Archana Venkatesh,

Fri, May 17, 2024

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi is popular but divisive. Ritesh Shukla/Getty Images

The world’s largest election is currently under way in India, with more than 960 million people registered to vote over a period of six weeks. Spearheading the campaign for his Bharatiya Janata Party, incumbent Prime Minister Narendra Modi is spending that time crisscrossing the country, delivering a message he hopes will result in a landslide victory for the Hindu nationalist party.

He is a popular figure but also a divisive one. Modi’s speeches are drawing heat for their anti-Muslim rhetoric. At a campaign rally on April 21, 2024, he referred to Muslims as “infiltrators.”

He later doubled down on these remarks, suggesting that if India’s largest opposition party, the Indian National Congress, came to power, the wealth of Hindus would be snatched and given to communities that “have too many children,” a seemingly lightly veiled reference to Indian Muslims.

Such language represents a fear that Modi and the BJP have stoked many times before: that Muslims will become a numerical threat to India’s Hindu-majority population.

Modi has since claimed that he did not explicitly target Muslims in his speech, but his words – widely recorded and disseminated – have certainly been taken that way.

To some onlookers, the rhetoric is an indication that not all is well in the BJP campaign as it seeks to secure a two-thirds supermajority in Parliament. By appealing to the party’s Hindu base, the argument goes, Modi is trying to counter voter apathy in the face of high youth unemployment and rising economic inequality.

As a historian of public health in India, I believe it is important to shed light on the specific origins of anti-Muslim rhetoric and how it fits long-standing fears of Muslim population growth and the erosion of the Hindu majority in India.

Fears of a Muslim takeover

Demographic fears in India are tied to political and administrative representation and have been since the days of British colonialism.

In 1919, the British granted Indians limited franchise; Indian legislators were allowed to create policy in certain fields, such as health care and education, but not on law and order.

After the 1931 census, Indian leaders – mostly Hindus, but also some Muslims – and British officials began to express concern about the seemingly rapid rate of population growth in India, which at the time was increasing by over 1% annually.

These leaders, in common with similar efforts around the globe, began to push new birth control methods toward Indian women.

But to successfully induce large numbers of women to embrace family planning practices, colonial officials and Indian administrators had to contend with the fact that Indians of all religions were suspicious of birth control propaganda.

These suspicions stemmed from cultural practices shared by both Hindu and Muslim communities that informed women’s status in society, including child marriage, the seclusion of women and polygamy.

Policies that tried to interfere with the traditional lives of Indian women, including birth control, were widely considered harmful instances of colonial control.

Role of British colonizers

While the British used these cultural practices and suspicions to suggest that all Indians were responsible for rapid population growth and associated poverty and hunger, Hindu nationalist groups created a different narrative. These fringe groups, which emerged as a political force in the 1930s, popularized the idea that practices encouraging population growth were particularly prevalent among the Muslim population.

At the same time, there were growing tensions between the Indian National Congress party and the Muslim League, which was founded in 1906 but began to demand a separate homeland for Indian Muslims in the late 1930s.

Divisions existed in Indian society prior to British rule. By classifying Indians into categories based on caste and religion, however, British colonial rulers made these identities and divisions more rigid, pitting various communities against one another.

Communal tensions allowed the British to uphold the idea that without the control and surveillance of colonial rule, Indians were incapable of self-government and liberal democracy.

Though the British left the new nation-states of India and Pakistan in 1947, increasing Hindu-Muslim tensions after partition continued to inform family planning propaganda in independent India.

Hindu nationalists had expected the creation of a single nation with Hindu majority rule. As such, they saw the creation of Pakistan – a homeland and nation-state for South Asian Muslims – as a massive failure of the Indian freedom movement and a loss for India.

Additionally, post-partition leadership and administrators in India were for the most part drawn from Hindu men and some women, since the majority of educated and elite Muslim classes ended up in Pakistan.

As a result, colonial-era perceptions of Muslims continued to inform the way Indian policymakers and administrators created and implemented health care and education policy. In particular, preexisting perceptions of Muslim hyperfertility in Indian policymakers’ minds became more deeply entrenched with partition.

Population control programs

As India launched its first major population control program in 1951, administrators at all levels of governance assumed that uptake of birth control would be lower in Muslim communities than Hindu communities.

In actuality, the factors that influenced the rate of uptake of IUDs, oral contraceptives and tubectomies in postindependence India were governed more by geography – whether women lived in rural or urban areas, and were from the country’s north or south – and class status.

Since 1951, population control has been one of the major goals of Indian policymaking as part of a program to reduce poverty and improve public health. But the continued assumption that Indian Muslims are unwilling to participate in population control practices has led to the public perception of Islam as “superstitious” or “backward.”

Research has shown that Indian Muslim communities across the nation have felt the effects of this stereotyping, especially in northern India. Muslims reported being disproportionately targeted by population control initiatives. These concerns among the Muslim community intensified with the aggressive forced sterilization program carried out by the Indian state under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in the 1970s.

Using religion for politics

Modi’s party, the BJP, was formed in 1980 but failed to win significant elections until the 1990s.

Several people on top of the 16th century Babri Mosque five hours before the structure was completely demolished in December 1992. Douglas E. Curran/AFP via Getty Images

The main focus of their organizing in the 1980s and 1990s was to demand the demolition of a mosque commissioned by Mughal emperor Babur in Ayodhya, traditionally regarded as the birthplace of Hindu deity Rama.

In tandem with this campaign, the BJP promoted fears of Muslim demographic dominance in India, tying demands for “taking back” the land on which the Babri Masjid was built with fears of a Muslim majority.

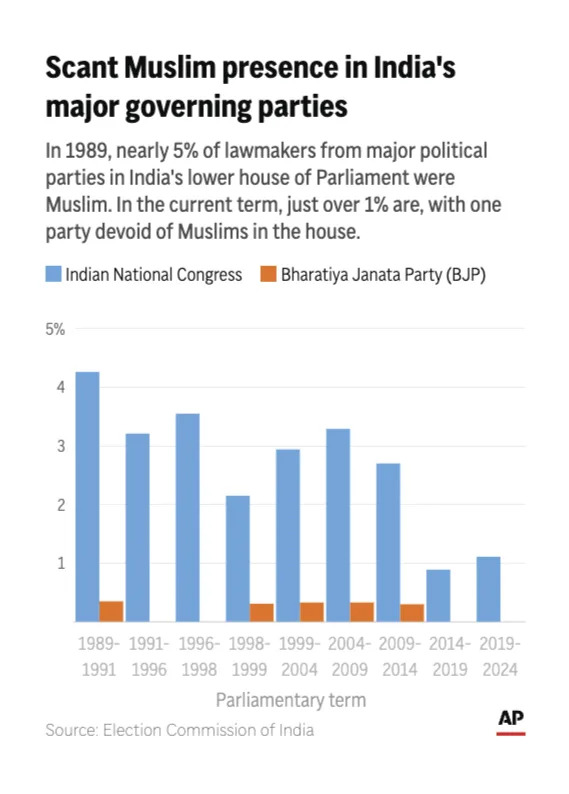

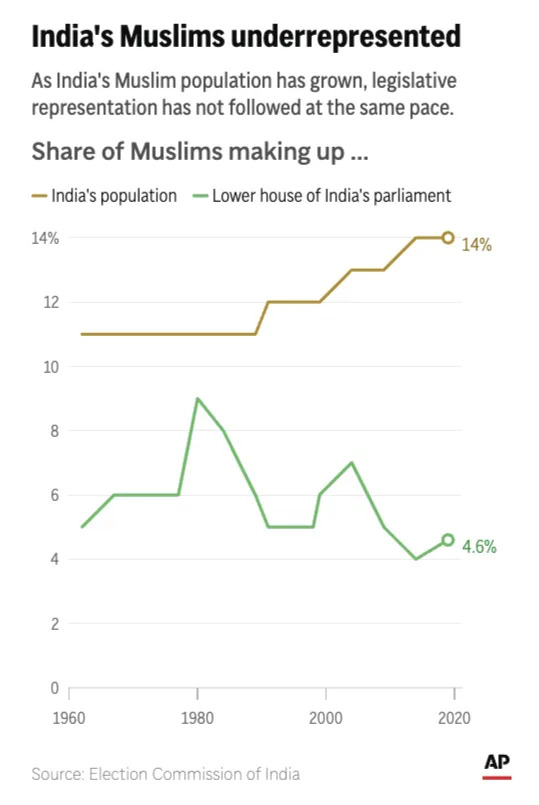

But such fears are unfounded. Despite the Muslim minority growing from 11% in the mid-1980s to 14% today, their representation in Parliament has actually declined, from 9% in the mid-1980s to 5% today.

Since the BJP came to power in India in 2014, party leaders have relied on the historic fears of imagined Muslim population growth to help them win successive elections at the state and national level and pass legislation such as the Citizenship Amendment Act, which discriminates against Muslims. BJP leaders have accused Muslim men of forcibly converting Hindu women to Islam through “love jihad,” a conspiracy theory that Muslim men deceptively seduce Hindu women to increase their demographic strength.

Modi’s latest statement referring to “those who have too many children” is the latest iteration of a long history of Hindu demographic fears – and has proven to be a lasting one.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Archana Venkatesh, Clemson University