What's the science on deep-sea mining for rare metals?

Some of the most sought-after metals and minerals on Earth lie deep — and largely untouched — in our oceans. Science and industry have been exploring those depths for decades. Here's an overview of what we know.

Relicanthus sp.— a new species from a new order of Cnidaria collected at 4,100 meters in the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone

Here's a simple fact to start: The oceans are huge. Oceans make up about 96.5% of all Earth's water. There's fresh water in the planet, in the ground or elsewhere on land in rivers and lakes — more than 70% of the planet is covered in water — and there's more all around us in the atmosphere. But the oceans are simply huge.

Our oceans remain some of the most under-researched parts of the planet. That's one reason why there's so much interest from both non-commercial scientists and those working in industry.

And when it comes to deep-sea research, there are two main areas of interest: conservation and mining.

Grown over millions of years: manganese nodules scattered on the deep seabed of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the Pacific

That's conservation of the many known and unknown species living at depths of up to about 5,500 meters in the Abyssal zone, which is predominantly in darkness.

That makes for some very unusual creatures that scientists would like to study out of pure interest. But because of this lack of knowledge it is also virtually impossible to know how species down there will react or survive once commercial mining begins.

That's mining for metals and minerals, such as nickel, cobalt, manganese and copper, which are found in polymetallic nodules on the same seabed that's home to those unknown creatures.

In fact, some deep-sea creatures live on those very nodules, which some people think are just waiting to be scooped up and turned into phones.

Why are we mining for these rare elements in the deep ocean?

We need (or want) them for a range of things, including the production of rechargeable batteries and touchscreens. And we're running low of these resources on land. That's also why there's an interest in mining asteroids — they hold important metals and minerals, too.

Sticking with the oceans, though, some estimates suggest there are greater deposits of manganese, cobalt and nickel on the deep-seabed than on land. Plus, there's more besides manganese nodules. There are polymetallic sulphides and cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts.

Since when has this been going on?

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) says it all began in 1873, and almost by chance, on an oceanography voyage conducted by a ship called HMS Challenger. The ISA says the ship's dredge hauled up "several peculiar black oval bodies which were composed of almost pure manganese oxide."

Those peculiar objects are now known as polymetallic or manganese nodules. They are often also referred to as potatoes — between 3 and 10 centimeters (1 and 4 inches) in diameter, and black.

It wasn't until the 1960s, however, when an American mining engineer, John L. Mero, brought manganese nodules to a "broader scientific readership" with his book "The Mineral Resources of the Sea."

A manganese nodule — the size of a large potatoes, but far more valuable to industry

That's according to Dr. Ole Sparenberg, a science historian at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology.

Sparenberg says Mero's book "drew the picture of an easy-to-harvest, vast, and virtually unlimited resource, which he even imagined as inexhaustible as the resource was allegedly growing faster than it could be exploited."

Mero may have been wrong about the latter notion, as more recent science suggests that areas that have been harvested for nodules show little sign of recovery even after 30 and 40 years. The nodules grow at a rate of millimeters per million years.

Sorry, what's the International Seabed Authority?

The ISA describes itself as "an autonomous international organization established under the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and the 1994 Agreement relating to the Implementation of Part XI of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea."

Basically, its role is divided between encouraging and supporting both industry and science, mining and conservation.

Where are we mining?

Well, commercial deep-sea mining has yet to really get off the ground. The ISA is still working on a mining code and other regulations, which some hope will be agreed at the body's next annual meeting (which has been postponed until October 2020).

A cobalt crust collected by German researchers from a seemount off the coast of West Africa

But the ISA has entered into a number of 15-year exploration contracts. At time of writing, the ISA says that includes 30 contractors, which are often companies sponsored by their national governments.

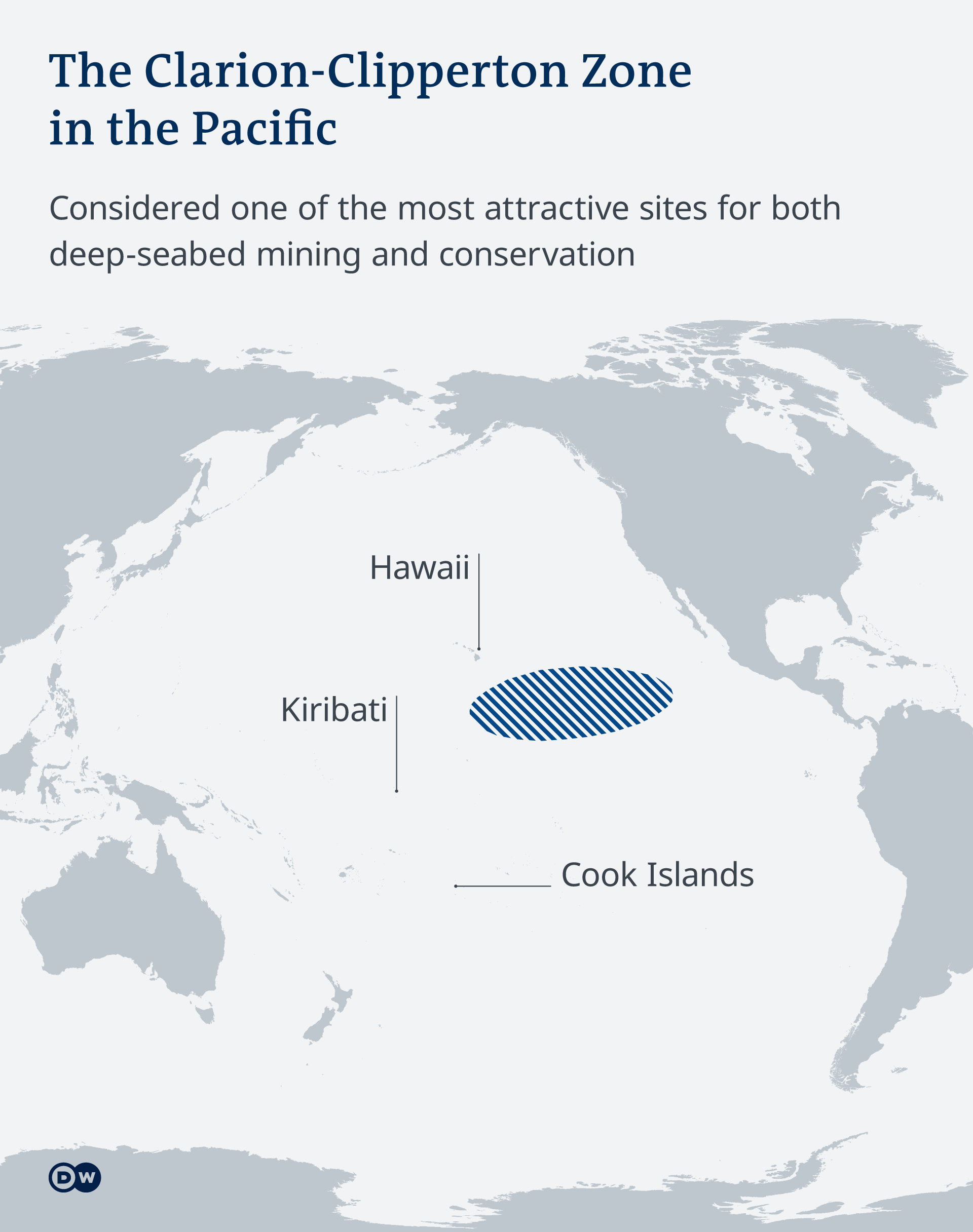

There are deposits all around the world. But a lot of the current interest is focused on the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone (CCZ) in the Pacific.

Eighteen of those contracts are for exploration for polymetallic nodules in the CCZ. Other contracts are for exploration in the Central Indian Ocean Basin and Western Pacific Ocean, and the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

Who are the main players?

Germany, for instance, has an exploration contract for polymetallic sulphides.

Polymetallic sulphides are a source of base metals, including copper, zinc, lead, and tin. They also include precious and special metals like gold, silver bismuth, selenium, tellurium, gallium or indium, which are used to make electronic components, like solar panels, and in telecommunication and other computer industries.

Other players include China, South Korea, Brazil, Russia, Japan — they have exploration contracts for cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts. Cobalt is a vital component in batteries, including car batteries. It is a rare mineral and considered dangerous to mine on land.

Deep-sea mining presents an advantage on that score as the ocean-based resources would be "harvested" by remotely-controlled machines that suck up the nodules or scrape crusts from underwater ridges.

One of many strange and wonderful deep-seabed creatures: Sea Cucumber Amperima sp. on the seabed in the eastern Clarion-Clipperton Zone

Poland, India, France, the UK, Belgian, Singapore, and, significantly, the Pacific islands of Kiribati, Cook Islands, Tonga, and Nauru have interests as well. It's significant because historically, it's been other countries, such as Australia, that have wanted to benefit from resources owned by the Pacific islander states.

Sounds great. What's the catch?

The problem is that the science seems to be lagging behind the more commercial interests in deep-seabed research. But it is catching up. And the concerns — while yet to be fully verified — have long existed.

A now nine-year-old study led by Dmitry M. Miljutin in France suggested that "about 1 square kilometers of sea floor will be mined daily, or about 6,000 square kilometers over the 20-year life of a mine site. […] Thus, the vast deep-sea seafloor will be seriously disturbed during the mining operations."

More recently, a study published this year by James Hein, Andrea Koschinsky and Thomas Kuhn suggests nodule collectors "will crush any organisms that are unable to escape and compact the sediment, reducing its habitability for sediment infauna."

Just waiting to be scooped up? Manganese nodules provide a habitat for many deep-seabed creatures

Additionally, the authors write that nodule mining could alter the geochemical composition of the sediment and water and cause "a short-term release of potentially toxic metals."

It's all "ifs and conditionals" at this point, but that's precisely why scientists want more time research the impact of deep-sea mining.

For instance, it's unclear how sediment will disperse when it's disturbed by a nodule harvester. The harvester may create so-called plumes — clouds — of sediment that could move unevenly across the seabed. Some creatures in the ocean's Abyssal zone live on the nodules and others, such as single-celled creatures called xenophyophores, use the sediment as covering, a safe habitat.

There are also concerns that ships above the harvesters will dump waste sediment and that that could suffocate plankton.

The ISA has designated Areas of Particular Environmental Interest (APEIs).

In the US, the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research says that the "APEIs were placed across the CCZ to protect and represent the full range of biodiversity and habitats in the region."

But the APEIs directly border those mining "claim areas." And some research suggests the sediment could resettle up to 10 kilometers away from a harvesting site, with unknown consequences.

One such area of concern is out in the Atlantic: the Lost City Hydrothermal Field.

Engineers are working on harvester technology that may reduce those plumes of sediment, but that's also a work in progress.

What we do know for certain is that areas where harvesting has been tested have so far shown little sign of recovery. There are two examples:

One test was conducted in 1989 — the DISCOL experiment led by Hjalmar Thiel, a scientist based in Hamburg. And the other was done by the Ocean Minerals Company out of the USA in the area of a French mining claim in the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone.

Decades later, the tracks of the dredgers could still clearly be seen.

- Date 05.06.2020

- Author Zulfikar Abbany

- Related Subjects Conservation, Oceans

- Keywords deep-sea mining, DSM, deep-seabed mining, fauna, batteries, metals, minerals, Clarion-Clipperton Zone, exploration, exploitation, conservation, oceans, World Oceans Day

- Permalink https://p.dw.com/p/3dGBx

Image: Protest Against Racism and Police Brutality In Berlin (Emmanuele Contini / NurPhoto via Getty Images file)

Image: Protest Against Racism and Police Brutality In Berlin (Emmanuele Contini / NurPhoto via Getty Images file)

Image: Black Lives Matter protest Germany (Maja Hitij / Getty Images)

Image: Black Lives Matter protest Germany (Maja Hitij / Getty Images)