ERASING THE BINARY OPPOSITIONS

THE POSITION OF WOMEN CHARACTERS

IN ISHMAEL REED’S JAPANESE BY SPRING

Jiří Šalamoun

—Theory and Practice in English Studies, Vol. V, Issue 1, 2012—

https://is.muni.cz/repo/1105754/THEPES_Vol_V_issue_1_article_1_Salamoun.pdf

I. Introduction

The Raven myths of the Pacific Northwest are comic,

but they deal with serious subjects: the creation of the

world and the origin of Death. The major toast of the

Afro-American tradition, “The Signifying Monkey,” is

comic, but it makes a serious point: how the weak are

capable of overcoming the strong through wit.

The calypso songs of Trinidad may be comic, but they deal

with serious subjects [...] My work is also comic, but it

makes, I feel, serious points about politics, culture, and

religion. (Ishmael Reed 1988: 140)

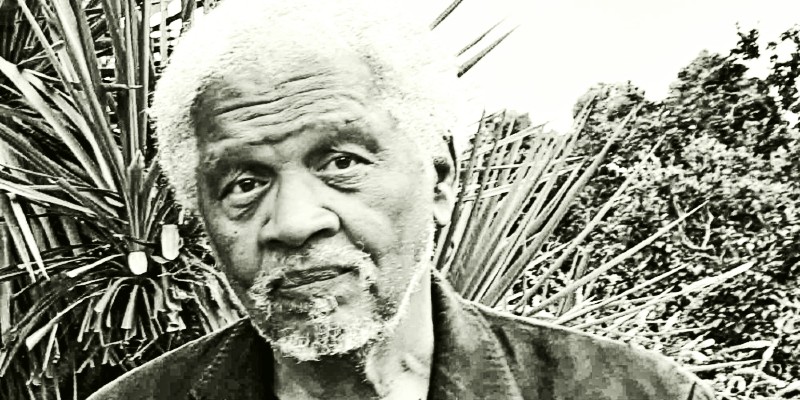

ALTHOUGH Ishmael Reed is the author of nine novels, six collections of poetry, and nine collections of essays, not many readers know what to expect when they happen to

hear his name. However, the title of Reed’s third book of essays, Writing Is Fighting: Thirty-seven Years of Boxing on Paper, combined with the passage quoted above, should give

one a succinct image of Reed’s style, writing technique, and approaches adopted in writing.

All of Reed’s novelistic endeavours can be encapsulated in the following plot line: a much weaker individual challenges an oppressive force which negatively influences the lives

of many other individuals, the proverbial Others. Through the continuing struggle of the individual, the prime position of this oppressive force is deconstructed, and its power wanes until it ceases to threaten those Others.

Throughout his prolific writing career, Reed has taken on many heavy-weight opponents; and, thus, Afro-centrism, white racism, the European paradigm of the Enlightenment,

and the Western literary canon have all been deconstructed in his literary boxing-ring. Since Reed is very careful not just to switch the binary opposition of the Oppressor/Oppressed

equation, but also to erase, as best he can, instances of such a

system (Hogue 2009: 145), his works have been lauded as a key example of postmodern, multicultural writing. But Reed’s later work has been doubted by many who have been

concerned with the position of men and women in his novels.

Since some critics have pointed out the unbalanced position of men and women in his oeuvre (Hume 1993: 511; Womack 2001: 237), this article will examine the position of

women and men in Reed’s latest novel, Japanese by Spring, in order to discover whether it is aligned with Reed’s attempts to erase binary oppositions or not. It will argue that, while

the position of women in Reed’s early fiction is not in alignment with his attempts to deconstruct binary oppositions, this situation changes dramatically in Japanese by Spring,

where women hold better positions than men.

It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Showing posts sorted by relevance for query ISHMAEL REED. Sort by date Show all posts

Showing posts sorted by relevance for query ISHMAEL REED. Sort by date Show all posts

Thursday, May 14, 2020

Mumbo Jumbo

By Alan Friedman

Aug. 6, 1972

Credit...The New York Times Archives

See the article in its original context from

August 6, 1972, Section BR, Page 1

https://www.nytimes.com/1972/08/06/archives/mumbo-jumbo-by-ishmael-reed-illustrated-223-pp-new-york-doubleday.html

https://www.nytimes.com/1972/08/06/archives/mumbo-jumbo-by-ishmael-reed-illustrated-223-pp-new-york-doubleday.html

“The Norton Anthology of Poetry” spans the centuries from Chaucer to Reed. Whether he likes it or not, Ishmael Reed has for some time now occupied a black outpost in a white landscape. To judge from his new book, he doesn't like it much. His latest work, written with black humor, is a satire on the unfinished race between the races in America and throughout history. It is a book of deliberate unruliness and sophisticated incongruity, a dazzling maze of black‐and‐white history and fantasy, in‐jokes and outrage, erudition and superstition. Not only to white readers like myself wilt the way into and out of this maze be puzzling. For though it's a novel, the author's method is not novelistic. Wholly original, his book is an

unholy cross between the craft of fiction and witchcraft.

I don't mean merely that “Mumbo Jumbo” is about such mysteries as HooDoo or VooDoo. “Black Herman walks to the bed, picks up her scarf, and casts it to the floor where it becomes a snake.” I mean that it attempts, through its deadpan phan tasmagoria of a plot, and through the black art of the Magus as storyteller, to achieve the kind of hold on the reader's mind that from ancient times and in primitive contexts has always been associated with the secret Word, the sacred Text.

The plot of “Mumbo Jumbo” is mind ‐ boggling. In the 1920's an epidemic called Jes Grew begins to infect the United States, especially its black citizens. Topsy said he “jes' grew,” but Reed traces the origins of the Jes Grew infection back to the Egyptian god Osiris. As the plague spreads in the 1920's, a worldwide conspiracy, the “Mu'tafikah(?),” be gins to seize African, Oriental, and native American art treasures from white museums “of Art De tention” in order to return them to the peoples who created them. Locked in deadly combat with this “Black Tide of Mud” are “an ancient society known as the Atonist Path” (Aton, the Sun God), “its military arm the Wallflower Order,” and the medieval Knights Templars. As someone in the book notices, “It has been an interesting 2000 years.”

But just what is this potent infection the author calls Jes Grew? “Ask Louis Armstrong, Bessie Smith, your poets, your painters, ask them how to catch it. Ask those people who be shaking their tambourines impervious of the ridicule they receive from Black and White Atonists, Europe the ghost rattling its chains down the deserted halls of their brains. Ask those little colored urchins who ‘make up’ those new dance steps and the Black cook who wrote the last lines of the ‘Ballad of Jesse James.’ Ask the man who, deprived of an electronic guitar, picked up a wash board and started to play it. The Rhyming Fool who sits in Re'‐mote Mississippi and talks ‘crazy’ for hours. The dazzling paradizing pun ning mischievous pre‐Joycean style play for Cakewalking, your Calinda, your Minstrelsy give‐and‐take of the ultra‐absurd. Ask the people who put wax paper over combs and blow through them. In other words, Nathan, I am saying Open‐Up‐To Right‐Here.”

The book is like that, frankly and consummately freewheeling, part historical funferal, here a highbrow satire, here a low‐key farce, even roman a clef. The villain of the piece is a controversial book publisher named Hinckle Von Vampton who wears “a black patch on his eye from an old war wound.” But Hinckle Von Vampton also turns out to be thousand‐year‐old Crusader who has learned to cheat death through a secret diet. Reed loves to mix his elements: spiritualists with cops and robbers, literary criticism with caricature, “a little bit of jive talk and a little bit of North Africa,” romance and necromancy, Egyptology, etymology, bibliography, hagiography, poli tics, Teutonic knights, and marvelously bizarre headlines—“MUSCLE WHITE BAGS COON.”

I don't mean merely that “Mumbo Jumbo” is about such mysteries as HooDoo or VooDoo. “Black Herman walks to the bed, picks up her scarf, and casts it to the floor where it becomes a snake.” I mean that it attempts, through its deadpan phan tasmagoria of a plot, and through the black art of the Magus as storyteller, to achieve the kind of hold on the reader's mind that from ancient times and in primitive contexts has always been associated with the secret Word, the sacred Text.

The plot of “Mumbo Jumbo” is mind ‐ boggling. In the 1920's an epidemic called Jes Grew begins to infect the United States, especially its black citizens. Topsy said he “jes' grew,” but Reed traces the origins of the Jes Grew infection back to the Egyptian god Osiris. As the plague spreads in the 1920's, a worldwide conspiracy, the “Mu'tafikah(?),” be gins to seize African, Oriental, and native American art treasures from white museums “of Art De tention” in order to return them to the peoples who created them. Locked in deadly combat with this “Black Tide of Mud” are “an ancient society known as the Atonist Path” (Aton, the Sun God), “its military arm the Wallflower Order,” and the medieval Knights Templars. As someone in the book notices, “It has been an interesting 2000 years.”

But just what is this potent infection the author calls Jes Grew? “Ask Louis Armstrong, Bessie Smith, your poets, your painters, ask them how to catch it. Ask those people who be shaking their tambourines impervious of the ridicule they receive from Black and White Atonists, Europe the ghost rattling its chains down the deserted halls of their brains. Ask those little colored urchins who ‘make up’ those new dance steps and the Black cook who wrote the last lines of the ‘Ballad of Jesse James.’ Ask the man who, deprived of an electronic guitar, picked up a wash board and started to play it. The Rhyming Fool who sits in Re'‐mote Mississippi and talks ‘crazy’ for hours. The dazzling paradizing pun ning mischievous pre‐Joycean style play for Cakewalking, your Calinda, your Minstrelsy give‐and‐take of the ultra‐absurd. Ask the people who put wax paper over combs and blow through them. In other words, Nathan, I am saying Open‐Up‐To Right‐Here.”

The book is like that, frankly and consummately freewheeling, part historical funferal, here a highbrow satire, here a low‐key farce, even roman a clef. The villain of the piece is a controversial book publisher named Hinckle Von Vampton who wears “a black patch on his eye from an old war wound.” But Hinckle Von Vampton also turns out to be thousand‐year‐old Crusader who has learned to cheat death through a secret diet. Reed loves to mix his elements: spiritualists with cops and robbers, literary criticism with caricature, “a little bit of jive talk and a little bit of North Africa,” romance and necromancy, Egyptology, etymology, bibliography, hagiography, poli tics, Teutonic knights, and marvelously bizarre headlines—“MUSCLE WHITE BAGS COON.”

Through all this, though he tells a fast‐paced story, the author plays fast and loose with the conventions of storytelling. For example, in the very midst of a kidnapping, the ten sion is interrupted to provide—as motive for the kidnapping itself — a long myth of Osiris, Moses and Jethro. Readers will find the ex perience rough, unless they are willing to put aside the usual ex pectations about what a novel is supposed to be, and the satisfaction it is rumored to provide. Ishmael Reed is unique, and he has other things to offer. If one stays with “Mumbo Jumbo,” uncannily, the book begins to establish its very own life, on its very own terms.

The terms are demanding. Reed wants to convince, not persuade. When William Golding unfolds his fable in “Lord of the Flies,” when Kurt Vonnegut spins his satire in “Cat's Cradle,” we are led to be lieve in the fantasy by a persuasive context: by tone, detail, characters, timing and drama. Disbelief is in fact easy to suspend because belief is what the audience craves and the storyteller loves to create. But Ish mael Reed, in the manner of William Burroughs, avoids persuasion, he in vites disbelief. Our very refusal (in ability) to lend credence to the lurid anti‐logic of “Naked Lunch” leaves us reeling—and then, if we can still turn pages at all, mesmerized by the novel's inner vision. Still, Bur roughs deals in junk nightmares, Reed in black ritual. “I . . . I don't want to be difficult with you, Hiero thant 1 says pressing the button so that 3 weird looking dudes in 3d Man Theme trenches enter through the doors leading to the round room. One carrys the ritual dagger on

Reed's tone here and elsewhere is curiously flat, opaque, hypnotic and carefully chosen. Earlier, in “The Freelance Pallbearers,” he displayed a prose style of considerable trans parency and brilliance. That first novel was a satire, too. A tale of slapstick and martyrdom; persua sive, but not convincing. His second novel, “Yellow Back Radio Broke Down,” was a Gnostic Western, a bizarre epic of cowpunching, hexing, execution and papal interven tion. So wild that there the question of belief could hardly arise. “Drag bent over and french kissed the animal be tween his teeth, licking the slaver from around the horse's gums.” “A novel,” the hero asserted after shooting his horse, “can be anything it wants to be, a vaudeville show, the six o'clock news, the mumbling of wild men saddled by demons.”

“Mumbo Jumbo” is all of these, but it is also sterner stuff than anything in his earlier books. The author is after bigger game now, and he has taken a risk. His terms in “Mumbo Jumbo” go beyond those of fiction. Beneath the passions of individual charac ters, beneath the conflict of blacks and whites, beneath every plague and blessing in the book, lies an opposition be tween the gods, between Osiris and Aton (compare Dionysos and Apollo). There is a prece dent, a novel at once satiric and holy: “The Golden Ass” of Apuleius written for the an cient sect of Isis. But that was long ago. And Reed sees the problem:

“A sacred Black Work if it came along today would be left unpublished.” It would be “the essential Pan ‐ Africanism . . . artists relating across contin ents their craft, drumbeats from the aeons, sounds that are still with us.” However, since the ancient Text is still missing, “we will make our own future text.”

So I suspect that for Ishmael Reed “Mumbo Jumbo” is some thing a good deal more than a novel. Through all the wild gy rations of its black comedy, he casts a nonfiction spell, he weaves an incantation with footnotes, he endows his Text with power. And if one reads it through, one risks succumbing to the Text . . . or as Reed once put it in a poem, disappearing into it.

The hunger of this poem is legendary it has taken in many victims.

Ishmael Reed's Mumbo Jumbo

by Ted Gioiahttp://fractiousfiction.com/mumbo_jumbo.html

In my writings on music, I have sometimes compared the dissemination

of a new performance style to the spread of a disease. This isn't just a

fancy metaphor. The mathematical models used to study the diffusion

of innovations come from medical science, and were originally developed

to predict the spread of epidemics. (Check out the work of Everett Rogersfor insights into this field of forecasting and trend analysis.)

In my twenties, when I worked as a management

consulting with McKinsey and the Boston Consulting

Group, I applied these formulas to plot the success

of new product launches and forecast the impact of

technology shifts. Later I found that these same

mathematical models could help me understand

the early spread of jazz, blues and other musical

'epidemics' of the past and present. A new cultural

meme is a kind of germ, and often the very same

conditions that foster one also help spread the other.

In other words, it’s no coincidence that New Orleans,

the birthplace of jazz, was also one of the unhealthiest

cities in the US at the time that this music came of age.

I doubt that novelist Ishmael Reed ever practiced

management consulting, but apparently he learned the same lessons

about the diffusion of new musical styles. In his 1972 novel Mumbo

Jumbo, Reed writes the story of an 'epidemic' of black culture—song,

dance, slang and other elements—spreading into mainstream America.

He calls his plague 'Jes Grew' and it is spread by 'Jes Grew Carriers'

(or J.G.C.s) who are responsible for outbreaks throughout the US, and

in some locations overseas.

Reed sets most of his story in New York during the Jazz Age. An earlier

outbreak of 'Jes Grew'—associated with the rise of ragtime in the

1890s—had been effectively contained. But now a new, stronger bug

is sweeping northward from New Orleans, and threatens to subdue

most of the population. There are "18,000 cases in Arkansas, 60,000

in Tennessee, 98,000 in Mississippi and cases showing up even in

Wyoming." Workers are dancing the Turkey Trot during their lunch break,

and singing in the streets. The authorities are alarmed. People want to

catch this new disease. Those who are still healthy gather around those

already bitten by the bug, and chant "give me fever, give me fever."

But if everyone wants to jump on the bandwagon of the new black plague,

who is left to stop it. Here Reed outdoes himself, offering the grandest of

conspiracy theories. The Knights Templar, apparently disbanded in the

year 1312, are actually still hanging around, and waiting for a chance to

stop the Jes Grew epidemic. But they need to get in line. The Teutonic

Knights, founded in the twelfth century, also want to block the disease.

And some Masons, a former cop, yellow journalists, Wall Street,

politicians the folks at the Plutocrat Club, and a mysterious group

known as the Wallflower Order, dedicated to implementing the world-

view of an even bigger conspiracy group, known as the Atonists, all

have skin in the game (literally and metaphorically).

And this conspiracy has been around for a long, long time. Take the

aforementioned 'Atonists', for example. Back in ancient Egypt, they

worshipped the disk of the sun, known as Aton, but now they represent a

coalition of angry monotheists, with everyone from Christians to Freudians

offering their support.

How can you keep a conspiracy this big a secret? And continue to

keep it secret for thousands of years? Reed doesn't tell us. Fortunately

a few brave souls have figured out the dark, dirty truth, and are willing to

take on this enormous coalition of evil doers—in particular, Papa La

Bas of the Mumbo Jumbo Kathedral, an upholder of African spiritualism,

and his ally Black Herman, a real-life African-American stage magician

who performed through the United States during the 1920s and early

1930s.

Other historical figures, from Warren G. Harding to King Tut, make

their appearance in cameo roles in this book. Three years after Reed

published Mumbo Jumbo, E.L. Doctorow released his novel Ragtime

to great acclaim, with particular praise lavished on that book’s mixture of

fictional characters and real personages from early 20th century America.

But Reed set the tone for this mashup up truth and fiction in his colorful

predecessor, and even anticipated Doctorow's reliance on black music

as an emblem for the flux and flow of the era.

If anything, Reed is more ambitious. He even includes footnotes and a

lengthy bibliography at the end of his novel—with citations of everyone

from Edward Gibbon to Madame Blavatsky. Photos and artwork are

also inserted into the text, which often seems intent on breaking free of

the constraints of the novel, and turning into a radical reinterpretation of

the last several thousand years of human society.

This book is packed to the brim with symbols and vaguely coded

references. For example, the leader of the Knights Templar’s efforts

to stamp out Jes Grew is a journalist named Hinckle Von Vampton.

Students of American literary history will easily recognize a parody of

white Harlem Renaissance advocate Carl Van Vechten (1880-1964).

Reed describes Von Vampton as having one blue eye, and wearing a

black eyepatch over the other eye—typical of the extravagant symbolism

that shows up again and again in this book, and a fitting way of depicting

Van Vechten's role as an intermediary between white and black culture.

But how many readers also pick up on the reference to Warren Hinckle,

a flamboyant San Francisco journalist who was at the peak of his fame

when Mumbo Jumbo was published, and cut a striking figure in town with

a black eyepatch?

Toward the conclusion of Mumbo Jumbo, Reed abandons his main

characters for thirty pages of revisionist history, ("Well, if you must know,

it all began 1000s of years ago in Egypt…") The campy, over-the-top

style of delivery may convince you that Reed is offering a parody of

conspiracy theories. But his intensity and earnestness also send a

message that he believes in them too. This tension is unresolved,

and I suspect that choice is deliberate. Reed wants to have it both ways:

he demands us to take his Atonist conspiracy seriously, but also wants

to maintain the flamboyant, comic tone that makes it laughable as well.

Yet readers may be confused at the end result. Does Ishmael Reed

really believe that Scott Joplin was institutionalized and given electro-

shock treatments by enemies of black music? Does he really think

that Warren G. Harding was our first African-American president

before Barack Obama? Is he actually contending that the Roman

Emperor Julian was assassinated by Christians? Does he really

believe that space ships landed in pre-Columbian Mexico?

In other words, Reed has delivered a classic work in the literature of

paranoia. He joins an illustrious company, offering us a book that can

stand alongside—at least in terms of the breadth of its conspiracy

theories—Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, Umberto Eco’s

Foucault’' Pendulum, Robert Heinlein’s The Puppet Masters, Robert

Anton Wilson's The Illuminatus Trilogy, Kurt Vonnegut’s The Sirensof Titan and other powerful literary evocations of our zeal to find hidden

enemies everywhere we look. Writers nowadays may do some things

better than their predecessors, but the generation that lived through

McCarthyism, the Cold War, Alger Hiss and Kim Philby had a much

better skill at capturing the exotic flavor of the paranoid mindset in

narrative form.

So you are best served if you come to this novel with a deep knowledge

of history—and not just American history, given the ever expanding

scope of Reed's concerns and conspiracies. The knowledgeable reader

will decipher many of the half-hidden references and apply good judgment

in deciding how many of Reed's "facts" can be believed. Others can

come along for the ride, and enjoy the color and pageantry of this novel.

But they need to remember the definition of mumbo jumbo, which (like

this novel, given that appropriate name) is a style of speaking in which

it's hard to separate gospel truth from good showmanship.

Ted Gioia writes on literature, music and popular culture. His most recent book is

The Jazz Standards: A Guide to the Repertoire.

Expanded Course in the History of Black Science Fiction: Mumbo Jumbo by Ishmael Reed

In February of 2016, Fantastic Stories of the Imagination published an essay by me called “A Crash Course in the History of Black Science Fiction.” Since then Tor.com has published my in-depth essays on nine of the 42 works mentioned. The original “Crash Course” listed those 42 titles in chronological order, but the essays skip around a bit. This tenth one talks about Ishmael Reed’s magnum opus, Mumbo Jumbo.

JES GREW

Mumbo Jumbo is the story of a life-giving epidemic known colloquially as “Jes Grew,” a spiritual cure-all for soullessness sweeping across the continental U.S. during the 1920s. If the book has a human hero it’s Papa LaBas, a self-anointed houngan—that is to say, a priest of ancient African mysteries. LaBas searches alongside Jes Grew for its long-lost sacred text in the hope of grounding and legitimizing it, and thus defeating the prudish rulers of the status quo. Jes Grew is a natural force manifesting as music, love, literature, gardening, art, sex, cooking—manifestations that are the province, in my religious tradition, of Oshun, the deity in charge of luxury and abundance. And also of sudden evolutionary advancement—Oshun shows up on the scene and the universe expands to include divination, poetry, and other powerful improvements. Sans text, though, Jes Grew’s operation is limited to frivolous realms: dance crazes, fashion trends, and so forth.

Mumbo Jumbo is the story of a life-giving epidemic known colloquially as “Jes Grew,” a spiritual cure-all for soullessness sweeping across the continental U.S. during the 1920s. If the book has a human hero it’s Papa LaBas, a self-anointed houngan—that is to say, a priest of ancient African mysteries. LaBas searches alongside Jes Grew for its long-lost sacred text in the hope of grounding and legitimizing it, and thus defeating the prudish rulers of the status quo. Jes Grew is a natural force manifesting as music, love, literature, gardening, art, sex, cooking—manifestations that are the province, in my religious tradition, of Oshun, the deity in charge of luxury and abundance. And also of sudden evolutionary advancement—Oshun shows up on the scene and the universe expands to include divination, poetry, and other powerful improvements. Sans text, though, Jes Grew’s operation is limited to frivolous realms: dance crazes, fashion trends, and so forth.SF OR F?

If there was ever a narrative that questioned received wisdom as to what constitutes stories of “magic” versus stories of “science,” Mumbo Jumbo is it. Challenging the validity of expectations for detachment and standardized replication associated with the scientific method, Reed makes a strong case that participation is a form of observation and variation on what’s observed is normal. Is his version of 2000 years of cultural trends and conspiracies based on a testable hypothesis? No. And yet he does examine the effects of the belief in and practice of magic on its adherents and opponents. Within the pages of Mumbo Jumbo, adherents of notoriously squishy social sciences such as anthropology Charleston madly with farmer-priests versed in divine agronomy; tracing the influence of Isis-and-Horus worship through reverence for Christianity’s Virgin Mary, the author arrives at surprising conclusions about the supposedly-objective Dr. Sigmund Freud’s bias towards the importance of the bonds between mother and child.

TRUE LIES, GRAPHIC CONTENT, SACRED SLANG

Mumbo Jumbo jumps back and forth over other boundaries besides those dividing the rational and the mystical. Illustrations liberally adorn its main body, free of captions, unrestricted to appendices. They comment on the writing as much as the writing comments on them. Quotations from and appearances by historical figures wind themselves in and out of Reed’s account of Jes Grew’s exploits. And in a metatextual moment the author has a character refer to his own Prince-like orthographic irregularities: Black Mason and famed number banker Buddy Jackson points out during an armed showdown with the Knights Templar that “The Charter of Daughters of the Eastern Star as you know is written in our mystery language which they call slang or dialect.”

SOME SORT OF CONTEXT

Mumbo Jumbo was finished, per the note Reed made at its end, at 3:00 p.m. on January 31, 1971, and published in 1972. I was 16 years old. Much of what’s now labeled “the 60s” was actually the early 1970s. I am here to tell you that in “the 60s” we believed we were about to save the world. Yes, my mother told me that was a naïve attitude. In vain. Books like this one convinced me and my peers we were in the throes of a new Jes Grew manifestation: the Funky, Downhome Dawning of the Age of Aquarius—and if its original liturgical text had been lost perhaps, as Reed hinted, we could write a new one!

Or perhaps Mumbo Jumbo was it. Reed had already wowed readers with The Freelance Pallbearers in 1967 and Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down (a “hoodoo Western”) in 1969. This latest might be his greatest, and who was to say his greatest couldn’t help us willing Jes Grew Converts re-enchant the world?

Who’s to say it didn’t?

PROMINENT J.G.C.s

Today, dozens of novels, awards, grants, art installations, lectures, poetry collections, anthologies, songs, essays, plays, and film scripts later, Ishmael Reed is a mighty and continuing influence on writers everywhere. Me for sure. Renowned Black publisher, editor, and author Bill Campbell claims that if not for Mumbo Jumbo, his wildly iconoclastic novel Koontown Killing Kaper just plain wouldn’t exist.

Victor LaValle, Colson Whitehead (whose novel The Intuitionist is also part of my “Crash Course”), and Reed’s former student Terry McMillan have also been influenced by this genius. I’m sure there must be many more.

GUN BARREL INFO DUMP

Some call Mumbo Jumbo a hoodoo detective novel, a revamping of the genre akin to Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down’s revamping of the Western. Certainly it can be read that way, with Papa LaBas the somewhat anachronistic private investigator and Jes Grew his elusive client. In that light the 30-page info dump toward the book’s end is only a rather extreme rendition of a bit typically found at a mystery’s denouement—you know, the part in which suspects and survivors are treated to a summarizing disquisition at the point of a pistol? Only this summary starts millennia ago in Egypt and finishes up circa 1923.

HOW MANY YEARS TO GO?

Reed’s several references to a previous bout of Jes Grew in the 1890s imply that its cyclical resurgences can’t be anticipated with clocklike regularity. Roughly three decades pass between that round of the epidemic and the one Mumbo Jumbo recounts. Another five passed between the events the novel depicts and its publication at a time when it seemed like we were experiencing a new bout of this enlivening “anti-plague.”

When are we due for the next one? Let’s get ready for it as soon as we can.

Nisi Shawl is a writer of science fiction and fantasy short stories and a journalist. She is the author of Everfair (Tor Books) and co-author (with Cynthia Ward) of Writing the Other: Bridging Cultural Differences for Successful Fiction. Her short stories have appeared in Asimov’s SF Magazine, Strange Horizons, and numerous other magazines and anthologies.

Nisi Shawl is a writer of science fiction and fantasy short stories and a journalist. She is the author of Everfair (Tor Books) and co-author (with Cynthia Ward) of Writing the Other: Bridging Cultural Differences for Successful Fiction. Her short stories have appeared in Asimov’s SF Magazine, Strange Horizons, and numerous other magazines and anthologies.

Uprising in Storyville:

Conjuring Resistance in African-American

Literature

Tom Tàbori (University of Glasgow)

https://www.gla.ac.uk/media/Media_122693_smxx.pdf

‘[Ishmael] Reed’s rhetorical strategy assumes the form of the

relationship between the text and the criticism of that text, which

serves as discourse upon the text’ (Gates 1988, p.112). So speaks

Henry Louis Gates Jr. in his seminal text The Signifying Monkey,

harnessing, he believes, Mikhail Bakhtin’s theory of ‘inner

dialogisation’ (1988, p.112), or polemic hidden in parody. He does

this to argue the case for self-reflexivity as Mumbo Jumbo’s ‘form of

signifyin(g)’(Hurston 1990, cited in Gates 1988, p.113), the way in

which Reed riffs on the codes fielded in his text. However, what

Gates declines to explore are the discourses to which these codes

pertain, discourses that Reed summons like a conjuror, then

performs like a ventriloquist; the very social currents that lace his

America and are re-laced in his text. To avoid the connotation of

illusory, David Blaine-style conjuring, this essay will posit in its place

the term conjure, as it relates to the conjure man, a pervasive

archetype within African-American literature. He is both community

organiser and a reality re-organiser, conjuring uprising from what

already-exists, not out of the blue, and this conjure is present in the

works of Ishmael Reed, Rudolph Fisher, and Randolph Kenan

which this essay will examine.

Even after the sociality of conjure is returned, the radicalism

and reach of this ‘form of signifyin(g)’(Hurston 1990, cited in Gates

1988, p.113) is restricted by critics who file it away as Reed’s

idiosyncrasy, such as James Lindroth’s Images of Subversion and Helen

Lock’s A Man's Story Is His Gris-gris (Lindroth 1996; Lock 1993). In

response, this essay will show that Reed’s ‘Neo-HooDoo, …the Lost

American Church’(2004b, p.2062), is part of a grander narrative of

conjure within African-American literature.

To this end, the essay will look at the generations prior and successive

to Reed, in order to fashion a theory of conjure as a narrative adapted

to the uprootednessof a people hauled across the Atlantic: ‘we were

dumped here on our own without the book to tell us who the Loas are,

what we callspirits… [so] we made it all up on our own’ (Reed 1996, p.130).

African-American literature’s interiority to America levies the

commitment that is this essay’s first theme: giving the individual no

opt-out from the relationships of difference into which he is born,

and giving Reed the belief that ‘a black man is born with his guard

up’ (Reed 1990, epigraph). The second theme is parody itself, an act

of doubling involved in what Bakhtin calls ‘the reaccentuation of

images and languages (forms) in the novel’ (1981, p.59), essentially a

storytelling technique by which the past can be played and replayed,

memories conjured up to furnish the present, rather than one-way

bombardment, or Proustian moments. The third aspect of conjure

and the third theme of this essay is the act of occupying, as used by

the Loop Garew Kid in Reed’s Yellow-Back Radio Broke Down, when,

‘by making figurines of his victims he entraps their spirits and is able

to manipulate them’ (2000, p.60). Each theme makes a point about

decentredness, the relational subjectivity of those separated from their

origins by the Atlantic. Each theme remarks that decentredness does

not disable resistance but, rather, enables the double-voicing that can

negotiate such a compromised position. This is what lets the

conjuror stays focused behind enemy lines, behind the mask, as a

storyteller trapped in his own story, with access to a host of ciphers

for him to talk through, structures for him to ride on, and social

apparatus on which ‘to swing up on freedom’(Malcolm X 2004,

track 21).

Conjuring Resistance in African-American

Tom Tàbori (University of Glasgow)

https://www.gla.ac.uk/media/Media_122693_smxx.pdf

‘[Ishmael] Reed’s rhetorical strategy assumes the form of the

relationship between the text and the criticism of that text, which

serves as discourse upon the text’ (Gates 1988, p.112). So speaks

Henry Louis Gates Jr. in his seminal text The Signifying Monkey,

harnessing, he believes, Mikhail Bakhtin’s theory of ‘inner

dialogisation’ (1988, p.112), or polemic hidden in parody. He does

this to argue the case for self-reflexivity as Mumbo Jumbo’s ‘form of

signifyin(g)’(Hurston 1990, cited in Gates 1988, p.113), the way in

which Reed riffs on the codes fielded in his text. However, what

Gates declines to explore are the discourses to which these codes

pertain, discourses that Reed summons like a conjuror, then

performs like a ventriloquist; the very social currents that lace his

America and are re-laced in his text. To avoid the connotation of

illusory, David Blaine-style conjuring, this essay will posit in its place

the term conjure, as it relates to the conjure man, a pervasive

archetype within African-American literature. He is both community

organiser and a reality re-organiser, conjuring uprising from what

already-exists, not out of the blue, and this conjure is present in the

works of Ishmael Reed, Rudolph Fisher, and Randolph Kenan

which this essay will examine.

Even after the sociality of conjure is returned, the radicalism

and reach of this ‘form of signifyin(g)’(Hurston 1990, cited in Gates

1988, p.113) is restricted by critics who file it away as Reed’s

idiosyncrasy, such as James Lindroth’s Images of Subversion and Helen

Lock’s A Man's Story Is His Gris-gris (Lindroth 1996; Lock 1993). In

response, this essay will show that Reed’s ‘Neo-HooDoo, …the Lost

American Church’(2004b, p.2062), is part of a grander narrative of

conjure within African-American literature.

To this end, the essay will look at the generations prior and successive

to Reed, in order to fashion a theory of conjure as a narrative adapted

to the uprootednessof a people hauled across the Atlantic: ‘we were

dumped here on our own without the book to tell us who the Loas are,

what we callspirits… [so] we made it all up on our own’ (Reed 1996, p.130).

African-American literature’s interiority to America levies the

commitment that is this essay’s first theme: giving the individual no

opt-out from the relationships of difference into which he is born,

and giving Reed the belief that ‘a black man is born with his guard

up’ (Reed 1990, epigraph). The second theme is parody itself, an act

of doubling involved in what Bakhtin calls ‘the reaccentuation of

images and languages (forms) in the novel’ (1981, p.59), essentially a

storytelling technique by which the past can be played and replayed,

memories conjured up to furnish the present, rather than one-way

bombardment, or Proustian moments. The third aspect of conjure

and the third theme of this essay is the act of occupying, as used by

the Loop Garew Kid in Reed’s Yellow-Back Radio Broke Down, when,

‘by making figurines of his victims he entraps their spirits and is able

to manipulate them’ (2000, p.60). Each theme makes a point about

decentredness, the relational subjectivity of those separated from their

origins by the Atlantic. Each theme remarks that decentredness does

not disable resistance but, rather, enables the double-voicing that can

negotiate such a compromised position. This is what lets the

conjuror stays focused behind enemy lines, behind the mask, as a

storyteller trapped in his own story, with access to a host of ciphers

for him to talk through, structures for him to ride on, and social

apparatus on which ‘to swing up on freedom’(Malcolm X 2004,

track 21).

Infecting the Academy: How Reconfigured Thought Jes Grew from Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo. (2011)

PIATKOWSKI, PAUL DAVID, M.A.https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/Piatkowski_uncg_0154M_10848.pdf

73 pp.

The world of academic study and university education privileges a so-called

“global” process of thinking as universal, but this process actually relies on practices with

a European centrality. This thinking process gets taught to individuals and “programs”

the manner of thinking for the majority of the world’s population, serving a neocolonial

purpose in global conversations. After first revealing that Western civilization’s

institutions of learning propagate a disorienting perspective for other ethno-cultural

viewpoints, Ishmael Reed utilizes a discursive process called Jes Grew that parasitically

rewrites the institutionalized hegemony of the Western academy and its influence on the

arts, thoughts, and actions of other ethno-cultural groups.

In his novel Mumbo Jumbo, Ishmael Reed uses Jes Grew, a type of infovirus, to

recode both the reader of the text and the academy itself through de-centering and

deconstructing academic practices and texts of Western civilization, and then

reconstructing and rewriting these into a more fluid, unbound academic system not

circumscribed within the confines of Eurocentric hegemony. Reed accomplishes this task

with the construction and implementation of Jes Grew that he first seeds in the imaginary

and then extends out into physical, lived reality. Through a deconstruction of the physical

and fictional text and an analysis of Reed’s structural approach in Mumbo Jumbo, it

becomes clear that his target hosts for Jes Grew infection are academic readers. Reed

begins his process by shifting a European paradigm to an African one, and through this

process he de-centers the “universal” centrality of Western culture. Reed’s Jes Grew

rewrites thinking into a system of thought that equally privileges multiple ethno-cultural

viewpoints by de-centering and deconstructing the infected reader and re-centering the

academic manner of processing information. This process de-privileges a Western

manner of thinking and creates, instead, a fluid, unbound method of processing

knowledge. Jes Grew reconfigures thinking itself in a manner that decolonizes the global

psyche

Ishmael Reed's 1972 novel Mumbo Jumbo mobilises a history of culture which

recognises African antecedents to a specific African-American tradition, but as this

history of culture focuses on the notion of 'possession', as exemplified by the Afrodiasporan system of voodoo, the notion that an African history could constitute a history

of' origins' is revealed to be rather ridiculous. The figure of being 'possessed', or of

'going out of one's head' is used equally well in this novel to indicate vodoun rites as it is

to signify the function of memory, and similarly, emphasises the fluidity of any perceived

'difference' between these concepts. Reed's figure of 'Jes Grew' may be imagined to be

a collective term for possessive forces, as well as for the state of being possessed, and

while it is linked to a tradition specific to African-American, Caribbean and African

cultures, it is also a state which may be known to anyone who is able to present the right

frame of mind to receive it. As a memory of Africa can be 'remembered' within the

terms of a linear history, then, memory also functions as 'possessive' action, allowing a

connection to Africa to arise at any given moment. Reed draws a history of culture back

to Ancient Egypt in this novel, thereby presenting a tradition, but at the same time sends

up any tendency to attach this tradition to the sign of 'blackness', as indicative of a

narrow, "Atonist", notion of signification which perceives the relationship between

language and memory as purely linear. Reed makes a profoundly comic commentary

upon the notion of African 'origins' here, as he situates Africa not as the site of the

33

origins of African diasporan culture, but of the' Atonist' perspective itself which he

figures as a particularly Euro-American neurosis toward tradition and the past.

As the novel's "anti-plague",l Jes Grew is figured in the novel as both a distinct tradition

and a possessive force which appears in discrete historical moments, and Reed "turn[s] to

Egypt not just as proof of a black African past but as a model for contemporary

spirituality and culture", and imagines "each moment [ ... ] in a kind of continuous

awareness of and interdependence with the others".2 In this novel which spoofs the hardboiled detective story genre,3 not least by drawing 'back to Africa' an extremely

convoluted history of a plague which manifests itself in instances of "suggestive bumping

and grinding" and "wild abandoned spooning" (22), Reed must be seen to be responding

with laughter to earnest attempts to discover something 'meaningful' about culture by

way of deciphering histories of 'origins'. So J es Grew is shown to characterise the 1920s

'Harlem Renaissance' - "The Blues is a Jes Grew, as James Weldon Johnson surmised.

Jazz was a Jes Grew which followed the Jes Grew of Ragtime. Slang is a Jes Grew too."

(214) It is also shown to be both a repetition of and a parallel to previous eras, as the end

of the novel also depicts the 1970s as a time when "Jes Grew was [again] latching onto

its blood" (216), and its lineage is furthermore charted to an Ancient Egyptian "theater

accompanying [ ... ] agriculturalists' rites" (161). Even as Jes Grew is shown to be

illustrative of an African-American and African tradition, it is also a possessive force-

"'Jes Grew is life" (204) itself - and the novel shows that it can arise at any given

moment, and is available to anyone who presents the frame of mind to receive it. The

memory of Africa is thus felt to be intrinsic to an African-American tradition, to be the

site of a form of life depicted as 'natural', and yet also to be the site of a confrontation

between a fluid form of memory, and what is presented as the 'unnatural' attitudes

toward the past represented by Atonism.

Reed's perspective in this novel is rooted in a tradition he calls "N eo Hoodoo because it

doesn't begin with me", 4 and which is related to voodoo, which Reed regards as a

"common language" which "not only united the Africans but also made it easier for them

to forge alliances with those Native Americans whose customs were similar".5

Explaining that "hoodoo involved art [ ... ,]dancing, painting, poetry, it was multimedia",6 Reed understands it to be "what Black Americans came up with", "as opposed

to Obeahism in Jamaica and other islands and Voodooism in Haiti", 7 but that it is still

"based upon African forms of art". 8 For Reed, Helen Lock explains,

Neo-HooDoo's purpose is to give new life to marginalized and apparently moribund

cultural sensibilities, as Jes Grew had become, by fusing African and Euro-American aesthetic traditions into a new African-American aesthetic, according to which orality and

literacy, past and present, fonn and spirit are all equally privileged, and cultural integrity

both preserved intact and enriched. "This is what my writing is all about. It leads me to

the places where I can see old cultures resurrected and made contemporary. Time past is

time present".

CONTINUE READING CHAPTER ONE

http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/4110/1/WRAP_THESIS_Kamali_2007.pdf

Spectres of the Shore: The Memory of Africa in

Contemporary African-American and Black British

Fiction

by

Leila Francesca Kamali

A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for

the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

In

English and Comparative Literary Studies

University of Warwick,

Department of English and Comparative Literary Studies

May 2007

CONTINUE READING CHAPTER ONE

http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/4110/1/WRAP_THESIS_Kamali_2007.pdf

Spectres of the Shore: The Memory of Africa in

Contemporary African-American and Black British

Fiction

by

Leila Francesca Kamali

A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for

the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

In

English and Comparative Literary Studies

University of Warwick,

Department of English and Comparative Literary Studies

May 2007

ART

FEATURE: ‘MUMBO JUMBO’ BY ISHMAEL REED: AN INFECTIOUS MASTERPIECE OF BLACK LITERATURE

By Eye Candy

April 15, 2015

It’s 1920 and Harlem is in havoc, thousands around the city are “suffering” from “Jes Grew”, the mysterious “disease” that’s got people out in the streets jumping, bouncing, and feverishly thrusting their bodies in a superhuman trance. No one can contain this epidemic; it’s sweeping across the nation, infecting thousands of people and forcing them into a sudden and unpredictable dance craze. They lose control of their bodies and can’t help but groove and shake rhythmically to its beat—this is the lively backdrop of Ishmael Reed’s mystifying 1972 novel Mumbo Jumbo.

By Damola Durosomo, AFROPUNK Contributor

Mumbo Jumbo is a satirical masterpiece, a critical analysis of Western culture and its blatant disregard for Africa and the meaningful contributions of its people. Reed shifts back and forth between various historical time periods and presents an array of quirky, archetypical characters, each symbolic of certain religious, social and political ideologies. PaPa LaBas is the head of the Jes Grew Kathedral, he calls himself a “Neo-HoDoo therapist”, who is dedicated to conserving traditional African religions and is a staunch supporter of Jes Grew. According to PaPa LaBas, Jes Grew is far from a deadly disease, rather it is an extremely pleasurable and freeing mental and physical state for those it inhabits, encouraging them to move about freely and search for truth and meaning. He makes it his mission to preserve and spread Jes Grews to all non-Westerners. He does so with the help of the radical Jes Grew organization Mu’tahfikah, a group of Jes Grew carriers who go about sharing Jes Grew and raiding museums in order to reclaim African and Asian cultural artifacts and return them to their places of origin. In Mumbo Jumbo, Papa LaBas and his crew are meant to exemplify black consciousness and a purely Afrocentric worldview, a firm belief in the idea that black people are purveyors of culture who have made invaluable contributions to society that Western culture has tried to either steal or suppress. PaPa LaBas and Mu’tahfikah attempt to counteract this by disseminating Jes Grew and awakening the masses.

On the opposite side of the spectrum, we have Hinckle Von Hampton, the owner of the sacred Jes Grew text, written by ancient Egyptians, which posses the power to control the epidemic. Von Hampton and his team, the Wallflower Order, go to great lengths to avert the increasing influence of Jes Grew. The most bizarre of these attempts is their disgraceful effort to create what they refer to as a “Talking Droid” modeled after a charming, well-educated black man that will trick black populations into believing that Jes Grew is harmful and dangerous to them. By endeavoring to subdue Jes Grew—a discernable and instrumental product of black culture—Hinkle Van Hampton serves as an emblem of the Western world and the efforts made by the media—as well as social and political institutions—aimed at obscuring the achievements of people of the African diaspora in order to maintain the flawed perception of Western cultural superiority. Jes Grew promotes black culture and enlightens its victims; making it a threat to white, Western rationalistic thought. Therefore, it must be “cured”.

Reed’s style is amusing and unconventional. Mumbo Jumbo reads almost as a movie script with seemingly random black and white photographs and catchy newspaper headlines in between. Ishmael’s brilliant use of satire gives Mumbo Jumbo the rare quality of being subtle and blunt at the same time. Through this, Reed provides remarkably sharp and thought-provoking racial commentary.

Though written in 1972, the central motifs discussed in Mumbo Jumbo are still incredibly relevant. Cultural appropriation on the part of white America is ever-present and media portrayal of young black men and women is habitually misconstrued. White people continue to dominate social, economic and political affairs and Western culture remains the prevailing global standard while the immeasurable contributions of black, African people continue to be undermined and overlooked; these are the things that need to be “cured”. There are definite parallels between the events that take place in Mumbo Jumbo and current events. Just like in the colorful streets of Harlem in 1920, a Jes Grew epidemic—a widespread condition of physical, intellectual and spiritual liberation—may be just what we need.

Words by EYE CANDY

ISHMAEL REED’S HOODOO DETECTIVE

The 1972 cult crime novel that explores Black identity, African religion, civilizations at war, and all of recorded history.

APRIL 6, 2020 BY SCOTT ADLERBERG

https://crimereads.com/ishmael-reeds-hoodoo-detective/

Most detective novels tell a story about a local crime. But what about the crime stories much bigger? I don’t mean stories, say, about government corruption or drug smuggling or international human trafficking. These tales present us with crimes grave and damaging enough, but every so often, in a mystery novel, you’ll find a detective coming up against something even larger in scope. Ishmael Reed’s 1972 book, Mumbo Jumbo, provides one such example. You might say the novel’s criminal is nothing less than recorded history. Yes, history itself is the culprit in these pages, and the specific crime is the oppression, the stifling, the diminishment, of one civilization by another. It takes an unusual type of detective to investigate a case with implications so broad, and that’s where Reed’s investigator, PaPa LaBas, described as an “astro-detective”, comes in.

It’s the early 1920s, in New York City. Papa La Bas works out of Harlem, his office located in a two-story building named The Mumbo Jumbo Kathedral, and his purported strong ties to Africa are clear in how he’s introduced:

“Some say his ancestor is the long Ju Ju of Arno in eastern Nigeria, the man who would oracle, sitting in the mouth of a cave, as his clients stood below in shallow water.”

“Another story is that he is the reincarnation of the famed Moor of Summerland himself, the Black gypsy who according to Sufi Lit, sicked the Witches on Europe. Whoever his progenitor, whatever his lineage, his grandfather, it is known, was brought to America on a slave ship mixed in with other workers who were responsible for bringing African religion to the Americas where it survives to this day.”

Papa La Bas is enigmatic even to his friends and acquaintances, but what is important to know about him, as the narrator states, is that he carries “Jes Grew in him like most other folk carry genes.” Since the case he tackles will concern the powerful force called Jes Grew and the efforts by its enemies to suppress it, LaBas is both qualified for the job at hand and eager to do it. Nobody has to pay him to take it on.

But what exactly is Jes Grew?

As Mumbo Jumbo lays it out, Jes Grew is a virus. It’s a plague that has struck different parts of the United States over the years. At times, it has hit Europe. But unlike other plagues, Jes Grew doesn’t ravage the affected person’s body; it enlivens the host. It’s described as “electric as life” and “characterized by ebullience and ecstasy.” And wouldn’t you know it, the reason it came to America had to do with cotton. It arrived with the people brought to this country to pick the crop Americans, inexplicably, wanted to grow.

When Mumbo Jumbo opens, during the Warren Harding presidency, a new Jes Grew outbreak has flared. It had swept through the United States in the 1890s, around the time Ragtime became popular, but authorities managed to squelch it. Now it’s back, in a stronger variant, having begun in New Orleans and then gone on to tear through cities throughout the country. From how it makes people behave, there can be no doubt what it represents. And it’s no surprise why people quoted as fearing it—a Southern congressmen, Calvinist editorial writers—do regard it as a scourge. Jes Grew is life-affirming; it fosters a love of jazz, dancing, sexuality, pleasure. It doesn’t respect any monotheistic god, but more like vodoun, encourages an embrace and acceptance of “the gods.” It sharpens one’s senses, a Jes Grew patient says, and he declares that with Jes Grew “he felt like the gut heart and lungs of Africa’s interior. He said he felt like the Kongo: ‘Land of the Panther.’ He said he felt like ‘deserting his master,’ as the Kongo is ‘prone to do.’” Jes Grew, in other words, as its enemies see it, is a germ equated with Africa and blackness and African-American creativity. With the advent of the new outbreak, millions in the country are at risk, a situation the authorities consider dire. The United States itself is in grave danger, and perhaps all of Western Civilization.

If this does not sound like the plot material for a detective novel, that’s because Mumbo Jumbo is an unconventional one. In a 50-plus year career that includes poetry, playwriting, scriptwriting, essays. literary criticism, librettos, and songwriting, Ishmael Reed has produced eleven novels, and in none of them does he check his irreverence or follow orthodox narrative arcs. He satirizes westerns in Yellow Back Radio Broke Down (1970), the fugitive slave narrative in Flight to Canada (1975), the campus novel and American academic life in Japanese By Spring (1998). He critiques the media and everything related to the fallout from the OJ Simpson trial in Juice! (2011) and takes on the Trump era and relations between Indian Americans and African Americans in Conjugating Hindi (2018). In short, over six decades, Reed’s list of targets in American social and political life has been vast, his weapons for attack fearless humor and prodigious scholarship. He is a writer who weaves disparate elements into his novels: photos, cartoons, film allusions, oral histories, music, political rhetoric, boxing knowledge, folklore, citations from obscure historical tomes. Not unlike a writer similarly encyclopedic, Thomas Pynchon, who mentions Reed in Gravity’s Rainbow (“check out Ishmael Reed” Pynchon’s narrator tells us on page 588 of that book), Reed is a postmodernist, a master of literary bricolage. He never ceases to twist, parody, and subvert the tropes of the genre he’s using. So it goes in Mumbo Jumbo, where Reed makes it clear this is not a private eye novel like Raymond Chandler or his ilk would write. Still, for all Reed’s playfulness, his destabilization of a form, he does give the reader a real detective story. Reed says so himself, as Stephen Soitos writes in his book, The Blues Detective. In his essay “Serious Comedy in African-American Literature”, from Writin is Fightin, Reed says, “If there exists a body of mysteries in Afro-American oral literature, then included among my works would be mysteries like Mumbo Jumbo, which is not only a detective novel, but a novel concerning the mysteries, the secrets, of competing civilizations.”

Like many a detective, Papa La Bas searches for a missing object. In this case, as suits a novel in part about historical interpretation, the object is a text. It is the Jes Grew Text, the alleged written document linked to the origins of the Afrocentric virus that has broken out. As the narrator tells us, “Jes Grew is seeking its words. Its text. For what good is a liturgy without a text?”

The Text has a history extraordinarily convoluted, and one can’t help but think that Reed, at least somewhat, is parodying novels like The Maltese Falcon, in which the desired object dates back centuries and has passed through numerous bloodstained hands. In Mumbo Jumbo, the Jes Grew Text is connected to the never-ending battle between those under the sway of Jes Grew and those determined to eradicate the plague, called Atonists. Atonists include The Wallflower Order, a secretive international society, its members devoted to control of others, psychological repression, and monotheistic belief. As the reader gleans, this battle between the Jes Grew people and the Atonists began millennia ago. In a nutshell, the two sides represent eros and thanatos, the life force and the death force, and as the history of Western civilization has shown, the Atonists have long been winning. But is winning without total victory enough for them? Wherever the Jes Grew Text has gone (and nobody seems to know who has owned it from century to century), the virus has followed. The Atonists have never stamped Jes Grew out completely, and this infuriates them. As they see it, if they could only get their hands on the Text and burn it, they would be able to wipe out Jes Grew forever.

While the search for the Text unfolds in Harlem, Ishmael Reed blends actual events from the 1920s with total fiction. The U.S. occupation of Haiti figures prominently, and much is made of the rumor, well-known at the time, that Warren Harding had black ancestry. Dancer Irene Castle and bandleader Cab Calloway pop their heads in. A group of art liberators, the Mu’tafikah, storm museums so they can return to Africa the artwork stolen from that continent, and a white man named Hinckle von Vampton is the editor of the Benign Monster, a magazine whose mission it is to destroy the burgeoning arts movements in Harlem. To this end, von Vampton pretends to be an ally of blacks, a Negrophile, and hires a young black guy from Mississippi to write a Negro Viewpoint column. At the same time, he employs a “talking black android”; that is, a white man done up in black face who will write subtly pro-white columns for the magazine and thus undermine black ideas and creativity. Von Vampton also happens to be a Knight Templar who was alive as far back as 1118, and the Knights Templar, for centuries, have somehow been intertwined with the missing Jes Grew Text.

It’s a heady mix of characters and events, of shadowy forces taking on other forces, but through it all, PaPa La Bas remains unfazed. Perhaps this is because, as a friend of his says, he already hews to a “hypothesis about some secret society molding the consciousness of the West.” His friend criticizes him for this conspiratorial outlook, saying there’s no empirical evidence for it, but La Bas is a person, and an investigator, who has his own way of reasoning:

“Evidence? Woman, I dream about it, I feel it, I use my 2 heads, My Knockings. Don’t your children have your Knockings, or have you New Negroes lost your other senses, the senses we came over here with?”

NOT A DETECTIVE IN THE WESTERN MODE, EITHER A RATIOCINATIVE-LITTLE-GREY-CELLS TYPE OR A HARDBOILED GUMSHOE TYPE, LA BAS SIZES UP “HIS CLIENTS TO FIT THEIR SOULS.”

Not a detective in the Western mode, either a ratiocinative-little-grey-cells type or a hardboiled gumshoe type, La Bas sizes up “his clients to fit their souls.” His critics call his headquarters the Mumbo Jumbo Kathedral, but little do they know that mumbo jumbo is a phrase derived from Mandingo that means “magician who makes the troubled spirits of ancestors go away.” La Bas has a substantial impact; to heal his clients he works with “jewelry, Black astrology, charts, herbs, potions, candles, talismans.” He drives around Harlem in his Locomobile and does have the eccentric and distinctive appearance one might expect from a detective: “frock coat, opera hat, smoked glasses, and carrying a cane.” When Reed calls him “a noonday Hoodoo, fugitive-hermit, obeah-man, botanist, animal impersonator, 2-headed man, You-Name-It”, it’s to emphasize the dexterity, skills, and elusiveness of his character. As Stephen Soitos cogently puts it: “LaBas comes to us out of the African trickster tradition and resists definitive analysis”. The word Hoodoo ties LaBas to an amalgam of African religious practices brought to the United States by the enslaved and connects to what Reed calls his Neo-Hoodoo aesthetic. Neo-Hoodoo, as Reed formulates it, is a mixture of Hoodoo ritual, Afrocentric philosophy, and positive African American identity drawing on the past and the ever changing present. Reed states that “Neo-Hoodoo believes that every man is an artist and every artist is a priest. You can bring your own creative ideas to Neo-Hoodoo.”

In Mumbo Jumbo, Neo-Hoodoo is explicitly a means to resist the oppression and life-denying traits of the Atonists. La Bas and his ally and sometime sidekick Black Herman, an occultist, work using intuition, chance, and learning from non-Western sources. They embrace indeterminacy and do not elevate rationality, as countless detectives do, to a supreme value in and of itself. They do not work to restore a status quo that most detectives, through their use of deductive logic, wind up upholding. To quote the “Neo-Hoodoo Manifesto” again: “Neo-Hoodoos are detectives of the metaphysical about to make a pinch. We have issued warrants for a God arrest. If Jeho-vah reveals his real name, he will be released on his own recognizance and put out to pasture.”

In this passage, Reed is pitting his detectives against Christianity specifically, but in Mumbo Jumbo, his target is broader—a common type of reductive thinking that goes against the spirit of Neo-Hoodoo. When Hinckle Von Vampton advertises for his Negro Viewpoint columnist, one applicant says that his experience includes having read the 487 articles written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels and that he knows them by heart. Von Hinckle thinks, “the perfect candidate…He doesn’t mind the shape of the idol: sexuality, economics, whatever, as long as it is limited to the 1.” To a sworn opponent of Jes Grew, these qualifications please Von Vampton. He hires the man.

Similarly, Adbul Hamid, black Muslim storefront proselytizer in Harlem, displays a rigidity that earns criticism. In a discussion with PaPa La Bas and Black Herman about the Jes Grew epidemic, Hamid says that black people have to stop their dancing and carrying on, “fulfilling base carnal appetites.” No matter that blacks have been dancing for thousands of years, as La Bas tells him, or that dancing is “deep in the race soul”—to Hamid, it’s all just twisting of butts and getting happy in the old primitive jungle ways. “Allah is the way, Allah be praised,” he says, threatening Hell for those who don’t choose the right path, which prompts La Bas to tell him that he is no different than the Christians he imitates. “Atonist Christians and Muslims don’t tolerate those who refuse to accept their modes.” And as La Bas asks, “where does that leave the ancient Vodun aesthetic: pantheistic, becoming, 1 which bountifully permits 1000s of spirits, as many as the imagination can hold.”

Humor is essential to La Bas’ perspective also, a trait he connects to Africa and that further ties him to his trickster lineage. About halfway through the novel, inside Abdul Hamid’s Harlem office, La Bas sees some African art depicting Whites in centuries past in Africa, lampoon carvings done by African sculptors. The works make him think about how Western tradition has stifled and misshapen something essential to the African spirit:

“The African race had quite a sense of humor. In North America, under Christianity, many of them had been reduced to glumness, depression, surliness, cynicism, malice without artfulness, and their intellectuals, in America, only appreciated heavy, serious works…They’d really fallen in love with tragedy. Their plays were about bitter raging members of the ‘nuclear family,’ and their counterpart in art was exemplified by the contorted, grimacing, painful social-realist face. Somebody, head in hands, sitting on a stoop.”

For La Bas, anyone who can’t laugh a little bit is “not Afro but most likely a Christian connoting blood, death, and impaled emaciated Jew in excruciation.” La Bas can’t recall ever seeing an account or picture of Christ laughing. “Like the Marxists who secularized his doctrine, he is always stern, serious and as gloomy as a prison guard.” What a contrast that is to portraits one sees where Buddha is laughing or to “certain African loas, Orishas.”

La Bas is a detective who rarely has history far from his thoughts, and he uses his immense historical knowledge to make headway on his case. When he and Black Herman find Abdul Hamid dead in Hamid’s office, the search for the missing Jes Grew Text expands into a murder case, and the pieces start to cohere for La Bas.

Due to a note at the scene, a rejection slip, referencing a manuscript Hamid had, La Bas draws conclusions, and in classic mystery fashion, he finds a scrap of paper in Abdul’s fist that contains a clue. The writing on the paper says, “Epigram on American-Egyptian Cotton” and below that title, it reads:

“Stringy lumpy, Bales dancing

Beneath this center

Lies the Bird”

Somehow these words, without the reader quite knowing why, lead PaPa Las and Black Herman to Hinkle von Vampton, and they make a citizen’s arrest on von Vampton when Hinkle is attending a soiree in Westchester, New York. The guests don’t just allow La Bas, Herman, and the six tall Python men they’ve brought as muscle to take Hinkle, though. They want to know the meaning behind the seizure, what the charges against the accused are. Hinkle echoes this demand, and it’s here that La Bas gives the mystery novel explanation, the narrative by the detective that should clear up the preceding swirl of events. We sense it won’t be a typical explanation, however, when La Bas begins by saying, “Well, if you must know, it all began 1000s of years ago in Egypt.”

The story La Bas proceeds to tell runs thirty pages and puts forth a version of history the reader has never heard before. It criticizes and undermines the entire path Western civilization has taken. But history, as we’ve learned from this novel, needs major correctives. Those oppressed by history and denied their own narratives need to reclaim their history. PaPa La Bas explains, in language at once scholarly, colloquial, and funny, how the sought after Jes Grew Text derives from a sect that formed around the Egyptian god Osiris. If history had followed the example of Osiris, Western civilization would have taken a more nature-embracing and life-affirming path, but Osiris and his adherents were opposed at every turn and ultimately defeated by Set, Osiris’s brother. Set hated Osiris and Osiris’s popularity with the people. While Osiris would tour with his International Nile Root Orchestra, “dancing agronomy and going from country to country with his band,” Set fixated on taking control of Egypt. He attempted to banish music and outlawed dancing. He “went down as the 1st man to shut nature out of himself.” Set transformed worship in Egypt from the worship of multiple gods, “the nature religion of Osiris,” to the worship of one god, his “own religion based upon Aton (the sun’s flaming disc).” This crucial switch, to monotheism, would stand as the foundation on which the West developed. Equally ruinous, Set established the precedent of doing everything he could to erase Osiris’ work and spirit from history. Whether it has been the Catholic Church or poets such as John Milton or pillars of repression like Sigmund Freud, the Atonist cause has been advanced and defended, obliterating counter narratives. Atonists would have us believe that the course history has taken is the only way history could have gone.

And the Jes Grew Text? Where does that fit in? Written by Osiris’ helper Thoth, it apparently contains the essence of the rites Osiris practiced. Down through the centuries, it has moved around, a book deemed sacred and dangerous. La Bas discloses that Hinkle von Vampton, Knights Templar librarian, came upon the book in the Templar library in 1118, but hundreds of years later, after various intrigues, it wound up with Abdul Hamid in Harlem. Its presence in Harlem has led to the Jes Grew outbreak there, and when Hamid resisted von Vampton’s efforts to regain the book, Hinkle murdered him. This is the reason La Bas and Black Herman made their move to seize von Vampton.

* * *

The culprit in the case has been caught, and La Bas lets the assembled group know how he decoded the epigram Hamid left behind. Reminiscent of Poe’s “The Gold Bug,” in which the cracking of a cryptogram leads to the discovery of treasure beneath a tree, La Bas’ understanding of Hamid’s odd words led to an object below the ground. Using his Knockings and insight, La Bas interpreted the “Epigram on Egyptian-American Cotton” in a way a detective with a different background and consciousness might not. He takes the anagram’s title and its three cryptic lines to mean that Hamid buried the Jes Grew Text beneath a place where people dance (“dancing bales”) and where cotton somehow figures. La Bas, with his vision that encompasses history and the popular doings of the day, can see a link between dancing and cotton. They equate to black entertainment and the legacy of black slavery. That must mean the book is below the Cotton Club, the nightclub in Harlem, and sure enough, La Bas and Black Herman go there and dig. They do not find the book, but evidence says the book was there. Sadly, Hinkle von Vampton beat them to it. He got its location from Hamid before killing him, and in a deal he cut with the Atonists in their war against Jes Grew, Hinkle then burned the book.

Besides Poe, Reed seems to be alluding to the Conan Doyle story, “The Adventure of the Dancing Men,” a mystery that involves a cipher to be decoded, and the epigram’s reference to “The Bird”, again suggests a nod to The Maltese Falcon. More explicitly than anywhere else in the novel, Reed is locating La Bas in a detective fiction tradition while making it clear that La Bas is outside that tradition. Deductive reasoning worthy of Sherlock Holmes and toughness akin to Sam Spade’s have helped him crack this case, but he would never have been able to get to the bottom of what is going on without his African-infused Neo-Hoodoo sensibility.

That Reed has drawn as well on La Bas’ black detective forbears goes without saying. He describes one character as renting “a room above “Frimbo’s Funeral Home”, an allusion to Rudolph Fisher’s Harlem Renaissance era novel, The Conjure Man Dies. Fisher’s book was the first major detective novel ever published by an African American and his investigators, the physician John Archer and the New York City police detective Perry Dart, the first black detectives in a novel. Reed does not allude directly to Chester Himes in Mumbo Jumbo, but he has written extensively about Himes, above all in his essay collection, Shrovetide in Old New Orleans. Published in 1978, years before the Himes revival began, Reed’s piece shows that he damn well understands the significance of the Harlem crime novels. He accurately predicts that “It won’t be long before Himes’s ‘Harlem Detective series,’ now dismissed by jerks as ‘potboilers,’ will receive the praise they deserve.” Among other things, the Harlem crime series, building on what Rudolph Fisher did, lay a groundwork for a black detective path in fiction. “The black tough guy as American soothsayer,” is how Gerald Early, in a review of Reed’s essay, describes what Himes unleashed, and Reed himself says in his piece that Himes “taught me the essential difference between a Black detective and Sherlock Holmes.”

GIVEN HIS POSITION IN THE WORLD AND HOW IT MAY DIFFER FROM THE POSITION OF A WHITE DETECTIVE, PROFESSIONAL OR AMATEUR, CAN A BLACK DETECTIVE RESTORE ORDER AND BALANCE IN A MYSTERY STORY IN THE WAY A WHITE DETECTIVE USUALLY DOES?

Given his position in the world and how it may differ from the position of a white detective, professional or amateur, can a black detective restore order and balance in a mystery story in the way a white detective usually does? And how about in Mumbo Jumbo, where secret societies exert power and the overall crime is so wide-reaching that restoring justice in any meaningful way seems impossible? For all the explaining Papa LaBas does, has he cleared everything up? With the Jes Grew Text burned, no one will know what it said, and the Jew Grew virus may fade away.

Reed opts for limited closure and an indeterminate conclusion. We will never know the actual words of the Jes Grew Text. It’s a frustrating ending, but not a despairing one. La Bas’ investigation has opened up a new awareness, a revisionist view of Western civilization’s wellsprings and conflicts. If the reader has been paying attention, that person will want to investigate further, become a kind of detective outside the book. It’s great that as far as Mumbo Jumbo’s murderer goes, the culprit was identified and caught, but there is plenty more to probe and reckon with beyond that.

And the Jes Grew virus itself. Will it indeed perish with its guiding text gone?

Not likely.

As Las Bas says to a younger person asking him questions:

“Jes Grew has no end and no beginning. It even precedes that little ball that exploded 1000000000s of years ago and led to what we are now. Jes Grew may even have caused the ball to explode. We will miss it for a while, but it will come back, and when it returns, we will see that it never left.”

History is cyclical, not strictly linear, and despite the struggles, the afflictions endured, the perversions of historical truth those in power disseminate, Reed’s detective remains optimistic.

Scott Adlerberg lives in Brooklyn. His first book was the Martinique-set crime novel Spiders and Flies (2012). Next came the noir/fantasy novella Jungle Horses (2014). His short fiction has appeared in various places including Thuglit, All Due Respect, and Spinetingler Magazine. Each summer, he hosts the Word for Word Reel Talks film commentary series in Manhattan. His new novel, Graveyard Love, a psychological thriller, is out now from Broken River Books.

Most detective novels tell a story about a local crime. But what about the crime stories much bigger? I don’t mean stories, say, about government corruption or drug smuggling or international human trafficking. These tales present us with crimes grave and damaging enough, but every so often, in a mystery novel, you’ll find a detective coming up against something even larger in scope. Ishmael Reed’s 1972 book, Mumbo Jumbo, provides one such example. You might say the novel’s criminal is nothing less than recorded history. Yes, history itself is the culprit in these pages, and the specific crime is the oppression, the stifling, the diminishment, of one civilization by another. It takes an unusual type of detective to investigate a case with implications so broad, and that’s where Reed’s investigator, PaPa LaBas, described as an “astro-detective”, comes in.

It’s the early 1920s, in New York City. Papa La Bas works out of Harlem, his office located in a two-story building named The Mumbo Jumbo Kathedral, and his purported strong ties to Africa are clear in how he’s introduced:

“Some say his ancestor is the long Ju Ju of Arno in eastern Nigeria, the man who would oracle, sitting in the mouth of a cave, as his clients stood below in shallow water.”