly. Furthermore, there can be supply limitations due to infrastructure or shipping constraints.

Environmental issues are also a concern. Sand extraction lowers water tables and decreases sediment supply, resulting in the destruction of ecosystems like fisheries. Sand extraction has also been linked to inland and coastal land loss, water contamination, and river embankment and coastal infrastructure damage.

Limits on Infrastructure Development

Furthermore, the planned expansion of infrastructure in many parts of the world is more ambitious than had previously been estimated. India's current $120 billion building boom making has placed sand in such high demand that illegal mining has engendered a sand mafia. Saudi Arabia, which already made headlines for importing sand despite its desert locale, announced a plan to build Neom, a $500 billion mega-city spanning 10,230 square miles.

Sand mining and dredging have been largely ignored by policymakers. But as climate change's ramifications on coastal cities become more evident, this too will likely change. Today, in the U.S., the fastest-growing use of sand includes fortifying shorelines eroded from rising sea levels and increasingly powerful ocean storms, particularly after recent powerful hurricanes. Inland uses include temporary sand dams and sandbag installations to protect residents and property from surging lakes and rivers, as well as mudslides, like those that impacted California in 2018.

While sand substitutes exist, they are expensive. Increasingly, producers have begun to turn to recycled asphalt and cement, although comparative usage is quite small.

In addition to producers, investors looking to make a play on sand could look into dredging companies and dredging/blasting equipment manufacturers, given recent advancements in robotic crushing technologies. For investors concerned about the long-term effects of a sand shortage, glassmakers (windows, glassware and cell phone screens), water filtration, septic systems, swimming pools, solar panels, and wind turbine manufacturers all rely on the material. Sand is used in the railroad industry, as well as for molds in foundries that make everything from airplane and cruise missile parts to artificial hips.

Frac Sand Mining

Hydraulic fracturing uses high pressure water to break open underground geologic formations – most commonly shale. – containing oil and gas.

Once the shale is fractured, if the fractures are not propped open, they will close again.

So frackers use frack sand to prop open the fractures to allow the oil and gas to be extracted.

They use a lot of sand:, up to 10,000 tons of sand per well.

Frack “sand” is actually tiny pieces of quartz- silicon dioxide (SiO2) also known as silica sand. It is not garden variety sand found in your kids sandbox. Because it is special, it is found in only a few places. In the United States, that currently means in the Midwest near the Great Lakes. The Southeast corner of Minnesota and neighboring Wisconsin contain vast deposits of the most desirable highly spherical sand close to the surface.

Alternatives to sand include the use of manufactured ceramic beads and even hemp. Some drillers in western Colorado’s Piceance Basin have experimented with sandless fracking in more naturally brittle formations where the broken portions of shale can themselves act as a proppant.

Overburden Removal

Before mining for frack sand, operators must remove “overburden” – topsoil or subsoil overtop the sand that is mainly composed of clay, silt, loam, or combinations of the three.

Removing the overburden requires scrapers or tracked excavators. After removal, the operator stockpiles the material in man-made earth mounds called berms. These berms can serve as light and noise barriers between the mine and nearby communities.

Excavation

After peeling away and storing the overburden, the operator then must excavate the sand. Excavation may require blasting; depending upon how tightly cemented the target silicates reside within the geological formation.

Processing

In order for the frack sand to effectively hold open the formation fissures, it must have a fairly uniform hardness and shape. To achieve this uniformity, the silicates must undergo further processing at a plant:

Washing — which involves high pressure spraying of water and dangerous chemicals on to the sand that often leaches in to the ground;

Drying — depositing the sand in to large rotating drums fed by hot air, powered by either combustion or natural gas;

Screening and sorting — sorting allows the operator to capture the sands suitable for fracking and dispose or sell the sands better suited for other purposes.

For More Information

EARTHblog Frack Sand Mining Doesn't Just Suck, It Blows

EARTHblog Where do you think the fracking sand comes from?

EARTHblog Minnesotans Declare Independence from Frac Sand Land

MPR News Wisconsin Sen. Vinehout proposes legislation to control frac sand mining

Minnesota DNR Industrial Silica Sand

Allamakee County Protectors Grassroots Iowa Group

Sandpoint Times Grassroots Minnesota Group

WBEZ Behind the fracking boom, a sand mining rush

Journal Sentinel Wisconsin attorney general levies fine against sand mining company, Dec. 16, 2013

Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism Frac sand mines credited for rising, dropping property values March 30, 2014