by Robin Millard

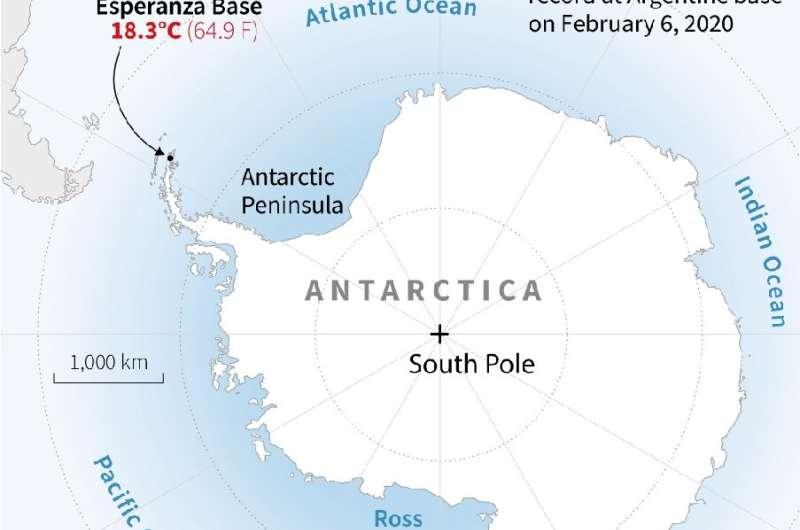

The United Nations on Thursday recognised a new record high temperature for the Antarctic continent, confirming a reading of 18.3 degrees Celsius (64.9 degrees Fahrenheit) made last year.

The record heat was reached at Argentina's Esperanza research station on the Antarctic Peninsula on February 6, 2020, the UN's World Meteorological Organization said.

"Verification of this maximum temperature record is important because it helps us to build up a picture of the weather and climate in one of Earth's final frontiers," said WMO secretary-general Petteri Taalas.

"The Antarctic Peninsula is among the fastest-warming regions of the planet—almost 3C over the last 50 years.

"This new temperature record is therefore consistent with the climate change we are observing."

The WMO rejected an even higher temperature reading of 20.75C (69.4F), reported on February 9 last year at a Brazilian automated permafrost monitoring station on the nearby Seymour Island, just off the peninsula which stretches north towards South America.

The previous verified record for the Antarctic continent—the mainland and its surrounding islands—was 17.5C (63.5F) recorded at Esperanza on March 24, 2015.

The record for the wider Antarctic region—everywhere south of 60 degrees latitude—is 19.8C (67.6F), taken on Signy Island on January 30, 1982.

Verification process

In checking the two reported new temperature records, a WMO committee reviewed the weather situation on the peninsula at the time.

It found that a large high-pressure system created downslope winds producing significant local surface warming.

Past evaluations have shown that such conditions are conducive for producing record temperatures, the WMO said.

The experts looked at the instrumental set-ups and the data, finding no concerns at Esperanza.

However, an improvised radiation shield at the Brazilian station on Seymour Island led to a demonstrable thermal bias error for the permafrost monitor's air temperature sensor, making its reading ineligible to be signed off as an official WMO weather observation.

The new record at Esperanza will be added to the WMO's archive of weather and climate extremes.

The archive includes the world's highest and lowest temperatures, rainfall, heaviest hailstone, longest dry period, maximum gust of wind, longest lightning flash and weather-related mortalities.

The lowest temperature ever recorded on Earth was minus 89.2C (minus 128.6F) recorded at Vostok station in Antarctica on July 21, 1983.

Global warming concerns

Antarctica's average annual temperature ranges from about minus 10C (14F) on the coast to minus 60C (minus 76F) at the highest parts of the interior.

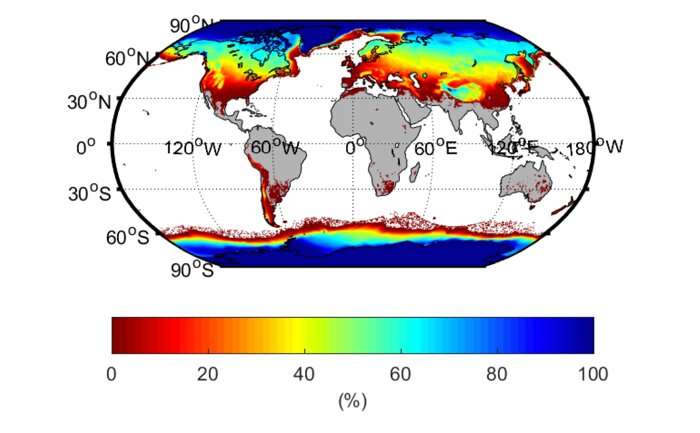

"Even more so than the Arctic, the Antarctic is poorly covered in terms of continuous and sustained weather and climate observations and forecasts, even though both play an important role in driving climate and ocean patterns and in sea level rise," said Taalas.

The Earth's average surface temperature has gone up by 1C since the 19th century, enough to increase the intensity of droughts, heat waves and tropical cyclones.

But the air over Antarctica has warmed more than twice that much.

Recent research has shown that warming of two degrees Celsius could push the melting of ice sheets atop Greenland and the West Antarctic—with enough frozen water to lift oceans 13 metres (43 feet)—past a point of no return.

"This new record shows once again that climate change requires urgent measures," said WMO first vice president Celeste Saulo, the head of Argentina's national weather service.

"It is essential to continue strengthening the observing, forecasting and early warning systems to respond to the extreme events that take place more and more often due to global warming."

Explore furtherAntarctica registers record temperature of over 20 C

© Reuters/DARRIN ZAMMIT LUPI FILE PHOTO: The logo of Binance is seen on their exhibition stand at the Delta Summit, Malta's official Blockchain and Digital Innovation event promoting cryptocurrency, in St Julian's

© Reuters/DARRIN ZAMMIT LUPI FILE PHOTO: The logo of Binance is seen on their exhibition stand at the Delta Summit, Malta's official Blockchain and Digital Innovation event promoting cryptocurrency, in St Julian's