Turkey's shining liver transplant industry has humble origins

MURAT SOFUOGLU

Yaman Tokat, a leading Turkish surgeon, speaks to TRT World and explains what made Turkey a global leader in the liver transplant industry.

Like a Sufi dervish following his master, Turkish surgeon Yaman Tokat followed Mehmet Muhlis Tekdogan, a well-known heart surgeon in Turkey.

The year was 1987 and Tekdogan had returned to Turkey after spending several years in the US, where he had earned fame as a professor at the University of Chicago. He returned to his homeland with a mission to develop a heart surgery department in the Ege University and slowly build an organ transplant discipline in the country's healthcare sector.

As Tekdogan met then-28-year-old Tokat, a native of Izmir’s Karsiyaka district, he saw in him a man who would fight all the odds and carry out ambitious surgical tasks assigned to him.

“One day the teacher (hoca in Turkish) called me. I was one of his first assistants. ‘My child, do a kidney transplant this week,’ he told me,” Tokat recalls.

It was a time when such transplant operations were neither performed at the Ege University nor in Izmir. Although such surgeries were performed in some other parts of Turkey, the results were mixed: some became successful, some resulted in failures.

“In Turkey, at the time, there was no such concrete medical concept like kidney transplant from a cadaver,” Tokat says.

In light of all the complexities and lack of resources, what Tekdogan demanded from Tokat was not an ordinary operation at all. Instead, it was a very fearful task for surgeons, which turned their dreams into nightmares.

“But in Turkish surgery, if you loudly question an instruction and say 'how the hell can I do this?', then, they [master surgeons] would not assign that task to you ever. If they offer you an assignment, you should just say under any conditions ‘Yes, I can do it’,” Tokat tells TRT World.

“You should not say ‘I don’t know’ or ‘I cannot do it’. That’s what I have learned [from my teachers],” Tokat said, his expressions underlining as if he was sharing the secrets of his surgical success in Turkey.

Turkish model

As Turkey lacked organisational structure in sectors like liver or kidney transplant, individual actions came first before a stable system supporting those crucial surgical procedures came into being, Tokat says. But in the developed world, where a stable system has already been in place, an intervention like Tekdogan's is not needed as their systems naturally decide the order of individual actions, he adds.

“In our case, someone, who knows the job, shows how it should be done, then, things begin to move towards establishing a system,” he explains. In Tokat’s case, it was Tekdogan who "led the charge."

“He came from the US to start this at the Ege University and led the charge. His ‘You-guys-will-do-this' determination made things move there. We could not achieve anything without his leadership and connections,” Tokat says.

While gaining speciality in general surgery for five years, he worked intensely on kidney transplantation. Tokat and his friends also opened Turkey’s first coordination centre in Izmir to organise people to donate their organs.

When Tokat completed his specialisation course, Tekdogan called him again.

“This time he told me ‘Ok, let’s do a liver transplant,’” he said, adding that he immediately followed the advice and researched on which institution was the best for liver transplant.

As he found Britain’s Cambridge University, he moved there in 1993 to deepen his knowledge and practice of liver transplant.

“I learned how to do a liver transplant there with its full procedure. In 1994, when I came back to Turkey, I started doing liver transplant operations. The first time in the country’s history, my team was able to conduct successful operations with patients living for longer periods afterwards,” Tokat says, referring to the surgeries he performed in the Ege University.

Before Tokat conducted liver transplants, Turkey had recorded a few surgeries in the field. In 1988, the first liver transplantation was performed by Mehmet Haberal, whose team also did the first deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT) in 1990.

But no patients could live for longer periods afterwards, Tokat says, referring to previous operations. “I did the first successful liver transplant in Turkey with the patient living ten years after the operation on August 24, 1994,” says Tokat.

Fatma Akin was Yaman Tokat’s first liver transplant patient, who was also Turkey’s first long term transplant survivor. She became pregnant three months after the operation in 1994. She had a healthy boy named after Tokat’s first name, Yaman. The picture was taken in 2004. (Credit: Yaman Tokat / TRTWorld)

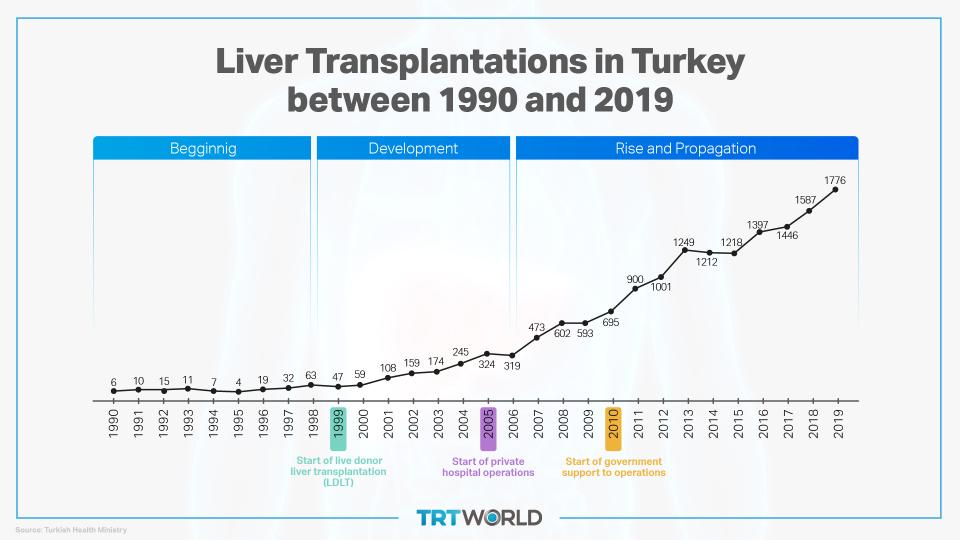

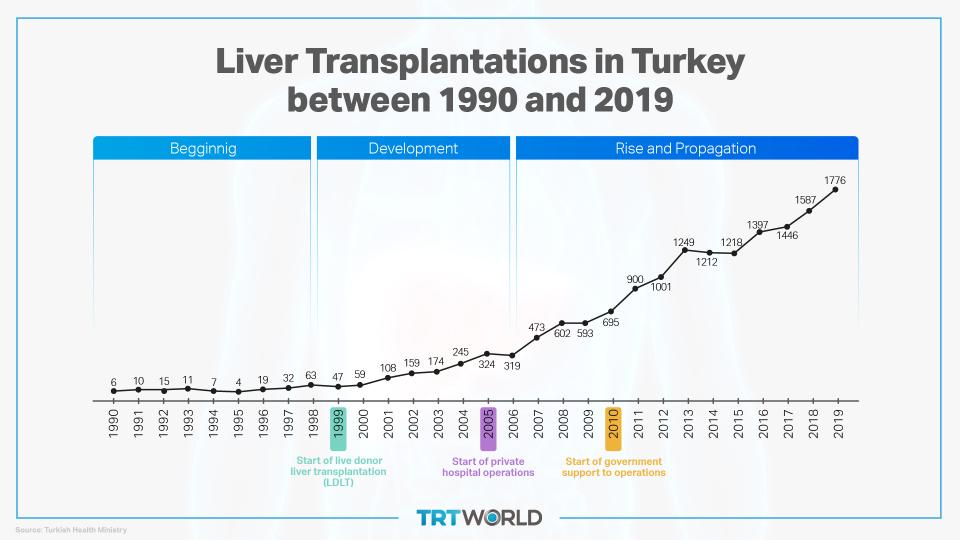

Under Tokat’s leadership, Turkey’s first successful DDLT program was established in 1994 in Izmir. Five years later, he also established the first live donor liver transplantation (LDLT) program in the Ege University.

Leading the charge

From 1994 to 1997, Tokat’s team had conducted ten back-to-back liver transplants — each one showed amazingly successful results. The subsequent surgical feats shot him to fame in Turkey. In October 1997, one of Turkey’s private television channels even broadcasted one of his liver transplant operations live on TV.

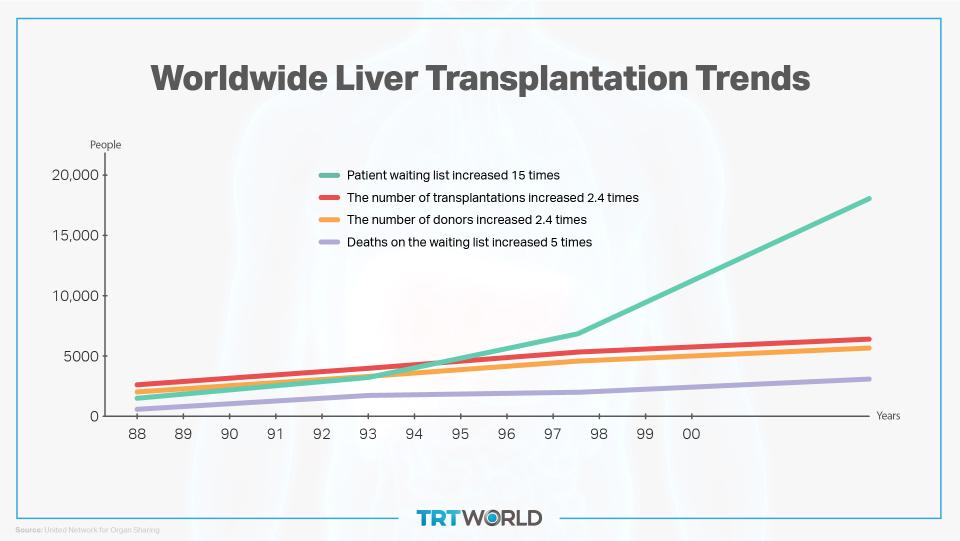

“When people saw that a liver transplant is indeed possible and a patient could live after an operation, there was a real increase in the number of people donating their organs, making 1997 a turning point for the development of the country’s liver transplant sector,” Tokat says.

In 1998, a new development emerged across the world, which was the possibility of live donor liver transplantation (LDLT). Then, Tokat went to Japan’s Kyoto, which was known as the hub of LDLT, to learn this new technique. He stayed there for 15 days, joining a couple of operations. He came back with VHS footage of the operations.

“At the time, there was no Youtube or anything like that,” he says.

“When I was back in Izmir, I and one of my partners sat down on a weekend on one of the hottest days of the year, watching those 5-minute videos maybe forty times to memorise every move”.

Under Tokat’s leadership, Turkey’s first successful DDLT program was established in 1994 in Izmir. Five years later, he also established the first live donor liver transplantation (LDLT) program in the Ege University.

Leading the charge

From 1994 to 1997, Tokat’s team had conducted ten back-to-back liver transplants — each one showed amazingly successful results. The subsequent surgical feats shot him to fame in Turkey. In October 1997, one of Turkey’s private television channels even broadcasted one of his liver transplant operations live on TV.

“When people saw that a liver transplant is indeed possible and a patient could live after an operation, there was a real increase in the number of people donating their organs, making 1997 a turning point for the development of the country’s liver transplant sector,” Tokat says.

In 1998, a new development emerged across the world, which was the possibility of live donor liver transplantation (LDLT). Then, Tokat went to Japan’s Kyoto, which was known as the hub of LDLT, to learn this new technique. He stayed there for 15 days, joining a couple of operations. He came back with VHS footage of the operations.

“At the time, there was no Youtube or anything like that,” he says.

“When I was back in Izmir, I and one of my partners sat down on a weekend on one of the hottest days of the year, watching those 5-minute videos maybe forty times to memorise every move”.

(Musab Abdullah Gungor / TRTWorld)

The following year, in 1999, his team conducted Turkey’s first successful LDLT operation, taking the country to the new age of both organ donation and the LDLT. Both the techniques became popular in Turkey for reasons ranging from religious considerations to close family relations.

“We began doing like 100 operations per year,” Tokat says, referring to a period between 1999 and 2005, when he decided to move the whole liver transplant program to Istanbul’s Florence Nightingale Hospital. For 15 years, his team had worked there until he decided to establish a new center, International Liver Center, this year. He now performs all the liver transplantation operations in his new center.

More than three decades after he conducted the first kidney transplant operation in Izmir, Tokat is now considered to be one of Turkey’s leading liver transplant surgeons, who is also well-known across the world and has earned the reputation of being a fearless surgeon. Since 1994, he has done more than 1,500 liver transplants. He once performed 143 surgeries a year, he recalls.

Turkey: a rising star

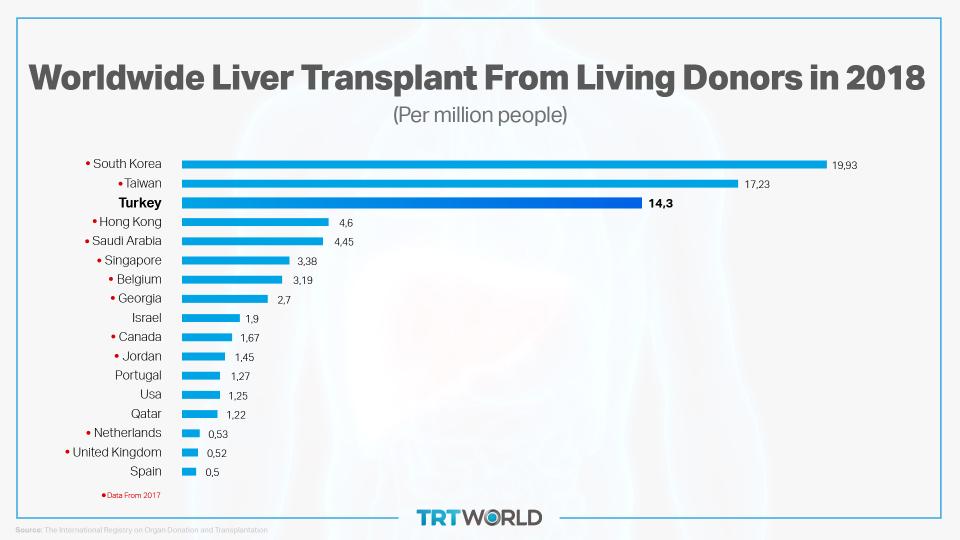

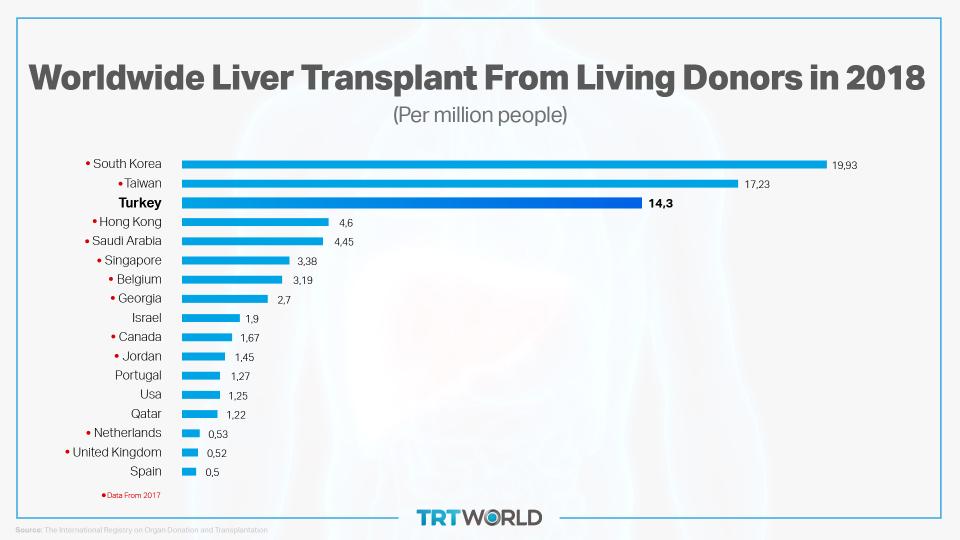

Thanks to Tokat and his other courageous and capable colleagues, Turkey has made an incredible improvement in the liver transplant industry, where the country is counted among the top three countries in the world in terms of recording the most liver transplant operations along with India and South Korea. (Musab Abdullah Gungor / TRTWorld)

(Musab Abdullah Gungor / TRTWorld)

Turkey’s success rate is also quite high in terms of live donor liver transplantation (LDLT), reaching 80 to 90 percent, according to Tokat. With the help of the Turkish health ministry, which accelerated its support to the industry in 2010, 49 liver transplant departments continue to operate across the country with varying degrees of success.

“The state’s decision to fully support organ transplantation ten years ago was a very big step. But we also need to implement that decision in a proper sense,” Tokat says.

“Turkey’s decision at the time was probably one of the best steps ever taken in the world, as it aimed to make all organ transplants free for all patients no matter where operations are done,” he sees.

“We grew up reading books in English and going to Western countries to learn more about the transplantation industry. But now, American and British surgeons are coming to Turkey to get training from us to learn more about LDLT operations,” he says.

The following year, in 1999, his team conducted Turkey’s first successful LDLT operation, taking the country to the new age of both organ donation and the LDLT. Both the techniques became popular in Turkey for reasons ranging from religious considerations to close family relations.

“We began doing like 100 operations per year,” Tokat says, referring to a period between 1999 and 2005, when he decided to move the whole liver transplant program to Istanbul’s Florence Nightingale Hospital. For 15 years, his team had worked there until he decided to establish a new center, International Liver Center, this year. He now performs all the liver transplantation operations in his new center.

More than three decades after he conducted the first kidney transplant operation in Izmir, Tokat is now considered to be one of Turkey’s leading liver transplant surgeons, who is also well-known across the world and has earned the reputation of being a fearless surgeon. Since 1994, he has done more than 1,500 liver transplants. He once performed 143 surgeries a year, he recalls.

Turkey: a rising star

Thanks to Tokat and his other courageous and capable colleagues, Turkey has made an incredible improvement in the liver transplant industry, where the country is counted among the top three countries in the world in terms of recording the most liver transplant operations along with India and South Korea.

(Musab Abdullah Gungor / TRTWorld)

(Musab Abdullah Gungor / TRTWorld)Turkey’s success rate is also quite high in terms of live donor liver transplantation (LDLT), reaching 80 to 90 percent, according to Tokat. With the help of the Turkish health ministry, which accelerated its support to the industry in 2010, 49 liver transplant departments continue to operate across the country with varying degrees of success.

“The state’s decision to fully support organ transplantation ten years ago was a very big step. But we also need to implement that decision in a proper sense,” Tokat says.

“Turkey’s decision at the time was probably one of the best steps ever taken in the world, as it aimed to make all organ transplants free for all patients no matter where operations are done,” he sees.

“We grew up reading books in English and going to Western countries to learn more about the transplantation industry. But now, American and British surgeons are coming to Turkey to get training from us to learn more about LDLT operations,” he says.

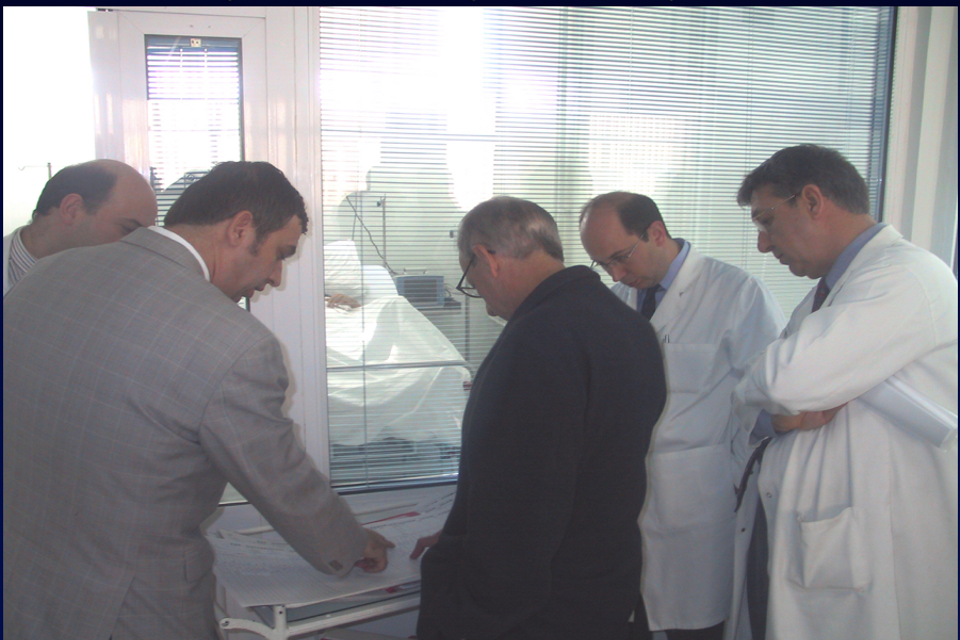

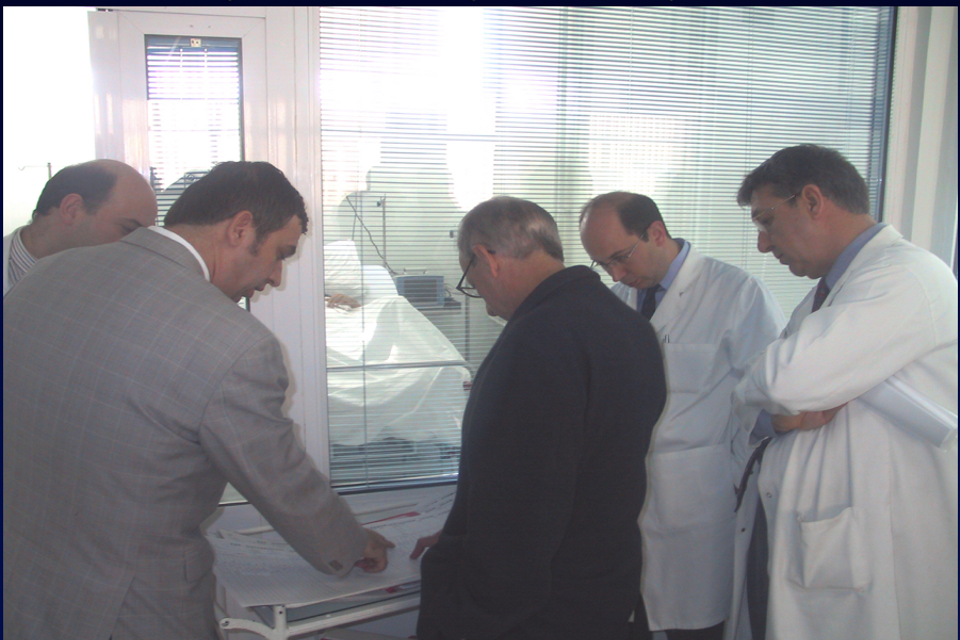

In the Ege University in Izmir in 2002, Professor Yaman Tokat discusses with Ronald W. Busuttil, a well-known American professor, who is also the Dumont Professor of Transplantation Surgery and Chief of the Division of Liver and Pancreas Transplant in the Department of Surgery at the UCLA School of Medicine. (Credit: Yaman Tokat / TRTWorld)

Due to the pandemic, Turkey has particularly become an attractive destination for liver transplant operations, as Europe and the US have imposed various travel restrictions preventing people from considering them as an option.

“In LDLT operations, we are much better than Germany, Britain and the US. Our operational costs are also much lower than those countries. Due to the pandemic, India and China have also lost their appeal, making Turkey one of the best destinations for health tourism,” he says.

Tokat and his colleagues also established the International Liver Surgeons Union, where he is the deputy chairman now, bringing out many top liver transplant surgeons across the world. With his International Liver Center, which he ultimately wants to evolve into a university, Tokat aims to collect various data from different cases and a wide range of experiences from Turkey and the world.

“We want to leave Turkey a perpetual legacy and a large collection of data,” he says. If his centre turns into an international medical body, where the world’s top surgeons could find their voice, many patients across the globe would choose Turkey as their ultimate destination to cure liver diseases then, he believes. (Musab Abdullah Gungor / TRTWorld)

(Musab Abdullah Gungor / TRTWorld)

“Now I want to run for this dream. If you have dreams, you can find meaning in life,” he says.

Imagination is crucial for continuity, he says, recalling how modern medics in the early 1900s first thought about the possibility of organ transplant by seeing ancient pictures of mythological animals, who were kind of eclectic or hybrid entities created by using different body parts of different animals.

Tokat and his colleagues want to develop an international liver transplant centre, which could be an attractive point for Turkey’s surrounding region from the Balkans to the Middle East and Central Asia.

A man of discipline and principle

While Tokat is now undoubtedly one of the biggest names in the liver transplant industry, he appears to have lost no love for what he does.

Tokat, a Turkish word which also means a slap in English language, comes across as a passionate man, who's deeply devoted to his job, liver transplant, one of the hardest surgical procedures, which saves thousands of lives every year.

But he doesn't like to attribute his success to the word 'passion'. Instead, he credits Tekdogan for shaping his career, as well as his middle-class background, which taught him to be honest and ethical no matter what.

“I began my career not as a passionate man but as a man on a mission,” he says, referring to the roots of his Turkish model. “I began this job because my teacher told me ‘Come and start this job’”.

“After my decades-long labour, I have also developed a love for my occupation. You love something if you labour so hard for it. If you don’t labour anymore, love breaks up,” he says.

“As much as I succeed, I learn more and help others and my occupation has turned into a passion for me, making myself a role-model for our society”.

Source: TRT World

Due to the pandemic, Turkey has particularly become an attractive destination for liver transplant operations, as Europe and the US have imposed various travel restrictions preventing people from considering them as an option.

“In LDLT operations, we are much better than Germany, Britain and the US. Our operational costs are also much lower than those countries. Due to the pandemic, India and China have also lost their appeal, making Turkey one of the best destinations for health tourism,” he says.

Tokat and his colleagues also established the International Liver Surgeons Union, where he is the deputy chairman now, bringing out many top liver transplant surgeons across the world. With his International Liver Center, which he ultimately wants to evolve into a university, Tokat aims to collect various data from different cases and a wide range of experiences from Turkey and the world.

“We want to leave Turkey a perpetual legacy and a large collection of data,” he says. If his centre turns into an international medical body, where the world’s top surgeons could find their voice, many patients across the globe would choose Turkey as their ultimate destination to cure liver diseases then, he believes.

(Musab Abdullah Gungor / TRTWorld)

(Musab Abdullah Gungor / TRTWorld)“Now I want to run for this dream. If you have dreams, you can find meaning in life,” he says.

Imagination is crucial for continuity, he says, recalling how modern medics in the early 1900s first thought about the possibility of organ transplant by seeing ancient pictures of mythological animals, who were kind of eclectic or hybrid entities created by using different body parts of different animals.

Tokat and his colleagues want to develop an international liver transplant centre, which could be an attractive point for Turkey’s surrounding region from the Balkans to the Middle East and Central Asia.

A man of discipline and principle

While Tokat is now undoubtedly one of the biggest names in the liver transplant industry, he appears to have lost no love for what he does.

Tokat, a Turkish word which also means a slap in English language, comes across as a passionate man, who's deeply devoted to his job, liver transplant, one of the hardest surgical procedures, which saves thousands of lives every year.

But he doesn't like to attribute his success to the word 'passion'. Instead, he credits Tekdogan for shaping his career, as well as his middle-class background, which taught him to be honest and ethical no matter what.

“I began my career not as a passionate man but as a man on a mission,” he says, referring to the roots of his Turkish model. “I began this job because my teacher told me ‘Come and start this job’”.

“After my decades-long labour, I have also developed a love for my occupation. You love something if you labour so hard for it. If you don’t labour anymore, love breaks up,” he says.

“As much as I succeed, I learn more and help others and my occupation has turned into a passion for me, making myself a role-model for our society”.

Source: TRT World