The octopus’ brain and the human brain share the same “jumping genes”

A new study has identified an important molecular analogy that could explain the remarkable intelligence of these invertebrates

Peer-Reviewed PublicationIMAGE: DRAWING OF AN OCTOPUS view more

CREDIT: GLORIA ROS

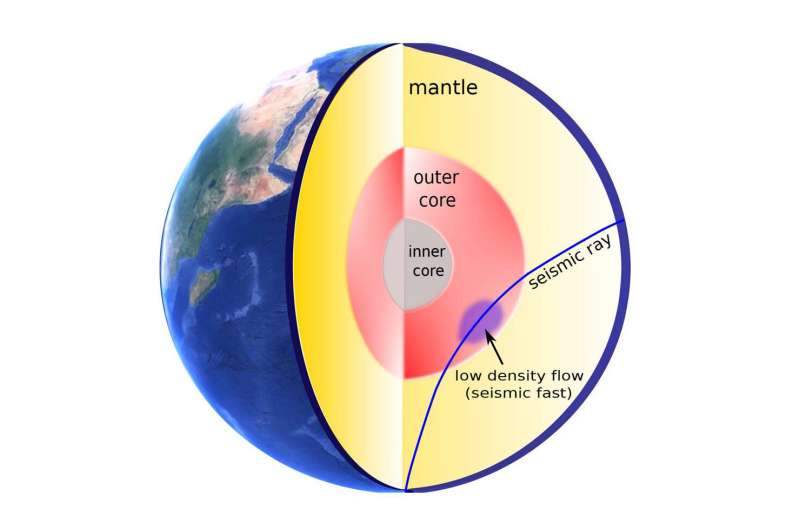

The octopus is an exceptional organism with an extremely complex brain and cognitive abilities that are unique among invertebrates. So much so that in some ways it has more in common with vertebrates than with invertebrates. The neural and cognitive complexity of these animals could originate from a molecular analogy with the human brain, as discovered by a research paper recently published in BMC Biology and coordinated by Remo Sanges from SISSA of Trieste and by Graziano Fiorito from Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn of Naples. The research shows that the same 'jumping genes' are active both in the human brain and in the brain of two species, Octopus vulgaris, the common octopus, and Octopus bimaculoides, the Californian octopus. A discovery that could help us understand the secret of the intelligence of these fascinating organisms.

Sequencing the human genome revealed as early as 2001 that over 45% of it is composed by sequences called transposons, so-called 'jumping genes' that, through molecular copy-and-paste or cut-and-paste mechanisms, can 'move' from one point to another of an individual’s genome, shuffling or duplicating. In most cases, these mobile elements remain silent: they have no visible effects and have lost their ability to move. Some are inactive because they have, over generations, accumulated mutations; others are intact, but blocked by cellular defense mechanisms. From an evolutionary point of view even these fragments and broken copies of transposons can still be useful, as 'raw matter' that evolution can sculpt.

Among these mobile elements, the most relevant are those belonging to the so-called LINE (Long Interspersed Nuclear Elements) family, found in a hundred copies in the human genome and still potentially active. It has been traditionally though that LINEs’ activity was just a vestige of the past, a remnant of the evolutionary processes that involved these mobile elements, but in recent years new evidence emerged showing that their activity is finely regulated in the brain. There are many scientists who believe that LINE transposons are associated with cognitive abilities such as learning and memory: they are particularly active in the hippocampus, the most important structure of our brain for the neural control of learning processes.

The octopus’ genome, like ours, is rich in 'jumping genes', most of which are inactive. Focusing on the transposons still capable of copy-and-paste, the researchers identified an element of the LINE family in parts of the brain crucial for the cognitive abilities of these animals. The discovery, the result of the collaboration between Scuola Internazionale Superiore di Studi Avanzati, Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn and Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, was made possible thanks to next generation sequencing techniques, which were used to analyze the molecular composition of the genes active in the nervous system of the octopus.

“The discovery of an element of the LINE family, active in the brain of the two octopuses species, is very significant because it adds support to the idea that these elements have a specific function that goes beyond copy-and-paste,” explains Remo Sanges, director of the Computational Genomics laboratory at SISSA, who started working at this project when he was a researcher at Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn of Naples. The study, published in BMC Biology, was carried out by an international team with more than twenty researchers from all over the world.

“I literally jumped on the chair when, under the microscope, I saw a very strong signal of activity of this element in the vertical lobe, the structure of the brain which in the octopus is the seat of learning and cognitive abilities, just like thehippocampus in humans,” tells Giovanna Ponte from Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn.

According to Giuseppe Petrosino from Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn and Stefano Gustincich from Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia “This similarity between man and octopus that shows the activity of a LINE element in the seat of cognitive abilities could be explained as a fascinating example of convergent evolution, a phenomenon for which, in two genetically distant species, the same molecular process develops independently, in response to similar needs.”

“The brain of the octopus is functionally analogous in many of its characteristics to that of mammals,” says Graziano Fiorito, director of the Department of Biology and Evolution of Marine Organisms of the Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn. “For this reason, also, the identified LINE element represents a very interesting candidate to study to improve our knowledge on the evolution of intelligence.”

JOURNAL

BMC Biology

METHOD OF RESEARCH

Experimental study

SUBJECT OF RESEARCH

Animals

ARTICLE TITLE

Identification of LINE retrotransposons and long non-coding RNAs expressed in the octopus brain

MICHELLE STARR

23 JUNE 2022

Artist's impression of Vampyronassa rhodanica. (A. Lethiers, CR2P-SU)

A fearsome 'vampire' predator that lurked in Earth's oceans more than 160 million years ago probably did actually suck its prey, at least in a sense.

A new analysis of exceptionally well-preserved fossils of a small cephalopod named Vampyronassa rhodanica, related to modern vampire squids (neither actually vampires, nor squids), reveals the presence of muscular suckers that the beastie likely used for snaring and manipulating prey.

In other words, it was an active predator, hunting the pelagic depths for tasty morsels.

This is in direct contrast to the animal's present relatives, Vampyroteuthis infernalis, whose suckers seem largely non-functional, and which collect drifting flakes of organic material using sticky cells on a pair of specialized, thread-like appendages.

"The contrast in trophic niches between the two taxa is consistent with the hypothesis that these forms diversified in continental shelf environments prior to the appearance of adaptations in the Oligocene leading to their modern deep-sea mode of life," writes a team of researchers led by paleontologist Alison Rowe of Sorbonne University in France.

Mushy animals like cephalopods are pretty scarce in the fossil record. Soft tissues don't fossilize as readily or well as bones, which makes fossils, especially good fossils, very rare.

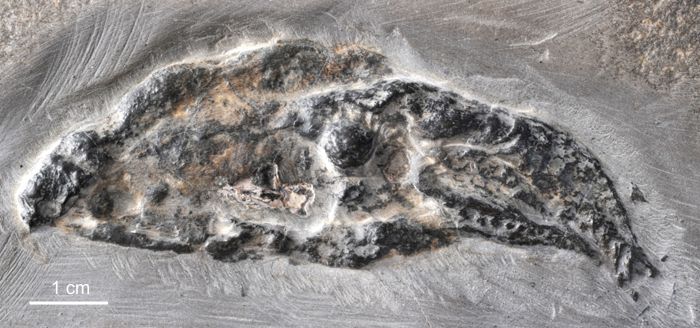

Rare doesn't mean nonexistent, however, and Rowe and her colleagues were able to study three V. rhodanica fossils from a lagerstätte (sedimentary deposit) dating back to over 160 million years ago in La Voulte-sur-Rhône in France. This is a type of very fine sedimentary fossil bed that is exceptionally good at preserving fossils, including soft tissue.

Even soft tissue preserved in this way isn't always easy to parse. To understand the anatomy of V. rhodanica, Rowe and her team took the fossils to the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in France to undergo non-invasive 3D imaging.

"The fossils are on small slabs, which are very difficult to scan," Rowe explains.

"On top of that, soft tissues are preserved but we needed phase contrast imaging to visualize the faint density variation in the data. The coherence of ESRF beamline ID19 was therefore very important to perform propagation phase-contrast computed-tomography and track all the minute details, such as the suckers and small fleshy extensions, called cirri."

The scans revealed some interesting differences between V. rhodanica and V. infernalis, which is now the only living member of the Vampyromorph order.

Both are relatively small (the former just 10 centimeters or 4 inches in length), with oval bodies flanked by two small fins. Both also have small, fleshy projections called cirri emerging from their arms.

Yet there were no signs of the thread-like food snares on any of the V. rhodanica fossils – instead an extended pair of arms with a unique arrangement of suckers.

On the tips of these two specialized dorsal arms, it sports more robust, muscular cirri and suckers. V. infernalis has smaller cirri, and its suckers appear only on the ends of their arms farthest from their bodies. What's more, they appear to be passive; it doesn't use them for grasping prey.

"We believe that the morphology and placement of V. rhodanica suckers and cirri in the differentiated arm crown allowed V. rhodanica increased suction and sensory potential over the modern form, and helped them to manipulate and retain prey," Rowe says.

In other words, V. rhodanica has the equipment to be an active predator in the pelagic seas, with more sensitive sensory organs and the ability to grasp prey. V. infernalis is more peaceful and opportunistic.

Although related, the two species occupy different ecological niches... neither of which is actually anything to do with vampirism. Oh well.

By the Oligocene, about 30 million years ago, vampire squids were already in the depths, lurking about, waiting for organic debris to rain down into their hungry arms.

Sometime in the intervening millions of years, vampire squids made a significant lifestyle change. How and why this happened will need to be the subject of future research… if the fossils can be found.

The team's research has been published in Scientific Reports.

New technology makes it possible to glean a lot more information from rare fossils.

By Grant Currin

The modern vampire squid is a cryptic creature. It lives a slow life deep in the ocean — far from shore — where it makes a living by scavenging on whatever dead things happen to sink past it on their journey to the ocean floor.

Was life always this way? That's a hard question to answer for animals like squid, octopuses, and cuttlefish because those creatures (a group of evolutionary cousins called "coleoids") are defined by what they don't have: a hard shell. That means they don't have body parts that lend themselves to becoming a fossil. Conditions have to be just right for a coleoid's soft body to make it into the fossil record.

That's why a new paper, published Thursday in the peer-reviewed journal Scientific Reports, is a big deal. Paleontologist Alison Rowe and her team used 3D imaging to analyze rare fossilized remains of an extinct relative of the vampire squid. Their findings suggest that Vampyronassa rhodanica may have been a bit more, well, vigorous. Their results point to a fearsome eight-armed hunter that likely captured prey with a pair of powerful suction cups.

Interesting Engineering sat down with Rowe to discuss the study, what they learned about Vampyronassa rhodanica, and what that new information reveals about the ancient oceans.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Interesting Engineering: How did you and your co-authors carry out this study?

Alison Rowe: In this study, we utilized powerful X-ray imaging techniques to scan fossil and modern specimens. This allowed us to observe previously unseen internal structures of the fossils, as well as view the external soft tissue anatomy with much better resolution.

From the comparative analysis between the fossil and extant form, we can show for the first time that there was a combination of anatomical characters in V. rhodanica that aren’t seen today. This research provides a small window on the diversity of character combinations that occurred in the Jurassic that are now lost.

IE: In the paper, you compare V. rhodanica to the modern-day vampire squid. For context, can you give us a crash course on the vampire squid and its relatives?

Rowe: The vampire squid is actually not a squid. It is closer to octopuses than to squids. Like the octopus, it has 8 arms, but also two filaments that are developmentally homologous to arms, which makes it somewhat comparable to squid or cuttlefish (Decabrachia) that have 10 arms. It has cirri on the arms like the incirrates [a suborder of the order Octopoda]. It has its own characteristics such as its type of sucker attachment, and its gladius, which is a kind of internal organic shell.

It is uniquely adapted to living in the deep sea, often in areas of low oxygen, and is an opportunistic detritivore, feeding on organic material falling through the water column.

IE: What samples did you use for this study?

Rowe: We reanalyzed 3 fossil specimens of Vampyronassa rhodanica and 2 extant samples of V. infernalis [the modern-day vampire squid] from the collections at the American Museum of Natural History and the Yale Peabody Museum. We also compared these specimens with other fossils from the literature.

The V. rhodanica fossils were collected from a Lagerstätte in the Ardèche region of France called La Voulte-sur-Rhône. Most lagerstätte preserve fossils as impressions, but at La Voulte-sur-Rhône, specimens are often preserved in 3D.

IE: In the paper, you describe a reanalysis of the fossils using modern techniques. When was the original analysis and what did those investigators find?

Rowe: The initial description of V. rhodanica was by Fischer & Riou in their 2002 paper. At the time of publication, the authors had to rely on observations of the external form for their anatomical descriptions. They were able to describe many external features, and based on this they positioned this species as the oldest likely relative of the modern-day vampire squid (V. infernalis).

IE: What new tools did you use to analyze these fossils two decades later?

Rowe: We chose to reanalyze some of the Vampyronassa rhodanica specimens described in the 2002 paper using powerful X-ray-based imaging techniques at both the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle in Paris and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility Synchrotron (ESRF, ID 19 beamline, Grenoble, France). We used these same X-ray techniques at the American Museum of Natural History on the two modern vampire squid.

Using these data, we were able to identify the boundaries of anatomical structures and reconstruct them in 3D.

IE: What did that analysis reveal?

Rowe: The results were exciting. For example, the kind of resolution we were able to get on the suckers of V. rhodanica was completely unknown before the acquisition of this data. We were able to determine that the sucker attachment of V. rhodanica is the same type seen only in modern V. infernalis, though the overall shape is of the sucker itself and reflects those of octopuses.

IE: What do those findings suggest about V. rhodanica's life and behavior?

Rowe: Though we obviously can’t observe how V. rhodanica used their suckers. By comparing preserved anatomical features with that of coleoids today – suckers and cirri for example – and knowing how they function now, we can infer how the same features may have been used by the Jurassic V. rhodanica. Based on functional comparisons with modern coleoids, the combination of characteristics observed in the arm crown of V. rhodanica, as well as their streamlined, muscular mantle, suggest they were adapted to a pelagic, predatory lifestyle.

IE: Were you surprised? Were your findings consistent with the original analysis?

Rowe: The soft tissues of modern coleoids hold a lot of information about their lifestyle, though this is rarely preserved in fossils. Based on previous work we had a sense of the external characters that had been preserved, though the resolution with which we could see the detail of these tissues in the scans was fantastic.

IE: How do your findings change what experts know about V. rhodanica? Do they offer clues about its broader environment or ecology?

Rowe: The lifestyle of V. rhodanica is in contrast with that of the modern vampire squid. It is unclear when the adaptation to the deep-sea lifestyle occurred in the lineage, though recent work has described a fossil species of this family inhabiting this environment in the Oligocene, around 33.9 to 23 million years ago. The initial shift from shallower to deeper waters was possibly driven by competition in onshore environments. The mosaic of characters found in the coleoid taxa at La Voulte-sur-Rhône (V. rhodanica and other species), suggests that Mesozoic coleoids co-occurred in different ecological niches during the mid-Jurassic.