Airport shut as city governor condemns ‘anarchy’ and violence surrounding Sars police brutality protests

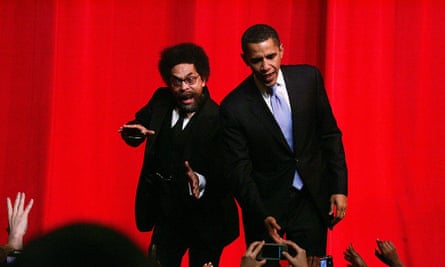

People in Lagos demonstrating against police brutality in Nigeria.

Photograph: Sunday Alamba/AP

Emmanuel Akinwotu in Lagos

Tue 20 Oct 2020

The government of Lagos has imposed an immediate 24-hour curfew, shutting down protests against police brutality that have erupted across Nigeria and paralysed large areas of the state that includes Africa’s largest city.

The protests have been against the notorious Sars police unit, now dissolved but accused of scores of extra-judicial killings. More broadly the protests have been against systemic abuse by Nigerian police forces. Early in the protests, police fired on protesters in the Surulere area of Lagos and elsewhere. Armed gangs have attacked protesters in Lagos and the capital Abuja.

The demonstrations had “degenerated into a monster threatening the well-being of our society”, said Babajide Sanwo-Olu, the governor of Lagos, in a statement on Tuesday.

His statement came after a police station was set on fire in the Iganmu area of Lagos on Tuesday morning. The national police chief also ordered the immediate deployment of anti-riot forces following increased attacks on police facilities, a police spokesman said.

Nigeria's anti-police brutality protests bring Lagos to standstill

“Criminals and miscreants are now hiding under the umbrella of these protests to unleash mayhem on our state,” he said, promising that the government would “not watch and allow anarchy”.

In recent days violence on the streets has fuelled unrest across Nigerian cities, amid one of the most striking protest movements in a generation against police brutality.

Four Nigerian states, and the capital, Abuja, have banned protests or adopted curfews effectively banning demonstrations.

Several protesters yesterday targeted Lagos airport, blocking off entrances to its international and domestic terminals, causing flight delays.

Emmanuel Akinwotu in Lagos

Tue 20 Oct 2020

The government of Lagos has imposed an immediate 24-hour curfew, shutting down protests against police brutality that have erupted across Nigeria and paralysed large areas of the state that includes Africa’s largest city.

The protests have been against the notorious Sars police unit, now dissolved but accused of scores of extra-judicial killings. More broadly the protests have been against systemic abuse by Nigerian police forces. Early in the protests, police fired on protesters in the Surulere area of Lagos and elsewhere. Armed gangs have attacked protesters in Lagos and the capital Abuja.

The demonstrations had “degenerated into a monster threatening the well-being of our society”, said Babajide Sanwo-Olu, the governor of Lagos, in a statement on Tuesday.

His statement came after a police station was set on fire in the Iganmu area of Lagos on Tuesday morning. The national police chief also ordered the immediate deployment of anti-riot forces following increased attacks on police facilities, a police spokesman said.

Nigeria's anti-police brutality protests bring Lagos to standstill

“Criminals and miscreants are now hiding under the umbrella of these protests to unleash mayhem on our state,” he said, promising that the government would “not watch and allow anarchy”.

In recent days violence on the streets has fuelled unrest across Nigerian cities, amid one of the most striking protest movements in a generation against police brutality.

Four Nigerian states, and the capital, Abuja, have banned protests or adopted curfews effectively banning demonstrations.

Several protesters yesterday targeted Lagos airport, blocking off entrances to its international and domestic terminals, causing flight delays.

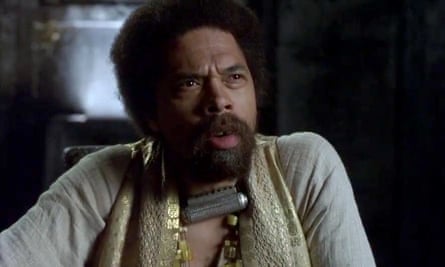

A one-minute silence on Monday among the crowds near Murtala Muhammed airport, Lagos, to remember ‘lives lost to police brutality’.

Photograph: Benson Ibeabuchi/AFP/Getty

Outrage against the federal Special Anti-Robbery Squad, commonly called Sars, reached a tipping point after footage posted online early October showed Sars officers dragging a man from a hotel in Lagos before shooting him in the street.

Thousands of mainly young people have taken to the streets, many for the first time, demanding immediate police reforms. Protests led by young people have raised more than £200,000, setting up helplines for protesters in trouble, covering medical aid and providing private security.

In response to widespread demonstrations, which are not common in Nigeria, the government has dissolved the unit and adopted numerous measures, including judicial panels to investigate Sars abuses and compensation for victims.

Yet protests have grown, amid criticism that the pledges do not go far enough, following several previous pledges to reform or overhaul the unit.

Many people are incensed that Sars officers have not been arrested despite a deluge of video evidence showing abuses, including, in recent weeks, at demonstrations. The government said though that in Lagos four officers were arrested for violence against protesters and were under trial.

The announcement of the new police unit, the Special Weapons and Tactics (Swat) team, to partly replace Sars, has caused anger too.

In recent days, people wielding machetes, knives and clubs have attacked protesters, leaving many injured according to Amnesty International.

At least 15 people have died since protests began two weeks ago, Amnesty said. The organisation condemned widespread violence by police forces against peaceful demonstrations.

Amnesty International Nigeria said yesterday: “In the past few days we have documented escalating violence and coordinated attacks against peaceful #EndSars protesters.” It said police had used “excessive force” leading to many casualties.

Footage posted online showed dozens of young men with machetes, knives and sticks arriving at the scene of a protest sit-in outside the Lagos state government secretariat last Thursday, then attacking fleeing protesters.

Witnesses accused security forces of standing idly by. Lagos’ government condemned the violence and ordered an investigation.

In Benin City, in the southern state of Edo, people broke into a prison on Monday morning. Footage on social media showed several prisoners fleeing and climbing out of the prison, joining groups of men in the city vandalising property.

Edo’s governor, Godwin Obaseki, ordered a 24-hour curfew, blaming vandalism “by hoodlums in the guise of #EndSARS protesters”.

In Obalende, a busy market area in Lagos, people put up road blocks with tyres and rocks and extorted cash from drivers, as protests took place nearby, mirroring similar reports across the city.

The unrest has grown, alongside warnings from the army that soldiers would be ready to intervene, and calls from government officials pleading with protesters to end the demonstrations.

Outrage against the federal Special Anti-Robbery Squad, commonly called Sars, reached a tipping point after footage posted online early October showed Sars officers dragging a man from a hotel in Lagos before shooting him in the street.

Thousands of mainly young people have taken to the streets, many for the first time, demanding immediate police reforms. Protests led by young people have raised more than £200,000, setting up helplines for protesters in trouble, covering medical aid and providing private security.

In response to widespread demonstrations, which are not common in Nigeria, the government has dissolved the unit and adopted numerous measures, including judicial panels to investigate Sars abuses and compensation for victims.

Yet protests have grown, amid criticism that the pledges do not go far enough, following several previous pledges to reform or overhaul the unit.

Many people are incensed that Sars officers have not been arrested despite a deluge of video evidence showing abuses, including, in recent weeks, at demonstrations. The government said though that in Lagos four officers were arrested for violence against protesters and were under trial.

The announcement of the new police unit, the Special Weapons and Tactics (Swat) team, to partly replace Sars, has caused anger too.

In recent days, people wielding machetes, knives and clubs have attacked protesters, leaving many injured according to Amnesty International.

At least 15 people have died since protests began two weeks ago, Amnesty said. The organisation condemned widespread violence by police forces against peaceful demonstrations.

Amnesty International Nigeria said yesterday: “In the past few days we have documented escalating violence and coordinated attacks against peaceful #EndSars protesters.” It said police had used “excessive force” leading to many casualties.

Footage posted online showed dozens of young men with machetes, knives and sticks arriving at the scene of a protest sit-in outside the Lagos state government secretariat last Thursday, then attacking fleeing protesters.

Witnesses accused security forces of standing idly by. Lagos’ government condemned the violence and ordered an investigation.

In Benin City, in the southern state of Edo, people broke into a prison on Monday morning. Footage on social media showed several prisoners fleeing and climbing out of the prison, joining groups of men in the city vandalising property.

Edo’s governor, Godwin Obaseki, ordered a 24-hour curfew, blaming vandalism “by hoodlums in the guise of #EndSARS protesters”.

In Obalende, a busy market area in Lagos, people put up road blocks with tyres and rocks and extorted cash from drivers, as protests took place nearby, mirroring similar reports across the city.

The unrest has grown, alongside warnings from the army that soldiers would be ready to intervene, and calls from government officials pleading with protesters to end the demonstrations.