Iran's missile and drone attacks on Israel largely failed, with many intercepted or malfunctioning.

Around 60 of Iran's missiles failed on their own, multiple reports say.

Iran appears to remain confident about possible future conflict with Israel.

Half of the missiles Iran fired at Israel over the weekend failed on launch or malfunctioned and crashed, according to reports.

More than 300 missiles and drones were fired toward Israel from Iran on Saturday evening in retaliation for an airstrike on the country's consulate in Syria.

Around 99% of the missiles launched were intercepted by Israel, the US, the UK, France, and Jordan.

Iran had warned for weeks that the attack was coming. That gave Israel's allies time to prepare — and avoided targeting civilian locations.

Israel praised the defense effort as a "significant strategic achievement." But around 60 of Iran's missiles failed on their own, according to several reports.

An estimated 50% of Iran's 120 ballistic missiles failed to launch or crashed in flight, unnamed US officials told CBS News and The Wall Street Journal.

Israeli Ambassador to the UN Gilad Erdan shows a video of drones and missiles heading toward Israel during a United Nations Security Council on April 14, 2024.CHARLY TRIBALLEAU via Getty Images

The attack also consisted of 170 unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and 30 cruise missiles, none of which crossed into Israeli territory, according to an online statement shared by a spokesperson for Israel Defense Forces (IDF).

Speaking to CBS News, two US officials said five ballistic missiles made it through air defenses and impacted Israeli territory.

Four landed at Navatim Air Force Base, which was thought to be Iran's primary target. One hit a runway, one hit an empty hanger, and another hit a hanger that wasn't in use, the publication said. Meanwhile, another missile appeared to be aimed at a radar site in northern Israel but missed, the outlet added.

At the time of writing on Monday, one person — an unnamed 10-year-old girl — was reported as "severely injured" by shrapnel, the IDF confirmed. The details of her condition have not been released.

Though Israel has not yet said how it plans to respond, the IDF spokesperson said it is "prepared and ready for further developments and threats."

"We are doing and will do everything necessary to protect the security of the civilians of the State of Israel," they added.

Amir Saeid Iravani, Iran's ambassador to the UN, told Sky News that reports of Israel's forthcoming response are a "threat" and "talk, not an action."

He said Israel "would know what our second retaliation would be" and that they "understand the next one will be most decisive."

Iran ignored warnings from the US before it launched its attack. President Biden said on Friday that he expected Iran to attack Israel "sooner, rather than later." His message to Iran was short and simple: "Don't."

Sean McFate, a national security and foreign policy expert at Syracuse University, previously told BI that the Biden administration is losing its authority as its military support for Israel and simultaneous humanitarian aid for Gaza is sending mixed messages.

"The fact that the Biden administration is both arming Israel and sending aid to Gaza shows the world that the Biden team has no strategic competence," McFate said. "They've already lost control."

Representatives for the IDF, Iran's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the US Department of Defense did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Business Insider

Iran’s Better, Stealthier Drones Are Remaking Global Warfare

Peter Waldman

Mon, Apr 8, 2024

(Bloomberg) — In January, rebels fighting the Sudanese army shot down a drone near Khartoum. As jubilant gunmen posted video of the wreckage on social media, they offered a fresh data point on how Iranian technology is remaking the global weapons trade.

The drone in the video, which is clearly modeled after Iran’s Ababil model — the workhorse of paramilitaries across the Middle East since it was developed in the 1990s — reflected a design tweak: Its two front tires, instead of the usual one, provided actual battlefield evidence that Sudan is modifying the Iranian drone into its own weapon, which it calls the Zagel-3.

That revelation follows the emergence in the last two years of ramped-up Iranian drone production in at least five other countries, from South America to Central Asia. Most recently, Russia has started making Iranian drones for its war in Ukraine, bringing the number of countries using Iranian technology, assistance, or parts to at least a dozen.

Iran’s mastery of relatively low-tech drone warfare poses urgent new risks to Middle East stability; its leaders threatened last week to retaliate against Israel for an airstrike on its embassy in Syria that killed officers of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. Earlier this year, three American service members were killed and more than 40 others injured by an Iranian-designed kamikaze drone at the Tower 22 US military base in Jordan. Farther afield, Tehran’s growing role in proliferating the disruptive technology to militias and militaries near and far has been roiling regional animosities on four continents.

Iran’s drone diplomacy is earning foreign currency to fund its defense industry, strengthening its strategic alliances, and making it a formidable arms dealer — with the potential to change the nature of conflict around the world.

Shackled by more than 40 years of economic sanctions, Iran is busting out on the wings of what are essentially model airplanes that are propelled by lawnmower motors, guided by US-made components plucked from the internet and retailers’ shelves and weaponized for war. More than its missile program, its reputed terrorist network, or even what the US and the International Atomic Energy Agency have described as Iran’s past nuclear-weapons efforts, drones are making the Islamic Republic a player with increasingly far-flung ambitions. The US and allies such as Israel are struggling to respond, particularly in the febrile crescent that extends from Iraq through Syria and into Lebanon, Jordan, Gaza, and Yemen.

“The last two years have been a period of hyper-acceleration of new tactics and techniques for Iran’s employment of UAVs,” or unmanned aerial vehicles, says Matthew McInnis, a Pentagon intelligence officer for 15 years and, from 2019 to 2021, the State Department’s deputy special representative for Iran. “All states are behind in terms of figuring out defensive capacity.”

For its part — and despite a recent leak of hacked documents that indicates otherwise — Iran has repeatedly denied selling Russia drones for use in Ukraine but admitted it sent a “small number” before the February 2022 invasion. Foreign Minister Hossein Amirabdollahian said in January that Iran wasn’t responsible for other countries copying Iranian drones. And in a statement to Bloomberg News, Iran’s permanent mission to the United Nations said, “from a moral standpoint, Iran abstains from engaging in arms transactions with any party embroiled in active conflicts with another due to concerns regarding the potential utilization of such weaponry during the course of said conflict.”

Iran’s drones are getting better and stealthier. The one that hit Tower 22 in January penetrated US defenses by shadowing an American drone that was landing there — meaning some defenses may have been down — according to two members of the Syrian conflict-monitoring group, ETANA Syria. The group tracks and analyzes data from a reputable network of military and civilian contacts in the Middle East, says Joel Rayburn, a long-time US Army intelligence officer who, from 2017 to 2021, served as a senior official for the Middle East at the US National Security Council and the State Department. “The data they gather enables them to see emerging trends in the security situation often before they are apparent.”

A spokesman for the US Department of Defense called Iran’s procurement, development, and proliferation of drones “an increasing threat to international peace and security” and noted that Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin last month established a panel of senior leaders to find effective ways to address “this urgent operational challenge.” Yet the Pentagon has released little information about the attack in Jordan.

The Washington Post cited a defense source saying it was a Shahed-101, a small attack drone that needs no special equipment for launch, flies low to better evade radar, and can travel at least 700 kilometers (435 miles), three times the range of the Ababil-2 — the previous mainstay of regional militias. The Shahed-101 made at least two other successful strikes against US forces in January, breaking through American defenses before Iran said it was pulling back its proxies to ease tensions.

Iran is believed to have adapted the shadowing maneuver, an old trick with piloted aircraft but new for drones, from Russia’s experience in Ukraine. Iranian analysts have traveled to Russia to study the success of the Iranian Shahed-136 drones manufactured there by the thousands for use against Ukraine and to further refine their evasion tactics, says Nikita Smagin, an Iran expert at the Russian International Affairs Council in Moscow.

“Russia and Iran are learning from each other. That is almost as important as the technology-sharing itself,” says McInnis, the former US envoy and intelligence officer.

In the Red Sea, Yemen’s Iranian-sponsored Houthis have managed to slash trade through the Suez Canal by more than 50% this year by firing drones and missiles at cargo ships. And since the October outbreak of war in Gaza, Iranian-backed militia groups in Syria and Iraq have bombarded remote US military bases in the region dozens of times, including the fatal January strike.

Iran’s drone use grew more sophisticated after the Trump administration pulled out of the Iran nuclear agreement in 2018. US and European diplomats negotiated for two more years to extend related United Nations Security Council restrictions on Iranian missile and drone sales. But after the US killing of Iranian Maj. Gen. Qasem Soleimani in a drone strike in Baghdad in January 2020, Iran and its backer Russia were unlikely to accept any further UN limits on Iran’s weapons programs, concluded McInnis, who led the talks with European allies. The negotiations collapsed. “Basically after that the Iranians were waiting for the US election, and then COVID hit,” making talks difficult, he says.

The UN restrictions on Iran expired in October, days after war engulfed Gaza. A few weeks later, the IRGC unveiled its most sophisticated weapons and drones to date for Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, at its aerospace museum in Tehran. They included drones such as the latest Shahed-139, an improved version of the medium-altitude, long-range Shahed-129 deployed in Syria, and the high-altitude, long-range Shahed-147 spy drone, comparable to Northrop Grumman’s Global Hawk.

The ayatollah himself was photographed next to a Shahed-149 “Gaza” drone, with a battery of missiles underwing — named and designed to send an unmistakable message. The attack drone boasts a throw weight exceeding three tons, a payload of 13 bombs, and a range extending up to 2,500 km — far enough to reach Israel.

A model of the unmanned Gaza was also featured at Iran’s pavilion at Qatar’s annual maritime defense show in Doha last month. On March 13, Iran’s defense minister announced Iran is now self-sufficient in the production of drone engines and disclosed that its overall arms exports had increased four to five times over the past two years, according to the official Islamic Republic News Agency.

Sanctions are the mother of invention — and circumvention. Blocked by export controls from purchasing Western technology with possible military applications, Iran relies on whatever electronic parts it can buy from Asian suppliers or can spirit from the US and Europe through a wide network of front companies.

The gleanings of this scavenger-style approach power Iran’s most lethal suicide drone, the Shahed-136, which is turning up in barrages on Ukrainian battlefields. Almost every part is of American or European origin, according to an analysis of drone wreckage by Ukraine’s Independent Anti-Corruption Commission. For example, the Shahed-136 uses a communications chip made by Wilmington, Massachusetts-based Analog Devices Inc. that’s for sale online from a UK-based electronics distributor’s website in Hong Kong for HK$2,649 ($339) and available in 11 other Asian countries. The same drone uses a Dallas-based Texas Instruments Inc. microcontroller listed for HK$290.

A spokesperson for Texas Instruments said the company abides by all US export restrictions and requires its distributors to as well, carries out multiple screenings on customer orders, and takes action if it learns of illicit diversions. An Analog Devices spokesperson said it adheres to all sanctions and embargoes on Iran and maintains “stringent monitoring and audit processes” to prevent illicit diversions of its products by resellers. Some lawmakers are incredulous.

US companies either “know or should know where their components are going,” said Democratic Senator Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut, during a February hearing on US export controls. He called the continued flow of US technology to Russia, which turns up in Iranian drones and Russian missiles on the Ukrainian battlefield despite export restrictions, “emblematic of a larger failing with huge national security implications for the United States.”

The origin of Iran’s drone industry is a story of innovate or die. The revolutionary regime has faced US and international sanctions off and on since militants stormed the American embassy in Tehran in 1979. Self-sufficiency is a way of life.

Iran’s first homemade drones anchored its arsenal during its long standoff against Iraq in the 1980s, as the US and Saudi Arabia lavished weapons and money on Saddam Hussein. A quarter-million Iranians died. At the time, Western military planners were still debating the ethical and battlefield implications of drones. Iran never wavered. A drone-development ecosystem of universities, private companies, and military research centers emerged.

In the early 2000s, Iran shared much of its drone technology with Syria, its closest Middle East ally, according to an unpublished report by ETANA, which closely tracks military actions in the region. Dozens of Iranian scientists moved to Aleppo in northern Syria to work in the country’s main weapons lab and co-developed four suicide drone models with their Syrian counterparts. The team even converted two fixed-wing aircraft — the MIG-21 and a small, reverse-engineered Cessna — into pilotless kamikaze planes that were deployed against insurgents during Syria’s civil war.

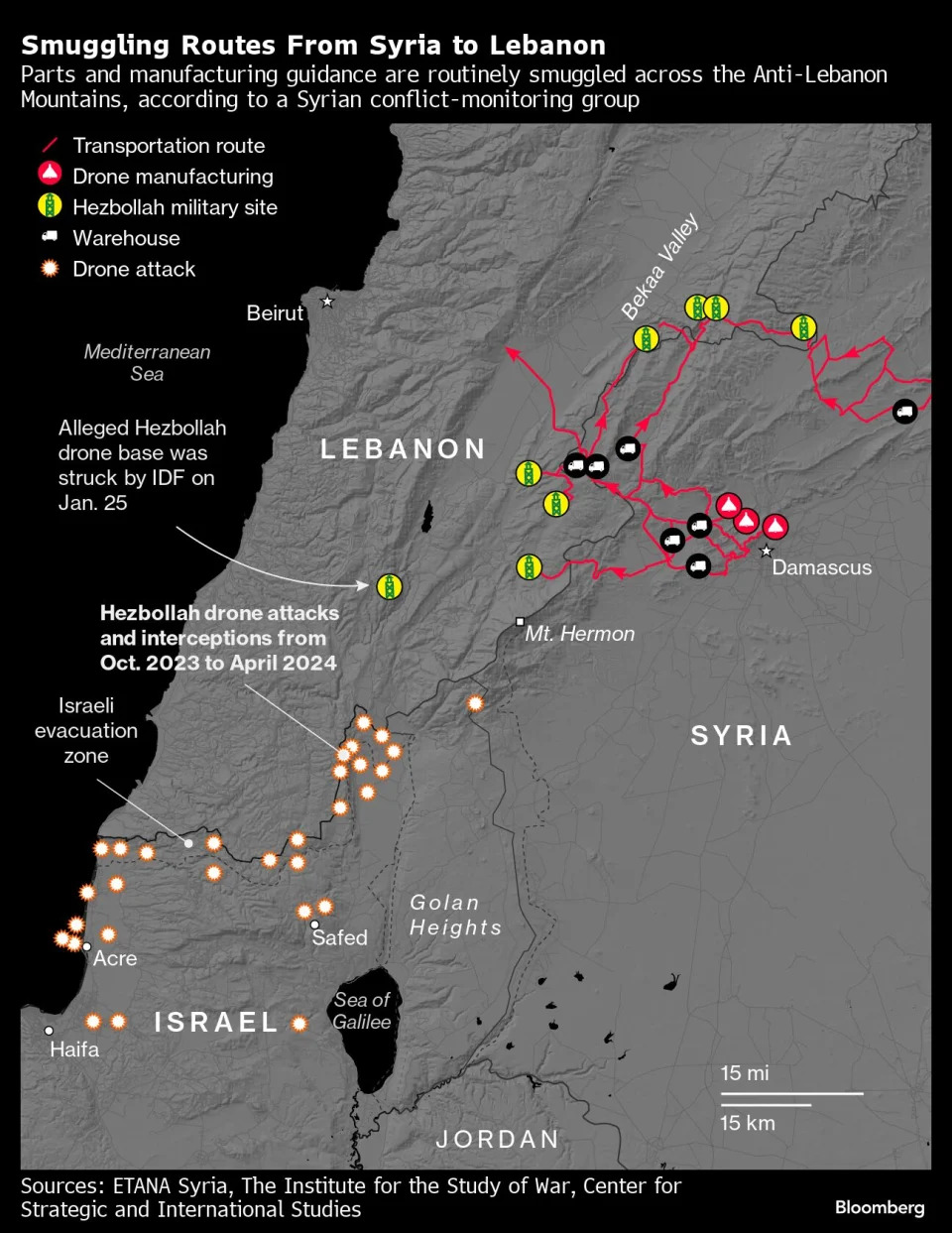

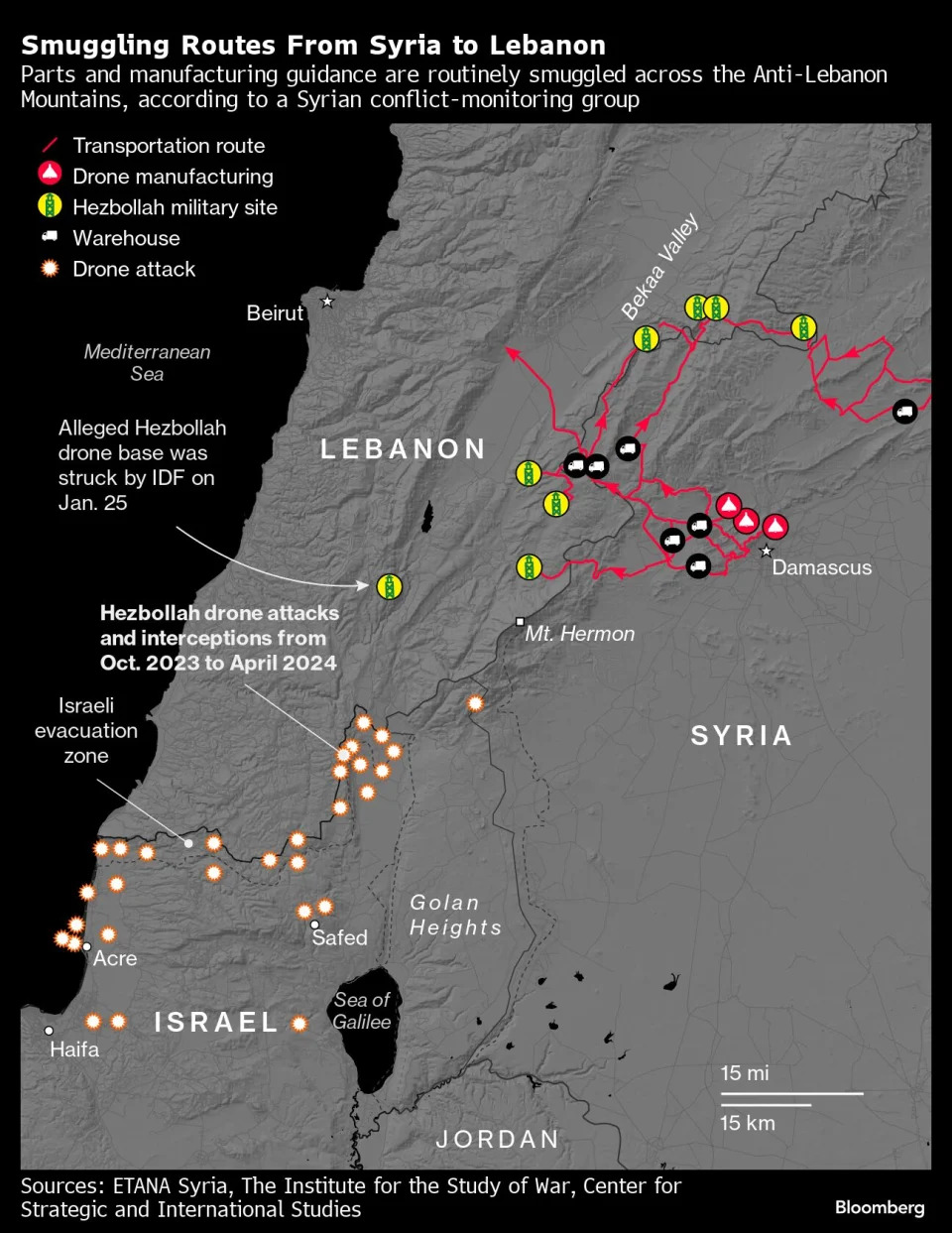

Parts and manufacturing guidance are routinely smuggled from Syria to the Hezbollah militia in Lebanon, which produces a range of drones for battling Israel, according to the ETANA report. In 2010, Iran agreed to cover all costs of co-produced drones and parts delivered to Hezbollah, the report says. One joint-venture model, the Ababil-3DI surveillance drone, was fabricated in Lebanon using equipment made by Samsung and Hyundai and used a device made by ATEN International Co. in Taiwan to transmit high-resolution images to Hezbollah’s ground stations, according to ETANA’s report. In 2022, ATEN announced it stopped all exports to Iran. Both Samsung and Hyundai have dozens of subsidiaries, and it’s unclear which units the ETANA report refers to. Representatives declined to comment.

Iran’s own drone technology got a lift in 2011, when the nation’s cyber command electronically hijacked a Lockheed Martin RQ-170 Sentinel operating on the Afghan-Iran border. Iranian aerospace experts reverse-engineered the fiberglass, bat-shaped drone, and placed it in a plexiglass case at a Revolutionary Guard base for guests to admire, according to a Syrian military engineer who later saw it. In 2018, a clone of the US drone, laden with explosives, made its debut flying from Syria into Israel during a particularly tense moment in the Middle East. Israeli helicopters shot it down.

“Can you imagine if an Iranian drone exploded in Tel Aviv? It would have prompted a war,” says Rayburn, the Iran expert who was on the NSC staff in the White House at the time. “That was six years ago and led directly to what the Iranians are deploying now across the region.”

Today in Iran, foreign front networks managed by thousands of private companies provide imported parts and sometimes finished components to state drone manufacturers. Descriptions of these back-channel supply chains have emerged in at least half a dozen US indictments filed or unsealed since 2020, which allege that Iranians attempted to launder US-made parts orders for drones and other weapons through businesses in China, the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, and Europe.

One US case involves Jalal Rohollahnejad, 46, whose tribulations show how some of Iran’s brightest computer scientists and engineers spend much of their time dodging sanctions. The defense and oil industries are among the few sectors of Iran’s sanctioned economy with job prospects for engineers, who comprise about 40% of Iran’s total unemployed population of 2.5 million.

After graduating from college in 2002, Rohollahnejad worked for Iran’s Aerospace Industries Organization “on research projects that were 100% scientific,” he would later tell a French judge at his extradition hearing. The AIO, which manages Iran’s missile program, was designated for sanctions by the US in 2005 and the European Union two years later. Rohollahnejad earned his PhD in optical engineering at Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan, China, where, from 2014 to 2017, he co-authored 15 research papers about optical sensors in scientific journals. He worked for a Chinese company called Wuhan IRCEN Technology, which the US Commerce Department alleges supplied optoelectronic parts to Iran’s aerospace industry.Rohollahnejad, who responded in writing to questions from Bloomberg over LinkedIn, says he worked for Wuhan IRCEN to earn money for graduate school, but didn’t export any optoelectronic parts or US-made goods to Iran and abided by all Chinese and Iranian laws.

He later joined a private defense contractor in Tehran, which the US Treasury sanctioned in 2017 for supplying electronic parts to the Revolutionary Guards’ drone program — the sort of internal supplier that Iran cultivates to reduce reliance on foreign suppliers. “They’ve learned they can’t rely on anyone else,” says John Krzyzaniak, a Farsi-speaking researcher at the Wisconsin Project on Nuclear Arms Control in Washington.

In 2019, Rohollahnejad was arrested on a US Interpol warrant at the Nice airport and jailed in France pending extradition to the US to face charges of procuring restricted technology for Iran. After being held for 13 months, Rohollahnejad was swapped for a French researcher imprisoned in Iran, a decision the US sharply criticized. Rohollahnejad says he traveled to Nice at the request of an Iranian official to review some oceanographic research by the French company, Marine Tech SAS. “There is a mistake,” he says.

One of his alleged accomplices in the procurement scheme, Saber Fakih, 48, was arrested in the UK and extradited to the US, where he pleaded guilty to sanctions violations in 2022 and was sentenced to 18 months in prison. In Fakih’s confession statement in US District Court for the District of Columbia, he outlined a ruse led by Rohollahnejad and another indicted Iranian national to export to Iran a military-grade industrial microwave system from Massachusetts and a counter-drone electronic-warfare system from Maryland.

Rohollahnejad denies the US charges and says he didn’t know the microwave device had any military use. He says he was acting as a middleman for an Iranian food company that wanted to purchase the machine for food preservation. He declined to comment on the counter-drone system, which he says he didn’t personally order.

As the purchases were falling apart, Rohollahnejad emailed Fakih to reassure him he’d be taken care of. “We can start some other business in oil and gas field to cover some penalties of the microwave oven project,” Rohollahnejad wrote, according to Fakih’s confession. “I have some relations in Iran government [who] can support us.” Rohollahnejad says he wrote the emails only because he felt obligated to get the Iranian food company’s money back.

He’s proud of Iran’s engineering accomplishments with drones and other technologies, while uneasy about their use. “Most of us don’t like to use weapons in any invasion, especially by Russia in Ukraine,” Rohollahnejad says. “Iranian people do not have a good memory of the Russian Empire, the Soviets, and also the new Russia. They do not adhere to any ethics with their neighbors.”

Noisy, slow, and hardly discreet, drones are typically shot down at a cost far higher than the price of a typical Shahed or Ababil model. In Ukraine, volunteer drone-hunting teams track and fell them from the skies with hand-held floodlights, laser pointers and high-caliber machine guns. Yet in the Red Sea, the US and its allies are using anti-aircraft missiles, such as the Sparrow, the SM-2, and the Sea Viper, which can cost as much as $1 million apiece. “States are using inordinately expensive assets to shoot down cheap things,” says Erik Lin-Greenberg, an historian of military technology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who researches the dynamics of drone warfare.

The Pentagon “is actively working to develop and deliver effective and affordable counter-drone capabilities,” spokesman Tom Crosson said in emailed responses to questions for this story. Neutralizing sophisticated drones isn’t easy, he said. “Depending on the size, maneuverability, speed, and other on-board technical capabilities of the drones, mitigating them requires a layered and integrated air defense architecture.”

Drones’ value proposition encourages users to unleash fusillades in hopes one or two hit their target. Russia has launched wave after wave of Iranian kamikaze drones at Ukrainian energy facilities and urban centers in recent months. On March 6, for example, it launched 42. While Ukraine’s air force said 38 were shot down, four slipped through and damaged several buildings, wounding at least seven people and knocking out power to 14,000 homes. The World Bank estimates Russia’s attacks have caused roughly $12 billion of damage to Ukraine’s energy sector.

By helping allies and proxies produce drones on their own turf — a unique approach in the drone industry — Iran’s partners gain technology and jobs, while Iran maintains a measure of deniability for how the weapons are used. Hacked documents recently leaked by the Prana Network show Russia is paying Iran $1.16 billion to manufacture 6,000 high-end Shahed-136 kamikaze drones through 2025. Striking video released in Russian media in March shows line after line of the triangle-shaped weapons that the IRGC says are capable of carrying 50 kilograms of explosives 2,500 km.

They’re being built at an industrial park in Alabuga, Tatarstan, about 1,000 km east of Moscow, where 3M Corp. and Ford Motor Co. had manufacturing ventures until the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The withdrawal of Western foreign investment left thousands of engineers free to turn their skills to weapons production. Much of the payment to Iran is expected to come in Russian arms, such as advanced Su-35 fighter jets.

To supporters of Iran’s clerical regime, its ability to produce such a valuable weapon for Russia — “the game-changer in Ukraine” — vindicates Ayatollah Khamenei’s stubborn insistence over the years that Western sanctions only make Iran stronger, says Vali Nasr, an Iran and Afghanistan adviser in the Obama administration and professor and former dean at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. “Khamenei said what did Russia and China gain after all those years working with the West, only to be slapped down,” Nasr says. “He sees the US as incorrigible imperialists.”

Some drone deals are more adventurous than others. Iran recently reestablished relations with Sudan after a seven-year rift, to help the army fight a Sudanese paramilitary group called the Rapid Support Forces. Experts say the insurgents are supported by Iran’s rival across the Persian Gulf, the UAE, though UAE officials have denied that. Sudan’s armed forces said in March 2022 that they had produced the Zagel-3, the apparently modified Ababil with two wheels.

Elsewhere in Africa, Ethiopia has also used Iranian drones to quell rebellions on two fronts. And in Tajikistan, a cooperative US ally on a range of Central Asian issues, Iran’s drone production is causing a quandary in Washington over whether to sanction the government for collaborating with Iran’s IRGC. Such international manufacturing potentially gives Iran opportunities to skirt sanctions and obtain components in a country not subject to US export controls on technology, and then to use the foreign plant as a manufacturing base to re-import the final product, says MIT’s Lin-Greenberg.

Meanwhile, Morocco is angry at Iran for sending drones to Algeria for Polisario Front separatists in Western Sahara. Venezuela, which has been making Iranian drones since 2007 and is believed to have recently upgraded to include suicide drones like those being deployed in Ukraine and the Red Sea, could potentially threaten its neighbor and rival, Guyana. And Bolivia’s request for drones from Iran to monitor its border and combat drug traffickers has sparked a diplomatic spat with Argentina.

“Iran wants to be taken seriously as a world power, so they find nooks and crannies that give them a perch,” Nasr says.

In the end, unless China is willing to crack down on technology sales to Iran, stifling Iran’s drone industry is a lost cause, says Don Pearce, a former chief of interdiction at the Commerce Department. It may take five to 10 years for the West to develop effective military means to counter Iranian drones, experts say.

“It’s like sticking your finger into a levee that’s collapsing. The best we can do is try to slow it down and make it more expensive for Iran, which we’ve succeeded in doing,” Pearce says. “Trying to control them is like trying to control the jet stream from bringing air particles to Iran.”—With assistance from Noah Buhayar, Vlad Savov, Ethan Bronner, David Kocieniewski, Daniel Flatley, Patrick Sykes, Mohamed Alamin, Heejin Kim and Yoolim Lee.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek