Neopagans have a great deal to teach 21st Century socialist, if only we would listen. As capitalism has gone into deep decline in the United States and England beginning in the 1970s, two spiritual movements have sprung up outside Judeo-Christianity: The New Age and Neopaganism. Contrary to some sociologists’ claims that Neopagan Wiccans, Druids and Ceremonial Magicians are not part of the New Age, I argue that there are at least 27 differences between the two. I claim that these differences could be the basis of an alliance between Neopagans and 21st Century socialists.

ORIENTATION

Beginning in the late 1970s, Yankeedom became increasingly conservative as the standard of living declined. The white working-class flocked to the more conservative fundamentalist churches where they were told to vote for a conservative in the 1980 elections. But what happened to the middle and upper middle-classes? They also experienced an economic decline. For some, their strategy was to reject organized religion, and build two alternative spiritualities: the New Age on the one hand, and Neo-Paganism on the other. This article compares and contrasts them to each to each other.

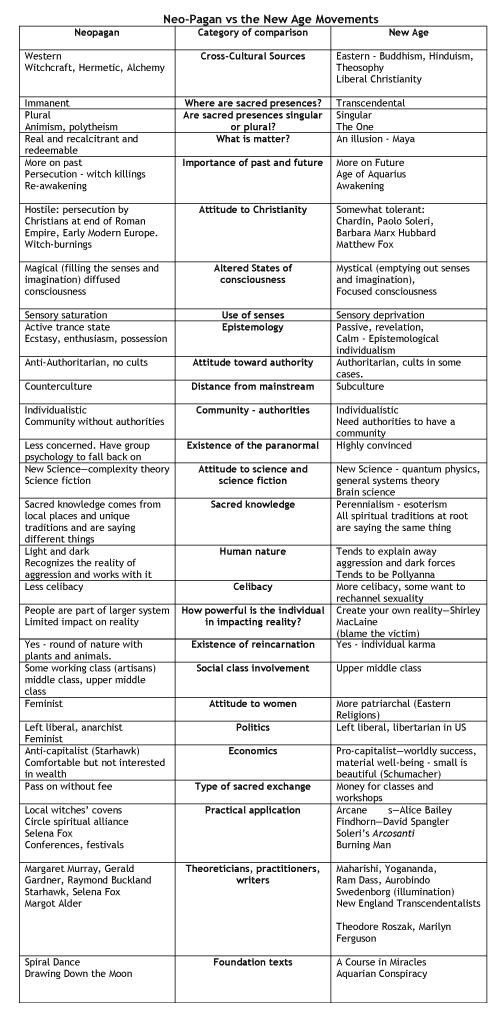

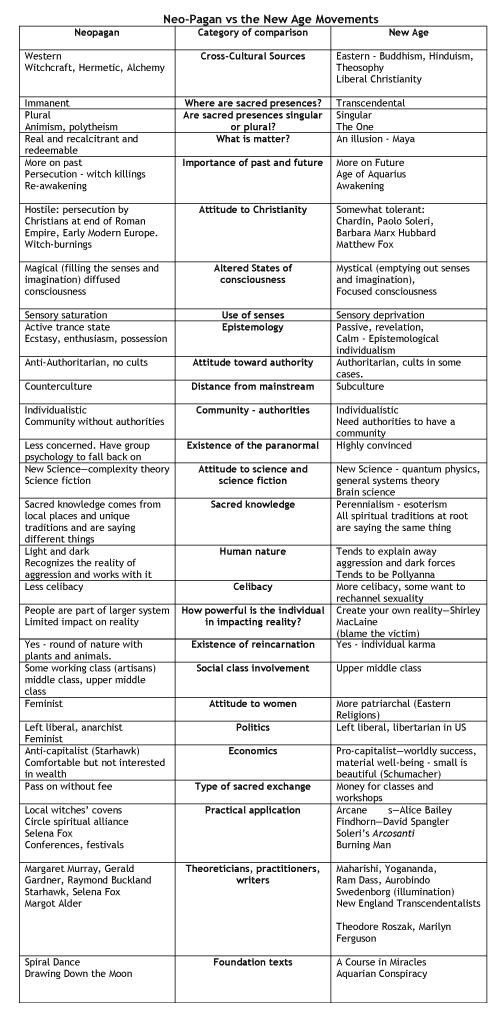

I begin the article with the economic conditions of Yankeedom between 1948 to about 1978. I then provide working definitions of each movement, when they started and who their major contributors were. I then compare and contrast the New Age and Neopaganism in depth. I begin with what they have in common, but I spend most of the article contrasting their differences across 27 categories including the importance of the past and future; attitude towards Christianity; the methods of achieving altered states of consciousness; importance of the paranormal and attitude and stance towards authority. As a materialist, my concern is also with New Age and Neopaganism’ place on the political spectrum and their attitudes towards capitalism. Lastly, I examine their class composition and their stance on feminism. I close Part I of this article by asking questions about how relevant both movements might be to 21st century socialism. In Part II of this article, I answer the questions I’ve raised.

My sources for this article are The Emerging Network: A Sociology of the New Age and Neo-Pagan Movements by Michael York, The New Age Movement by Paul Heelas, Drawing Down the Moon by Margot Adler, and The Aquarian Conspiracyby Marilyn Ferguson. I will also draw on my personal experience, having lived in and around both of these movements in the San Francisco Bay Area (jokingly referred to as the Neopagan capital of the world) between the ages of 30-50 during 1970- 1990. I also witnessed the start of the Burning Man phenomenon, which some say is the essence of the New Age.

Yankeedom Economic Roller Coasters 1950-1990

Marxian economists agree that between the end of World War II and about 1971 were the golden years of capitalism, at least in Yankeedom. Germany and Japan were decimated by the World War II and offered no competition to Yankee capitalists. The white working-class never had it better. Unions were stronger than ever (about one worker in three was in a union). The GI bill allowed these workers to buy cheap homes in the newly built suburbs and go to college tuition-free if they wanted. The Yankee rulers were so wealthy that they were taxed up to 90% of their earnings and they still made great profits. A working-class family lived comfortably on one income and the job, on average, was 40 hours a week. Under these abundant conditions, it is no accident that there were no New Age or Neopagan movements because movements are more likely to emerge when economic, political or ecological conditions are difficult.

Economically, things began heading south in the early 1970s. Germany and Japan had recovered from the war and were beginning to compete with Yankee capitalists. One response from the Yankee rulers, rather than competing directly with these two nations, was to rip off more surplus value from workers. Yankee capitalists uprooted manufacturing jobs and set up factories in what were then called “Third World” countries where land and labor were cheaper. These were called “runaway shops”. This meant the end of well-paying manufacturing jobs for workers. Unions were not strong enough to stop this. No retraining was provided by the state, as workers had to scramble to find semi-skilled or unskilled jobs. The second way Yankee capitalists squeezed surplus value out of workers was to increase the number of hours workers labored during the week and the number of hours worked each day. By the 1980s, the average work week had risen from 40 to 50 hours per week and working-class and middle-class households required two incomes. Workers struggled with insecure jobs and the unions were unable to protect workers’ health-care benefits. Workers began to lose confidence in unions and union membership declined.

A third major decision the ruling-class made was to invest their money in financial capital rather than industrial capital. In 1971 the rulers decided to go off the gold standard as the reserve currency and the dollar had no gold backing. Capital could be exchanged by bankers without needing gold to back it up. In addition, the United States had lost in Vietnam and the oil embargo by the OPEC countries sent a shiver down the spines of the Rockefellers. The Rockefeller sponsored Club of Rome project told the Yankee population that population pressure was a real problem and people needed to live on less. Yankeedom was in economic decline. By the late 1970s Jimmy Carter was telling its population that we needed to learn to do with less.

All this is not the kind of news the Yankee population expected to hear. Increasingly, politicians were distrusted while the mainstream religions were seen by both middle-class and upper middle-class sectors of the population as part of the problem. It is in these declining conditions that the Neopagan and the New Age movements should be understood. Both alternatives were optimist spiritual reactions to a depressed state of the political economy and mainstream religion.

What Does the New Age and Neopaganism Have in Common?

Before we define the New Age and Neopaganism, let’s begin by what they have in common. Though the seeds of these movements are difficult to pin down, the time of their clear presence was remarkably similar. Neopaganism “arrived” in 1979 with the simultaneous publishing of two books: Starhawk’s The Spiral Dance and Margot Alder’s book Drawing Down the Moon. For the New Age, the founding text, the Aquarian Conspiracy by Marilyn Ferguson was published in 1980.

Both movements were strongly motivated by a rejection of mainstream Judeo-Christian religion. Both movements believed in the power of personal experience, whether magical or mystical, as opposed to trusting religious authorities, whether they be priests or rabbis. Each believed that every individual had a “higher self” that superseded the ego. The experience of novices of both Neopagan and New Age movements when they first find out about the movements is mostly described as a “homecoming”. There are no reports of conversion. Both agree that evil not an objective force (as in the form of a devil). Rather, each think that evil has either a psychological or social origin. Neither intends to grow bigger, as there are no Neopagan or New Age missionaries. Each is life-affirming and optimistic rather than life-denying and pessimistic.

Each movement was decentralized, consisted of word-of-mouth, grapevines and networking. Neither movement has a national central organization. Neopagans are militantly against centralization and Wiccan covens closely resemble anarchist organizations. New Agers’ interests span a larger number of disciplines and the whole movement is more of an eclectic mishmash with no center. Partly for these reasons, the precise number of people in each movement is hard to pin down. Both movements are located in the United States and, to a lesser extent in England. Both are critical of depicting change in a gradual, linear and inevitable way. Each sees change as happening in cycles, and when something new emerges it is the product of non-linear dynamics.

Summarizing the Commonalities:

- Point of origin: late 1970s

- Place: United States, England

- Economic conditions: decline of industrial to finance capital

- Religion: Rejection of Judeo-Christianity

- Authority: Distrust of religious, political and scientific authorities: value of personal experience

- Type of self: higher self (Jung) atman self (Hinduism)

- Outlook: optimistic

- No need for conversion or proselytizing

- No devils (evil is psychological or social)

- Organization: decentralized

- The shape of time: Both see the limits of linear time. Each sees change as happening in cycles, spirals and in non-linear ways.

Defining the New Age

Why Aquarian?

Many consider the book The Aquarian Conspiracy to be the “bible” of the New Age Movement. The title of the book locates the New Age within an astrological framework. Supposedly, we are coming out of the darker side of Age of Pisces, the age of spiritual decline, into the Age of Aquarius. Astrologically the Aquarian Age means the age of experimentation, innovation, light, healing and love. In what areas do we see these characteristics operating?

Ferguson tells us the spirit is operating in many fields: brain science and consciousness studies; the new science of general systems theory and physics; medical health with alternative medicine; in education and spirituality. The problem here is that by calling this movement, “Aquarian” or even “New Age”, gathers people in these fields under an astrological umbrella. Some of schools of thought listed such as the complexity theory of Prigogine, the General Systems theory of von Bertalanffy or the philosopher of science, Thomas Kuhn would hardly be happy with astrological associations. Neither would Ferguson’s heroes L. L. Whyte, Jan Smuts (Holism and Evolution), Alfred North Whitehead or Gregory Bateson. Let’s accept this unfortunate start and let’s say she is on to something regardless of its astrological associations.

Who are its heroes and heroines?

Besides those mentioned above, who are the rest of Ferguson’s New Age heroes? In history we have Toynbee, De Tocqueville, and William Irving Thompson. In education, A.S Neill and Ivan Illich; in the globalization of society there is Marshall McLuhan, Teilhard de Chardin, Willis Harman, and H.G. Wells. In brain science there is Karl Pribram, in physics Fritjof Capra (The Tao of Physics) and David Bohm. Mystics of many ages are claimed as predecessors – Meister Eckhart, Jacob Bohme, Pico and William Blake, and closer to the present, the New England transcendentalists William James (Varieties of Religious Experience) and Bucke (Cosmic Consciousness). There are two humanistic astrologers who were especially important to the New Age: Dane Rudyhar and Marc Edmund Jones. Mythologists like Joseph Campbell and psycho-mythologists like Jung were enormously popular.

Very important to the New Age was the work of Ken Wilbur and Jeanne Houston. Wilbur’s first book The Spectrum of Consciousness created a continuum link between psychology and spirituality. From there he went on to write spiritual books on social evolution (Up From Eden) and developmental psychology (Atman Project). Jean Houston also straddled the line between psychology and spirituality with what she coined “Sacred Psychology”. She wrote books which showed how Greek mythology could be used for psychological growth. Her book Life Force described the history of the West based on five stages of self-development. These stages were based on the work of Gerald Heard. In the field secular psychology, the humanistic psychologists Maslow and Rogers, Rollo May and Erich Fromm were part of the human potential movement, not the New Age. But some of these humanistic psychologists were also interested in LSD and were influenced by Aldous Huxley and later by Stanislav Grof along with the popular shamanism of Carlos Castaneda.

Down with mechanistic, reductionist science!

The New Age is not just rebelling against organized religion. It is also reacting to conventional science with its overspecialization. This overspecialization keeps traditional science from seeing the big picture and having an interdisciplinary perspective. New Agers complain about mainstream’s sciences tendency to reduce all complexity in nature to physics. It also rejects dualism involving separation of mind from matter and mind from body. It believes modern science is slow, plodding and preoccupied with gradually building things up. What this misses is that nature is full of surprises and qualitative leaps whether in scientific knowledge (Kuhn), physics (Bohm), the nature of subatomic participles (Capra), or biology (Gould’s punctuated equilibrium). Change often does not happen in a linear way but in a non-linear manner as described by Prigogine. Lastly, conventional science sees nature as mechanistic and driven by external forces, rather than organic and self-regulating (Von Bertalanffy, general systems theory.)

Sharpening the boundaries of the New Age

One problem with the New Age is its fuzzy, overly inclusive boundaries. For example, its inclusion of the human potential movement within it. When we look at the practice of the human potential movement, the psychological boundaries of individuals were pushed much more aggressively than most of the practitioners of the New Age would be comfortable (with the exception of “Guru” groups like EST of Rajneesh). Secondly, the use of hallucinogenics in the early 70s had no official approval and the psychologists were treating those who came to Esalen as human experiments. Fritz Perls and Will Schutz got into raging fights. Perls slept with many of the participants at Esalen and took enjoyment in reducing them to tears. Many of the group therapy sessions were done in the nude with no structure, explanations or reasons. Group marathons were held all weekend, “opening people up”, without offering any follow-up support. This method is hardly about bringing love and light to people that New Agers advocate.

The Human Potential Movement was primarily psychological with spirituality on the periphery. Yes, I remember books by Alan Watts and Dameon on the coffee table of hippie friends in Berkeley in 1970, but they were more the exception than the rule. The New Age was primarily spiritual with psychology on the periphery. Lastly, the New Age was much more supportive of petit bourgeois capitalism, whether it be small shops or decentralized economies (Small is Beautiful). The Human Potential movement was generally silent about capitalism.

Defining Neopaganism

“Monotheism is but imperialism in religion” – James Breasted

It is also significant that one group that Marilyn Ferguson never mentions as exemplars of New Age were Neopagans. The reasons for this will be clearer later on in this article, but for now it is just worth mentioning.

Roots of Neopaganism

Neopagnism clearly came of age in the late 1970s and has grown since then. But how far back does it go? In terms of the Wicca tradition, there was the work of Gerald Gardner in the 1940s. However, in terms of ceremonial magick, Neopaganism goes back to the 19th century with the Golden Dawn. But ceremonial magic has a long history itself going further back to the Renaissance magick of Ficino, Bruno and Paracelsus. The term “Neopagan” really refers to pagan practices since Gerald Gardiner reconstructed wiccan ritual practices.

Types of Neopagans

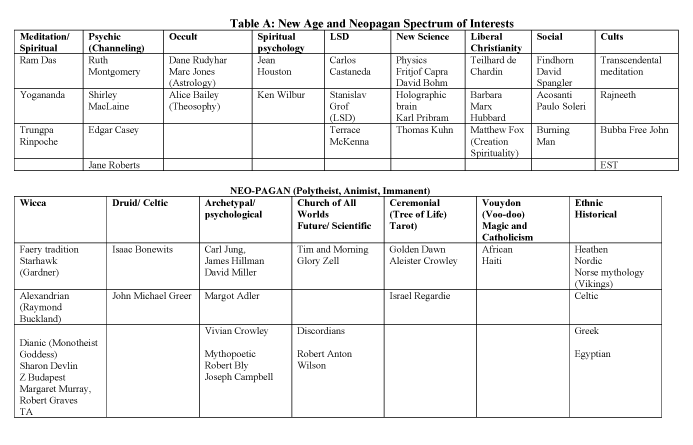

Like the New Age, Neopagans exist on a spectrum.

- Gardnerian Wicca which originated in England and was the first reconstructed wicca which drew from Margaret Murray and Robert Graves

- Alexandrian Wicca which also originated in England and more than other wiccas, has hierarchical grades and tests that must be passed to advance

- Dianic Wicca focuses on a single goddess and consists of virtually all women covens. They also draw from Margaret Murray. Z Budapest is a famous example.

- Faery Wicca specifically working with nature spirits. Gay men have been influential. Starhawk’s group Reclaiming is part of this.

- Ethnic/historical Neopagans aim to revive pre-Christian practices of the Greeks, Romans, Druids, Celtic and Norse traditions.

- Voudon – these practices developed in Africa and Haiti, combining magic with Catholicism. It used to be called Voo-doo.

- Ceremonial magic which draws from the Golden Dawn and the work of Aleister Crowley. Ceremonial magicians tend to synthesize systems such as The Tree of Life, the Tarot and Astrology.

- Neopagans who emphasize the future based on science fiction writers. The Church of All Worlds is an example of this.

- Jungian archetypal psychology. While Jungians are not themselves a type of Neopaganism, there are Jungian interpretations of what wiccans and ceremonial magicians are up to. Besides Jung, James Hillman’s polytheistic psychology and the work of David Miller have done a great deal to make paganism respectable in the eyes of psychologists. Margot Adler has brought a Jungian perspective to the history of Neopaganism. Vivianne Crowley has done the same in England. Robert Bly has added a mythopoetic slant to involving more men in “men’s mystery traditions”.

Who does Neopaganism exclude? Excluded are most Eastern mystical groups with an authoritarian structure, Christianity and Satanism, which most Neopagans consider reversed Christianity.

Characteristics of Neopagans

Though there are significant differences between Neopagan groups, they do share the following characteristics:

- The sacred sources are plural. There is a belief in animism, polytheism or pantheism. There is one exception to this and that is some feminist wiccans insist on revering a single monotheistic Goddess. Recently there has developed paganism without gods and goddesses. Mark Green has developed something called “atheopaganism” and John Halstead has cultivated something he calls “humanistic paganism.”

- The sacred sources are immanent, not transcendent. This means that the material world is self-regulating and does not require intervention. Nature is all we need.

- Like the material world, the human body is not in a fallen state. The senses and sexuality are celebrated, not depreciated.

- The method of altering states of consciousness is through a collective ritual in which the imagination and senses are saturated through the arts, using music song, dance, incense, and mask-making. This is called the art and science of magick.

- Neopagans are generally anti-authoritarian and do not accept revealed sacred knowledge. Magical practices are experiential.

- There is a practice which is connected with the celebration of eight pagan holidays throughout the year. Rituals are also done for special occasions like coming of age, marriages and death.

Who are Neopagan Heroes and Heroines?

Besides Gerald Gardner, some of recent figures associated with Neopaganism are Margaret Murray, Robert Graves, James Frazer. Theoreticians are Isaac Bonewits, Aidan Kelly and Starhawk. Other notorieties include Z Budapest, Morgan McFarland, Selena Fox, Tim and Morning Glory Zell-Ravenheart and Gwydion Pendderewen.

Comparing the New Age to Neopaganism

I will now systematically compare New Agers to Neopagans across 27 categories. Please peruse the table to get a handle on where we are going.

Time, place and ontology

The first major difference has to do with ontology. New Agers draw mostly from Eastern traditions: Buddhism, Hinduism and the Theosophy of Blavatsky and Alice Bailey. Neopagans draw from the Western tradition of witchcraft, hermeticism and alchemy. Closely connected to this are the differences in the attitude towards matter.

New Agers follow Eastern traditions that say that matter is an illusion at worst, derivative of spirit at best. Neopagans treat matter as real, recalcitrant and to be struggled with. Western alchemists saw that their work was to “redeem matter” by changing sulphur, salt and mercury into gold. For New Agers the universe is one and transcendental to the material world. As I said earlier, with the exception of some female wiccan goddess worshipers, all Neopagans speak of nature as plural. They are either polytheists or animists and they believe these powers are immanent. Nature is self-creating and self-regulating. Lastly, New Agers follow Huxley’s perennialism which says that all the world religion have esoteric core claims which are the same around the world. The differences between religions are exoteric, superficial, superstitious, and decadent. For Neopagans, sacred knowledge comes from local places which are unique to it and cannot be joined with others without the tradition being watered down or lost.

New Agers do not spend much time analyzing the past. They believe that ancient societies were wiser and contained spiritual wisdom that was lost with the Age of Pisces. What matters is that we are living in the present and the long-distant future in the Age of Aquarius. The New Agers have no axe to grind with the past. This is not so with Neopagans, as we shall see next.

Attitudes towards Christianity

Neopagans are very aware of what Christians did to pagans at the end of the Roman Empire. The brutal killing of Hypatia and the burning of the Alexandrian library is just the tip of the iceberg. In the Renaissance, pagans had to hide their magical practices. The centralized state, along with the Protestants and Catholics, persecuted the witches in Early Modern Europe. Pagans for the most part are anti-Christians, and even today have to worry about being persecuted. Many Neopagans neither forgive nor forget.

New Agers are much more likely to be eclectic and incorporate Christianity. For example, in response to Marilyn Ferguson’s questionnaire, the Christian paleontologist Teilhard de Chardin was named as their greatest inspiration. Barbara Marx Hubbard’s book Conscious Evolution is modelled on Chardin’s work. Paolo Soleri’s building of “Asrcosanti” in central Arizona has been inspired by Chardin. Furthermore, New Agers have welcomed Dominican Catholic priest Matthew Fox into the fold. Fox’s Creation Spirituality even made room for wiccan Starhawk on his teaching staff.

Attitudes to authority, community, subculture and countercultures

The wiccan tradition was visited by a passing comet, during the radical wing of the women’s liberation movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Some women were not satisfied with promises of the patriarchal churches to reform and they searched for a women’s spirituality beyond all organized religion. They found it in wicca. These women carried the same leveling tendency into wicca that they carried with them into the New Left. They met little resistance from wiccan covens that were already established. Neopagan communities generally consist of many people who are self-educated and are hostile to most authorities. The culture that they create is a strong counterculture which consists of covens, bookstores, coffeehouses in cities, and self-sustaining farms in rural areas. These are countercultures which are in conscious opposition to the dominant culture. While pagans can be very individualist, most of their practice is community-based.

New Agers have had less of a history of persecution and are far less afraid of being harassed by mainstream religious authorities. They are more respectful of authorities (especially Eastern teachers) and are much more likely to be victims of cults. There is a New Age culture that can be seen at talks, conferences or festivals, but it is not built out of necessity and it is much more loosely formed. New Agers are more at home with structured authorities and do not have communities which gather together to create a New Age experience. As we shall see, most New Agers come out of professional settings, are more individualistic and less experienced in creating a community independent of the authorities.

Drug-induced mystical vs magical states of consciousness

Hallucinogens have been important in New Age Culture, going all the way back to Huxley’s use of mescaline. Psychologist Stanislav Grof has studied and advocated for LSD and Terence McKenna has argued for the power of hallucinogenics in tribal societies. Setting aside the issue of drugs, an altered state of consciousness can be achieved in two ways. One is through sensory deprivation, which can create a mystical experience. The other, sensory saturation, creates a magical state of consciousness. For New Agers, since their major influences have been Eastern, various forms of meditation have been the road to a spiritual state of mind. While Neopagans may use meditation as an initial starting point to ground themselves at the beginning of a ritual, the ritual itself is not meditative. The use of drumming, singing, dancing, colorful costumes, incense, and food saturate the senses to create enthusiasm or ecstasy. This is an active, trance state in which the participate “travels” or in some cases is possessed. Mystical states create calm, passive revelation. Magical states create controlled pandemonium – where all the gods speak.

Paranormal, archetypes and supernaturalism

Marilyn Ferguson’s questionnaire for New Agers indicated that there was very high belief in ESP, clairvoyance and telepathy (85%- 94%). Margot Alder gave no corresponding results for Neopagans, but it is safe to say a large number of Neopagans also believe in paranormal phenomenon. However, there are two important differences. There are more Neopagans who not only are interested in the new sciences, but are more skeptical and willing to criticize them from a knowledge of scientific methodology. New Agers, in my experience, are more likely to commit to the confirmation bias and not look for evidence that contradicts what they already believe.

The second important difference about belief in the paranormal is that Neopagans have seasonal rituals in which they have positive group experience on a repeated basis. They are aware that the social group has the power to alter their state of consciousness. They have less need to believe in paranormal experiences in order feel connected. In addition, many Neopagans do not even believe in the independent existance of goddesses or gods. Some think they are Jungian archetypes which are the product of humanity, not a spiritual world.

Human nature and individual power

Since New Agers tend to see matter as an illusion, it seems hardly far-fetched to think they see dark and negative forces as products of short-sightedness, ignorance or egotism, but in no sense real. This has led to them being called pollyannish, seeing the world through rose colored glasses. The spiritual power that comes with enlightenment is so powerful that it is thought that individuals create their own reality (as Shirley MacLaine has argued).

Just as Neopagans see matter as real and recalcitrant, they also understand forces that are considered dark as real and which are much deeper than short-sightedness or egotism. Neopagans might draw on evolutionary psychology, specifically sexual selection to explain conflicts between males and females. So too, they might explain conflicts as evolutionary mismatches between the conditions under which we formed our human nature (hunter-gatherers) and our contemporary industrial capitalist societies, which are far from those conditions. What follows is that for Neopagans neither individuals or groups “create their own reality”. We are limited in what we can achieve as both the biophysical world and the socio-historical worlds are larger systems and cannot be pacified or reduced to background.

Politics and Economics

In her book The Aquarian Conspiracy, Marilyn Ferguson claims that politically New Agers constitute a “radical center”, a combination of Republicans and Democrats. But there is no New Age consensus about this. There really are no conservative New Agers. There seem to be a combination of New Deal liberals or they are libertarians. Neopagans are much broader politically. There is a strong anarchist presence in the work of Starhawk and Reclaiming, and Reclaiming groups have spread from the SanFrancisco Bay Area to other parts of the contrary. In addition, Neopagans seem to be New Deal liberals, but there are also two more right-wing elements. The Heathen Nordic tradition in the United States has more patriarchal elements and has been accused by other Neopagans as fascist. In Europe, some Neopagans who are part of the ceremonial Magick traditions such as the Golden Dawn are reactionaries or even monarchists (Dolores Ashcraft-Nowicki). Ceremonial Magick have orders with graded hierarchies. It makes sense that if their orders are hierarchical it is a reflection of their beliefs about human political systems.

The New Agers are not bashful about thinking there is nothing wrong with material success. (Heelas, New Age Movement 58-67). Neither do they seem to worry that the cost of their workshops and lectures might be beyond the financial reach of working-class or poor people. In the index of The Aquarian Conspiracy there is no entry about either capitalism or socialism. What this means to me is that economics is not thought of in a systematic way, as in calling it “capitalism”. Rather, it is seen as “the economy”. It seems to have never crossed their minds that they might be promoting a spiritual capitalism. Neopagans are very critical of the New Age leaders charging large sums of money for what spiritual knowledge they have to offer.

Traditionally in wicca, the “Craft” is passed down without charge. The important thing is that the aspiring student be serious, do the work, be consistent in attendance and pass on what has been learned in the same spirit in which it was given – for free.

Wiccans are the most likely of Neopagans to be anti-capitalist. Some, like Z Budapest envision a socialist matriarchy.

Gender and class

In Marilyn Ferguson’s questionnaire, she said that the most of her sample were professionals (meaning upper middle-class) there is no representation of working-class people. In addition, to the extent that the New Age supports Eastern traditions such as Buddhism, Hinduism or Zen, they buy into an Eastern patriarchal framework.

The presence of cults that often comes out of these traditions and guarantees there will be extreme dominance by a leader which, in cults, is almost inevitably a male.

In her book Drawing Down the Moon, Margot Adler says that some of the first witches she meet in England were working-class. To the extent that wiccans own farms they work on, they are likely to be what Marx called petite bourgeois. Usually, rural pagans do all the work on the farm themselves, including blacksmithing, tanning, weaving and selling to a market. There are also middle-class and upper-middle class Neopagans. The number one profession for Neopagans on Adler’s survey were computer programmer, systems analyst or software developer. But third on her list is secretary or clerical, indicating membership in white collar working-class. There are middle-class and upper middle-class workers such as teachers or therapists but the percentage of upper middle-class is lower than for New Agers. Lastly, Neopagans are extremely supportive of feminism. Some Dianic witches don’t even allow men in their covens. The structure of wicca gives more weight to goddesses than gods and it has been an adjustment for male wiccans not to be centered in these rituals. Generally, wiccan men are very supportive and the presence of gay men in the rituals has helped feminism.

Practical Application

New Age communities can be seen in three applications. The first is Burning Man which began in 1986 has lasted into the present. This is a yearly creative gathering that began in San Francisco and then moved to Black Rock, Nevada. In my opinion this gathering draws young, upper-middle class people who are disappointed they missed the 1960s and want to make up for that period. In recent years it has been attended by wealthy people whom some complain have not respected the principle of self-reliance. It has gotten more and more expensive to attend. Some say the role-playing and self-expression are more signs of narcissism and capitalist decadence than model communities of the future.

Another New Age community project is one started by Italian city planner and follower of Teilhard de Chardin, Paolo Soleri . His project(started in 1970) is to build an urban environment which encourages intense social interaction in the absence of large-scale industry and built with ecologically sensitivity. It has been worked on for 40 years, with an ideal of housing 5,000 people. Findhorn Foundation, an intentional village community located in Scotland, has been developing since the 1980s. The community is based on the theosophical principles of Alice Bailey.

Neopagans are less interested in large scale intentional communities. In witchcraft, the basic unit is the coven. The coven usually consists of between 8 and 13 people who meet at a minimum of eight times a year to celebrate and ritualize the eight pagan holidays of the year. Some are more ambitious and meet to celebrate coming of age rituals, marriages or funerals of individual members. There has been a growth in recent years of Neopagan regional conferences and festivals.

Prospect: Is It Possible to Synthesize Socialism with the New Age and Neopaganism?

Towards the beginning of this Chapter, I identified commonalities between the New Age and Neopaganism. I will selectively use some commonalities to pose some questions. Both Neopagans and New Agers reject mainstream Judeo-Christianity. Would this help or hinder the development of socialism? Most socialist theoreticians claim to be atheists, so they would agree with rejecting Judeo-Christiantiy. However, they would not want to replace it with Eastern mysticism or gods and goddesses. But what about with possible recruits from the working-class, many of whom may be fundamentalists? Both Neopagans and New Agers reject religious, political and scientific authorities and trust their own experience. What would the working class think of this? The organization of both New Agers and Neopaganism is decentralized. Will that organization help or hurt the development of socialism?

We said the outlook of both movements is optimistic. Will this optimism help or hinder the building of socialism? Both Neopagans and New Agers claim that human beings have a higher identity than the ego. Each claim to have a “higher” self that is capable of tapping into a deeper reality. Will this new identity be welcomed or mocked by socialists? Unlike mainstream religions, neither New Agers nor Neopagans claim they are missionaries and say they are not in the business of conversion. Given that historically socialists have tried to convert the working class, this lack of missionary zeal will not set so well with socialist theoreticians. Neither Neopagans or New Agers personify or objectify evil. Given socialists’ claim that capitalism is the root of all social problems, do socialists personify capitalists as evil? If so, does this mean socialism loses its edge if it stops proselytizing? Both Neopagans and New Agers reject linear concepts of time, for cyclic and non-linear time frames. This would seem to go very well with the Marxian dialectical shape of history.

In Part II of this article, I will discuss how each taken separately can be useful or not useful to socialism. In this section, I will only use the categories of comparison in order to pose but not answer more questions. New Agers are drawn to Eastern traditions and Neopagans to the West. Should that matter to socialists, and if so, why? Should it matter to socialists whether Neopagans or New Agers understand nature as a single force or plurality of forces? Should it matter to socialists if nature is understood as both self-creating and self-sustaining or whether there is a force beyond nature? Is matter real and independent of consciousness or is matter an illusion and only consciousness is real? Why should this matter to socialists?

Both New Agers and Neopagans emphasize the importance of creating altered states of consciousness, with drugs or by sensory deprivation or sensory saturation techniques. Does this get in the way of building socialism or can it advance it? Neopagans are further away from mainstream culture than New Agers. Can this assist or hinder socialist attempts or organize and sustain socialist organizations. Many New Agers are convinced that paranormal psychology is real and that we must cultivate those skills. How will this be received by socialist theoreticians and socialist recruites from the working class?

Both movements reject reductionist science for the new, non-linear science in the fields of physics, and the brain. Will socialists jump on this bandwagon or dismiss this science as pseudo-science? How will socialists greet the New Age notion that people are good and only turn our badly because they are uneducated, ignorant, short-sighted. Will they agree with Neopagan characterizations of the New Age as Pollyanna.

Freedom is highly valued by both New Agers and Neopagans. But is there such a thing as going too far? How will it go over with working-class people when Shirley MacLaine tells each working-class individual that they “create their own reality”? Some New Agers claim to believe in reincarnation. Some say individuals are working out karma based on past lives. What will this do to socialist organizing. How might it help a working-class person to know they were a prince or a pauper in another life? The class composition of New Agers is primarily upper-middle class. How easy will it be for socialists to integrate them into a socialist organization. Many wiccans are organized into covens. Will that organization help or get in the way of building a socialist mass party? New Agers are more hierarchical than Neopagans and they are more likely to accept a spiritual leader, who is most of the time, a man. How will this be received by socialists?

Many women into feminist wicca are anarchists. How will this work with a socialist party organized along Leninist lines? Some New Agers are libertarian and commercial capitalists. Do these folks have any redeeming value for socialists? If a radical socialist union were taken on a tour or Findhorn, Soleri’s Arcosanti city, or an admission to a nine-day Burning Man, what would they think? What would it be like for the same group to be invited to one of the Spiral Dance rituals of Starhawk’s organization, Reclaiming? We will address and provide answers to these questions in Part II of this article.

NEW AGERS VS NEOPAGANS: CAN EITHER BE SALVAGED FOR SOCIALISM? PART II

BY BRUCE LERRO / PERSPECTIVES / 09 NOV 2021

Orientation

The term “New Age “means different things to different people: some positive, some negative. But I disagree with those sociologists or scholars of New Religious Movements who are overly inclusive and lump all kinds of alternative movements into New Age. To address this, in Part I of this article I contrasted twenty-seven ways in which Neopagans differ from New Agers. I began with what New Agers have in common. Then I defined the New Age, its boundaries and relationships with other movements along with its heroes and heroines. Then I did the same for Neopaganism. I also identified the historical and economic circumstances in which each arose.

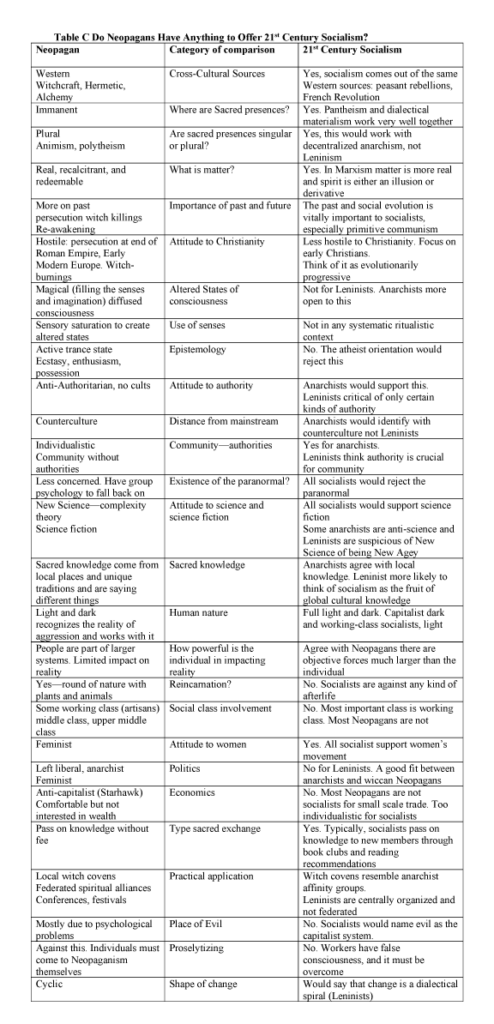

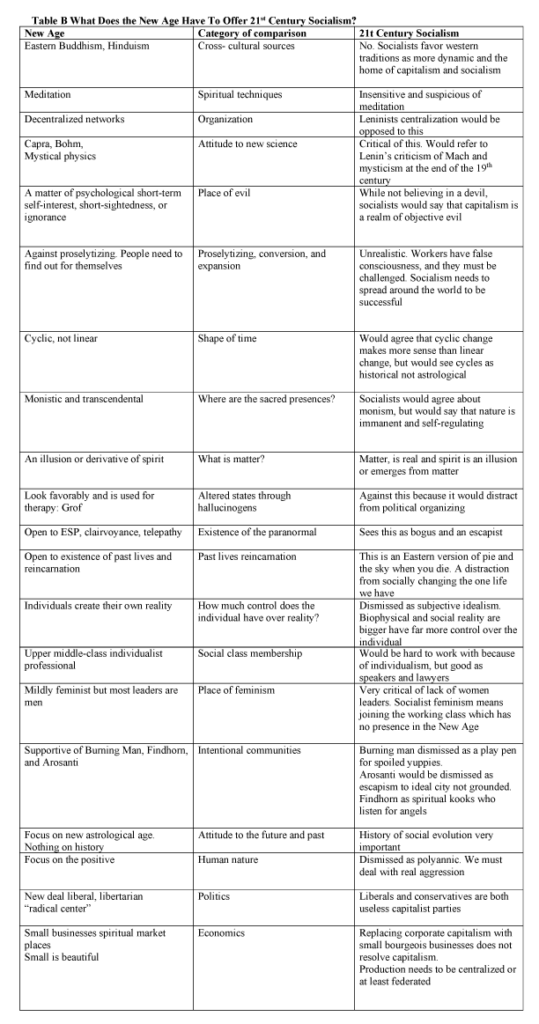

However, my intentions are more ambitious than just doing a compare and contrast exercise. As a socialist, I want to know if either the New Age or Neopagan movements have anything to offer 21st century socialism? If you ask socialists themselves the overwhelming majority say no! They might say New Age is a desperate attempt by alienated middle classes to escape the crisis in capitalism by retreating into mysticism. They might refer to its commonalities with the mysticism of the end of the 19th century that Lenin criticized. As for Neopagans, socialists might say they are a throwback to superstitious times before the Enlightenment. The Enlightenment, after all, dismissed witches as products of the sick minds of the Inquisition. Undeterred by this socialist cynicism, in Part II of this article I answer the questions I raised at the end of Part I. First, I address what New Age has to offer socialism. Then I ask is there anything of value that Neopaganism has to offer socialists. I conclude that there is almost no New Age claims and values that are of any use to socialism. On the other hand, there is quite a bit that Neopaganism has to offer socialism if only socialists would listen.

WHAT DOES THE NEW AGE HAVE TO OFFER SOCIALISM?

Eastern spiritualism and spiritual individualism

Many socialists are insensitive to the difference between the Judeo-Christian religion of the West and Eastern spiritualism, which is embraced by New Agers. They are likely to dismiss the new-found techniques of meditation and rarely meditate themselves. What socialists would particularly reject is the do-it-yourself individualist spirituality. Liberation Theology socialists might say at least Catholic spirituality has a social component. Working-class socialists would either continue with their traditional religions or simply drop out and be apathetic to their religion. Individualist spirituality would have no draw for them.

The new science and decentralized eclecticism

Socialists would happily agree with New Agers who rejected mainstream political and religious authorities, but they are not likely to agree with New Agers about science. For socialists, science is a bedrock and they are likely to be unaware of new science and would not be very interested in challenging tradition. There are some socialists that would celebrate Stephen J. Gould’s punctuated equilibrium as the application of dialectics to Darwinian theory. However, New Age interest in science is usually the New Physics, the study of the brain and states of consciousness. Socialists usually aren’t interested in these subjects. New Age is a decentralized association of groups that have made little, if any, attempt to centralize or coordinate their activities let alone centralize so that they might fight for power. Socialist would see New Age as a spiritual marketplace.

The subjective nature of evil, anti-proselytizing

The New Ager’s pollyanna attitude of love and light would drive all socialists crazy. While socialists would agree with New Agers that there is no objective evil in the form of a devil, socialists would disagree that evil comes from psychological short-sightedness, lack of education, or ignorance. Socialists would say capitalists are a small class of people that are willing to destroy humanity and the planet. This class struggle is not a matter of capitalists being short-sighted, lost, greedy, or incompetent. Socialists would not call capitalists “evil” because of its moral and spiritual overtones. But this is what it amounts to.

Some socialists would agree that the development of a socialist individual identity would move beyond the individual ego, but would say that deeper individual self is inseparable from the practice of a community of socialists and not to be achieved through an isolated spiritual practice. New Agers reluctance to proselytize or do a kind “missionary” work would be treated as lacking ambition. Socialists want to recruit the working class to its ranks and understands that the working-class has “false-consciousness” that must be overcome through argument and struggle. Socialists know that socialism can only be successful if it can spread internationally. It must aspire to expand. It cannot afford to wait for workers to get on board on their own accord.

The shape of change

Socialists would agree with New Agers that operating with a linear sense of time is outdated. They would agree up to a point with New Agers about the importance of looking at long-term change as cyclic. However, socialists’ interest in cycles would be limited to historical change. It would mock New Age interest in long-term astrological cycles. For socialists, astrology has nothing to do with what happens in history. Lastly, for Marxian socialists, cycles change into a dialectical spiral moving from theses-antithesis and synthesis.

Ancient Wisdom of the East

Is it in some way advantageous for socialists that New Agers draw heavily from Eastern traditions of Buddhism, Hinduism, and Taoism rather than western traditions in Europe? For better or worse, for socialists it would be a disadvantage. Capitalism developed first in the West and working-class opposition to it also derived there. Most socialists still believe that any hopes for socialism will come out of Europe, because there has been a much deeper history of rebellions and revolutions than in the East. The fact that the first socialist revolution (Russia) did not have advanced industry;

The fact that today the largest socialist country in the world (China) is not from the West, should make socialists pause. Unfortunately, many socialists treat Marx’s theory that socialism is most likely to be from industrialized countries dogmatically and will be slow to change.

Where do sacred sources come from: the perennial philosophy

New Agers are critical of organized religion not because the spiritual world doesn’t exist but because organized religion is a bastardized, exoteric version of religion for controlling the masses. For New Agers, at the core of every world religion is an esoteric core of spiritual truths which all the great spiritual founders agreed with. This has been called “the perennial philosophy”. New Agers support the esoteric version of all the world’s religions. What would socialists think of this? They would be happy to see that New Agers are sensitive to the propagandist nature of world religions. The less dogmatically atheists like social democratic socialists might see some value in this.

Transcendentalism, monism, and the reality of matter

New Agers tend to see an ultimate spiritual force as being monistic and transcendental to biophysical and social reality. How might that be received? Socialists will be split on the question of whether the ultimate source is singular or plural. Most Marxists are materialistic monists and they will appreciate all of reality comes from a single source. The anarchists, being decentralists will object and claim this as some form of spiritual imperialism. However, both Marxist and anarchists would be dead set against the sacred source being beyond the world (that is, transcendental). All socialists see nature and society as immanent, self-regulating, and creative. The fact that most New Agers see matter as either an illusion or a derivative of spirit would be dismissed by socialists. Socialists are generally materialists who think that matter is real and spirit is either an illusion or derivative.

Altered states, parapsychology, reincarnation, and creating your own reality

New Agers are greatly drawn to altered states of consciousness, either through mystical experience of through the use of hallucinogens. How will this go over with socialists? Not well. The leaders might think taking mind-altering drugs is a distraction from doing political work. Socialists will roll their eyes at New Age interest in ESP, clairvoyance, and telepathy and claim that a century’s worth of research has not found anything significant. They see this as more New Age escapism. Working-class recruits will find this interesting and would probably enjoy TV shows like The X-files. Some New Agers claim to believe in reincarnation. Some say individuals are working out karma based on past lives. What will this do to socialist organizing? How might it help or hurt a working-class person to know they were a prince or a pauper in another life? Socialists will view belief in reincarnation as more pie in the sky when you die. It is a distraction from the one life we have and it pulls us away from making the world a better place. It reduces our world to a reform school for learning spiritual lessons.

More extreme New Agers like EST or Shirley MacLaine claim that individuals create their own reality and that reality has no objective existence. All socialists would throw up their hands at this and point to Berkeley or Fichte and say this is subjective idealist narcissism. The objective world is prior to, independent of, and beyond subjective reality, and individuals are limited in their aspirations based on their class location, their race, their gender, and the point in history they are born.

Upper-middle class and mildly patriarchal

Demographically New Agers are primarily upper-middle class professionals. This would work against organizing them into socialist organizations or a mass party because upper-middle class people are more individualistic based on the kind of work they do. However, if mobilized, they would be good at public speaking or legally defending socialists. Because some New Agers are susceptible to following Gurus this may work well with Leninist organizations which are sometime cultist (Democratic Workers Party in San Francisco and the Sullivanists in New York, both in the 1980s). New Agers are moderately supportive of feminism. However, many women in New Age cults have been sexually exploited. Socialist feminists would be especially disgusted by this. They would see that women can only gain more power by being part of a movement that includes the working class, which is essentially absent in New Age circles.

Spiritual intentional communities: Burning man, Arcosanti and Findhorn

If a radical socialist labor union were taken on a tour of Findhorn, Soleri’s Arcosanti city, or given admission to a nine-day Burning Man, what would they think? Burning man would be immediately dismissed as a decadent play-pen for spoiled upper-middle class yuppies. Arcosanti would be dismissed as an impractical utopian city which is hopelessly running away from capitalism. Socialist cities have to grow out of a revolutionary struggle, not set up outside of it. Findhorn community would be looked upon as a bunch of spiritual kooks listening to angels.

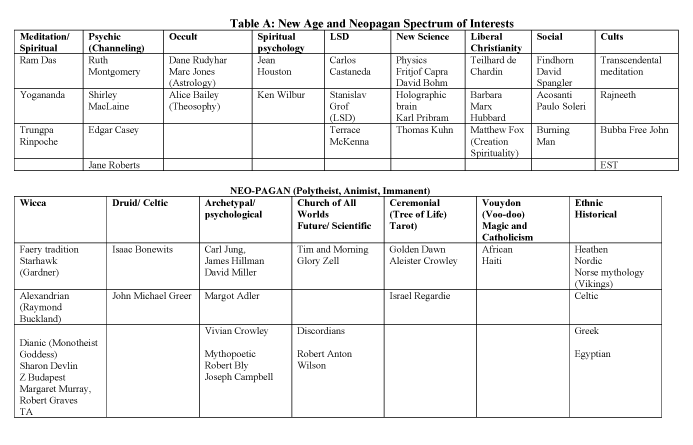

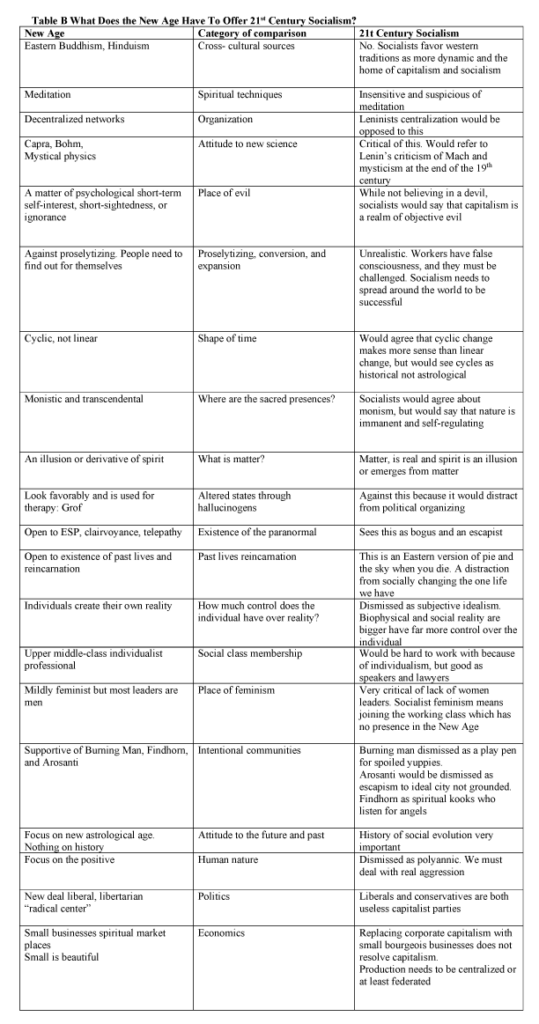

Please have a look at Table A which lays out the New Age spectrum of interests. Following that, please see Table B which summarizes how New Age beliefs and actions compares with 21st century socialism. Across these 20 categories there is not a single clear commonality. Now we will turn to Neopaganism and see what it has to offer socialists.

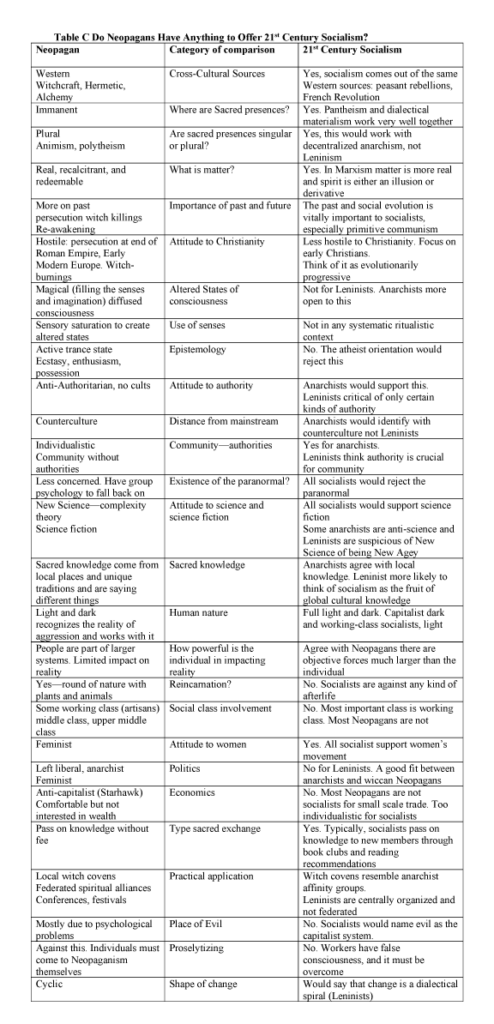

What Does Neopaganism Have to Offer Socialism?

Western magic and matter as creative and self-regulating

Paganism and the western ceremonial magical traditions have deep roots in the West, from ancient Roman times through the Renaissance magicians, alchemists, Rosicrucian’s, and up to the Golden Dawn at the end of the 19th century. All these traditions were committed to in some way redeeming matter, rather than dismissing it or warning that it was an illusion. The “low” magical traditions of witchcraft are more controversial in terms of their origins. But we do know that witches were herbalists and midwifes and were committed to working with and transforming matter. Matter was seen by all magical traditions as creative, self-regulating, and immanent in this world. They are either pantheists or polytheists. Like socialist materialists, matter is seen by pagans a real. There is clearly a relationship between pagan pantheism and dialectical materialism.

Nature and society are objectives forces that impact individuals and only groups change reality

Unlike New Agers, Neopagans would never say individuals “create their own reality”. Neopagan nature is revered and must be taken care of. The forces of nature or the gods and goddesses actively do things to disrupt the plans and schemes of individuals. How would socialists react to this? Very positively. All socialists understand nature and society as evolving. Secondly, socialists understand that the individual by ourselves can change little. It is organized groups which change the world. Since much of Neopagan rituals are group rituals, there would be compatibility in outlook here as well.

Embracing the aggressive and dark side of nature and society

Neopagans could never be accused of being fluffy or Pollyannish. They recognize that there is dark side of nature, and as Jung would say, a shadow side of humanity and individuals. These dark forces must be worked with and integrated. Socialists would agree with this, but in so far as the darkest force on this planet is capitalism, socialists would disagree that there can be any integration with capitalism. Since most Neopagans are not radical socialists, they might see socialists as advocating a dualistic cosmology.

Importance of the past and future and the shape of change

As I said in Part I, the past is very important to Neopagans mostly because of what Christianity did to pagans throughout Western history. Socialists might disagree with the value of Christianity. Some socialists focus on early Christianity and think in some ways Christianity was an evolutionary advance from paganism. Regardless of this difference, the past is also very important to Marxists because primitive communism was an example of how humanity could live without capitalism. Neopagans, like Marxists, are also very pro-science (some anarchists are not) and are very interested in science fiction and how society could be better organized in the future.

However, there is a difference in how the shape of change in conceived. Pagans see change as taking place in cycles with the turning of the seasons over the eight pagan holidays of the years as a model. Marxian socialists would say this misses the fact that cycles turn into dialectical spirals, where the past returns on a higher level. This can be seen in Marxist visions of social evolution when primitive communism returns on a higher level to mature communism after mature communism has appropriated the material wealth produced by capitalism.

Neopagans also seem far less interested in the prospects of paranormal psychology than New Agers are. As I said earlier, good pagan rituals create altered states of consciousness on a regular basis and perhaps, they are not looking for something out of the ordinary if the ordinary rituals can achieve altered states. This is one less obstacle for socialists to overcome.

Attitude towards authority, politics and economics

Unlike the New Age, there has never (to my knowledge) been pagan cults. Neopagans are generally an anti-authoritarian lot and organizing them can be like herding cats.

They are also anti-authoritarian in that most are self-educated like most socialists and do not have many “holy books.” Neopagans, like socialists are very anti-capitalist in that they usually do not charge beginners in terms of passing on knowledge. Dedication to learning, sincerity, and consistency are all that is required. Anarchists and Neopagan witches are sympatico on this. Leninists who are hierarchical in their political organization would have difficulty with Neopagan anti-authoritarianism and they would be dismissed as anarchists.

Politically, many wiccan pagans like Starhawk’s Reclaiming have organized themselves anarchistically with consensus decision making, so they would be on a collision course with Leninists. Even worse, Neopagans who are ceremonial magicians organize themselves in graded orders, with knowledge passed on gradually over many years. This hierarchy in the magical world is then projected into politics. There are real reactionaries and even monarchists involved in ceremonial magic. Another point of difference is over whether or not to proselytize and convert. Like New Agers, Neopagans think people have to come to paganism on their own. Socialists disagree with them, as I discussed in our section on the New Age.

The most predictable anti-capitalists in Neopaganism are wiccans. Wiccans are also very pro-feminist and some are organized where the goddess values of women are predominant. All this is good news for socialists since Margot Adler has said that about half of the roughly 200,000 Neopagans are wiccans. The rest of Neopagans are for small business capitalism like running bookstores or coffee shops rather than supporting big business. Neopagans are more diversified class-wise than New Agers. There are some artisans, white collar working-class, middle-class, and those working with computers. These folks have less resistance to being organized with working class people than the prospect of socialists trying to organize with mostly upper middle-class people as in the New Age.

Altered states of consciousness, sensory saturation, gods and goddesses

I have saved these categories for last because this is the area of Neopaganism that might be the most actively contested by socialists, but it is also the area that I think Neopagans have the most to teach socialists. As I’ve stated in other articles, a good definition of magic is the art and science of changing group consciousness at will by saturating the senses through the use of the arts and images in ritual. Socialists are likely to dismiss this as dangerous because it sweeps people away. They are also likely to confuse this with religious rituals which religious authorities use to control their parishioners for the purposes of mystifying people and asserting control over them. This is a big mistake. Not all rituals are superstitious and when done well, they can empower people and build confidence. People in egalitarian societies, the ones Marxists call primitive communism, understood this.

As far as gods and goddesses go, in a superficial way we can say socialists are atheists and Neopagans believe in gods and goddesses, and that’s the end of it. But it is not so simple. Yes, there are Neopagans who believe in the real existence of gods and goddesses (called “hard polytheists”) but these gods and goddesses do not contain the usual attributes of the monotheistic god. They are not transcendental; they do not promote fear and submission, nor do they have unrealistic, one-sided positive attributes such as all loving and all-knowing. These gods and goddesses don’t infantilize the population. Neither is there a devil as in monotheism. In Greek mythology, for example, all the gods and goddesses have strengths and weaknesses, expressing on a larger scale similar problems as human beings. There are no escape hatches for Neopagans.

Secondly, not all Neopagans believe in the independent existence of gods and goddesses. Some follow the Jungians in claiming the gods and goddesses are archetypes of collective humanity. They are projections along with mythology that shows people how to live. Finally, there are those like myself who are Atheopagans. Led by Mark Green, we see gods and goddesses as metaphors for how to live. In their rituals, Neopagan gods and goddesses are not part of the ritual, but the ritual is very powerful without them.

Conclusion

Of the 23 categories I’ve actively compared between Neopaganism and socialism, there are eight categories where there was full agreement between Neopaganism and social democrats, anarchists, and Leninists. The categories include:

Western sources of influence

The similarities between pantheism and dialectical materialism

Matter is active, self-creative, self-regulating, and independent of mind or spirit

Importance of the past—paganism before Christianity; primitive communism before class societies

Importance of the future in the form of science fiction

Recognition and acceptance of the aggressive and dark side of nature and humanity

Very pro-feminist—emphasis on goddesses in Neopaganism and socialist feminism

Passing on special knowledge without economic exchange. Importance of self-education

In addition, the political decentralization of the anarchists is directly in line with wiccan covens. This is a direct challenge to any kind of federation or centralization, whether it be Leninists or Social democrats. Given that, according to Margot Adler, about half of Neopagans are wiccans, there is an even stronger connection between anarchism and Neopaganism.

In other articles I’ve named some of the major components of 21st century socialism for Yankeedom. A mass political party which analyzes, generalizes, and spreads working-class self-organization: the presence of newsletters like Labor Notes which tracks working class struggles around Yankeedom; the presence of a transition program which shows workers our plans 3,5, 10 years down the road; the presence of worker cooperatives where workers rehearse how to make decisions about what to produce, how to produce it, and where the product should go as well as how much to pay themselves. Lastly, economic theorists which track the crisis in capitalism and project various alternative socialist economic models. In socialist economics, this would the work of Richard Wolff, David Harvey, Anwar Shaikh, Michael Roberts, and John Bellamy Foster. Since most of these economists are social democrats, they might have some appeal to Neopagan New Deal liberals who might be curious about socialism. The work of anarchist economist David Graeber would be perfect for Neopagan witch anarchists. With the possible exception of a transition program, Neopagans could easily be brought in.

However, where Neopagans have most to offer socialists is their ability to do meaningful rituals during the course of the seasons of the year. There are eight Neopagan holidays throughout the year: Yule (Winter Solstice); Brigid (Candlemas); Eostar (Spring Equinox); Beltane (May Day); Litha (Summer Solstice); Lughnasad; Mabon (Fall Equinox); Samahin (Halloween). People all over the world celebrate some or even all these holidays. The benefit of celebrating these holidays is that it gives a cyclic dimension to social life. It harnesses us to nature and the turning of the seasons.

The history of socialism is out-to-lunch in not understanding the importance of cycles of the seasons to human beings. It is one of many reasons why nationalism, sports, and religion have been more attractive to the working-class than socialism. Sports is rooted in the seasons of the year. For baseball, spring to fall, then next spring and next fall. For football, its fall and winter. Nationalism has its special holidays peppered throughout the year that are connected to the seasons. So does religion. What do socialists have to celebrate seasons? Nothing. Socialists have no yearly rhythm. Strikes, boycotts, and protests all rise in reaction to a particular event. When they are over, there is no grounding in how they might be connected to the spring and summer. There is no socialist respect for the turning of the seasons in nature and that we are partly biological beings who need rituals to ground us in the seasons. As I’ve said in other articles, we need socialists in the arts, especially in dance, music, choreography, and playwriting to join with Neopagans who are already good at this. Socialism badly needs seasonal rituals if it is to compete with sports, nationalism, and religion.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Bruce

Bruce Lerro has taught for 25 years as an adjunct college professor of psychology at Golden Gate University, Dominican University and Diablo Valley College. He has applied a Vygotskian socio-historical perspective to his four books: From Earth-Spirits to Sky-Gods: the Socio-ecological Origins of Monotheism, Individualism and Hyper-Abstract Reasoning Power in Eden: The Emergence of Gender Hierarchies in the Ancient World Co-Authored with Christopher Chase-Dunn Social Change: Globalization from the Stone Age to the Present and Lucifer's Labyrinth: Individualism, Hyper-Abstract Thinking and the Process of Becoming Civilized He is also a representational artist specializing in pen-and-ink drawings. Bruce is a libertarian communist and lives in Olympia WA.