New life cycle assessment study shows useful life of tech-critical metals to be short

Worldwide, almost all technology-intensive industries depend on readily available metallic raw materials. Consequently, precise and reliable information is needed on how long these raw materials remain in the economic cycle. To obtain the necessary data, a research team from the universities of Bayreuth, Augsburg and Bordeaux has now developed a new modeling method and applied it to 61 metals. The study, published in Nature Sustainability, shows that the metals needed for specific high-tech applications, which in many cases are scarce around the world, are in use for only a decade on average.

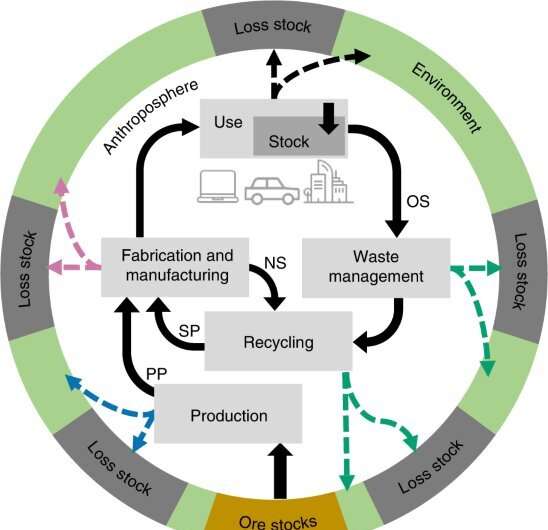

The useful life of a metal comprises the entire period that begins with mining and ends when it dissipates—i.e., is finely dispersed—in the environment, and is no longer available for economic use. Iron and steel alloy metals have the longest useful life, averaging 150 years. The researchers see the reason for this primarily in the high efficiency of the industrial processes in which these metals are processed, as well as in high recycling rates. The lifespan of non-ferrous metals such as aluminum and copper and precious metals such as gold and silver is significantly shorter, but it is still over 50 years. By contrast, the technology-specific and in some cases critical—i.e. hardly available—metals only remain in the economic cycle for about twelve years. Cobalt and indium are examples of this large group of raw materials. For all these calculations, data from the Bureau de Recherches Géologiques et Minières (BRGM), a geoscientific institute based in Paris and Orléans, was used.

One thing all of the 61 metals studied have in common is that the quantities lost to the economic cycle over time must be constantly compensated for by new mining. The greater the losses, the more resources are irretrievably lost, and the more damaging the consequences are for the climate and the environment.

"It is in the urgent interest of the world's population to extend the useful life of metals and to strive for economic cycles that are as closed as possible to prevent these huge losses. However, these goals can only be achieved if the useful life of every raw material relevant to our technology can be extended and calculated with greater statistical accuracy," says Prof. Dr. Christoph Helbig, Chair of the newly established Ecological Resource Technology research group at the University of Bayreuth. The aim of his research is to increase the useful life of metallic resources, and in this way contribute to environmentally and climate-friendly industries.

The calculations now published in Nature Sustainability are based on a new modeling method developed by the authors, with which the useful life of metals can be calculated far more reliably than with the usual measurements based on recycling rates. The special feature of this statistical method is that it can be applied equally to almost all metals of the periodic table. This is a decisive prerequisite for the data obtained to be comparable. Only in this way can they form a reliable basis for life cycle assessments that provide information on the extent to which valuable raw materials are being used efficiently or wasted. Life cycle assessments in the area of abiotic raw materials look set to be considerably more meaningful thanks to the research results achieved by the study.

Prof. Dr. Christoph Helbig started work on the new study while still at the University of Augsburg and brought the topic to Bayreuth: "I am very much looking forward to continuing and developing the existing cooperation with working groups in Bordeaux and Augsburg at the University of Bayreuth," says Helbig. The University of Bordeaux is one of the partner institutions of the Gateway Office which the University of Bayreuth set up two years ago to further expand its international networking in research and teaching.New technology dramatically increases the recovery rate of precious metals

information: Alexandre Charpentier Poncelet et al, Losses and lifetimes of metals in the economy, Nature Sustainability (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41893-022-00895-

Journal information: Nature Sustainability

Provided by University of Bayreuth