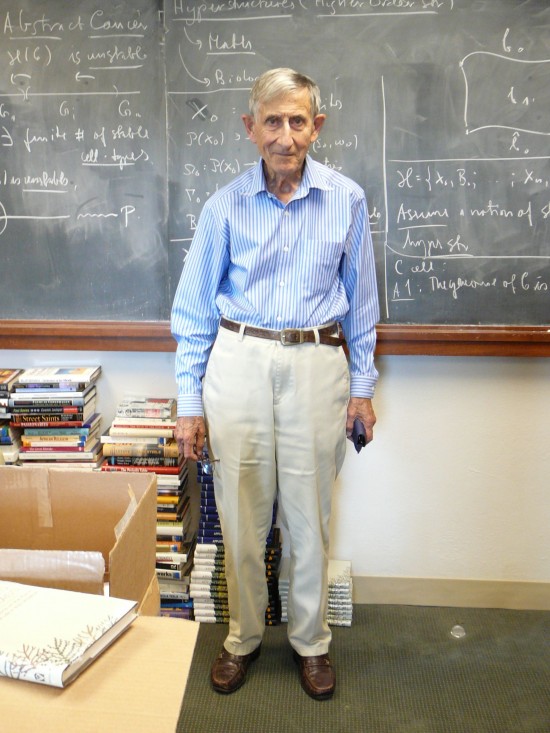

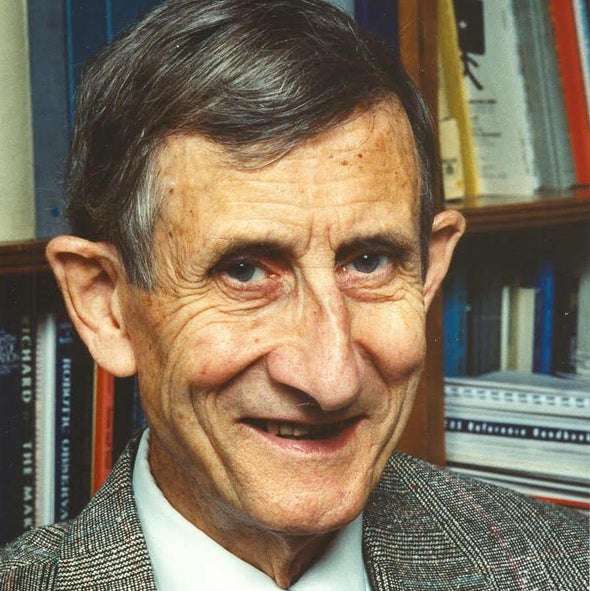

Freeman Dyson in his own words

One of the 20th century’s foremost physicists died today.

by Konstantin Kakaes

Feb 28, 2020

WIKIMEDIA

Freeman Dyson died today, at age 96. He was one of the foremost physicists of his generation, and also wrote widely on the relationships between science, technology, and the world. He wrote occasionally for the New Yorker in the 1970s and 1980s, and, for many years, was a frequent contributor to the New York Review of Books. He also wrote a handful of articles for MIT Technology Review, including a two-part series about his role in World War II.

Here are some selected quotes from his prolific writing. They are by no means representative of the entire range of his interests, but are simply glimpses into a lively, perceptive mind that the world lost today.

On the space race, from a letter to his family in England, January 1, 1958:

"I have nothing original to say about Sputniks. I feel cheerful about them. It seems to me clear that the Soviet government does not intend to throw bombs at anybody but does intend to dominate the earth by rapid scientific and industrial growth. This will in turn stimulate the Americans to undertake major projects which they would be too parsimonious to do otherwise. There is no question that colonization of the moon and planets will be one of them. I expect eventually to take a hand in this. The prospect seems to me exciting and hopeful.”

On technology and ideology, from Disturbing the Universe, the New Yorker, August 6, 1979:

“Scientists are not the only people who play with intellectual toys that suddenly explode and cause the crash of empires. Philosophers, prophets, and poets do it, too. In the long run, the technological means that scientists place in our hands may be less important than the ideological ends to which these means are harnessed. Technology is powerful, but it does not rule the world.”

On genetic engineering, from Infinite in All Directions, 1985:

“I do not think that the theoretically possible dangers of genetic engineering will turn out to be real. I think that the benefits of it will be large and important ... Instead of destroying tropical forests to make room for agriculture, we could leave the forests in place while teaching the trees to synthesize a variety of useful chemicals. Huge areas of arid land could be made fruitful either for agriculture or for biochemical industry. There are no laws of physics and chemistry which say that potatoes cannot grow on trees.”

On the spiritual value of science, from “The Scientist as Rebel,” New York Review of Books, May 25, 1995:

“Historians who believe in the transcendence of science have portrayed scientists as living in a transcendent world of the intellect, superior to the transient, corruptible, mundane realities of the social world. Any scientist who claims to follow such exalted ideals is easily held up to ridicule as a pious fraud. We all know that scientists, like television evangelists and politicians, are not immune to the corrupting influences of power and money. Much of the history of science, like the history of religion, is a history of struggles driven by power and money. And yet this is not the whole story. Genuine saints occasionally play an important role, both in religion and in science. Einstein was an important figure in the history of science, and he was a firm believer in transcendence. For Einstein, science as a way of escape from mundane reality was no pretense. For many scientists less divinely gifted than Einstein, the chief reward for being a scientist is not the power and the money but the chance of catching a glimpse of the transcendent beauty of nature.”

On nuclear energy, from Imagined Worlds, 1998:

“They wrote the rules of the game so that nuclear energy could not lose. The rules for cost-accounting were written so that the cost of nuclear electricity did not include the huge public investments that had been made to develop the technology and to manufacture the fuel. The rules for reactor safety were written so that the type of light-water reactor originally developed by the United States Navy for propelling submarines was by definition safe. The rules for environmental cleanliness were written so that the ultimate disposal of spent fuel and worn-out machinery was left out of consideration. With the rules so written, nuclear energy confirmed the beliefs of its promoters. According to these rules, nuclear energy was indeed cheap and clean and safe. The people who wrote the rules did not intend to deceive the public. They deceived themselves, and then fell into a habit of suppressing evidence that contradicted their firmly held beliefs.”

On evolution and free will, from Origins of Life, 1999:

“As the grandfather of a pair of five-year-old identical twins, I see every day the power of the genes and the limits to that power. George and Donald are physically so alike that in the bathtub I cannot tell them apart. They not only have the same genes but have shared the same environment since the day they were born. And yet, they have different brains and are different people. Life has escaped the tyranny of the genes by evolving brains with neural connections that are not genetically determined. The detailed structure of the brain is partly shaped by genes and environment and is partly random. Earlier, when the twins were two years old, I asked their older brother how he tells them apart. He said, ‘Oh, that’s easy. The one that bites is George.’ Now that they are five years old, George is the one who runs to give me a hug, and Donald is the one who keeps his distance. The randomness of the synapses in their brains is the creative principle that makes George George and Donald Donald ... George and Donald are different people because they started life with different random samples of neurological junk in their heads. The weeding out of the junk is never complete. Adult humans are only a little more rational than five-year-olds. Too much weeding destroys the soul."

Credit:

Credit: