by Bob Yirka , Phys.org

Credit: CC0 Public Domain

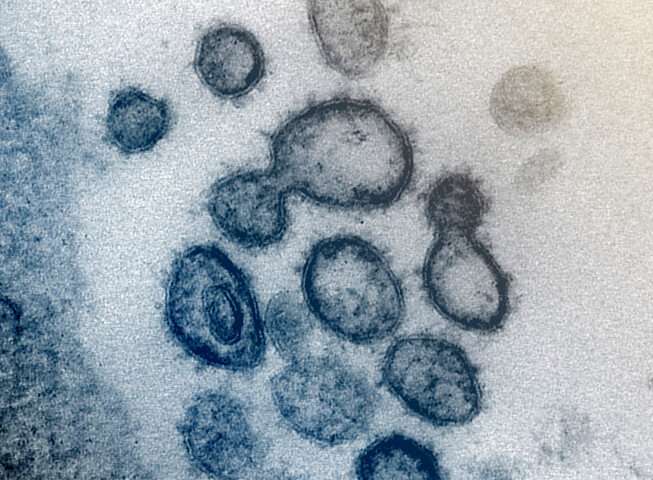

A team of researchers from the University of Tasmania has found evidence of microplastics in ice cores collected off the coast of Antarctica. In their paper published in the journal Marine Pollution Bulletin, the group describes their study of the cores and the plastics they found.

Last year, a team of researchers found examples of microplastics in Arctic ice floes, further evidence of the spread of the pollutants in the world's oceans. In this new effort, the team in Tasmania has found evidence of microplastics in ice cores collected in Antarctica ten years ago.

The cores were collected as part of work dedicated to better understanding the Antarctic—they were taken from sites approximately 2 kilometers from the Antarctic coast and have been in storage at a facility in Hobart, Tasmania, awaiting analysis. The cores were from ice that forms around the coast and thus, unlike pack ice, does not move.

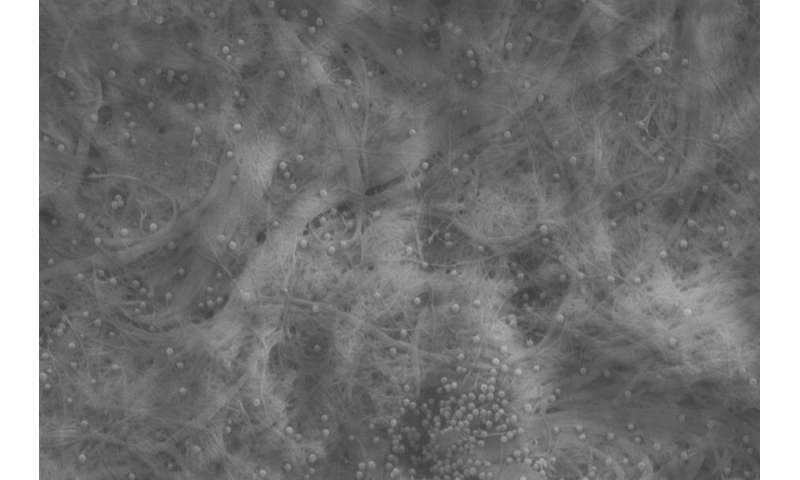

Study of the cores (which were 1.1 meters long and 14 cm wide) revealed 96 particles from 14 kinds of microplastic, with an average of 12 pieces per liter of water—all of the particles were 5 mm or shorter. The most common type was polyethylene, which is used in a wide variety of products. The finding was the first for Antarctic ice—prior studies had found microplastics in water, snow and sediment.

The researchers also noted that the microplastic particles were surrounded by algae, a finding that suggests they may be eaten by krill, which feed on sea ice. And that further suggests that the particles are being consumed by whales when they eat the krill.

The source of the microplastics is not known, though the researchers suggest their size indicates that they are from relatively local sources. The longer microplastics remain in the sea, the smaller they become. They note that the ice cores were taken from the eastern side of the continent, which is visited less often than the west side. They suggest it is likely ice in more highly traveled areas has more microplastic particles in it. They also note that prior studies have shown that microplastics in ice can lead to melting due to heat absorption.

Explore further Microplastics from ocean fishing can 'hide' in deep sediments

A team of researchers from the University of Tasmania has found evidence of microplastics in ice cores collected off the coast of Antarctica. In their paper published in the journal Marine Pollution Bulletin, the group describes their study of the cores and the plastics they found.

Last year, a team of researchers found examples of microplastics in Arctic ice floes, further evidence of the spread of the pollutants in the world's oceans. In this new effort, the team in Tasmania has found evidence of microplastics in ice cores collected in Antarctica ten years ago.

The cores were collected as part of work dedicated to better understanding the Antarctic—they were taken from sites approximately 2 kilometers from the Antarctic coast and have been in storage at a facility in Hobart, Tasmania, awaiting analysis. The cores were from ice that forms around the coast and thus, unlike pack ice, does not move.

Study of the cores (which were 1.1 meters long and 14 cm wide) revealed 96 particles from 14 kinds of microplastic, with an average of 12 pieces per liter of water—all of the particles were 5 mm or shorter. The most common type was polyethylene, which is used in a wide variety of products. The finding was the first for Antarctic ice—prior studies had found microplastics in water, snow and sediment.

The researchers also noted that the microplastic particles were surrounded by algae, a finding that suggests they may be eaten by krill, which feed on sea ice. And that further suggests that the particles are being consumed by whales when they eat the krill.

The source of the microplastics is not known, though the researchers suggest their size indicates that they are from relatively local sources. The longer microplastics remain in the sea, the smaller they become. They note that the ice cores were taken from the eastern side of the continent, which is visited less often than the west side. They suggest it is likely ice in more highly traveled areas has more microplastic particles in it. They also note that prior studies have shown that microplastics in ice can lead to melting due to heat absorption.

Explore further Microplastics from ocean fishing can 'hide' in deep sediments

More information: A. Kelly et al. Microplastic contamination in east Antarctic sea ice, Marine Pollution Bulletin (2020). DOI: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111130

Journal information: Marine Pollution Bulletin

© 2020 Science X Network