Opening at the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris in November and set to run until March this year, Juifs d’Orient – Jews of the Orient – is the Institut’s main winter exhibition.

It was planned and put together by a mostly French group of curators headed by Franco-Algerian scholar Benjamin Stora, himself the author of several works on Algeria’s former Jewish community, and it represents a kind of logistical triumph since the several hundred items on show have been brought together from public and private collections in some half a dozen countries, all under the difficult circumstances of the ongoing pandemic of Covid-19.

It is a survey exhibition taking in a vast geographical area – the Orient of the title turns out to refer to most of the Middle East as well as the Arab Maghreb and even beyond – as well as some three millennia of history. It includes material relating to the earliest Jewish communities in the wider Middle East in the first millennium BCE and to the much later dispersal of such communities in the wake of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.

Given this geographical and temporal scope, the exhibition cannot say much about any one community, though there is some focus on the more modern period and the Jewish communities of the former Ottoman Empire in its later parts, possibly because of the relative abundance and greater variety of the material that can be put on show.

Overall, the intention has been to trace the history of the Jews of the Arab world mostly over the past millennium with some side glances at Jewish communities in the non-Arab Middle East such as in some former Ottoman territories as well as in Iran. It picks out some important moments from this history, one such being the close relationship between Muslims and Jews in Al-Andalus (Arab Spain) from around the 10th to the 15th century. An important representative of this was the Arab Jewish philosopher and theologian Maimonides (Moses ben Maimon or Mousa ibn Maimoun), born in Cordoba in southern Spain in 1138, writing largely in Arabic, and later moving to Cairo to become a leading figure of the city’s Jewish community.

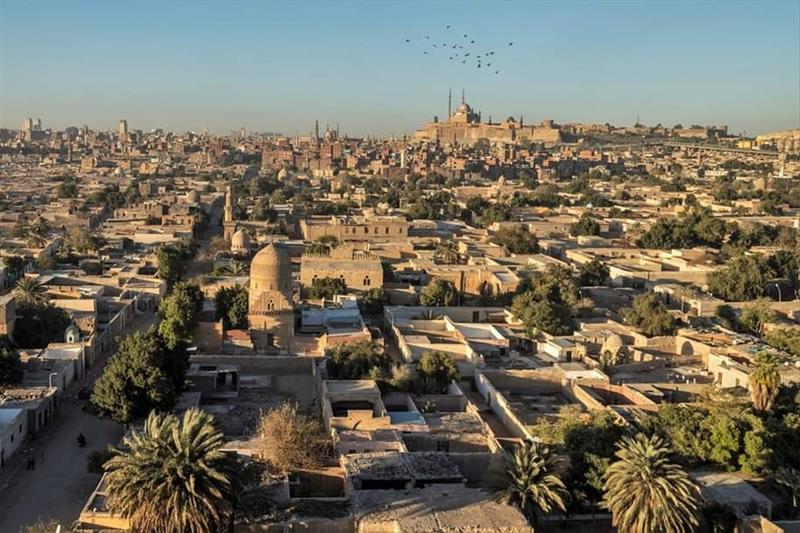

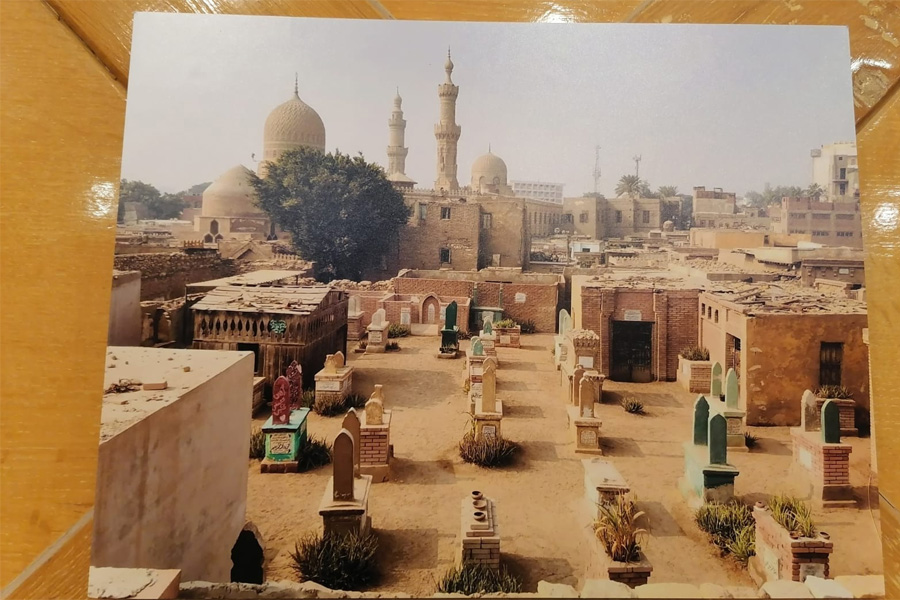

Another important moment took place in Cairo itself, where the city’s Jews flourished under first Fatimid and then Ayyubid and Mameluke rule especially between the 10th and 14th centuries. A great deal is known about this community, along with its connections to the wider world, because of the discovery of a unique set of documents in a storeroom leading off the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Old Cairo at the end of the 19th century. This material, known as the Geniza documents, only survived because of the community’s habit of not destroying any written documents, instead discarding them to build up what eventually became an enormous mound of paper.

When this was excavated and studied, it turned out to contain documents of great importance, such as texts by Maimonides written in his own hand, along with others that might seem to be of little intrinsic interest, such as commercial correspondence along with other humdrum materials relating to everyday life, but that could yield important information to historians. By studying the Geniza documents the US-based German historian S D Goitein was able to reconstruct what he called a whole “Mediterranean society” based in Cairo.

A third focus of the exhibition is on the Sephardic Jews, those who in the main traced their origins back to formerly Arab Spain until they were expelled from the country, along with Spain’s Muslims, in 1492. Many members of the Jewish communities that were such a feature of many of the large urban centres of the former Ottoman Empire were of Sephardic origin, including Arab centres such as Baghdad and Cairo, along with non-Arab Mediterranean centres such as Salonica (Thessaloniki), now in Greece but until 1913 part of the Ottoman Empire, and of course also Istanbul.

They added to the pre-existing Jewish communities in these areas, some of them flourishing in mediaeval times such as Cairo’s Geniza Jews and some tracing their origins even further back to earlier periods when they lived under ancient Roman or other rule.

Overall, while some of the material included in the exhibition will be familiar to many, seeing it presented together provides considerable food for thought. While at times some parts of the Jewish communities of the Arab world may have kept aloof from their Muslim and Christian compatriots, perhaps especially during the final stages of European colonial rule, more often they were integrated into a common Arab civilisation, sharing its language and non-religious aspects of its culture and making many contributions to cultural, political, and economic life.

The kind of persecution of the Jews that historically was such a feature of many European societies did not exist in the Arab countries or the Islamic world, perhaps partly to be put down to the fact that the Jews like the Christian religious minorities had a clearly defined legal status that gave them rights as well as responsibilities and guaranteed their position in the wider society.

MILLENNIAL HISTORY

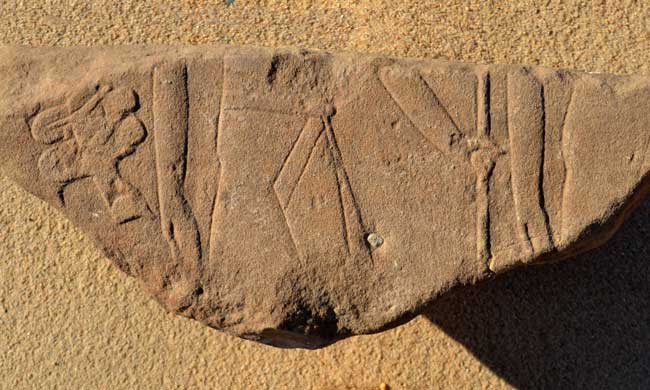

The exhibition begins with early items such as papyrus documents written in Aramaic recording contracts between members of the Jewish community in Elephantine in Upper Egypt dating from the Sassanid period in the 5th century BCE.

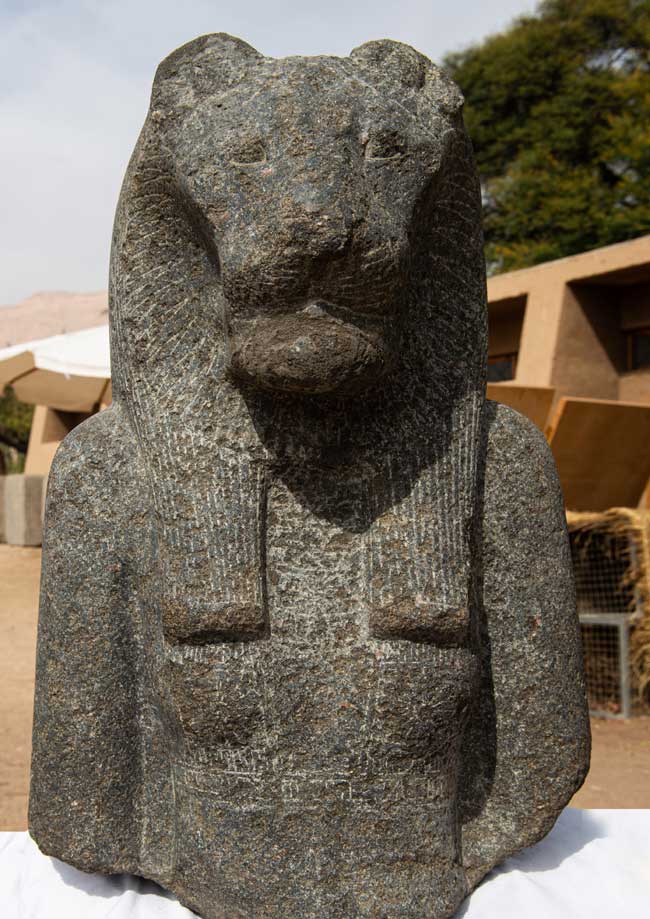

There are architectural and other elements from early synagogues, including mosaics from the 4th-century CE Naro Synagogue (today’s Hammam Lif) in Tunisia and images of wall paintings from the 3rd-century CE Synagogue of Dura Europos, a Hellenistic and later Roman city in the Syrian desert the remains of which were excavated in the last century. Photographs of parts of the Hijaz in the west of today’s Saudi Arabia suggest the environment of the early Jewish settlements of this region, whose inhabitants are mentioned in the Quran.

The exhibition continues into periods having more written records, looking first at the Jewish communities of Arab Spain and then at documents from the Cairo Geniza. Writing of the former in the exhibition catalogue, US academic David Wasserstein says that the Arab conquest of Spain in the 8th century CE led to a remarkable renaissance of Jewish life since “in becoming part of Arab-Muslim civilisation, the Jews were able not only to travel from Spain to as far afield as India,” since they were members of a common cultural space, but they were also “able to actively participate in the economic and cultural life of this vast area through the common use of Arabic.”

Writing of the Cairo Geniza documents also in the exhibition catalogue, US academic Mark Cohen says that these show the presence of “Jews working side by side with Muslims at almost every level of society…They were artisans, civil servants, doctors, and members of other professions also exercised by Muslims. Their intellectual elites naturally shared the same interests, for example in philosophy, as their Muslim peers, and their doctors took care of the same patients in the same multi-faith hospitals.”

Following the expulsion of the Jews from Spain, many went to Morocco where a distinction grew up, the exhibition says, between native Moroccan, mostly Berber, Jews and the newer Sephardic Jews. Important communities grew up in the central Moroccan city of Fes, as well as in northern and southern coastal towns such as Tangiers, Tetouan, and Mogador (Essaouira). Other Sephardic Jews went to cities throughout the Ottoman Empire, where they established themselves in various industries, as well as in international trade.

A large section of the exhibition is given over to what it calls the “period of Europe” when growing European intervention in the Arab world from the 19th century onwards produced first colonialism and then national-liberation movements intended to throw off European colonial rule. For the Jewish communities of the Arab world, this reorganisation of relations between east and west, associated with a general weakening of the Ottoman Empire and a rewriting of its societal rules, had ambiguous results, the exhibition says.

Some Jews shared in a new prosperity impacting the empire’s commercial classes, while others became more detached from their Arab environment, in some cases the result of deliberate policy adopted under European rule.

According to Israeli historian Michel Abitbol writing in the exhibition catalogue, such processes were particularly at work in the Arab Maghreb countries of Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia under French rule. “More and more Jews left their traditional districts – the hara and mellah [of traditional towns and cities] – to live in the new mostly European areas,” he writes.

More and more started to receive a European-style education, notably through the French-sponsored Alliance Israelite Universelle schools, and more and more expressed themselves more readily in French than in Arabic. In Algeria, the Jews were given French citizenship in 1870, seen by some, Abithol says, as an indication “of their collusion with European colonial rule.”

Things were different in the east of the Arab world, though here too it seems that the Jewish communities of countries such as Iraq and Egypt, while present in these countries for millennia, or centuries in the case of the Sephardic Jews, were increasingly seen as somehow linked to foreign influence. Despite the efforts of many to prove their Arab belonging, in some cases playing important roles in nationalist struggles particularly on the left, they found themselves in a precarious position in states increasingly practising a revolutionary style of politics suspicious of anyone considered as being linked to European colonialism.

Increasing tensions linked to Zionism in Palestine and the 1948 Arab-Israeli War made many Jews want to leave, the exhibition notes in its final sections. The accompanying text says that whereas in 1945 “the Jewish population of the Arab-Muslim countries was around a million,” today the only Arab country having a significant Jewish community is Morocco. There are photographs and other materials bearing witness to the movement of populations of the time.

While the exhibition surveys several millennia of the history of the Jews of the Arab world, its last sections on their departure from the Arab countries after the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, which also gave rise to hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees, has caused most controversy. Many Arab public figures have criticised the Institut du Monde Arabe’s collaboration with Israeli institutions on the exhibition in a widely circulated open letter quoted in the French newspaper Le Monde on 13 December.

Juifs d’Orient, Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris, until 13 March 2022.

***

Among the more intriguing exhibitions on aspects of the Arab and Islamic world in Paris this winter is a major show at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, the Decorative Arts Museum that is part of the Louvre, on the relationship between French high-end jewellery maker Cartier and traditional Islamic art.

While the exhibition, called Cartier et les arts de l’Islam, aux sources de la modernité and running until February, seems likely to attract mostly visitors interested in Cartier jewellery and its relationship to modern French and European jewellery design, it turns out to be perhaps surprisingly interesting even to those ordinarily not particularly taken by such matters.

Coproduced with the Dallas Museum of Art in the US and with the support of the Cartier company, it extends an argument already pursued in an earlier exhibition at the same museum that looked at the ways in which traditional motifs from Islamic art were incorporated into European design from around the mid-19th century onwards, eventually giving rise to a whole range of European-produced objects with an Islamic flavour, from architectural elements to tea sets, wallpaper, and kitchenware.

This earlier exhibition, entitled Purs Décors? (“Just Decoration?”) and reviewed in Al-Ahram Weekly in November 2007, showed how the European encounter with Islamic art, perhaps beginning with the rediscovery of the Alhambra Palace in southern Spain in the early 19th century and increasing as more and more Europeans visited Cairo and elsewhere in the Middle East, led to the publication of growing numbers of illustrated books that could be mined for design ideas.

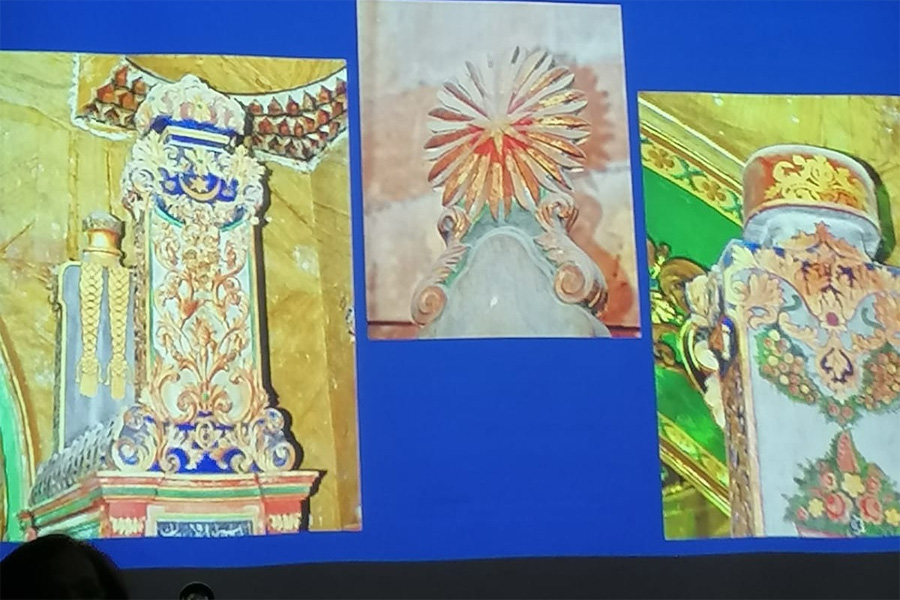

There was Englishman Owen Jones’ Grammar of Ornament, for example, published in 1856, and L’art arabe d’après les monuments du Caire, a survey and source book for architectural design by Frenchman Emile Prisse d’Avennes published between 1869 and 1877. Jones’ Grammar, a kind of pattern-book, provided examples of the Islamic style of geometric decoration found at the Alhambra Palace and elsewhere, while Prisse d’Avennes’ survey of Arab art fed the growing vogue for Islamic architectural decoration that had already been primed by its careful reproduction in the works of the 19th-century French orientalist painter Jean-Léon Gérôme.

The present exhibition is a kind of continuation of the earlier argument, showing how the Cartier company, looking round for new ideas at the beginning of the 20th century, hit upon the growing vogue for Islamic design. There were numerous exhibitions of Islamic art in Paris before World War I, the exhibition says, and there was a growing vogue for objects drawing on Islamic design.

There was an exhibition of Islamic art at the Louvre in 1903, for example, curated by Gaston Migeon, co-author of a Manuel d’art musulman in 1907 that also figures in the present exhibition. Three years later, there was a larger exhibition of Islamic art in Munich in Germany bringing together some 3,600 objects from across the Arab and Islamic world.

At the same time, there was Joseph-Charles Mardrus’ French translation of the Thousand and One Nights published in Paris between 1898 and 1904 that also fired up European interest in the Arab world. It served as additional inspiration for impresario Serge Diaghilev’s production of Russian composer Rimski-Korsakov’s Scheherazade for the Ballets Russes in Paris in the early years of the century, and it is also mentioned in the novel A la recherche du temps perdu by French author Marcel Proust.

It was against this background of heightened interest that traditional motifs from Islamic art were adopted by European designers who stripped them of their association with the traditional arts and crafts of the Islamic world and incorporated them into self-consciously modern European designs. It is for this reason that the exhibition is subtitled aux sources de la modernité – the origins of modernity – since Islamic art, traditional in Islamic societies, became modern in European.

Cartier, though already well-established by the turn of the 20th century and soon to be a favoured supplier of various European monarchs, was looking for ways to differentiate its products from those of its competitors while at the same time producing jewellery that was resolutely not Victorian in style. Jewellery that drew on Islamic design motifs answered to the general early 20th-century European injunction to “make it new,” the exhibition says.

Visitors to the exhibition can see the results of this quest in several hundred pieces taken from the Cartier collection and dating from the early 1900s to the 1930s, 1940s, and beyond, as well as in the materials that were mined for inspiration in the form of photographs of Islamic mosques and madrasas in a range of countries, objects gleaned from foreign tours, and books and articles on Islamic art and architecture all in the main taken from the Cartier archives.

The company itself was undergoing a process of renovation at more or less the same time, as the patriarch of the firm, Alfred Cartier, began to pass on responsibility for its commercial strategy and design ideas to his sons Pierre, Louis, and Jacques Cartier. While the former turned out to have a genius for strategy, with Cartier opening branches in London and New York in the early 1900s and giving the firm an international profile, the latter two brothers, especially Louis, were in charge of updating and developing its designs.

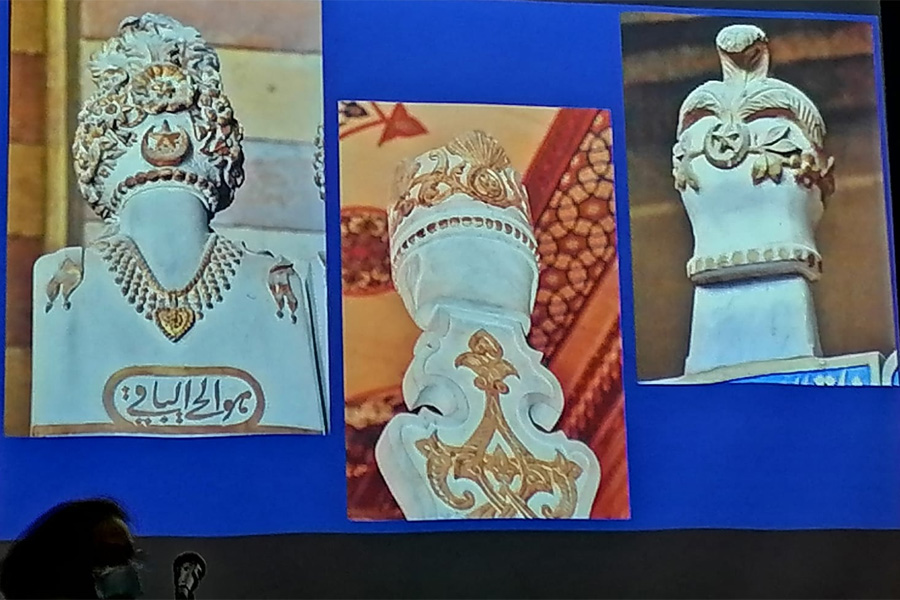

Louis put together his own collection of Islamic art as well as of books and photographs of Islamic crafts and architecture that could be mined for design ideas. Jacques visited the Middle East and northern India on multiple occasions in search of pearls and precious stones and textiles. Some of these materials as well as objects from Louis’ collection have been placed on show in the Paris exhibition along with the Cartier designs they inspired.

ISLAMIC DESIGN

The exhibition is arranged around a darkened double-volume central space featuring large projections wonderfully realised by the US design firm DS+R and showing in detail how motifs from traditional Islamic art and architecture found their way into Cartier jewellery designs.

Rooms around the edges begin by exploring the early 20th-century context and the growing appeal of Islamic art in Europe before focusing on objects from Louis Cartier’s own collection of Islamic art and the books and photographs from his library that he made available as sources of inspiration to the firm’s designers. Among the latter was lead designer Charles Jacqueau, responsible over several decades for many stand-out Cartier designs. Drawings by him are included in the exhibition, sometimes alongside photographs of the objects that inspired them, together with pages from Louis Cartier’s own notebooks.

Much of the detail here is fascinating, and curators Evelyne Possémé and Judith Henon-Raynaud must be congratulated for their sleuthing in the Cartier archives. This has turned up many hitherto unsuspected allusions, such as a 14th-century star shaped decorative tile from Iran, now in the Louvre but previously in the Louis Cartier collection, providing the geometrical outlines for a 1907 Cartier platinum and diamond pendant, or a section of 18th-century Egyptian mashrabiyya – the turned wood panelling typically used for window screens – inspiring a 1907 Cartier platinum, sapphire, and diamond brooch.

Other examples include architectural motifs found in the 1883 book Ornements arabes, a copy of which Louis Cartier owned, later turning up in miniature form in a 1923 Cartier platinum and diamond headband. Or the shape of the arcades in the Moti Masjid, the Pearl Mosque, in the Agra Fort near Delhi in India, similarly suggesting a solution to the problem of how to create running designs. Another example is the way in which the repeated shapes used in a 1924 Cartier platinum and diamond headband originally commissioned by the mother of US tobacco heiress Doris Duke were suggested by an illustration in British author Thomas Hendley’s 1909 survey of Indian Jewellery.

Henon-Raynaud writes that this book, much studied by Louis Cartier, included illustrations of the headbands traditionally worn by the Hazara people of Afghanistan. “The highly flexible structure of these inspired the rigid 1924 headband [made for Nanaline Duke], where the lozenge motif is repeated and encrusted with diamonds,” she says.

A 1902 gold, silver, and diamond pendant was inspired by an Iranian original seen hanging from the waistband of an early 19th-century portrait of Persian shah Fath Ali Shah in the Louvre, as was a platinum and diamond bazuband, a kind of upper-arm bracelet, commissioned by Indian millionaire Sir Dhunjibhoy Bomanji in 1922. However, it was not only jewellery that was inspired by originally Islamic designs, since Cartier also used motifs and design principles gleaned from traditional Islamic art for a range of other objects, including cigarette and vanity cases.

An exquisite gold and lapis lazuli cigarette case made in 1930 by the Paris branch of the firm provides much of the advertising for the exhibition, and it turns out that its use of repeated gold-and-blue motifs was taken from Islamic architectural decoration found reproduced in a volume published in French in St Petersburg in 1905 called Les Mosquées de Samarcande. These famous mosques, clad in blue and green tiles featuring repeated geometrical designs, provided inspiration for the colour palette and decorative principles used by Cartier.

Other cigarette cases and similar items used motifs taken from traditional Islamic bookbinding. The decorative binding of a copy of poems by the Persian poet Saadi made for sultan Abdel-Aziz of Bukhara in Central Asia in 1531 and formerly in Louis Cartier’s collection suggested the design of a 1928 Cartier New York gold, coral, and platinum cigarette case, for example. The kind of decoration typically found on a whole range of objects of Islamic art was borrowed and repurposed by Cartier to solve the problem of how to cover flat surfaces with continuously interesting repeating motifs.

Scrupulously researched and beautifully designed, the exhibition shows in detail how one major European firm drew on and was inspired by traditional Islamic art and architecture as part of a larger project to reinvigorate and find fresh ideas for self-consciously modern European designs. In this case, the intention was to find new sources of inspiration for jewellery, but similar exhibitions could be mounted for other later 19th-century and early 20th-century European arts, as indeed the Musée des Arts Décoratifs has already done in its earlier exhibition Purs Décors?

“In the relations between the Western world and the societies beyond its borders, the civilisation of Islam occupies a singular place,” the catalogue to the exhibition comments, “owing not only to its geography, stretching from the Mediterranean to more distant lands and from Andalusia in southern Spain to India, but also to its many diverse cultural facets,” among them the traditions of Islamic art.

One way of thinking about these relations has wanted to emphasise the European colonialism of the 19th and early 20th centuries, reducing them to matters of power or cultural appropriation. In fact, as this exhibition shows, things were always more complicated than that, with Islamic art being an important factor in the renovation of European art and not, as one author quoted in the exhibition puts it, so much a “passive object of study as an active subject of exchange.”

Cartier et les arts de l’Islam, aux sources de la modernité, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, until 20 February 2022.

*A version of this article appears in print in the 27 January, 2022 edition of Al-Ahram Weekly.