Exclusive: Australian researchers query origin of data used for Lancet study, but stress there is no evidence drug is a safe or effective treatment

BEING FROM DOWN UNDER MAY EXPLAIN HAVING THEIR HEADS UP THEIR ASSES

Melissa Davey THE GUARDIAN Thu 28 May 2020

Melissa Davey THE GUARDIAN Thu 28 May 2020

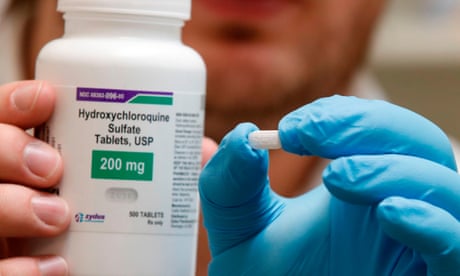

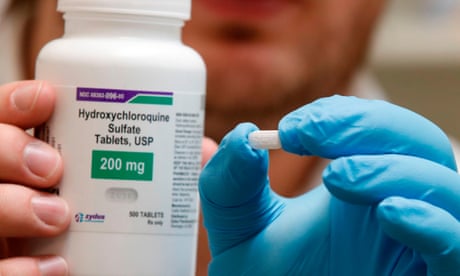

Earlier this week, the World Health Organization said it would temporarily drop hydroxychloroquine from its global study into experimental coronavirus treatments after safety concerns. Photograph: George Frey/Reuters

Questions have been raised by Australian infectious disease researchers about a study published in the Lancet which prompted the World Health Organization to halt global trials of the drug hydroxychloroquine to treat Covid-19.

The study published on Friday found Covid-19 patients who received the malaria drug were dying at higher rates and experiencing more heart-related complications than other virus patients. The large observational study analysed data from nearly 15,000 patients with Covid-19 who received the drug alone or in combination with antibiotics, comparing this data with 81,000 controls who did not receive the drug.

The findings prompted researchers from around the world to reassess their own clinical trials of the drug for preventing and treating Covid-19. The World Health Organization halted all its trials involving hydroxychloroquine due to the concerns raised in the study about its efficacy and safety. It was once viewed as among the most promising medicines to treat the virus, though no study to date has found this to be the case, and the drug can have toxic side-effects. The Australian Department of Health had been stockpiling millions of doses of the drug in case clinical trials found it proved useful.

Australian hydroxychloroquine trial to treat Covid-19 under review after WHO safety concern

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/26/australian-hydroxychloroquine-trial-under-review-world-health-organization-concern-over-safety

Questions have been raised by Australian infectious disease researchers about a study published in the Lancet which prompted the World Health Organization to halt global trials of the drug hydroxychloroquine to treat Covid-19.

The study published on Friday found Covid-19 patients who received the malaria drug were dying at higher rates and experiencing more heart-related complications than other virus patients. The large observational study analysed data from nearly 15,000 patients with Covid-19 who received the drug alone or in combination with antibiotics, comparing this data with 81,000 controls who did not receive the drug.

The findings prompted researchers from around the world to reassess their own clinical trials of the drug for preventing and treating Covid-19. The World Health Organization halted all its trials involving hydroxychloroquine due to the concerns raised in the study about its efficacy and safety. It was once viewed as among the most promising medicines to treat the virus, though no study to date has found this to be the case, and the drug can have toxic side-effects. The Australian Department of Health had been stockpiling millions of doses of the drug in case clinical trials found it proved useful.

Australian hydroxychloroquine trial to treat Covid-19 under review after WHO safety concern

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/26/australian-hydroxychloroquine-trial-under-review-world-health-organization-concern-over-safety

The study, led by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Center for Advanced Heart Disease in Boston, examined patients in hospitals around the world, including in Australia. It said researchers gained access to data from five hospitals recording 600 Australian Covid-19 patients and 73 Australian deaths as of 21 April.

But data from Johns Hopkins University shows only 67 deaths from Covid-19 had been recorded in Australia by 21 April. The number did not rise to 73 until 23 April. The data relied upon by researchers to draw their conclusions in the Lancet is not readily available in Australian clinical databases, leading many to ask where it came from.

The federal health department confirmed to Guardian Australia that the data collected on notifications of Covid-19 in the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System was not the source for informing the trial.

Guardian Australia also contacted the health departments of Australia’s two most populous states, New South Wales and Victoria, which have had by far the largest number of Covid-19 infections between them. Of the Australian deaths reported by 21 April, 14 were in Victoria and 26 in NSW.

Victoria’s department confirmed the study’s results relating to the Australian data did not reconcile with the state’s coronavirus data, including hospital admissions and deaths. The NSW Department of Health also confirmed it did not provide the researchers with the data for its databases.

The Lancet told Guardian Australia: “We have asked the authors for clarifications, we know that they are investigating urgently, and we await their reply.” The lead author of the study, Dr Mandeep Mehra, said he had contacted Surgisphere, the company that provided the data, to reconcile the discrepancies with “the utmost urgency”. Surgisphere is described as a healthcare data analytics and medical education company.

In a statement, Surgisphere founder Dr Sapan Desai, also an author on the Lancet paper, said a hospital from Asia had accidentally been included in the Australian data.

“We have reviewed our Surgisphere database and discovered that a new hospital that joined the registry on April 1, and self-designated as belonging to the Australasia continental designation,” the spokesman said. “In reviewing the data from each of the hospitals in the registry, we noted that this hospital had a nearly 100% composition of Asian race and a relatively high use of chloroquine compared to non-use in Australia. This hospital should have more appropriately been assigned to the Asian continental designation.”

He said the error did not change the overall study findings. It did mean that the Australian data in the paper would be revised to four hospitals and 63 deaths,.

Dr Allen Cheng, an epidemiologist and infectious disease doctor with Alfred Health in Melbourne, said the Australian hospitals involved in the study should be named. He said he had never heard of Surgisphere, and no one from his hospital, The Alfred, had provided Surgisphere with data.

“Usually to submit to a database like Surgisphere you need ethics approval, and someone from the hospital will be involved in that process to get it to a database,” he said. He said the dataset should be made public, or at least open to an independent statistical reviewer.

“If they got this wrong, what else could be wrong?” Cheng said. It was also a “red flag” to him that the paper listed only four authors.

“Usually with studies that report on findings from thousands of patients, you would see a large list of authors on the paper,” he said. “Multiple sources are needed to collect and analyse the data for large studies and you usually see that acknowledged in the list of authors.”

He stressed that even if the paper proved to be problematic, it did not mean hydroxychloroquine was safe or effective in treating Covid-19. No strong studies to date have shown the drug is effective. Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine have potentially severe and even deadly side effects if used inappropriately, including heart failure and toxicity. Other studies have found the drug is associated with higher mortality when given to severely unwell Covid-19 patients.

Australian doctors warned off after prescribing potentially deadly Covid-19 trial drug to themselves TOLD YA, HEADS UP THEIR ASSES

But data from Johns Hopkins University shows only 67 deaths from Covid-19 had been recorded in Australia by 21 April. The number did not rise to 73 until 23 April. The data relied upon by researchers to draw their conclusions in the Lancet is not readily available in Australian clinical databases, leading many to ask where it came from.

The federal health department confirmed to Guardian Australia that the data collected on notifications of Covid-19 in the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System was not the source for informing the trial.

Guardian Australia also contacted the health departments of Australia’s two most populous states, New South Wales and Victoria, which have had by far the largest number of Covid-19 infections between them. Of the Australian deaths reported by 21 April, 14 were in Victoria and 26 in NSW.

Victoria’s department confirmed the study’s results relating to the Australian data did not reconcile with the state’s coronavirus data, including hospital admissions and deaths. The NSW Department of Health also confirmed it did not provide the researchers with the data for its databases.

The Lancet told Guardian Australia: “We have asked the authors for clarifications, we know that they are investigating urgently, and we await their reply.” The lead author of the study, Dr Mandeep Mehra, said he had contacted Surgisphere, the company that provided the data, to reconcile the discrepancies with “the utmost urgency”. Surgisphere is described as a healthcare data analytics and medical education company.

In a statement, Surgisphere founder Dr Sapan Desai, also an author on the Lancet paper, said a hospital from Asia had accidentally been included in the Australian data.

“We have reviewed our Surgisphere database and discovered that a new hospital that joined the registry on April 1, and self-designated as belonging to the Australasia continental designation,” the spokesman said. “In reviewing the data from each of the hospitals in the registry, we noted that this hospital had a nearly 100% composition of Asian race and a relatively high use of chloroquine compared to non-use in Australia. This hospital should have more appropriately been assigned to the Asian continental designation.”

He said the error did not change the overall study findings. It did mean that the Australian data in the paper would be revised to four hospitals and 63 deaths,.

Dr Allen Cheng, an epidemiologist and infectious disease doctor with Alfred Health in Melbourne, said the Australian hospitals involved in the study should be named. He said he had never heard of Surgisphere, and no one from his hospital, The Alfred, had provided Surgisphere with data.

“Usually to submit to a database like Surgisphere you need ethics approval, and someone from the hospital will be involved in that process to get it to a database,” he said. He said the dataset should be made public, or at least open to an independent statistical reviewer.

“If they got this wrong, what else could be wrong?” Cheng said. It was also a “red flag” to him that the paper listed only four authors.

“Usually with studies that report on findings from thousands of patients, you would see a large list of authors on the paper,” he said. “Multiple sources are needed to collect and analyse the data for large studies and you usually see that acknowledged in the list of authors.”

He stressed that even if the paper proved to be problematic, it did not mean hydroxychloroquine was safe or effective in treating Covid-19. No strong studies to date have shown the drug is effective. Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine have potentially severe and even deadly side effects if used inappropriately, including heart failure and toxicity. Other studies have found the drug is associated with higher mortality when given to severely unwell Covid-19 patients.

Australian doctors warned off after prescribing potentially deadly Covid-19 trial drug to themselves TOLD YA, HEADS UP THEIR ASSES

In a statement Surgisphere said it stood by the integrity of its data, saying all information from hospitals “is transferred in a deidentified manner” but could not be made public.

“This requirement allows us to only maintain collaborations with top-tier institutions that are supported by the level of data-integrity and sophistication required for such work,” the statement said. “Naturally, this leads to the inclusion of institutions that have a tertiary care level of practice and provide quality healthcare that is relatively homogenous around the world. As with most corporations, the access to individual hospital data is strictly governed. Our data use agreements do not allow us to make this data public.”

Scientists have reiterated the need to wait for the results from rigorous randomised control trials, considered the gold standard of science, and the Australian Department of Health has warned the drug should not be given to patients other than in clinical trials.

Cheng said it would be a mistake to stop strong, well-designed clinical trials examining the drug because of questionable data. The Lancet study findings have prompted the leaders of an Australian hydroxychloroquine trial, known as the Ascot trial, to review the future of their study. The outcome of that review has not yet been announced.

The Ascot study has been recruiting patients in more than 70 hospitals in every Australian state and territory, and 11 hospitals in New Zealand. The randomised control trial is exploring whether hydroxychloroquine in combination or on its own can treat Covid-19 patients and prevent deterioration in their condition. The leader of the trial, Prof Josh Davis, has written to the Lancet study authors asking for an explanation of the data.

In the meantime, patient recruitment for the study had been put on hold, an Ascot spokeswoman said. “Following an observational study published in the Lancet Ascot has paused patient recruitment pending deliberations by the governance and ethics committees overseeing the trial,” she said. “We expect these deliberations to occur rapidly and will provide further information as they arise.”

Questions about the paper’s statistical modelling have also come from other universities, including Columbia University in the US, prompting Surgisphere to issue a public statement.

Last month Australia’s chief scientist, Dr Alan Finkel, urged the public to be cautious about findings and interpretations from studies in the race to find cures and treatments for Covid-19.

Serious concerns have being raised by bioethicists, clinicians and scientists that scientific rigour and peer review is falling by the wayside in the race to understand how the virus spreads and why it has such a devastating impact on some people.

“This requirement allows us to only maintain collaborations with top-tier institutions that are supported by the level of data-integrity and sophistication required for such work,” the statement said. “Naturally, this leads to the inclusion of institutions that have a tertiary care level of practice and provide quality healthcare that is relatively homogenous around the world. As with most corporations, the access to individual hospital data is strictly governed. Our data use agreements do not allow us to make this data public.”

Scientists have reiterated the need to wait for the results from rigorous randomised control trials, considered the gold standard of science, and the Australian Department of Health has warned the drug should not be given to patients other than in clinical trials.

Cheng said it would be a mistake to stop strong, well-designed clinical trials examining the drug because of questionable data. The Lancet study findings have prompted the leaders of an Australian hydroxychloroquine trial, known as the Ascot trial, to review the future of their study. The outcome of that review has not yet been announced.

The Ascot study has been recruiting patients in more than 70 hospitals in every Australian state and territory, and 11 hospitals in New Zealand. The randomised control trial is exploring whether hydroxychloroquine in combination or on its own can treat Covid-19 patients and prevent deterioration in their condition. The leader of the trial, Prof Josh Davis, has written to the Lancet study authors asking for an explanation of the data.

In the meantime, patient recruitment for the study had been put on hold, an Ascot spokeswoman said. “Following an observational study published in the Lancet Ascot has paused patient recruitment pending deliberations by the governance and ethics committees overseeing the trial,” she said. “We expect these deliberations to occur rapidly and will provide further information as they arise.”

Questions about the paper’s statistical modelling have also come from other universities, including Columbia University in the US, prompting Surgisphere to issue a public statement.

Last month Australia’s chief scientist, Dr Alan Finkel, urged the public to be cautious about findings and interpretations from studies in the race to find cures and treatments for Covid-19.

Serious concerns have being raised by bioethicists, clinicians and scientists that scientific rigour and peer review is falling by the wayside in the race to understand how the virus spreads and why it has such a devastating impact on some people.

Deporting asylum seekers back to danger, Brownsville International Airport. Photo: Allan Mestel

Deporting asylum seekers back to danger, Brownsville International Airport. Photo: Allan Mestel

Matamoros encampment of asylum seekers. Photo: Allan Mestel.

Matamoros encampment of asylum seekers. Photo: Allan Mestel.

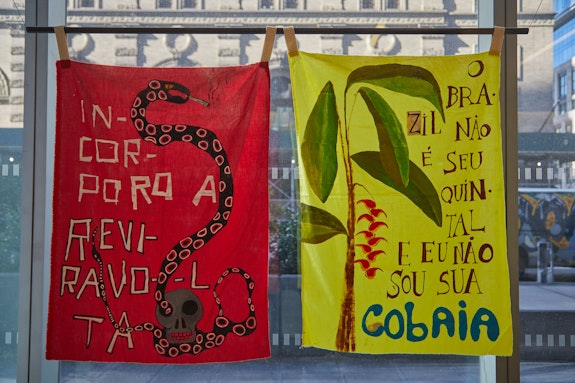

#CóleraAlegria, Selection of protest flags and slideshow with images of protests, 2016–ongoing. Dimensions variable. Courtesy the artists. Photo: Alex Korolkovas/Courtesy of AnnexB.

#CóleraAlegria, Selection of protest flags and slideshow with images of protests, 2016–ongoing. Dimensions variable. Courtesy the artists. Photo: Alex Korolkovas/Courtesy of AnnexB.