Exclusive to Ekurd.net

Impressions made from Sumerian cylinder seal (and section of the seal itself far left) with: 4.2 x 2.5cm (seal). Photo: Courtesy of the Yale Babylonian Collection. Photography by Klaus Wagensonner (seal) and Graham S. Haber (impression). [1]Sheri Laizer |

Ziggurats – The Meeting Place of Humanity with the Cosmos

To get behind the three major monotheistic religions and tap the mindset of the earliest civilizations of ancient Mesopotamia I felt that I had to be there –both mentally, and if possible, physically. In 1982, a year into my intense research into ancient Sumerian culture, Iraq was entering her second year of war against fundamentalist Iran. Hours spent using my reader’s card for the British Library, that was still then part of the British Museum gave me access to Sumerian art, literature, and the Sumerian cosmos but I wanted to go to Iraq.

The personnel of the Iraqi Embassy, and the Iraqi Cultural Centre were also most hospitable and encouraging of my ‘Ziggurats’ [2] book endeavour to revive what it was like to live there around 2300 BC. At the time, Saddam Hussein’s government was producing high quality publications in English like Ur Magazine.

When I began my research, let us remember that there was as yet no Internet, no Smart Phones, no instant online searches. Work was done through reading whatever published texts were available and examining artefacts. I typed my book, Ziggurats on a golf ball typewriter. Corrections were made with Tipex or white corrector ribbon on a spool. Communications for official purposes, like following up on the progress of visa applications went off by telex.

My requests made in this way to Baghdad in 1982 did not produce a reply despite the assistance of the Iraqi Cultural Centre or therefore the longed-for visa because of the war with Iran. I decided in view of that to carry out my physical placement in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt. It was an excellent choice. On the west bank of the Nile, I stayed in a very simple hotel for two Egyptian pounds a day. I read the books I had lugged there with me surrounded by palm trees and village culture and slowly wrote the book. It seemed obscure to people at the time and I set it aside, getting caught up in modern politics in the Middle East after moving north from Egypt to Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories to escape the increasing heat of southern Egypt. From there, I went on to Turkey and travelled in Turkish Kurdistan with Kurds I met there and later, in London. This led to my books on Kurdistan and a number of books and articles translated with Kurdish writers. Still, ‘Ziggurats’ laid on one side untouched in its original typed ms.

I had made three photocopies of the typed ms. of Ziggurats, held together by comb binding. One copy had gone to the Iraqi Cultural Attaché, another went to Peter Gabriel with whom I shared all my work, and the final was kept safe with the original ms. at home in Battersea, south London. Of all the things I have lost in the intervening decades, fortunately I did not lose that manuscript.

Ultimately, I obtained a tourist visa to Iraq a year after the ceasefire was signed between Iraq and Iran in October 1989 on a government sponsored tour aimed at showcasing reconstruction. An international group of journalists, we were taken to the ancient site of Babylon, the devastated south of Basra and Faw, to Kirkuk, Mosul, Erbil, Amadiya and Sulaymaniya as well as the historic sites of Baghdad like the inspiring split-onion dome Martyrs monument. My visa had been granted because of my Sumerian work – my Kurdish association naturally remained in the shadows.

In October 1989, therefore I at last inhaled the scents of Mesopotamia and felt that I had come home. I knew it so well from the work I had been doing. I had come to understand the Sumerian gods to represent the natural forces and astral bodies evoked by the Sumerian cosmologists, kings, artists and poets in an age when female deities were equal to men. Enheduanna, the high priestess of Ur was the first female author recorded back in the 23rd century BCE. [3]

In this way, the setting for my narrative, Ziggurats, paid homage to the ancient human mind – an enlightened culture that brought written language, law, art and science into human time. It was also that research that led me to political Kurdistan.

Human time and the study of the cosmos

In ancient Mesopotamia, along with the Sun, the Moon, the stars, and heavenly constellations, the five visible planets were recognised and studied by the priests and dignitaries of the temples and palaces. The texts intertwined astronomical, astrological, and religious aspects concerning the Moon and the planets into an overall organic astral body of knowledge. Astrology and celestial divination developed into firm lore. The Moon, the Sun, and the planets were interpreted as manifestations of divinities.

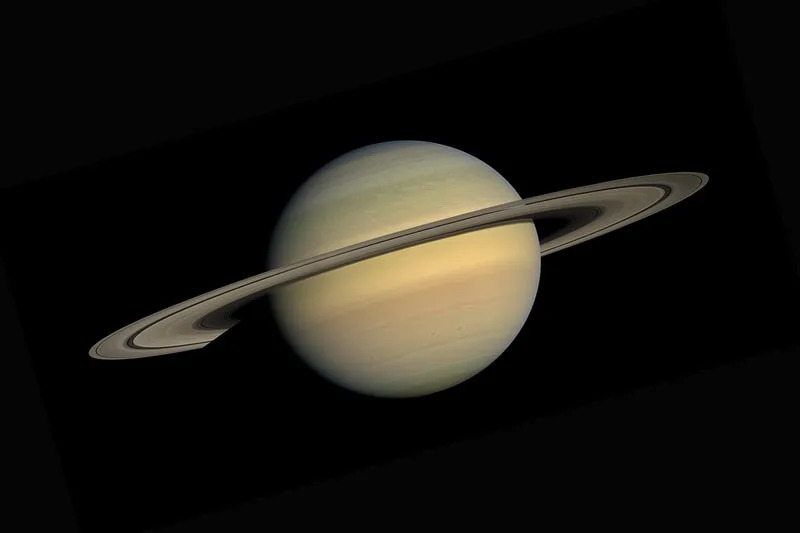

The Mesopotamians also developed a calendar from around 3000 BCE divided into years and months, evidence that they studied the Moon from the earliest times. The Sumerian and Akkadian names for the Moon god, Nanna/Sin, appear in cuneiform since approximately 2500 BCE. Akkadian names for the five planets, Mercury (Šiḫṭu), Venus (Dilbat), Mars (Ṣalbatānu), Jupiter (the White Star), and Saturn (Kayyāmānu), first appear in tablet texts from around 1800–1000 BCE when the phenomena of the Moon, the Sun, and the planets were interpreted as signs by the gods to communicate with human beings. Later Babylonian scholars between ca. 600-100 BCE reported lunar and planetary phenomena in astronomical records and ephemeris form in order facilitate predictions with time-based methods still in use by astrologers today. After the end of the 5th century BCE, Babylonian astronomers introduced the zodiac and developed new methods for predicting lunar and planetary phenomena known as mathematical astronomy. They developed horoscopy and other forms of astrology that use the zodiac, the Moon, the Sun, and the planets to predict events on Earth. [4]

They also discovered the 360-degree circle and devised the sixty-minute hour, additionally using a water measure of periods of double-hours…

Sumerian records of Erbil

The city of Erbil (Urbi-Lum) grew up on the flat Erbil plain and is mentioned in Sumerian sacred writings under the name of Urbi-Lum (Urbilum) or Arbilum, and Orbelum, followed by successive variants. The modern name أربيل Erbil is derived from Arba-Illu, with alterative renderings as Arbailu, Arabales, Arbira, Urbel, Arbail, Arbira, Arbela, Erbil/Arbil. The name Urbi-Lum was adduced by the Sumerian King Shulgi of the third dynasty (2000 BCE).

UNESCO has noted: “Written and iconographic historical records document the antiquity of settlement on the site…since pre-Sumerian times in several written sources. Archaeological finds and investigations suggest that the mound conceals the levels and remains of several layers of previous settlements, while the immediate and wider setting has revealed traces connected to the early development…It preserves over thirty metres of archaeological deposits going back to the very early beginnings of urbanisation in Mesopotamia. [6]

Erbil: Veneration of the goddess of love and war, Innana/ Ishtar

The Temple of Ishtar (Sumerian Inanna) that completed the top level of the sacred man-made hill that became the citadel in Erbil was typical of the sacred Sumerian sites within city centres. From around 3000 BCE, Urbi-Lum had come under Sumerian rule enduring until the rise of the Akkadian Empire (2335–2154 BC), in which the Sumerians and Akkadians, who spoke a Semitic language became one nation. [7]

Named as the Stele of Ishtar parading upon a lion from the Neo-Assyrian period 8th century BCE. (Louvre) from Tell Amar in the Erbil plain. Photo: Louvre.fr [8]Erbil was captured in 2150 BCE, by the Gutian King of Sumer, Erridu-Pizir. [9] King Shulgi subsequently sacked it during his 43rd year on the throne [10], and his Neo-Sumerian successor, Amar-Sin, sacked it anew and incorporated it into the greater Ur III state. [11]

By the 18th century BCE, Erbil features in a list of cities taken over in conquest by Shamshi-Adad of Upper Mesopotamia and Dadusha of Eshnunna [12] during their campaign against the land of Qabra. Now, Qabra is believed to be the site just south of today’s Erbil city called Kurd-Qaburstan, dating back to the Bronze Age a 118-hectare site with an 11-hectare central mound 17 metres high surrounded by an 84-hectare walled town lower down. The site is located at an important point midway between the Upper and Lower Zab rivers, and sits near a pass traversing the hills between Makhmur and Erbil, near to where, of current interest, the terror group, ISIS, has been regrouping since being expelled from Mosul late in 2017. The defeat and capture of Qabra by the two kings mentioned above are recorded on two stone steles, one retained by the Iraq Museum in Baghdad and the other still held in the Louvre. [13]

View from the lower town of Kurd-Qaburstan situated to the west of the mound. Photo: krieger.jhu.edu [14]

A most intriguing letter on the dying Sumerian language and its use in ancient Erbil at the Qabra (Kurd-Qaburstan) site written to the King of Mari, Yasmah-Addu (1795-1776 BCE) has come down to us today:

“You wrote me to send you a man who deciphers the Sumerian in these terms: “Take for me a man who deciphers the Sumerian and speaks Amorite”. Who deciphers Sumerian and lives close to me? Well, should I send to you Šu-Ea who deciphers the Sumerian? […] Iškur-zi-kalama deciphers the Sumerian, but he holds a position in the administration. Should he leave and come to your house? Nanna-palil deciphers the Sumerian, but I must send him to Qabra). You wrote me this: “May someone send me a man from Rapiqum who can decipher the Sumerian!” There is no one here who reads Sumerian!” [16]

For centuries thereafter Sumerian was lost. Now, huge strides in deciphering the cuneiform texts in which Sumerian was written have been made and their content revealed to modernity.

The Assyrians used the name arba’ū ilū (Arba-Illu), meaning ‘four gods’ according to Assyrian etymology and the oral tradition. Ishtar (Sumerian Inanna) remained one of the most important in the region under the Assyrians along with Assur, their patron god, whilst the identities of the remaining two gods are not now known. Under Assyrian King, Shalmaneser I (in power between 1273 – 1244 BCE) Erbil was an important provincial capital and a safe and secure part of the Middle Assyrian Empire.

King Shalmaneser I, boasted, “I built the Egašankalamma, the temple of Ishtar, the Lady of Arbil, my Lady, together with its ziggurat.“ [17]

The Kurdish name for Erbil is Hewlêr, which is believed to derive from the ancient Greek meaning “Temple of the Sun” from the Greek helio and may be associated with the Kurdish sun-worshipping religions, Mithraism, Zoroastrianism and of the Yazidi beliefs.

From the many sherds of pottery discovered on Erbil’s mound, or ancient tell, archaeologists believe Erbil was probably occupied since Neolithic times and certainly during the Copper Age (Chalcolithic or Eneolithic period), because fragments found there resemble the earthenware uncovered in the Jazira and in Anatolia from both the Ubaid and Uruk periods.

Erbil’s citadel site is believed to be the oldest continuously inhabited town in the world.

What is visible of Erbil city’s mound and citadel today is of much later date. The ziggurat and temple of Ishtar lie as dust beneath the Ottoman Turkish fortified settlement constructed in a sequence of alleys and cul-de-sacs that fan outwards from the Great Gate. A line forming a wall of tall 19th century house-fronts and habitations made of clay brickwork evoke the former grandeur of the fortress that dominated the city below. The elegant residential structures dating from the 18th – 20th centuries are being reconstructed and preserved by UNESCO with the co-operation of the Kurdish authorities. [18]

Dur Kurigalzu – the site northwest of Baghdad known today as Aqar Quf

(dedicated toEnlil- the Sumerian god of Enlightenment, storm and wind who decreed the fates)

The author, Sheri Laizer, gets to visit the ziggurat at Dur Kurigalzu in 2021 after many visits to the Erbil citadel. Photo: Sheri Laizer/via Ekurd.net

Dur Kurigalzu is a Kassite site and a significant part of its ziggurat remains visible. Dur is Akkadian, and means ‘fortress’, so it is the fortress of King Kurigalzu (now known as Aqar Quf). The ziggurat temple and surrounding city ruins lie some 30 kms northwest of Baghdad on the site of ancient Parsa dating back to the 14th-15th century BCE and the Kassite Kingdom of Kurigalzu I (1400 -1375 BCE) who from his seat there ruled over all Mesopotamia.

It is believed that the Kassites arrived in Mesopotamia from the Zagros mountains. They then rebuilt the cities of Nippur, Larsa, Susa and Sippar. The ziggurat at Aqar Quf was restored to its first level by President Saddam Hussein. Since regime change was imposed by the US-led invasion in the spring of 2003, Dur Kurigalzu has been neglected like the ancient Persian arch of Ctesiphon and the sprawling ruins Babylon that I also visited. Once highly frequented by locals and tourists, the sites are now the domain of stray dogs and bored military guards.

King Kurigalzu I’s impressive capital was later taken over by the Assyrian Kings. In the 1940s, Seton Lloyd and Taha Baqir led an Iraqi-British team at the site and discovered some hundred clay tablets as well as the fragments of a statue decorated with texts in Sumerian representing King Kurigalzu I. The dig also exposed the ruins of the 3,500-year-old ziggurat.

Dedicated to the Sumerian god, Enlil, the god of enlightenment, the ziggurat is among the best preserved of the Mesopotamian temple ziggurats, lying far to the north of the Sumerian city sites built between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers at the head of the sweet water marshes of Dhi Qar.

Enlil was the head of the Sumerian pantheon, a forerunner of the monotheistic God. His command was supreme and unalterable, and the destinies of men lay in his hands. He was the god of air, wind and earth, of the breath of life. From the Sumerian also came the story of the Flood and the creation myth of Man created from earth. Enlil divided the earth with a hoe, breaking the hard surface of the ground for seeds to grow. Men also came forth from the opening of the earth.

Worship of Enlil and of Inanna/Ishtar continued down through the Akkadians, Babylonians, Assyrians and Hurrians and he would also have been on the gods of Erbil, likely one of the two no longer known in addition to Ishtar and Assur. The Assyrians had also continued to worship the main four Sumerian gods, Enlil, An (Anu) Enki the god of water and wisdom and added their patron deity, Assur. Merchant traders would swear by the names of Ishtar, Ashur, and Nisaba that they were speaking the truth. [19]

Part of a Sumerian clay tablet depicting the god Enlil with his ring of power. Stele of king Ur-Namma, fragment showing the god Nanna seated on a throne, in front of the king (mainly lost). Found in 1927 in Ur. Penn Museum.

The lowest terrace of Enlil’s temple ziggurat was restored, and the structure’s mud-brick core rises above the surrounding plain with its palm trees and dusty scrub to a height of around 170 feet. It is flanked to the south by the ruins of three temples, several sanctuaries and the King’s former palace whose corridor walls had been decorated with numerous male figures, most likely thought to be dignitaries of the palace based on surviving works of sculpture. [20]

(Coming shortly: Part Two – The Ahwar and southern Mesopotamian temple ziggurats city sites with the most important at Ur, as below, courtesy of UNESCO) partly restored by Saddam Hussein.)

1 IMAGES: Courtesy of the Yale Babylonian Collection. Photography by Klaus Wagensonner (seal) and Graham S. Haber (impression).

2 Unir is the most common Sumerian word for ‘ziggurat’, and literally means “high-up (nir) amazingness (u(g))”. A literary term also exists for ‘ziggurat’, hursanggalam, which means “skillfully crafted (galam) mountain (hursang)”. Urbi-Lum (Erbil) had its own ziggurat and temple and is recorded in the Sumerian texts.

3 https://the-past.com/feature/prayer-and-poetry-enheduanna-and-the-women-of-mesopotamia/

4 https://oxfordre.com/planetaryscience/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190647926.001.0001/acrefore-9780190647926-e-198#acrefore-9780190647926-e-198-div1-1

5 See archaeological study at

7 The term ‘Semitic’ denotes a group of languages that include Arabic, Hebrew, Aramaic and the ancient languages of the Akkadians and Phoenicians termed as Afro-Asiatic languages. In contrast, Sumerian (Emegir meaning ‘native tongue’ and the literary form, Emesir) is a non-Semitic, lone or isolated language spoken since around 3000 BCE. Gordon Whittaker [30] postulates that the language of the proto-literary texts from the Late Uruk period (c. 3350–3100 BC) is really an early Indo-European language which he terms “Euphratic” (from the Euphrates river region) or Proto-Euphratean or Indo-European. See Gordon Whittaker at https://www.academia.edu/3592967/Euphratic_A_phonological_sketch from which the words, *ĝȹdȹōm dluk-ú- ‘the sweet earth’ → Ga2-tum3-dug3(u)44 ‘(mother goddess of Lagash)’… h2ner- ‘charismatic power’ → ner ~ nir ‘trust; authority; confidence’, parik-eh2- ‘courtesan, wanton woman’ > Eu. *karikah2- → kar(a)- ke3 / 4 ~ kar-a-ke4 ‘sexually free woman; (epithet of the goddess Inanna)’19 (metathesized from *karika) etc.

8 https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010136226

9 Douglas Frayne, “Gutium” in “Sargonic and Gutian Periods (2234-2113 BC)”, RIM The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia Volume 2, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 219-230, 1993 ISBN 0-8020-0593-4

10 Potts, D. T. (1999). The Archaeology of Elam. Cambridge University Press. p. 132. ISBN 9780521564960.

11 See a collection of papers on pre-Islamic Erbil at https://www.researchgate.net/

12 Eshnunna was also occupied through the Akkadian period and Ur III. Areas of the Northern Palace date to this period and show some of the earliest examples of widespread sewage disposal engineering including toilets in private homes. George, A. R. “On Babylonian Lavatories and Sewers.”, Iraq, vol. 77, 2015, pp. 75–106

13 Aruz et al. 2008; Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C. New York: 2008, Metropolitan Museum of Art cited in https://sites.krieger.jhu.edu/kurd-qaburstan/about-the-site/ and Ismail and Cavigneaux 2003

17 Ishtar’s temple and ziggurat had pre-existed such that the King had rebuilt it or undertook a new construction there.

19 K.R.Veenhof and Dr.Edhem Eldem, 2008, p. 103

https://www.ancientpages.com/2019/05/03/ancient-ziggurat-of-aqar-quf-dedicated-to-god-enlil/

Sheri Laizer, a Middle East and North African expert specialist and well known commentator on the Kurdish issue. She is a senior contributing writer for Ekurd.net. More about Sheri Laizer see below.

The opinions are those of the writer and do not necessarily represent the views of Ekurd.net or its editors.

Copyright © 2024 Ekurd.net. All rights reserved