Parasitic fungi keep harmful blue-green algae in check

When a lake is covered with green scum during a warm summer, cyanobacteria—often called blue-green algae—are usually involved. Mass development of such cyanobacteria is bad for water quality because they can deprive the water of oxygen and produce toxins. But cyanobacteria can become sick, when for instance infected by fungal parasites. Researchers from the Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries (IGB) found out that these infections do not only kill cyanobacteria, they also make them easier to consume for their natural predators. Fungal parasites thus help to slow down the growth of blue-green algae.

Blue-green algal blooms are an increasing problem in waterbodies worldwide: Higher temperatures and growing nutrient loads lead to excessive growth of cyanobacteria. These mass developments affect water quality because many cyanobacteria produce toxins and reduce the oxygen concentration in the water, sometimes leading to death of fish and other aquatic organisms.

The international team led by IGB found that algal growth can be controlled by parasitic fungi. "Many of these algae have long filamentous shapes or grow in colonies, which makes them difficult to be eaten by their natural predators," explains Dr. Thijs Frenken, first author of the study and researcher at IGB and the University of Windsor in Canada. Chytrids, a very common group of fungi, often infect cyanobacteria. The researchers have now shown that, in addition to infecting and killing algae, the fungi "chop" the algae into shorter pieces, making them easier to be eaten by small aquatic organisms. "We knew that fungal infections reduce the growth of cyanobacteria, but now we know that they also make them easier prey," says IGB researcher Dr. Ramsy Agha, head of the study.

Fungi as food supplements for zooplankton

The researchers showed that in addition to "chopping" infected cyanobacteria filaments and making them more vulnerable to predation by small organisms in the water, zooplankton, parasitic fungi themselves serve as a valuable food supplement. Chytrid fungi contain various fats and oils that are an important part of the diet of small freshwater organisms and are not present in blue-green algae. Parasitic fungi therefore serve as an important dietary connection between different levels of aquatic food webs.

"These results show how parasites, although usually perceived as something bad, also have important positive effects on the functioning of aquatic ecosystems," says Professor Justyna Wolinska, head of the IGB research group Disease Evolutionary Ecology.

More information: Thijs Frenken et al. Infection of filamentous phytoplankton by fungal parasites enhances herbivory in pelagic food webs, Limnology and Oceanography (2020). DOI: 10.1002/lno.11474

Provided by Forschungsverbund Berlin e.V. (FVB)

]

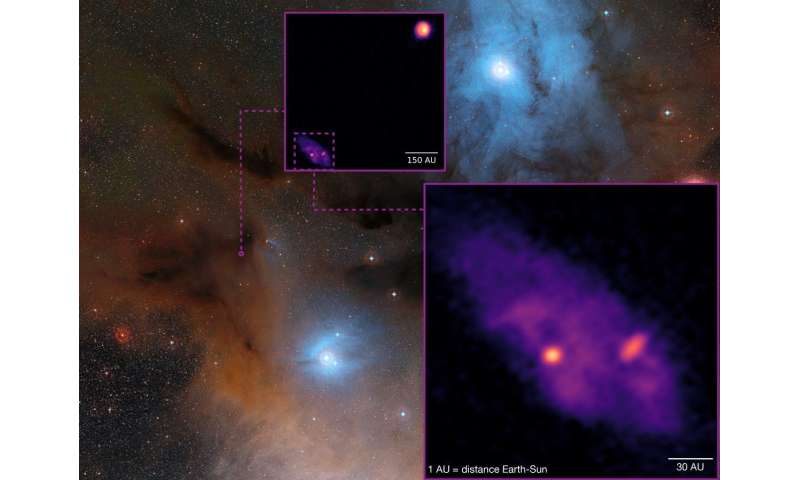

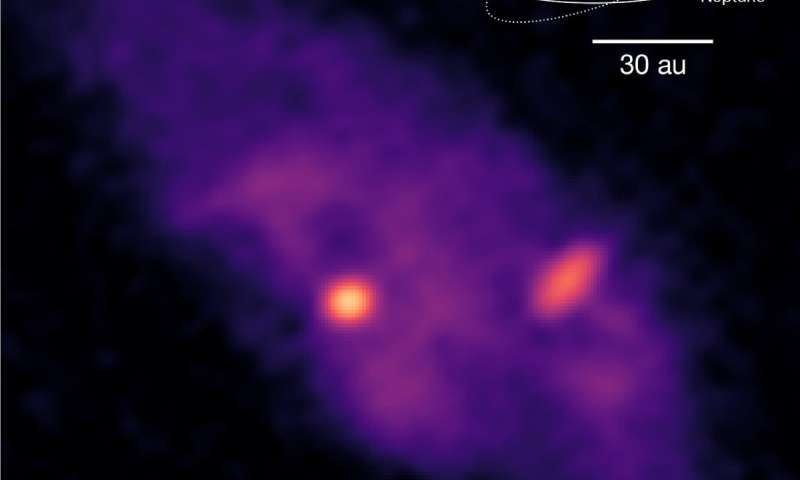

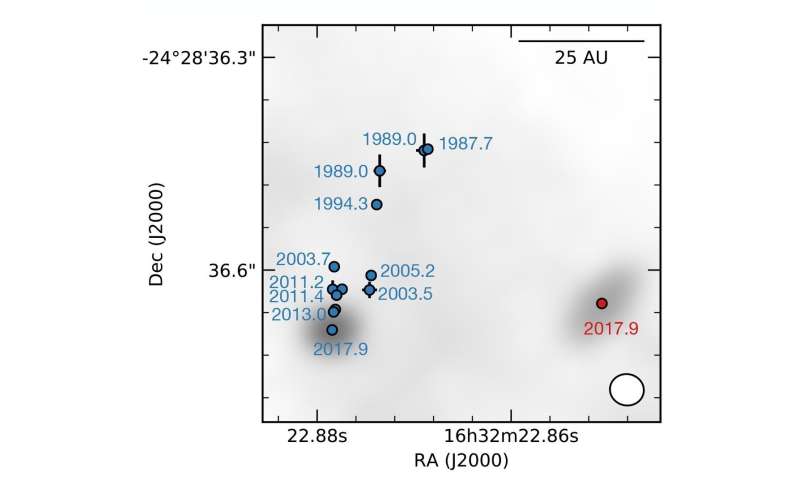

] Detailed view of the binary proto-star system with a size comparison to our solar system. The separation between the sources A1 and A2 is roughly the diameter of the Pluto orbit. The size of the disk around A1 (unresolved) is about the diameter of the asteroid belt. The size of the disk around A2 is about the diameter of the Saturn orbit. Credit: MPE

Detailed view of the binary proto-star system with a size comparison to our solar system. The separation between the sources A1 and A2 is roughly the diameter of the Pluto orbit. The size of the disk around A1 (unresolved) is about the diameter of the asteroid belt. The size of the disk around A2 is about the diameter of the Saturn orbit. Credit: MPE

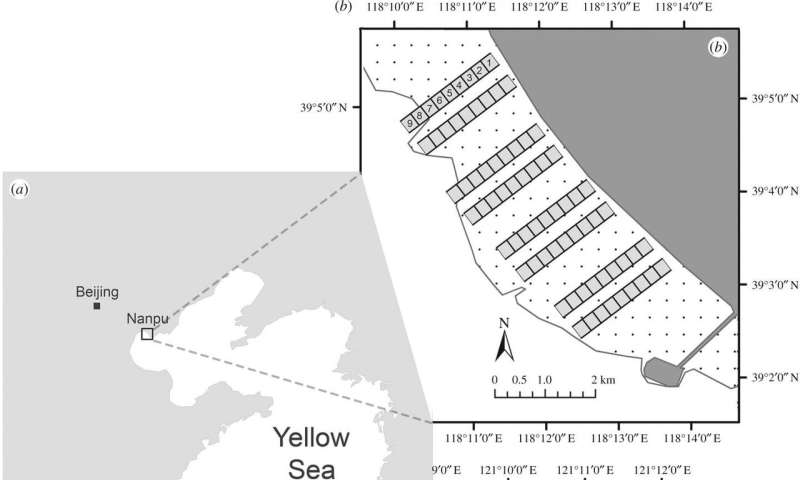

A key difference of the Princeton research was that it included observations of the high-tide period when the middle and lower tidal flats are underwater. The researchers focused on the East Asia-Australasian Flyway, which spans from Australia to Siberia along the rapidly developing coast of China where birds stop to rest and refuel. The researchers studied birds at two well-known stopover sites in the Yellow Sea region, Nanpu (b) near Beijing and Rudong (c) outside of Shanghai. The dark squares indicate the study plots along the upper, middle and lower tidal flats (dotted area). The white areas represent the sea beyond the low-tide line. Credit: Tong Mu, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

A key difference of the Princeton research was that it included observations of the high-tide period when the middle and lower tidal flats are underwater. The researchers focused on the East Asia-Australasian Flyway, which spans from Australia to Siberia along the rapidly developing coast of China where birds stop to rest and refuel. The researchers studied birds at two well-known stopover sites in the Yellow Sea region, Nanpu (b) near Beijing and Rudong (c) outside of Shanghai. The dark squares indicate the study plots along the upper, middle and lower tidal flats (dotted area). The white areas represent the sea beyond the low-tide line. Credit: Tong Mu, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology