Feminism, Intersectionality, and Marxism

Josefina L. Martínez

Debates on gender, race, and class: How can the working class become hegemonic in struggles against oppression?

Intersectionality is a word that is frequently used in academia, among feminist activists, and in social movements. “Class, race and gender” are, as Terry Eagleton pointed out, the “contemporary holy trinity.”1 There is a lot of discourse about intersectionality, but the definition of the term is often unclear. Is it a theory or an empirical description? Does it operate in the realm of individual subjectivity or does it analyze systems of domination? And finally, what does it say about the causes of intersecting oppressions and, above all, about the paths toward emancipation?

Although reflections on the relationship between gender, race, and class had long existed in Marxist debates and among the left, the concept of intersectionality was defined for the first time as such in a 1989 article by Black lawyer and feminist Kimberlé Crenshaw2 that aimed to answer these questions in the context of U.S. anti-discrimination law. That origin undoubtedly marked the concept, as we will see later. However, its most important precedent is in the work of Black feminists of the 1970s, such as those of the Combahee River Collective, who offered an “intersectional” critique of liberation movements in the context of Second Wave feminism and the political radicalization of the time.

In this article, I briefly summarize the historical background of the concept, its first formulations, how it shifted with the rise of postmodernism, and the ongoing debate on the concept within today’s social movements. I also critically contrast the theories of intersectionality with Marxism.

1. The Combahee River Collective and Black Feminists

The Combahee River Collective Statement, published in 1977, took its name as a tribute to the brave military actions led by former slave and abolitionist Harriet Tubman in 1863, which led 750 enslaved people to liberation through enemy fire. She was the only woman to run an army operation during the U.S. Civil War.

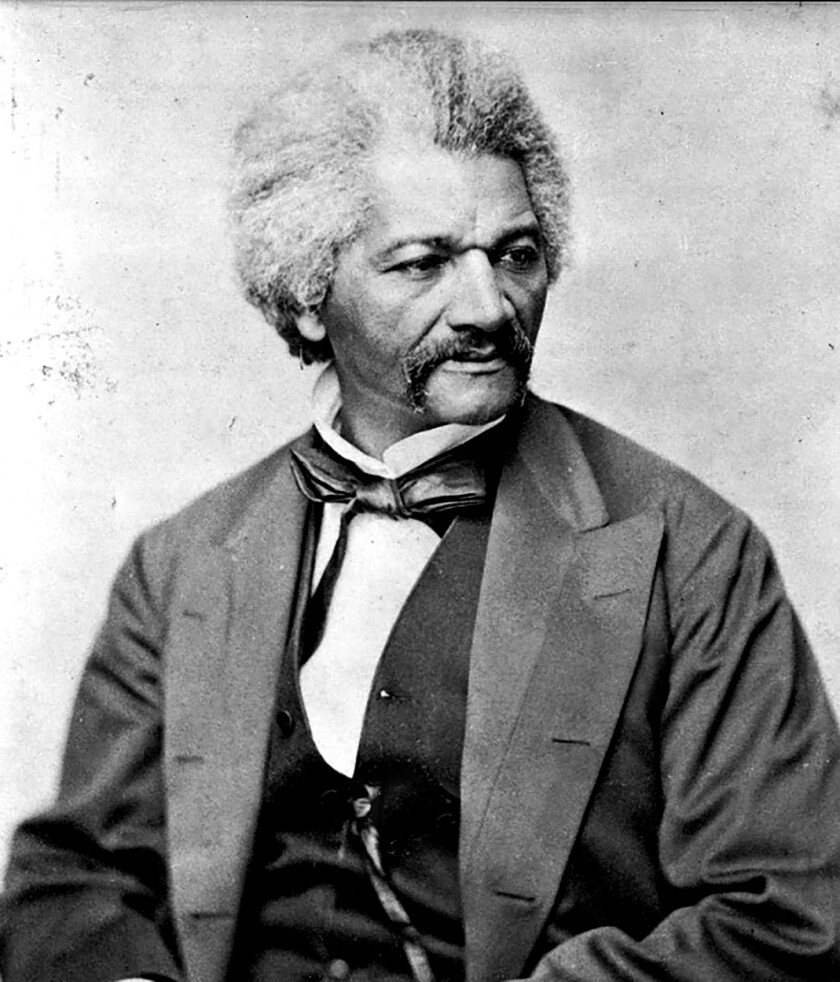

Black feminists in the 1970s saw themselves as part of a historical tradition of Black women’s struggles dating back to the 19th century. In her book Women, Race and Class,3, Angela Davis referred to their role in the U.S. abolitionist movement. Sojourner Truth’s speech at the Ohio Women’s Convention for women’s suffrage in 1851 went down in history. One man had argued that women couldn’t vote because they were the “weaker sex,” to which Sojourner Truth gave a powerful response:

I have ploughed, and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man — when I could get it — and bear the lash as well! And ain’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery … And ain’t I a woman?

Her response was a rebuttal of the patriarchal narrative that constructed “femininity” based on the idea that women are weak, “naturally” inferior beings incapable of exercising political citizenship. But it also challenged the many white suffragettes who neglected the demands of Black and working women.

In the mid-1970s, a number of Black women, having had negative experiences in the white feminist movement and in organizations for Black liberation, decided to revive that tradition and form their own militant groups. With the publication of the Combahee River Collective Statement, Black feminists simultaneously questioned white feminism, the Black movement, and the bourgeois Black feminism of the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO).

Their starting point was the shared experience of simultaneous oppressions rooted in the trilogy of class, race, and gender, to which they added sexual oppression. From there, they aimed their critique against the feminist movement that was hegemonized by radical feminism. This current of feminism interpreted social contradictions through the opposition between “sexual classes”4 and prioritized one system of domination — the patriarchy — over all others5. While questioning the preeminence of sexual or gender oppression over that of race and class, Black feminists also debated against the openly separatist tendencies that promoted a “war of the sexes,” which had gained strength in the feminist movement of the late 1970s. The Black feminists defined this type of feminism as a movement guided by the interests of white, middle-class women. They also maintained that any kind of biological determination of identity could lead to reactionary positions.

Although we are feminists and Lesbians, we feel solidarity with progressive Black men and do not advocate the fractionalization that white women who are separatists demand.

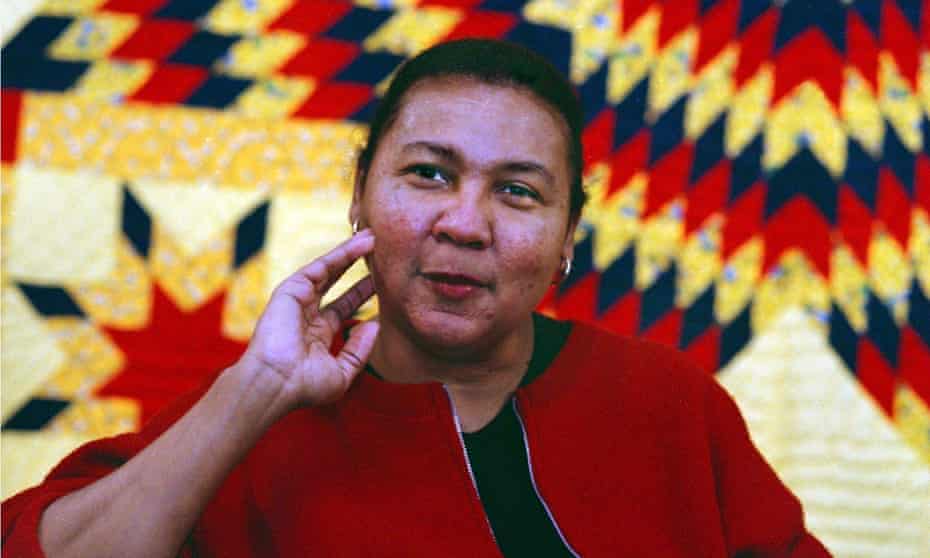

In her book Feminism Is for Everybody, Black feminist bell hooks argues that, in those years, “utopian visions of sisterhood” and the ahistorical definition of patriarchy were challenged by debates around race and class. Taking stock of this period, she asserts that “white women who had attempted to organize the movement around the banner of common oppression evoking the notion that women constituted a sexual class/caste were the most reluctant to acknowledge differences among women.” She also highlights the debate with the separatist currents within the movement:

They portrayed all men as the enemy in order to represent all women as victims. This focus on men deflected attention from the class privilege of individual feminist activists as well as their desire to increase their class power.6

The Combahee River Collective Statement characterized the struggle for the emancipation of Black women and Black people as inseparable from the struggle against the capitalist system. That is why its authors explicitly supported the fight for socialism:

We realize that the liberation of all oppressed peoples necessitates the destruction of the political-economic systems of capitalism and imperialism as well as patriarchy. We are socialists because we believe that work must be organized for the collective benefit of those who do the work and create the products … We are not convinced, however, that a socialist revolution that is not also a feminist and anti-racist revolution will guarantee our liberation.

In relation to Marxism, they asserted a fundamental agreement with Marx’s theory regarding “specific economic relations,” but they believed that the analysis had to be “extended further in order for us to understand our specific economic situation as Black women.” It should be noted that although they expressed the need for a socialist revolution, the practical tasks they proposed as a group were limited above all to self-awareness workshops and the struggle for the specific rights of Black women in their neighborhoods.

The notion of identity politics appears in the Statement as a response to the specific way in which Black women experience oppression. Recognition of one’s own identity is considered necessary for converging, a posteriori, with other liberation movements. There is tension between the constitution of a differentiated identity and convergence with other oppressed people to fight against a system that combines forms of economic, sexual, and racial domination.

A few years later, however, as the social, political, and ideological context drastically changed with the rise of neoliberalism and postmodernism, the concept of intersectionality would take on new meaning. With the radical transformation of society no longer on the horizon, the moment for collective action tended to dissipate, and differentiated “identities” and the demand for policies of recognition within capitalist society began to increase.

2. Intersectionality as a Category of Discrimination

Kimberlé Crenshaw first defined the concept of intersectionality in 1989. She highlighted that the separate treatment of race and gender discriminations as “mutually exclusive categories of experience and analysis” had problematic consequences for legal doctrine, feminist theory, and anti-racist politics. She thus proposed that a contrast should be drawn between “the multidimensionality of Black women’s experience [and] the single-axis analysis that distorts these experiences.”

She pointed out that any conceptualization based on a single axis of discrimination (whether it be race, gender, sexuality, or class) erases Black women from identification and the possibility of ending discrimination, limiting the analysis to the experiences of privileged members of each group. Racial discrimination tends to be viewed from the perspective of Black people with gender or class privileges, while with gender discrimination the focus is on white women with economic resources. Since “the intersectional experience is greater than the sum of racism and sexism, any analysis that does not take intersectionality into account cannot sufficiently address the particular manner in which Black women are subordinated.”

In her analysis, Crenshaw examines how several lawsuits brought by Black women were simply dismissed by the judiciary. In one case, DeGraffenreid v. General Motors, five women sued the multinational, alleging employment discrimination because as Black women they were denied promotions to better positions. The court dismissed the lawsuit, claiming that it was not possible to establish the existence of discrimination because they were “Black women,” as they did not constitute a group subject to special discrimination. Instead, the court agreed to an investigation of whether racial or gender segregation had occurred, but “not a combination of both.” Finally, it determined that since GM had hired women – white women – there was no gender discrimination involved. And since the company had also hired Black people – Black men – there was no racial discrimination involved either.

The Black women’s lawsuit was unsuccessful. The court claimed that its admission would open up a “Pandora’s box.”

Crenshaw points out that the objective of intersectionality is to recognize that Black women may experience discrimination that has complex forms, which the single-axis conceptual framework fails to address. In the late 1980s, the concept of intersectionality emerged as a category for addressing the complexity of experiences of “discrimination,” with the aim of establishing new case law that would allow “diversity policies” to be regulated by the state.

Later, U.S. sociologist and scholar of Black feminism Patricia Hill Collins defined intersectionality as “being constructed within an historically specific matrix of domination characterized by intersecting oppressions.”7 In her view, intersectionality defines a “social justice” project that seeks a convergence or coalitions with other “social justice projects.”

The concept of intersectionality was subsequently developed by many other Black, Latina, and Asian feminist intellectuals within the expanding framework of “Women Studies” in academia. Intersectionality became a buzzword at conferences and symposia, and in research departments. NGOs were created to develop intersectional studies in the fields of economics, law, sociology, culture, and public policy. Other vectors of oppression were added to the trilogy of gender, race, and class, such as sexuality, nationality, age, and functional diversity. But while this increased the visibility of the specific oppression faced by multiple groups and communities, it paradoxically developed in a climate of resignation to capitalist social structures, which had come to be perceived as impossible to challenge.

3. Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Multiple Differences

The rise of intersectionality studies in academia coincided with the beginning of a new historical phase that completely transformed the intellectual and political climate under neoliberalism. The period of “Bourgeois Restoration”8 or neoliberal boom saw generalized attacks on workers’ gains worldwide, with privatization and deregulation policies running rampant given the defection of the trade union and political leaderships of the working class. This led to an increase in the internal fragmentation of the working class and a huge loss of class subjectivity.

In this new context, the radicalism of the Black feminists and socialists of the Combahee River Collective gave way to a formulation of intersectionality in the framework of an increased fragmentation of subjects, from a postmodern perspective. The idea of intersectionality became more akin to that of “diversity” and “identity politics.” Such a formulation shifts the focus from the collective to the individual, from the material to the subjective, in a process of “culturalization” of the relations of domination. It generalizes the idea that the struggle of oppressed groups fundamentally involves acquiring self-awareness of their own identity — a “situated knowledge” — to ensure that privileged groups (men, white women, heterosexual women, etc.) “deconstruct” their privileges and recognize diversity. In the framework of the postmodern “cultural shift,” identities are presented as exclusively constructed in discourse, so the possibilities of resisting are restricted to the establishment of a counter-narrative.

This perspective, however, cannot be applied to class exploitation: Can we expect those who own the means of production — bankers and capitalists — to “deconstruct” their power through self-reflection? In reality, the proposition is also useless as a strategy for ending racism, heterosexism, and sexism, unless these “axes of domination” are considered to be separate entities that operate exclusively in the cultural or ideological sphere, rather than being intertwined with the material and structural relations of capitalism.

Conversely, the multiplication of an increasingly extensive series of oppressed identities, without considering the possibility of radically transforming the capitalist social relations on which these oppressions are based, gave rise to practices of “ghettoization” and separation in activism. Pratibha Parmar warned of this problem in her work:

There has been an emphasis on accumulating a collection of oppressed identities which in turn have given rise to hierarchy of oppression. Such scaling has not only been destructive, but divisive and immobilising. … [M]any women have retreated into ghettoised “lifestyle politics” and find themselves unable to move beyond personal and individual experience.9

As the counterpart to this impotence, the capitalist system appropriated the explosion of “diversity” as a market of identities, which it could assimilate as long as they did not challenge the social system as a whole. Terry Eagleton noted with regard to postmodernism:

One would be forced to claim that [given] its single most enduring achievement, the fact that it has helped to place questions of sexuality, gender and ethnicity so firmly on the political agenda, that it is impossible to imagine them being erased without an almighty struggle was nothing more than a substitute for more classical forms of radical politics which dealt in class, state, ideology, revolution, material modes of production.10

In a footnote, however, Eagleton clarified that it had not been postmodern intellectuals who had placed those issues on the political agenda, but the previous action of social movements through struggles in the 1960s and 1970s. Once that wave of political radicalization was defeated, the visibility of issues of race, gender and sexuality grew, while class became increasingly invisible (to the point that some authors have written about the disappearance of the working class as such).

4. The Retreat from Class Politics

In the class/race/gender trilogy, class tended to be diluted, or became just another identity, as if it were a category of social stratification (by income) or type of occupation. Citing Collins, Marta E. Giménez11 notes that one of the characteristic elements of intersectionality theories is the assumption that “in order to theorise these connections it is necessary ‘to support a working hypothesis of equivalency between oppressions’,” but that this leads to the elimination of the specificity of class relations.

Against this view, it is necessary to point out that race, gender, and class are not directly comparable categories. This does not mean that we must establish a hierarchy of grievances, or determine which is most important to people’s subjective experience; the goal is to achieve a greater understanding of the relationship between oppression and exploitation in capitalist society.

For example, class, race, and gender operate very differently in relation to “equality” and “difference.” Historically, the bourgeoisie has tried to camouflage class “social differences” as much as possible behind an “egalitarian” ideology of “free contract.” But it uses racism and sexism to establish “differences” that are attributed to biological or “natural” conditions to justify inequality in the distribution of resources and access to rights and to defend the persistence of a certain division of labor or, simply put, the enslavement of millions of people, dehumanizing them.

From an emancipatory perspective, the objective is to ensure that no difference in skin color, birthplace, biological sex, or sexual choice can be used as a basis for oppression, grievances, or inequality, while recognizing diversity and promoting the development of the creative potential of all individuals within the framework of social cooperation. But in the case of class differences, the aim is to eliminate them completely, as such. Through its struggle against capitalist social relations, the working class seeks to eliminate the private ownership of the means of production, which entails the elimination of the bourgeoisie as a class and the possibility of ending all class society.

What structures capitalist society is the social difference between the owners of the means of production and those who are forced to sell their labor power in exchange for wages, beyond all attempts to render this contradiction invisible. Patriarchal relations — which emerged thousands of years before capitalism — and racism are not ahistorical entities, but have taken on new forms and a specific social content in the framework of capitalist social relations.

Capitalism uses patriarchal prejudices to establish an unprecedented differentiation between the “public” and the “private,” between the sphere of production and the sphere of the home, where women sustain — through invisible work — a large part of the tasks of social reproduction of the labor power needed for the reproduction of capital. Institutions such as the family, marriage, and heterosexual normativity, reformulated under new social relations, socialize and naturalize this role for women. The multiple manifestations of gender oppression and the painful grievances that they imply for millions of women through violence and femicide are not “reducible” to class relations, but they cannot be explained without connecting the categories of oppression and exploitation.

Racism was used to provide an ideological justification for enslaving millions of human beings, while at the same time the Enlightenment elevated the ideas of “freedom,” “equality,” and “fraternity” as a basis for the “rights of man.” Racism accompanied and reinforced the massive colonialist endeavors of imperialist states, as well as internal genocides such that carried out in the United States against indigenous peoples. Since the U.S. Civil War and the abolition of slavery, racism has continued to be used to exclude of a large part of the country’s population, which is treated as “second-class citizens” and “second-class workers.” This promotes internal division within the U.S. working class. In turn, as Black feminists have pointed out, racial oppression and gender oppression are masterfully combined to maximize capitalist profits: it is a fact that there is a larger wage gap for Black and Latina women workers in the United States, just as there is disproportionate institutional and police violence against Black youth. It is also used to support racist and xenophobic policies against migrants in Europe, where they are treated as second-class workers and lack basic social and democratic rights.

5. Marxism and Intersectionality

In Capital, Marx wrote, “Labor cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the black it is branded.” In an earlier work, he and Friedrich Engels had pointed out that “social progress, changes of historical periods, take place in direct proportion to the progress of women towards freedom; and the decline of a social order occurs in proportion to the reduction of women’s freedom”, paraphrasing the utopian socialist Fourier. In The Condition of the Working Class in England, Engels had specifically analyzed the reality of working women who were entering the sphere of capitalist production in large numbers and experiencing the twofold grievances of oppression and exploitation. In The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, Engels continued the incomplete ethnological studies carried out by his friend to develop an analysis of the family institution in history and the oppression of women.

Revolutionary Marxism has analyzed the relationship between exploitation and oppression in other ways as well. For example, Marx and Engels maintained that the English proletariat could not be free if its rights were based on the oppression of Irish workers. Later, Lenin argued that a people that oppresses another people cannot be free, and defended the right to national self-determination as well as the fight against colonial oppression.

In her critique of intersectionality theories, Lise Vogel correctly argues that socialist feminists of the 1960s and 1970s had already highlighted the intersection between patriarchy, racism, and capitalism before the term intersectionality became popular. It is important to note, however, that a long tradition of socialist feminist thought had developed long before that period, from Flora Tristán to Engels and Clara Zetkin, the Russian revolutionaries, and many others. This led to important international socialist women’s conferences and programs and organizations of peasant and working women. The Transitional Program written by Leon Trotsky and adopted by the Fourth International in 1938, includes among its slogans the need to “Open the road to the Woman Worker! Open the Road to the Youth!” and to seek “support among the most exploited layers of the working class.”

Intersectionality theorists often criticize Marxism for what they consider to be “class reductionism.” But defending the centrality of a “class analysis” does not mean limiting it to the activity of unions in wage struggles. That is a corporatist, economist, or narrowly syndicalist perspective of class. It is true that the 20th-century practices of many of the Stalinized Communist parties, as well as the trade union bureaucracies, were based on these narrow corporate politics, thus deepening the divide between “class politics” and the struggle of movements against oppression. But only by falsely equating Stalinism with Marxism is it possible to assert that Marxism has not considered the “intersection” of class exploitation with gender oppression, racism, colonial oppression, and heterosexism.

A class analysis aims to reveal the relationships that structure capitalist society, based not only on the generalized expropriation of surplus value for the accumulation of capital, but also on the appropriation of women’s reproductive work in the home, as well as on the concentration of capital in large monopolies, the expansion of financial capital, and the competition between imperialist states that lead to global wars and plunder. It also examines how capital uses and establishes “differences,” fueling racist, misogynistic, and xenophobic ideologies to maximize exploitation and provoke divisions within the ranks of the working class. This class analysis, far from expressing an “economic reductionist” view, includes the interaction of political and social elements and allows a deeper understanding of the connection between class relations and racism, patriarchy, and heterosexism.

At the same time, it recognizes that if the working class — which in the 21st century is more diverse, racialized, and feminized than ever before — manages to overcome its internal divisions and fragmentation, it has the unique capacity to destroy capitalism and place the entire economy, industry, transport and communications system under its control as the basis for organizing a new society of free producers. The retreat from “class politics” actually means abandoning the struggle against the capitalist system, without which it is impossible to put an end to the terrible injustices caused by exploitation and oppression based on race, gender or sexuality.

Since the capitalist crisis of 2008, with the emergence of new resistance movements against neoliberal policies, some sectors of feminist activists, anti-racist, and the youth movements have been defending the idea of “intersectionality” in a new sense to form coalitions among various oppressed groups. The women’s movement that organized the March 8, 2018, strikes in the Spanish State, for example, has itself as an “anti-capitalist, anti-racist, anti-colonial, and anti-fascist” movement. This was undoubtedly a very important step forward toward the convergence of struggles and a countertrend to the logic of fragmentation. However, the sum or “intersection” of resistance movements is insufficient if they are not connected with a common strategy to defeat capitalism, without which it is impossible to end racism or patriarchal oppression.

It is not about counterposing “movements” or “identities” to an abstract and genderless working class. Never before in history has the working class been so diverse in terms of gender and race. Women already make up 50 percent of the working class, and of that Black, Latin, and Asian women are the majority. The key to a hegemonic strategy, then, is to return to the centrality of class politics that decisively incorporates the fight against all oppression based on gender, race, and sexuality. This means seeking to unite what capitalism divides, strengthening the internal unity of the working class, as well as adopting a policy of alliances with movements that fight against specific oppression. This perspective, along with the fight to expropriate the expropriators, is the only one that will allow progress toward a truly free society.

First published in Spanish on February 24, 2019, in Contrapunto.

Translation by Marisela Trevin

Notes

Notes↑1 Terry Eagleton, Against the Grain: Essays 1975–1985 (London, UK: Verso, 1986).

↑2 Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics,” in Feminist Legal Theory: Readings in Law and Gender, ed. by Katharine T. Bartlett and Rosanne Kennedy (New York, NY: Routledge, 1991).

↑3 Angela Y. Davis, Women, Race, and Class (New York, NY: Knopf, 1981).

↑4 Whether in terms of the radical feminism of Shulamith Firestone in a 1970 essay or the materialist feminism of Cristine Delphy from 1980. See Shulamith Firestone, “The Dialectic of Sex,” in Radical Feminism: A Documentary Reader, ed. by Barbara A. Crow (New York, NY, New York University Press, 2000); Christine Delphy, “The Main Enemy,” Feminist Issues 1, no. 1 (1980): 23–40.

↑5 As formulated by Kate Millet in Sexual Politics: A Surprising Examination of Society’s Most Arbitrary Folly (New York: Doubleday, 1970).

↑6 bell hooks, Feminism Is for Everybody: Passionate Politics (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2000).

↑7 Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness and the Politics of Empowerment (New York, NY: Routledge, 1990), 127.

↑8 Emilio Albamonte and Matías Maiello, “At the Limits of the ‘Bourgeois Restoration,’” Left Voice, December 24, 2019. First published in Spanish in 2011.

↑9 Pratibha Parmar, “Black Feminism: The Politics of Articulation,” in Identity: Community, Culture, Difference, ed. by Jonathan Rutherford (London, UK: Lawrence & Wishart, 1990), 107.

↑10 Terry Eagleton, The Illusions of Postmodernism (Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing, 1996), 22.

↑11 Marta E. Giménez, Marx, Women, and Capitalist Social Reproduction: Marxist Feminist Essays: (Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers, 2019.

Josefina L. Martínez

Josefina is a historian from Madrid and an editor of our sister site in the Spanish State, IzquierdaDiario.es.