Assange’s Eighth Day At Old Bailey: Software Redactions, Iraq Logs And Extradition Act – OpEd

September 18, 2020 Binoy Kampmark

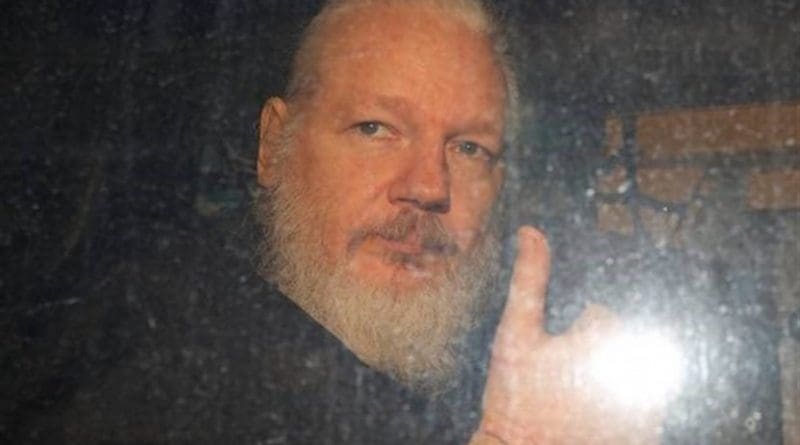

Julian Assange. Photo Credit: Tasnim News Agency

By Binoy Kampmark

The extradition trial of Julian Assange at the Old Bailey struck similar notes to the previous day’s proceedings: the documentary work and practise of WikiLeaks, the method of redactions, and the legacy of exposing war crimes. In the afternoon, the legal teams returned to well combed themes: testimony on the politicised nature of the Assange prosecution, and the dangers posed by the extra-territorial application of the Extradition Act of 1917 to publishing.

Assange the discerning publisher (for the defence) or reckless discloser (for the prosecution) were recurrent features. This time, it was John Sloboda, co-founder of the British NGO, Iraq Body Count, who took the stand. IBC had its origins in a noble sentiment: to give “dignity to the memory of those killed.” To know how loved ones perished sates a “fundamental human need”, and aids “processes of truth, justice, and reconciliation.” The outfit “maintains the world’s largest public database of violent civilian deaths since the 2003 invasion, as well as a separate running total which includes combatants.”

Central to Sloboda’s testimony was the importance of the Iraq War Logs, released in October 2010. As IBC puts it, the logs did not constitute the first release of US military data on Iraqi casualties but were pioneering, making it “possible to examine such data and to compare and combine it with other sources in a way that adds appreciably to public knowledge.” The compilation of 400,000 Significant Activity reports put together by the US Army comprised, in Sloboda’s words, “the single largest contribution to public knowledge about civilian casualties in Iraq.” They were, he told the court, “a very meticulous record of military patrols in streets in every area of Iraq, noting and documenting what they saw.” Some 15,000 previously unknown civilian deaths were duly identified.

In terms of collaboration, IBC approached WikiLeaks in the aftermath of publishing the Afghan War Diary. An invitation from Assange to join a media consortium including The Guardian, Der Spiegel and The New York Times followed. “It was impressed on us from our early encounters with Julian Assange that the aim was a very stringent redaction of documents to ensure that no information damaging to individuals was present.”

The redaction of the logs was part of a “painstaking process” that took “weeks”. Given the physical impossibility of manually redacting 400,000 documents in timely fashion, “The call was out to find a method that would be effective and would not take forever.” Sloboda made mention of a computer program developed by a colleague, one that would remove names from the documents. “It was a process of writing the software, testing it on logs, finding bugs, and running it again until the process was completed.”

The publication release was delayed, as the software in question “was not ready by the original planned publication date”. Modifications were also affected in terms of how thoroughly redaction might take place of “different categories of information”: the removal of architectural features (mosques, for instance), or expertise or professions of individuals.

Pressure was placed on WikiLeaks by the other media partners to publish. Their contribution to the redaction process had been sparse and manual: a mere sampling. Assange held firm against such impatience: redactions had to take place systematically; “the entire database,” recalled Sloboda, was “to be released together.” If anything, the final product was one of overcautious sifting, one overly pruned to prevent any dangers.

For all that, Sloboda insisted in his witness statement that a decade on, the Iraq War Logs “remain the only source of information regarding many thousands of violent civilian deaths in Iraq between 2004 and 2009.” The position of IBC was simple: “civilian casualty data should always be made public.” In doing so, no harm hard occurred to a single individual, despite repeated assertions by the US government to the contrary, not least because of the thorough redaction process. “It could well be argued, therefore, that by making this information public, [Chelsea] Manning and Assange were carrying out a duty on behalf of the victims and the public at large that the US government was failing to carry out.”

Joel Smith QC for the prosecution duly probed Sloboda on his experience in the field of classifying or declassifying documents, and whether he had earned his stripes dealing with corroborating sources in an oppressive regime. Such questioning had a simple purpose: to anathemise the civilian or journalist publisher of documents best left to agents and thumbing bureaucrats. Had Sloboda and staff at the IBC been appropriately vetted? “We paid a visit to the offices of the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and were asked to sign a non-disclosure agreement with the then director Iain Overton. I don’t remember any vetting process.”

Sloboda, in his written submission, conceded that the previous publications by WikiLeaks, in particular the Afghan War Diary, came with its host of challenges, a “steep learning curve for all of those concerned.” To Smith’s questioning, he revealed that “there was a sense there needed to be a better process in the next round”, the redaction process having not quite been up to scratch.

Another line of the prosecution’s inquiry was the accuracy of the redaction. Was there human agency at any time in reviewing the war logs to avoid any “jigsaw risk” enabling the identification of individuals? Checking did take place, answered Sloboda, “but no human could go through them all.”

Smith, as with other prosecutors, persevered with the Assange as ruthless motif, this time asking if Sloboda was aware of comments allegedly made at the Frontline Club for journalists. The transcript of the event supposedly has the publisher claiming that WikiLeaks nursed no obligation to protect sources in leaked documents except in cases of unjust reprisal. “Today is the first time that I have read the transcript.” Sloboda could “remember nothing like that in our conversations about the Iraq logs.”

The possibility that Iraqi lives were probably put at risk was aired, with Smith reading a witness statement from assistant US attorney Kellen S. Dwyer that the Iraq War Logs had named local Iraqis who had been informants for the US military. (Dwyer’s competence might be gauged by the “cut and paste” mistake he made in revealing that Assange had been charged under seal.) To this unprovable assertion or assessment (qualifying risk and harm), Sloboda expressed surprise; if the reference was to “the heavily redacted logs published in October 2010, this is the first time I have heard of it.”

Human rights attorney and historian Carey Shenkman followed to testify via videolink. Shenkman, a keen student of the historical and often invidious use of the Espionage Act, was in the employ of the late and formidable Michael Ratner, president emeritus of the Center for Constitutional Rights. Shenkman’s written testimony is withering of the statute now being used with such relish against Assange.

Much said by Shenkman would be familiar to those even mildly acquainted with that period of executive overreach. It arose from “one of the most politically repressive” times in US history, a nasty product of the Woodrow Wilson administration’s fondness of targeting dissidents. “During World War I, federal prosecutors considered the mere circulation of anti-war materials a violation of the law. Nearly 2,500 individuals were prosecuted under the Act on account of their dissenting opposition to US entry into the war.” Among them were such notables as William “Big Bill” Haywood of the International Workers of the World, film producer Robert Goldstein and, with much disgrace, Eugene Debs, presidential candidate for the Socialist Party.

The word “espionage”, he explained to Judge Vanessa Baraitser, was a misnomer. “Although the law allowed for the prosecution of spies, the conduct it prescribed went well beyond spying.” The Act became the primary “tool for what President Wilson dubbed his administration’s ‘firm hand of stern repression’ against opposition to US participation in the war.”

As Shenkman noted in his statement to the court, the Act targeted spying for foreign enemies in wartime and was intended to address “such matters as US control of arm shipments and its ports”. But it also “reflected the government’s desire to control information and public opinion regarding the war effort.”

Its broadness lies in how it criminalises information: not merely “national security information” but all material falling under the umbrella of “national defence” information. Shenkman has previously argued that public interest defences focused on the positive outcomes of disclosures be given to whistleblowers and hacktivists. But for the First Amendment advocate, the Espionage Act remains fiendishly controversial when it comes to the press, the reason, he testified, why there was never “an indictment of a US publisher under the law for the publication of secrets. Accordingly, there has never been an extraterritorial indictment of a non-US publisher under the Act.”

The idea of prosecuting publishers involving grand juries had been flirted with in some cases, but never seen through. Shenkman offered a few highlights. The Chicago Tribune faced the possibility in 1942 when it published secrets after the Battle of Midway. The effort crumbled when the prosecutor in that case, William Mitchell, expressed doubts that the Espionage Act extended to newspapers. The Truman administration had also tentatively tested these waters, arresting three journalists and three government sources for conspiracy to violate the Act. No indictments followed, though it emerged that political pressure had been brought to bear on the Justice Department from “multiple factions within the Truman administration.” An uproar led to a jettisoning of the case and the imposition of small fines.

Previous examples are also noted in Shenkman’s court submission, including the threatened prosecutions of Seymour Hersh during the Ford administration, and James Bamford in 1981. Dick Cheney, future dark puppeteer of the George W. Bush administration, felt it would be “a public relations disaster” to target Hersh.

According to Shenkman, a chilling change in the winds took place during the Obama administration, if only briefly. Fox News journalist James Rosen had been named as an “aider, abettor, and co-conspirator” in a Justice Department case against Stephen Kim, a State Department employee. The effort stalled and Eric Holder’s remarks on resigning as Attorney General in 2014 spoke of deep regret that Rosen had ever been named. Journalists felt relief.

Then came the Assange indictment. “I never thought based on history we’d see an indictment that looked like this.” It was part of the Trump administration’s desire “to escalate prosecutions as well as ‘jailing journalists who publish classified information.’ The Espionage Act’s breath provides such a means.”

Prosecutor Claire Dobbin was blunter than her colleague, preoccupied with attacking Shenkman’s credibility for having worked with Ratner when representing Assange. Little time was spent on the substance of Shenkman’s submission; instead, the prosecution sought to convince the witness that the case against Assange would be best heard on US soil.

What mattered to Dobbin was taking the politics out of the prosecution. Surely, she put to Shenkman, he could still believe in 2015 that the US would bring charges against Assange. The less than subtle insinuation here is that a refusal to do so under the Obama administration was merely a lull rather than an abandonment of interest. “[O]ftentimes,” replied Shenkman, “these things are left to simmer, but ultimately, an indictment was not brought.” Had President Barack Obama and Attorney General Holder wished to pursue Assange, they would have surely shown a measure of eagerness to do so.

More could be said about the politicisation thesis: the singular use of the Espionage Act, the framing of the charges, and the timing of the indictment, all pointing to “a highly politicized prosecution.”

Prosecutorial tactics switched to hair splitting. What constituted the stealing of national security and national defence information? Would that be covered by the First Amendment? Depends, countered Shenkman, reminding Dobbin of the recent 9th Circuit Court of Appeals decision in United States v Moalin accepting the merit of Edward Snowden’s disclosures on unwarranted surveillance by the National Security Agency, despite deriving from an instance of theft.

There was a divergence of views on the issue of “hacking” as well. “Are you saying that hacking government databases is protected under the First Amendment?” shot Dobbin. Again, more clarity was needed, suggested Shenkman. The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, for instance, makes no reference to the term. Nuance is required: “crack a password’ and “hack a computer” have “scary” connotations; in other instances there would be “ways the First Amendment could be relevant.”

Given such disagreement and lack of clarity of terms, Dobbin pushed Shenkman to agree that a US court would be the most appropriate body to determine the issue. “No,” came the emphatic answer. The way the indictment had been drafted was political. The prosecution had, effectively, dithered.

Home » Assange’s Eighth Day At Old Bailey: Software Redactions, Iraq Logs And Extradition Act – OpEd

Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge.