Conversation

Ghost in the Machine

Intellectual historian Peter E. Gordon discusses the role of theology and secularization in the work of the Frankfurt School philosophers.Nathan GoldmanMarch 16, 2021

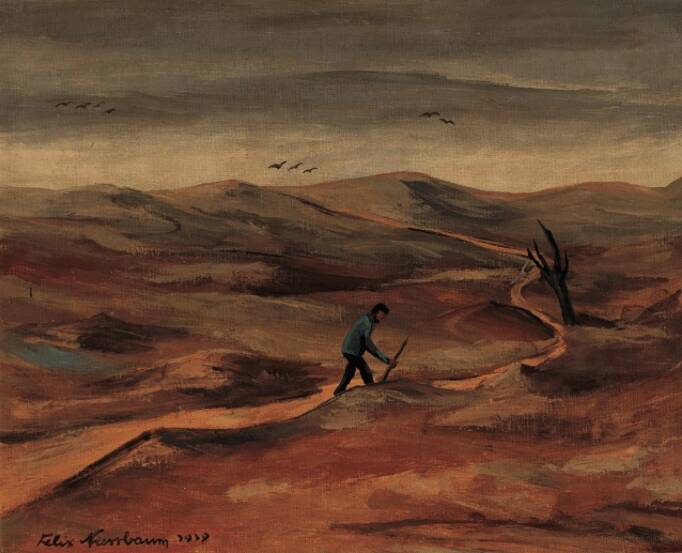

Felix Nussbaum, The Wandering Jew, 1939. Excerpt from the cover of Migrants in the Profane.

Felix Nussbaum, The Wandering Jew, 1939. Excerpt from the cover of Migrants in the Profane. Courtesy of Yale University Press.

In the last fragment of his 1951 book Minima Moralia, one of the foundational texts of critical theory, Theodor Adorno provocatively recasts his own philosophical project in seemingly religious terms. “The only philosophy which can be responsibly practised in face of despair,” he writes in E.F.N. Jephcott’s translation, “is the attempt to contemplate all things as they would present themselves from the standpoint of redemption.” Soon, the theological language grows even more explicit: “Perspectives must be fashioned that displace and estrange the world, reveal it to be, with its rifts and crevices, as indigent and distorted as it will appear one day in the messianic light.” Adorno did not present himself as a religious thinker, yet theological concepts flash up in his work at key moments.

In the spring of 2017, intellectual historian Peter E. Gordon delivered a series of lectures at Yale examining the fraught role of theology and secularization in Adorno’s work, as well as that of his friends and colleagues Walter Benjamin and Max Horkheimer. In his talks, Gordon argued that these thinkers—all major figures in the Frankfurt School, a cohort of influential anti-capitalist German social theorists that emerged in the interwar period—reckon with and transform theological ideas in a variety of compelling ways. Late last year, he released a book adapted from these lectures, Migrants in the Profane: Critical Theory and the Question of Secularization.

In some ways, this book concerned with exile—from its titular image to its interest in the lives of these theorists, all of whom were displaced from Germany during the rise of the Third Reich—marks a homecoming for Gordon. As a graduate student, he studied under the intellectual historian Martin Jay, whose 1973 book The Dialectical Imagination ignited American interest in the Frankfurt School. (Migrants in the Profane is dedicated to Jay.) Gordon’s own scholarly career, however, has been centrally engaged with the ideas of the philosopher Martin Heidegger; his first two books considered Heidegger’s relationships with the Jewish theologian Franz Rosenzweig and the neo-Kantian philosopher Ernst Cassirer, respectively. His 2016 book Adorno and Existence, on Adorno’s generative critique of phenomenology and existentialism, served as Gordon’s bridge back to the Frankfurt School after “many years in the Heideggerian wilderness,” as he writes in the acknowledgments to Migrants in the Profane.

Through close, creative readings of Benjamin, Horkheimer, and Adorno, Gordon’s latest book pursues these thinkers’ relationship to religious concepts and secularization, along with broader questions about their epoch and ours. “Does secularization mean the disappearance of religion or its transformation?” he asks in the book’s introduction. “In the modern era can religious concepts survive or are they irrevocably lost? Can religious concepts retain both their relevance and their validity in a secular age, or is the dissolution of religion a philosophical and political necessity if we are to think of ourselves as truly modern?”

I spoke with Gordon about these thinkers’ varied attempts to reckon with religion and secularization and the relationship between theology and social critique. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Nathan Goldman: How did you become interested in secularization?

Peter E. Gordon: Some years ago, I wrote a long

review of [the philosopher] Charles Taylor’s book A Secular Age. I have enormous admiration for Taylor, but I quarreled with his book quite a bit—and it was partly due to my quarrels that I felt moved to start developing my own thoughts on secularization. The concept interests me in part because it unites philosophical themes and themes in social theory. And I found it especially intriguing that it figures prominently, and in very complex ways, in the writings of some members of the first generation of Frankfurt School critical theorists—Walter Benjamin, Max Horkheimer, and Theodor Adorno.

In fact, Adorno suggests that in order to properly understand what’s happened in the modern philosophical tradition, we need to attend to the way theological concepts have been transformed and secularized. For instance, he thinks that Martin Heidegger’s thought represents a kind of pseudo-theology without God. In his little polemical book The Jargon of Authenticity, he talks about the way existential motifs in postwar Germany [influenced in part by Heidegger’s earlier work] bear witness to a gesture of sanctification without a sanctifying factor—which is to say, there’s this aura of the sacred even though there’s no source of the sacred.

I’ve found a great deal of instruction in the philosophy of [second-generation Frankfurt School theorist] Jürgen Habermas. He has long had an interest in the problem of secularization, but more recently he’s turned in a far more decisive way to the question of how secular societies might continue to draw moral and political instruction from religion without sacrificing their commitments to a secular framework for democratic life. It’s that question that I find most intriguing.

NG: In your chapter on Walter Benjamin, you draw on this perplexing claim from the philosopher’s unfinished opus, The Arcades Project: “My thinking is related to theology as blotting pad is related to ink. It is saturated with it.” You argue that “Benjamin conceived of his work as the secularized trace of theological ideas.” How do you understand the role of theology in Benjamin’s thinking? Where do you see the problems with his use of religious concepts?

PEG: In one of Benjamin’s last works, his “Theses on the Philosophy of History”—one of his attempts to develop some kind of syncretism of Marxism and religion—he invoked the curious image of the chess-playing mechanical Turk, which was a contraption presented at the Viennese court by an engineer named Wolfgang von Kempelen. The machine was a sham; it turned out there was someone hidden inside. Benjamin reads the device as an allegory for [the Marxist concept of] historical materialism. Like the chess-playing Turk, historical materialism is supposed to win all the time—which is to say, it’s supposed to offer an adequate explanation for developments in history. But Benjamin says it can’t do that unless it draws upon the energies and concepts of theology, particularly the concept of historical rupture, or what he calls “messianic time.” So Benjamin says, quite cleverly, that the person hidden within the so-called automaton, the chess-playing Turk, is like theology concealed within the inanimate apparatus of historical materialism. In other words, historical materialism can only win—it can only explain history—if it draws upon the hidden powers of theology.

My argument would be that this formulation founders in a kind of paradox. Historical materialism, after all, has to explain that the movements of history are due to the immanent contradictions of history itself. Benjamin's argument, however, is that historical materialism must appeal to an extra-historical force that bursts into history, as if from the outside. That violates what would seem to be the central principle of historical materialism. And I therefore find [Benjamin’s argument] curious, fascinating, intriguing—but not philosophically defensible.

NG: For you, Adorno succeeds where Benjamin fails in reconciling the sacred and the profane (and perhaps where Horkheimer never really attempts to reconcile them). How do you see the relationship between these attempts, and why does Adorno’s method take him further?

PEG: I think that Adorno proved somewhat more successful and that his position might hold greater promise. In a few places in his work, Adorno makes reference to the idea that theological concepts cannot persist in their original, robustly metaphysical form, and that they can only survive if they undergo what he calls “a migration into the secular,” or the profane. This is where I got the title of my book, capitalizing on Adorno’s metaphor and even applying it to the theorists themselves, describing them as “migrants in the profane.” Of course, that’s partly due to the fact that all three of them were touched by the history of fascism: Benjamin [fled Germany and ultimately] committed suicide, and Horkheimer and Adorno went into exile [in the United States], although they both returned to Germany after the war. But as I see it, the figure of migration is an important one not just for understanding their biographies, but also for understanding their thought. Adorno in particular takes up the theme of exile or what does not belong as a kind of philosopheme—a philosophical figure for what persists as the negative within any social whole.

To me, Adorno’s intriguing phrase about migration into the profane encapsulates his contribution to debates over secularization. It’s as if he means to say that any concept must pass through a trial of secularization. It can still remain, in some sense, philosophically effective, but it does undergo a kind of transformation. In my chapter on Adorno I explore that idea, and along the way I develop an almost fanciful comparison between Adorno’s negative dialectics and the philosophical gestures that we associate with negative theology [seeking knowledge of God subtractively, by means of what cannot be said about the divine]. I take Maimonides as my exemplar of the latter. Adorno and Maimonides both pursue the via negativa, prosecuting positive claims in order to arrive at a higher understanding. Maimonides negates predicates about God in order to arrive at a higher understanding of God. Adorno pursues the via negativa because the negative is a way of shattering the power of ideology—and therefore, negation becomes itself a path toward higher understanding. I explore that comparison as far as it goes—though in a crucial moment, the comparison breaks down: Adorno borrows the critical energies of negation from theology, but uses them without restraint, pursuing them even into the heart of the last remaining metaphysical concept—the concept of God—and dissolves that concept of its reality, too.

This, it seems to me, is the best way of understanding that famous phrase by Adorno at the very end of Minima Moralia, where he says that besides the demand that is placed upon thought, the reality or irreality of the concept of redemption hardly matters at all. He believes that the concept of redemption—which in his thinking doesn’t enjoy any robust, metaphysical status—serves purely negative or critical purposes.

NG: You’re careful to trouble attempts to categorize Adorno—who had a Jewish father and was affected by Nazi race laws, but didn’t consider himself Jewish—as a Jewish thinker. But you also draw out aspects of his relationship to Jewish thinking, including making a fascinating connection between Lurianic Kabbalah and the conclusion of Adorno’s book Negative Dialectics. How does that connection exhibit Adorno’s way of resolving the sacred into the profane?

PEG: Adorno was not deeply versed in Jewish mysticism, and I believe he absorbed what he knew of it almost exclusively through the instruction he received from Gershom Scholem [the scholar who founded the modern study of Kabbalah]. He and Scholem met in the 1920s, and regarded each other with some suspicion. Scholem seems to have really disliked Adorno—he even went so far as to suggest that Adorno’s first book on Kierkegaard had subtly plagiarized from Benjamin’s study of German baroque tragedy. They met again in New York, when Adorno had fled Europe and was living there, and once again, their relations were somewhat strained, but they kept up an intermittent correspondence and began to develop a kind of friendship, in part because they were both traumatized by Benjamin’s death. In the postwar years they became guardians of his flame and assumed an important role in collecting and publishing his letters from around the globe, and overseeing some of the earliest collected editions of his writings.

Now, Adorno and Scholem’s own correspondence is instructive because we can see both how different they are and how they came to share certain ideas, or pushed each other in interesting ways. Scholem often tried to encourage Adorno to recognize theological motifs in his own work. Adorno resisted these suggestions, but I think was prompted to take them seriously, and one can see how Scholem’s influence left its mark particularly in Adorno’s last great philosophical work, Negative Dialectics. In the conclusion to this book, Adorno describes the way mystical traditions in religion—he discusses both Judaism and Christianity—attend to this-worldly life: to immanence, not just transcendence. The mystical tradition has always understood that this-worldly existence must be the space in which we realize our hopes for redemption.

And this brings him to what I regard as the most pertinent argument concerning secularization. Adorno says the concept of God itself is, paradoxically, a concept of something that resists conceptualization. It’s the concept of something that doesn’t fit into immanent categories of understanding. And for Adorno, that concept of what does not fit—that concept of something that exceeds our rational grasp—needs to be mobilized and secularized into our own critical practice. He says that the concept of God has undergone a shift of terrain into the mundane realm, where it has become a postulate that we use in order to explode the false appearance of the world as a seamless whole. The world presents itself to us as if it is complete, rational, and justified, but we can use the theological concept of what does not fit as a postulate for our own critical practice in order to explode that false totality and expose the riffs or crevices within the world, the [marks] of negativity. So a theological concept, once it migrates into the profane, becomes an important guide for social criticism.

NG: I wonder whether we can learn anything from these thinkers about secular interest in religious practices in addition to concepts. Does Adorno’s absorption of religious concepts into the philosophical work of negation, or Benjamin’s attempt to produce what you call “the secularized trace of theological ideas,” teach us anything about what’s at play in religious rituals, when practiced despite the negation or abandonment of their transcendent content?

PEG: Judaism is rather distinctive in that it places such a great emphasis on religious practices, often to the exclusion of any great worry about belief commitments. If you go into any shul, the number of people there who will say they believe in God might be rather minimal, but they’re all there participating in observance. Interestingly, it seems any concern with halachic practice has now become secondary to one’s commitments to the State of Israel—today Spinoza might never have been expelled from the Jewish community for his identification of God with nature, but had he said one word against Zionism, the herem would have been pronounced again.

I do think Judaism raises a very intriguing question as to what can be learned philosophically from practices, or what they tell us about the contribution that religion might or might not be able to make to the wider world. Sociologists have long been interested in religious practices, and the ways communities use these practices to re-enact the character of the social bond itself, reconfirming what it is to be a member of the group. Emile Durkheim developed that theme in his study of Australian religious rites. Quite recently, Habermas has developed it as well: His view seems to be that there’s something very special about religious practices—that they nourish some understanding of values that transcend mundane life.

But I think we should be skeptical about the claim that religious communities sustain a privileged understanding of metaphysical categories. This relates to my disagreement with my colleague Martin Hägglund, who wrote a very interesting philosophical reflection on religion, the secular, and socialism called This Life. Hägglund insists that religion always directs our attention away from this world toward the afterlife, or eternal life. In my

review of his book I pointed out that this doesn’t capture the way many religions think about this life. Judaism, again, seems to me a form of religious practice that can be detached from many metaphysical concerns—for example, whether there is an afterlife at all. I think most Jews today remain rather agnostic on that point. Even Maimonides said that the ultimate redemption of the world would involve the resurrection of the dead: One doesn’t go to heaven; the dead come back here.