Thu, July 14, 2022

Gen Erjavec conducts COVID-19 wastewater monitoring outside Risley Hall, a residence at Dalhousie University. The City of Moncton has been doing its own COVID-19 wastewater testing in partnership with Dalhousie University since fall 2020. (Submitted by Graham Gagnon - image credit)

Public Health officials have raised questions around whether some COVID-19 cases in New Brunswick went undetected in early 2021, after an apparent mismatch between the amount of COVID-19 appearing in wastewater and the province's own COVID-19 testing.

The wastewater data shows four apparent spikes of COVID-19 in 2021: on Feb. 8, March 18, April 29 and June 28, all times when there were "minimal cases or positive tests" reported and PCR testing was widely offered.

The wastewater testing is conducted by the City of Moncton, which has a partnership with Dalhousie University, and is provided to New Brunswick Public Health. CBC News obtained a copy of the test results, and discussion within the Department of Health about the results, through access to information.

Emails from this past April show health officials tried to find an explanation for the differences in the 2021 data, such as increased occupancy at hotels around March break, a difference in the boundaries between the health zone and the area covered by the wastewater treatment plant, and the role of temporary foreign workers who were quarantining in local hotels.

But they couldn't find an easy answer.

'Things do not seem to be lining up'

"The points that you have mentioned are all things that we have considered, but things do not seem to be lining up," Shannon LeBlanc, the manager of surveillance for the Department of Health, wrote in an April 7, 2022 email.

"We have taken into accounts cases in areas outside of Moncton, and cases among the temporary foreign worker population. It is possible that we had cases that went undetected (how many is not clear)."

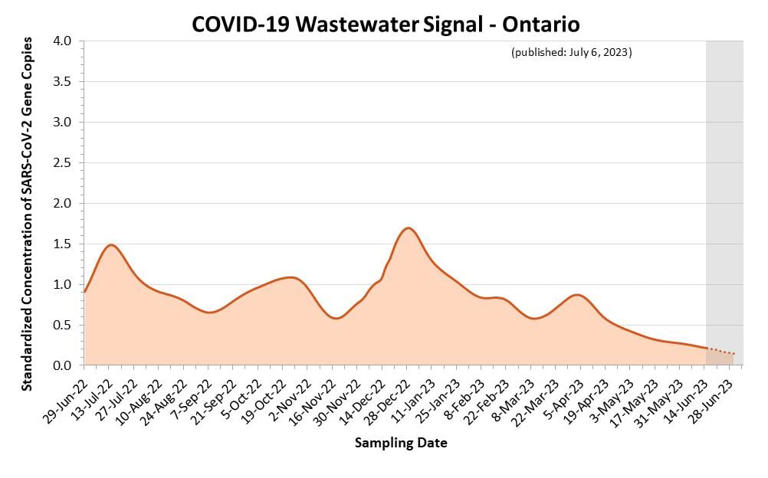

Duk Han Lee/CBC News Graphics

No one from Public Health was made available for an interview to explain the apparent mismatch.

In an emailed statement, Department of Health spokesperson Valerie Kilfoil said the government is still assessing the benefits of the wastewater testing pilot in Moncton.

"The materials provided to you should be considered working documents – not a formal surveillance program by the province," Kilfoil wrote.

She didn't provide any explanation about why the data seemed to show some cases of COVID-19 went undetected.

Raywat Deonandan said the province shouldn't dismiss the wastewater results.

"It is so objective, more so than PCR testing, that I think we have to hang our hats on it more confidently," said Deonandan, who is an epidemiologist and associate professor in the faculty of health sciences at the University of Ottawa.

Without widespread random testing, which can capture people who are asymptomatic, Deonandan said it's common to under-detect COVID-19 cases.

"If random testing is not being done, as it isn't anywhere frankly, the PCR testing is not a good indication of the true extent of disease burden," Deonandan said.

"That's why I would err on the side of wastewater data to get a true sense of prevalence, not on PCR testing data."

Most provinces in Canada aren't detecting the full scope of COVID-19 infections because there's not enough testing being done, according to Tara Moriarty, an associate professor and infectious disease researcher at the University of Toronto.

New Brunswick offered widespread PCR testing in early 2021, but PCR tests are now only available to people over age 50 or under age two, people who are pregnant or immunocompromised, or people who work in a vulnerable setting, such as a hospital.

"We tend to prioritize testing for people who are higher risk," Moriarty said.

"So that means that we sometimes do have quite a few more infections than we think, as would be suggested by wastewater data. But we're simply not capturing them because we're not testing enough."

Kilfoil said the province is "no longer seeking to confirm and detect every single case occurring in the province or within specific communities."

Province considering COVID-19 wastewater monitoring

Dalhousie University's Centre for Water Resources Studies has been measuring COVID-19 in wastewater in partnership with the City of Moncton for about 18 months, according to Graham Gagnon, the centre's director.

He said it's not surprising to see a mismatch between the wastewater data and public health's testing data. The two bodies aren't coordinating when collecting their data, so there could be differences in how they're collecting information and reporting it.

CBC

"For the wastewater work that we've done in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, it's been a research scheme, not a public health reporting mechanism," Gagnon said.

"As a result, it was never intended to be coordinated, so you end up with gaps from a wastewater standpoint."

Last month, Chief Medical Officer of Health Dr. Jennifer Russell said the province is considering implementing COVID-19 wastewater monitoring, but didn't provide any details on who will conduct the testing and whether it will sample the entire province or just certain centres.

Other jurisdictions, such as Ottawa Public Health, post results of their COVID-19 wastewater data online. The federal government also has a COVID-19 wastewater surveillance dashboard, but it doesn't include data from New Brunswick.

Deonandan, the epidemiologist, sees value in sharing wastewater testing data with the public.

"This is the kind of thing that should be made publicly available, because we're in an era now where there's so much distrust of authority, that the only way forward is maximum transparency at all times."

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/70743718/GettyImages_1169117045.0.jpg)