Coconut oil threatens more species than palm oil

New research finds that coconut production threatens a lot more endangered species than initially thought.

(Photo: Perfect Lazybones / Shutterstock / NTB scanpix)

Coconut oil is often hailed as an environmentally friendly alternative to, for example, palm oil, but new research shows that it actually threatens more species than the controversial palm oil. How to choose environmentally friendly vegetable oils in a world full of disinformation?

Cathrine Glosli COMMUNICATION ADVISOR

NMBU, Norwegian University of Life Sciences

Monday 06. july 2020 -

Coconut oil is used in a wide variety of products, both in food and cosmetics. The oil is hailed by many as both healthy and environmentally friendly, and it is often mentioned as an alternative to palm oil.

However, new research shows that coconut oil is nowhere near as environmentally friendly as widely assumed, and that it actually threatens more animal and plant species than other vegetable oils.

"Our research shows that coconut production threatens a lot more endangered species than initially thought, and consequently there is a lot of confusion about the production of vegetable oils and which ones that actually can be considered environmentally friendly," says Professor Douglas Sheil from the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU).

He is one of several researchers behind a new international study that deals with the production of vegetable oils and the effects these crops have on nature and the environment.

Affects many species

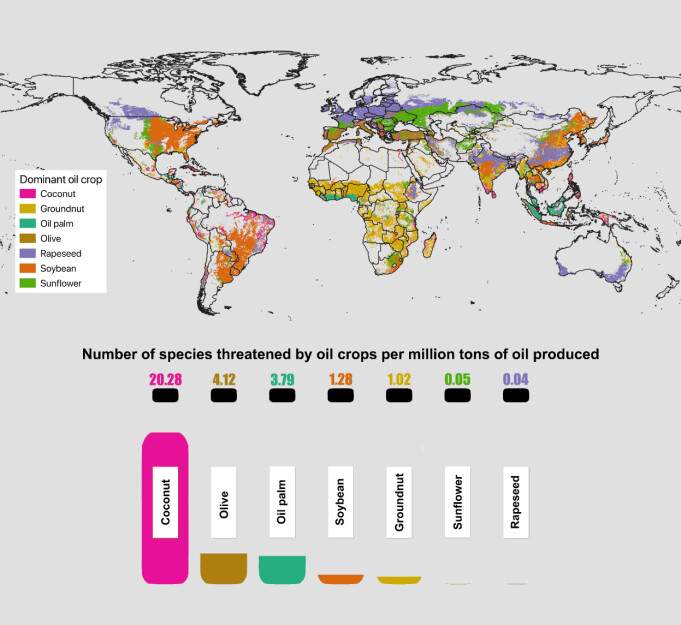

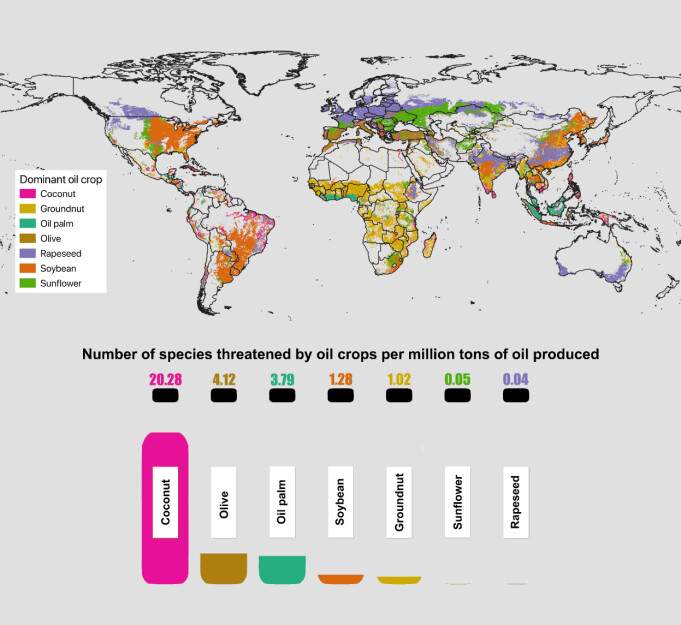

According to the study, coconut oil production affects 20 endangered species per million litre produced oil. This is higher than other vegetable oils, such as palm oil (3.8 species per million litres), olives (4.1) and soybean (1.3).

Why is the coconut so bad for biodiversity? The main reason is that it is mostly cultivated on tropical islands with a rich diversity of species and many native species found nowhere else.

The effect on endangered species is usually measured by the number of species affected per area of land used - and according to this calculation, palm oil is worse than coconut.

Global map showing the dominant oil crop per grid-cell. Oil levels in the bottles represents the number of species threatened by each oil crop per million tons of oil produced.

Threatening endangered species

The researchers have gone through all the species in the IUCN Red List, the official red list of the world's endangered species. From the long inventory of 100,000 endangered species, they have filtered out all who are considered endangered by the cultivation of palm oil, maize, coconut, peanuts, olives, rapeseed, soy and/or cotton.

They have then linked this information with crop-specific data on how many hectares are harvested by the different crop types per land area globally.

Based on this, they could put a value on the number of endangered species per million tonnes of oil produced.

Here the coconut production came out worse than expected, and considerably worse than what is widely believed.

Food production: the backside of the story

Few, if any, human activities have changed the world more than agriculture. An ever-increasing human population growth and need for food, feed and biofuels has meant that arable land and grazing land now cover over 40% of the globe's total land area. Which consequently has large effects on the climate and biological diversity.

Coconut cultivation is thought to have contributed to the extinction of a number of island species, including the Marianne white-eye in the Seychelles and the Solomon Islands’ Ontong Java flying fox.

The Sangihe Tarsier is one of the species that is threatened by deforestation and clearing of ground vegetation for coconut production. (Photo: Stenly Pontolawokang)

Species not yet extinct but threatened by coconut production include the Balabac mouse-deer, which lives on three Philippine islands, and the Sangihe tarsier, a primate living on the Indonesian island of Sangihe.

"The most important take away from the study is not that coconut oil is so much worse than other vegetable oils", says Professor Douglas Sheil. Rather, consumers need to realize that all agricultural commodities have negative environmental impacts. (Photo: Private)

Define “eco-friendly”

In recent years, there has been an increasing trend that environmentally conscious consumers are actively looking for and favouring "environmentally friendly" products.

“The challenge is that the information about what constitutes eco-friendly is picked from unreliable sources,” says Sheil.

Producers, merchants, dealers, governments and interest groups - all are vying to tell the consumers what they should spend their money on.

“The result of this is that the information is often both contradictory and confusing,” he comments.

All crops have consequences

"The most important thing about this study is not that coconut oil is so much worse than other types of vegetable oils,” Sheil explains.

The researchers note that olives and other crops also raise concerns.

“However, it is that we as a society need to improve the information stream to the consumer," he continues.

“Consumers must realize that all our agricultural commodities, and not just those from tropical areas, have negative environmental impacts.”

“There is a need for increased transparency and better information. We must make it easier to act in an environmentally friendly manner, but the information must also be credible.”

Reference:

Meijaard et al. 2020. Coconut oil, conservation and the conscientious consumer. Current Biology.

DOI & URL: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.05.059

https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(20)30746-6

THIS ARTICLE IS PRODUCED AND FINANCED BY THE NORWEGIAN UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES (NMBU) - READ MORE