Published 08.01.2019

Cambridge University Press

622 Pages

IN 1590, the mathematician and astronomer Thomas Harriot performed a grim calculation. He began with the circumference of the earth and moved on to tally the size and population of England: 50,000 square miles; five million inhabitants. His figures were a little off, but his concern is a strikingly modern one. He was worrying about what we now call “carrying capacity” — the number of people whose life can be supported by the planet. Based upon birth rates and the correct assumption that future lifespans will be longer, Harriot concluded that the outlook was bleak, for in “400 years upon the former suppositions there would be more men than can stand on the face of the whole Earth.” Four hundred years from 1590 is, of course, more or less today. Here is one of those curious moments in which a writer from the distant past appears to be looking directly at our present.

Another example, from a 1598 poem by the clergyman Thomas Bastard: Bastard was a satirist who also wrote poems about overfishing and excessive grazing by sheep, but here his subject is explicitly human. “Our fathers did but use the world before, / And having used, did leave the same to us,” he notes, for our forebears lived more simply than we do now. They were, in a currently fashionable phrase, “good ancestors,” but now, “We spill whatever resteth of their store. / What can our heirs inherit but our curse?” Our heirs, he fears, will curse us for our waste of the earth.

Another example: “My house and barn were taken / One dark night, and all my nuts” begins an anxious red squirrel in Welshman Robin Clidro’s mid-16th-century poem “Marchan Wood.” The rodent continues:

The squirrels all are calling

For the trees; they fear the dog.

Up there remains of the hill wood

Only grey ash of oak trees.

Animals have been speaking in Western literature since Aesop, and 16th-century English poetry is filled with them. Todd Andrew Borlik’s splendid new anthology Literature and Nature in the English Renaissance includes many examples of these garrulous, witty creatures: complaining cats and parrots, a surprisingly sarcastic otter, and a now-extinct fish called a pout singing a rousing protest at the draining of the fens. What is striking is not that the animals are speaking — even in verse — but what they are speaking about: man’s ruin of the natural world, his destruction of natural habitats. That squirrel was right to worry. Despite a series of Elizabethan timber laws, the 16th century saw huge deforestation across England and Wales. In John Lyly’s Love’s Metamorphosis (1601; based on Robert Greene’s 1588 work), a “tree bleeds and groans”; in “A Dialogue between an Oake, and a Man cutting him downe,” a 1653 poem by Margaret Cavendish, the tree protests to the man and laments that it “did invite the Birds to sing, / That their sweet voice might you some pleasure bring.” The scenario is familiar but the language has slightly changed, and the word used at the time to describe such destruction of woodland was “disafforested.” This means two things, both a legal and a practical act: the forest is first stripped of its protected status and then cut down to be sold.

An overpopulated and deforested earth, ruined for future generations; the failure of political and legal solutions to the current crisis: this was how English writers saw their world in 1600. Anachronism is a funny game for literary historians. For the past 25 years, the dominant mood in scholarship on early modern literature has been New Historicist, and what this means is that a generation or two of scholars have been trained to see these old texts as documents of and about the past. But in reading Borlik’s endlessly fascinating anthology, it is hard to avoid the uncanny frisson that what is being here described is not yesterday but today.

Sixteenth-century Europe suffered from a climate crisis. Low temperatures and failed harvests culminated in the great dearth of 1594–’96. In London, there was anti-pollution legislation passed in 1535, 1543, and 1590. Englishmen worried about overfishing and — in 1639 — the melting of the ice caps. In “The Necessity of a Plague” (1603), a satiric celebration of plague as a means to limit overpopulation, Thomas Dekker and Thomas Middleton foreshadowed today’s “dark ecology” movement: “How needful (though how dreadful) are / Purple Plagues or Crimson War.” During the English Civil War (1642–’51), there were calls for widespread vegetarianism, and in all this was a time of ecological worry and protest, which looks startlingly like today.

This is not exactly the story Borlik wishes to tell, however, as instead of circularity he generally sees progress. In his introduction and notes to the anthology, just as in his previous book Ecocriticism and Early Modern English Literature: Green Pastures (2010), he argues that what distinguishes these Renaissance nature narratives is what he calls “a gradual shift away from an anthropocentric worldview.” Where the Bible promised man mastery over the earth and the animals, men in the 16th century began to realize that perhaps the world was not wholly made for them to use and destroy at will. As Borlik tells it, this is a teleological story, in which man learns his diminished place in nature; and in doing so, modern science is born, accumulating heroes (Michel de Montaigne, Margaret Cavendish) and villains (Francis Bacon, René Descartes) along the way.

Simply put, Borlik suggests that anything that smells of anthropocentrism is bad or, at the very least, a little embarrassing. In passing, for example, he chastens the devotional poet George Herbert for his “outrageous anthropocentrism” and praises Montaigne for his “caustic indictments of anthropocentrism.” This is, in a simple form, the argument inside the critical movement known as Ecocriticism, and it attempts to correct what it considers the toxic old habits of human-centered thinking. Such correctives are always valuable, of course, and broadly, this couldn’t be a better time to publish a book that thinks so carefully and sympathetically about climate change and ecological disaster. And yet, in this moment of Greta Thunberg and Extinction Rebellion, the Ecocritical argument — at least in its less rigorous forms — is beginning to look a little naïve.

We are now living, we are repeatedly told, in the Anthropocene, an age defined by man’s impact. As Dipesh Chakrabarty has argued, perhaps most powerfully in his 2009 essay “The Climate of History: Four Theses,” this has consequences also for the traditional assumptions inside the humanities. “In unwittingly destroying the artificial but time-honoured distinction between natural and human histories,” he writes, “climate scientists posit that the human being has become something much larger than the simple biological agent that he or she always has been. Humans now wield a geological force.” He continues: “To call human beings geological agents is to scale up our imagination of the human.”

Borlik’s optimistic narrative of anthropocentric decline sits awkwardly with this sense of man’s radical — even weaponized — centrality to geohistorical events. To put it another way: the idea that climate change has a history is inevitably in slight tension with the insistence upon the exceptionality of our current moment. Perhaps this is the point, and also what is most valuable about Borlik’s anthology: that what we are seeing in these 16th-century texts is not at all an ending but our beginning. Because this was an age of acute literary sensitivity and wild literary experimentation, we can, in the poetry of the time, glimpse what we might have become. It is old words such as “disafforested” and old stories about accusatory animals and enchanted landscapes that might help us in new ways of thinking.

¤

There is little of William Shakespeare in Borlik’s anthology: a poem, a couple of speeches from the plays. This is only sensible, as Borlik’s admirable project is to bring to light forgotten or lesser-known works. After all, Shakespeare’s complete works are themselves a kind of anthology of Renaissance nature writing. The archetypal humanist, Shakespeare’s plays celebrate and embody a radical anthropocentrism. Yet they also repeatedly return to the natural world, to the climate and man’s place within it, which is why they are now so frequently mined by eco-critics in search of literary representations of man’s involvement in the climate and the ecosystem. But this is perhaps insufficient for our current crisis. In the light of today’s storms — and Borlik’s anthology of storms from the past — it is again valuable to try to draw from Shakespeare that most old-fashioned, even Victorian, of cultural resources: moral lessons in canonical literary works.

Shakespeare was the great poet of disrupted weather. There is the unusually hot day in Romeo and Juliet when the fight breaks out between Romeo and Tybalt; there are the disrupted seasons and rotten harvests of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, with

Contagious fogs which, falling in the land,

Hath every pelting river made so proud

That they have overborne their continents.

There is the storm in King Lear:

You sulphurous and thought-executing fires,

Vaunt-couriers to oak-cleaving thunderbolts,

Singe my white head!

In each case, the wild weather is imagined as attached to human cause or as offering a direct lesson to the human characters. In these plays, man is tied to the weather: “minded like the weather,” in the phrase of King Lear.

You can say anything about Shakespeare (that is why people keep doing so), but it is hard to avoid the impression that the climate and the seasons are significant, and that their significance is directed at man. In Julius Caesar, wild storms and lightning accompany political unrest in Rome. Casca has seen the foaming oceans and the scolding winds and he warns:

let not men say,

“These are their reasons; they are natural”;

For, I believe, they are portentous things

Unto the climate that they point upon.

Thanks to Borlik’s anthology, we are reminded of how much Shakespeare was a poet of his own time of natural crisis. But there is something more than this: his concerns are also ours, and he is most timely in the urgent idea that man must learn from the weather. Above all, we must not look away with a shrug, saying, “But this is only nature.”

During the Renaissance, natural science often worked hand in hand with theology, which is why — as Borlik notes — biology and naturalism were often conducted by clergymen. This seems like the relic of an older arrangement of thought, but the notion that moral questions are at the heart of the scientific inquiry is one we are now returning to. The current discussion of climate change has an oddly religious cast: it has its pieties, its heresies, its apocalyptic strain; it has its moral attitudes even when it looks most directly at science. In Shakespeare’s plays, as in the anthology’s many texts, the natural world is full of such morals; there are, what Duke Senior in As You Like It calls, “Sermons in stones.” The animals are often fantastical — “Spring-headed Hydras,” “Bright Scolopendraes,” “Mighty Monoceroses” — but they are part of an ecosystem of parables that have come to correct and to teach. “Do you require Prudence? Regard the Ant. Do you desire Justice? Regard the Bee,” instructs entomologist Thomas Moffett in “The Theatre of Insects” (1589). Wonder at the natural world is here an engine for environmental activism. William Lawson’s arboricultural treatise “The Size and Age of Trees” (1618) insists: “What living body have you greater than of trees?”

What is perhaps most valuable here — and almost certainly most urgent — is the suggestion of a style of magical thinking: a thinking in parables and allegories, in seeing nature as instructive, as corrective, as always tied to man. Everything is double. The landscape is both allegory and location: it is simultaneously the “Slough of Despond” (John Bunyan, 1678) and drained fenland, and the polluted air is filled with both the noxious smoke from burning sea coal and the “Mist of Error” (Thomas Middleton, 1613). When William Davenant complains in 1656 that “London is smothered with sulph’rous fires,” he is seeing in London a polluted modern city and also a vision of hell; and the word pollution always has this double meaning: it is sin and smog. The weather is both political and physical. One writer suggests that dirty smoke over London caused the English Civil War. For another, comets are both the portent of the fall of kings and a cause of sickness. The clergyman William Barlow published a series of “Dearth” sermons in 1596. “The desire of private gain provoketh God his wrath,” he thundered: “when men prefer the increase of their own commodities before the glory of God, the propagation of his word, or the public benefit.” Anti-capitalist protest is grafted onto Christian piety, and there is little in this portrayal of a fallen world of rotten economics and polluted politics that the activists of Extinction Rebellion would find objectionable.

What we are thinking about here is parables, so let us end in a parable. Men used to see the weather as moral and political, as symbol and as sermon. Then we stopped. We put down our plows, we picked up our phones. We mocked our ancestors for thinking that the weather meant anything, for thinking that plague was spread by sin and not by fleas. We call this mockery modernity. And now, just as Shakespeare promised, and just as the preachers and poets always knew, the weather is moral and political once more.

¤

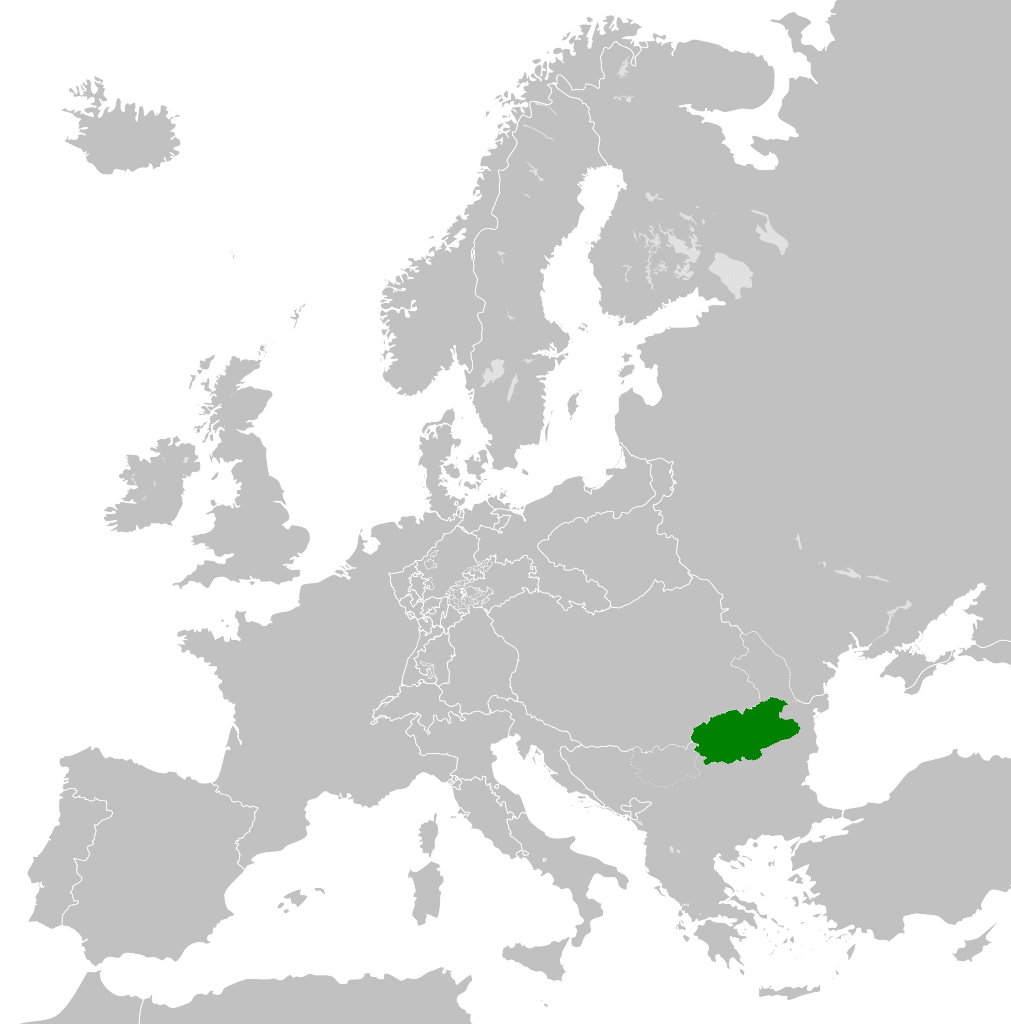

Wallachia

Wallachia