The lost star catalog of Hipparchus – regarded as the earliest known attempt to map the entire night sky – may have just been discovered on parchment preserved at St Catherine's Monastery on Egypt's Sinai Peninsula.

In 2012, the student of leading biblical scholar Peter Williams noticed something curious behind the lettering of the Christian manuscript he was analyzing at the University of Cambridge.

The student, Jamie Klair, had stumbled across a famous passage in Greek that was often attributed to Eratosthenes; an astronomer and the chief librarian at the Library of Alexandria (one of the most prestigious places of learning in the ancient world).

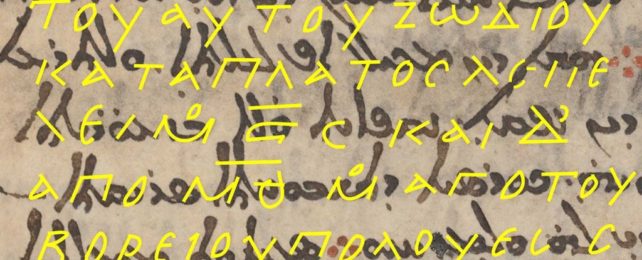

In 2017, multispectral imaging of the document revealed nine folios of pages containing hints of a text that had been written over. It wasn't an unusual finding in itself – parchment was a valuable commodity in centuries gone, so it wasn't uncommon for scholars to scrape old skins for reuse.

Poring over the results in the second year of the pandemic, Williams noticed some odd numbers in the St Catherine's Monastery folios.

When he passed off the page to scientific historians in France, researchers were shocked. Historian Victor Gysembergh from the French national scientific research centre CNRS in Paris told Jo Marchant at Nature that "it was immediately clear we had star coordinates."

So how do we know who these coordinates were written by?

The short answer is we don't – at least not with full certainty. What experts do know, however, is that the Greek astronomer, Hipparchus, was working on a star catalog of the western world's sky between 162 and 127 BCE.

Several historical texts refer to Hipparchus as 'the father of astronomy' and credit him with the discovery of how Earth 'wobbles' on its axis in what's now known as a precession. He's also said to be the first to calculate the motions of the Sun and Moon.

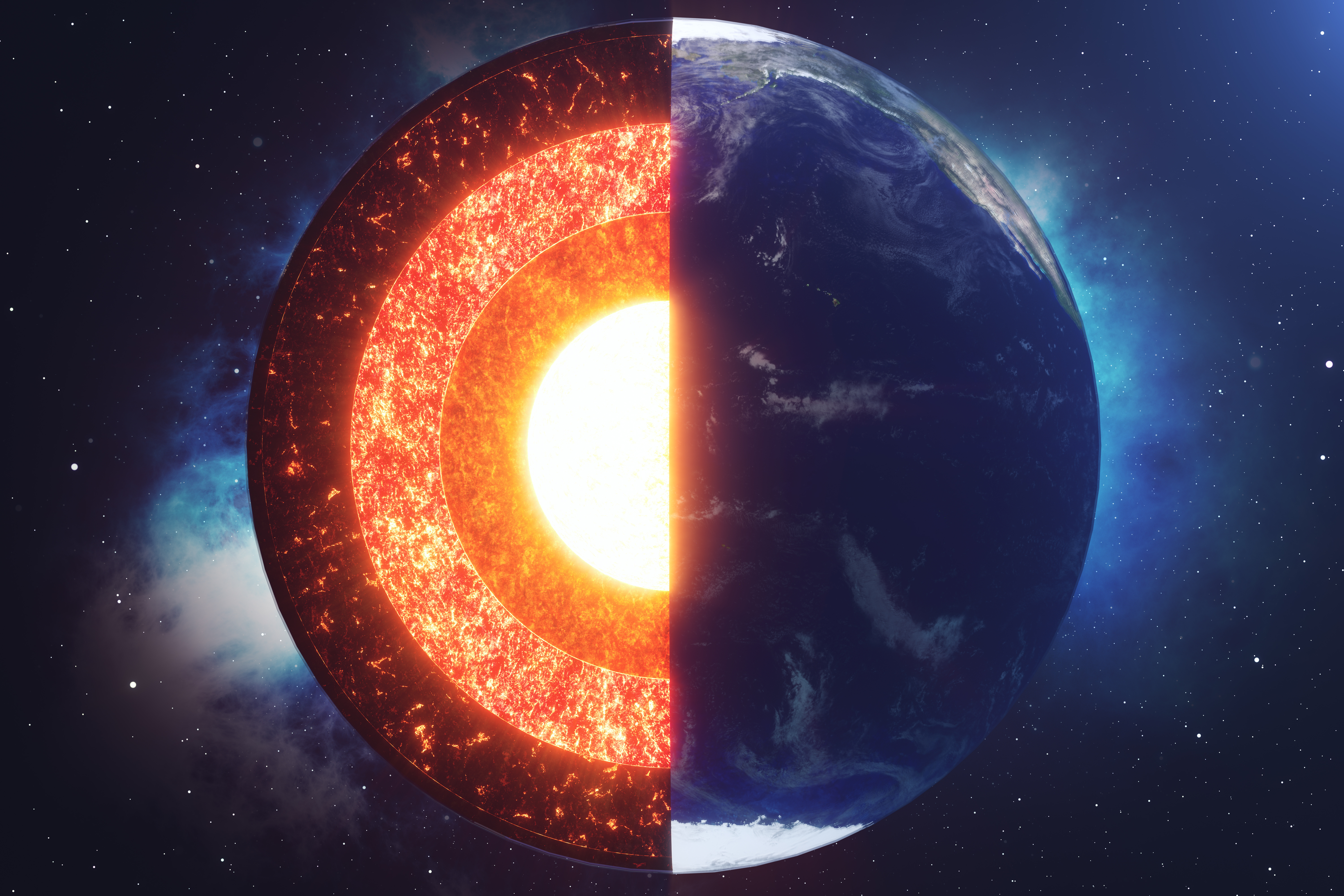

Looking at the star map buried behind the text of the St Catherine's Monastery parchments, researchers worked backwards to figure out Earth's precession at the time the map was written. The coordinates of the stars roughly matched the precession expected of our planet around 129 BCE, within Hipparchus' lifetime.

Until this map was found, the oldest known star catalog was put together by the astronomer Claudius Ptolemy in the second century AD, three centuries after Hipparchus.

The only other work left by Hipparchus is a commentary on an astronomical poem which describes stellar constellations. Many of the coordinates Hipparchus gave to the stars in his Commentary on the Phaenomena closely match the document from St Catherine's Monastery, though the fragmented text can be difficult to decipher.

Legible coordinates of only one constellation, Corona Borealis, can be recovered from the folios from Egypt, but researchers think it is likely that the entire night sky was mapped by Hipparchus at some point.

Without a telescope, such work would have been extremely challenging and time intensive.

According to the researchers, the hidden passage reads as such:

"Corona Borealis, lying in the northern hemisphere, in length spans 9°¼ from the first degree of Scorpius to 10°¼8 in the same zodiacal sign (i.e. in Scorpius). In breadth it spans 6°¾ from 49° from the North Pole to 55°¾.

Within it, the star (β CrB) to the West next to the bright one (α CrB) leads (i.e. is the first to rise), being at Scorpius 0.5°. The fourth9 star (ι CrB) to the East of the bright one (α CrB) is the last (i.e. to rise) [. . .]10 49° from the North Pole. Southernmost (δ CrB) is the third counting from the bright one (α CrB) towards the East, which is 55°¾ from the North Pole."

The notations match ancient Greek terminology. The term 'length' is based on East-West extension of a constellation, while 'breadth' describes the North-South extension of the constellation.

Compared to Ptolemy's later work, Hipparchus' mathematics appear to be much more reliable, within one degree of what modern astronomers would later find. This suggests Ptolemy did not simply copy Hipparchus' work.

Another manuscript, a Latin translation of the Phaenomena from 8th century AD, shares similar structure and terminology to the Corona Borealis passage, which suggests it is also based on Hipparchus' work.

The constellations mapped in this document are Ursa Major, Ursa Minor and Draco. Again, many of the star's values match what is seen in Hipparchus' Commentary.

Some astronomers had previously suggested that Hipparchus wrote the original coordinates that were cited in these Latin documents, but the discovery of this new text adds further weight to that idea.

"The new fragment makes this much, much clearer," Mathieu Ossendrijver, a historian of astronomy at the Free University of Berlin, told Nature.

"This star catalog that has been hovering in the literature as an almost hypothetical thing has become very concrete."

Researchers are hopeful that more legible text can be recovered from the monastery's papers in the future.

The study was published in the Journal for the History of Astronomy.