A restored medieval depiction of the Crusades shows how England embraced Islamic culture

Floor tiles from Chertsey Abbey in England, the subject of a new exhibition, resemble Muslim and Byzantine silks that crusaders brought back as souvenirs.

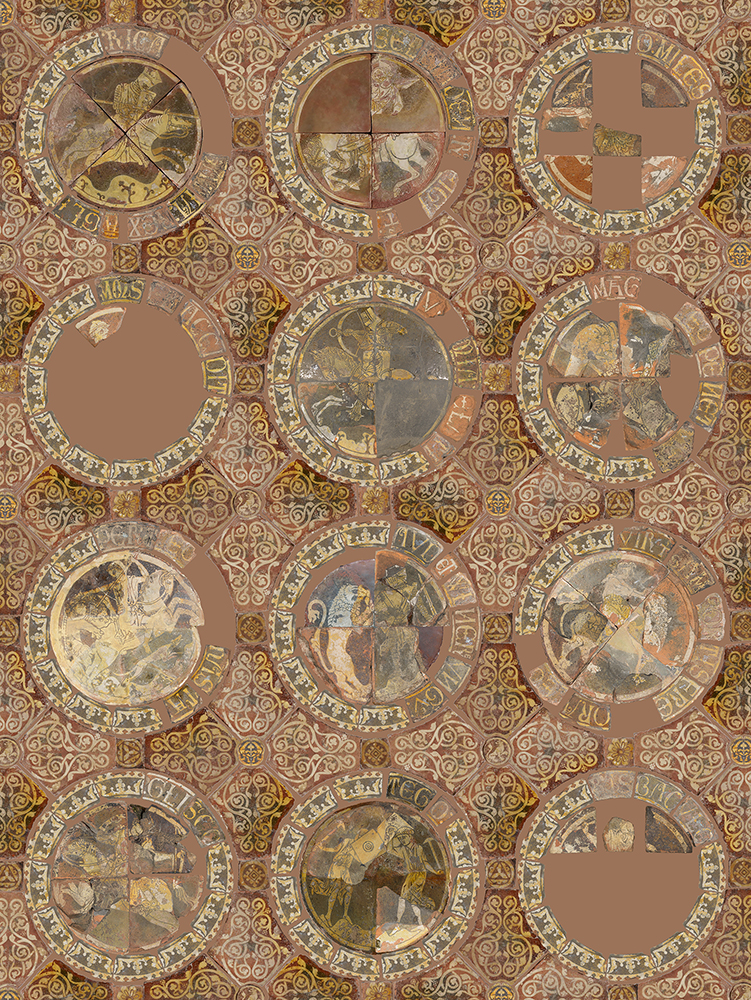

Digital reconstruction of Richard the Lionheart and Saladin and proposed

(RNS) — An 800-year-old puzzle about a set of 13th-century floor tiles has added to historians’ thinking about the relationship of Europeans and Arabs at the time of the Crusades.

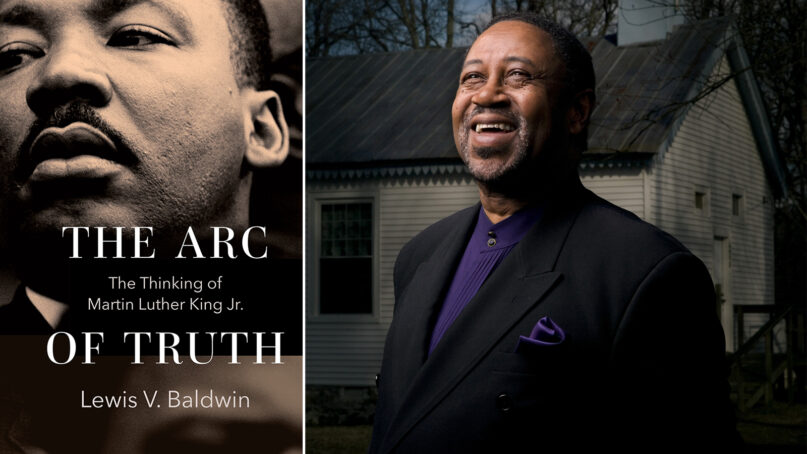

Amanda Luyster, assistant visual arts professor at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, has spent more than two decades studying the so-called combat series, a group of floor tiles uncovered in the 1850s at the ruins of Chertsey Abbey, some 20 miles southwest of London.

Luyster’s research findings underpin the exhibition “Bringing the Holy Land Home: The Crusades, Chertsey Abbey, and the Reconstruction of a Medieval Masterpiece,” which runs Jan. 26 to April 6 at the college’s Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Art Gallery.

The tiles, which were illustrated and annotated with Latin inscriptions, are among the most significant medieval objects of their kind from England, if not all of Europe, according to Luyster. But since the discovery of the highly fragmented tiles, scholars had largely focused on reconstructing the illustrations, which include scenes of Richard the Lionheart battling Saladin in the Third Crusade a half-century before. The Latin text was too badly broken up at the time to be pieced together and read.

Working with colleagues who coded programs to digitally fit the letters together and cross-referenced them against known Latin texts of the era, Luyster assembled about half of the Latin inscriptions to her satisfaction. She also arranged the illustrations as her research suggests they would have appeared on the abbey floor.

Once restored to their original look, the new design reminded her of Muslim and Byzantine silks that Crusaders brought back as souvenirs.

Digital reconstruction of the Chertsey combat tile mosaic pavement. Photographic composite showing roundels surrounded by partial Latin texts. Photo © Janis Desmarais and Amanda Luyster

Luyster has no illusion that the Crusades, waged from 1095 to 1291, were anything less than major confrontations. But she sees the tiles as telling visual evidence that England during the Middle Ages had robust contact with the rest of the world and that Christian Europe was more porous than historians have believed.

Instead, Luyster said, while the tiles depict Europeans clashing with the Muslims who ruled Jerusalem and the Near East, their manufacture and design reflected familiarity with, and admiration for, Arab artistry. They support the idea that far from thinking of themselves as European, the English who went on Crusades and came back to create these tiles were in deep conversation with Arab culture.

“The Crusaders and other Western Europeans see themselves as Westerners becoming Easterners. Their whole identity is changing, as they move and start living in the area around Jerusalem,” Luyster said.

This cultural fluidity is at odds with a picture of medieval English society as isolated, purely Christian and culturally homogeneous — a view that is increasingly outdated among historians of the period, even as white supremacists in England and the United States have latched onto it.

The key to Luyster’s insight are tiles illustrating the English King Richard I, known as Richard the Lionheart, wounding the Muslim ruler Saladin with a lance, and of a Muslim soldier with an arrow piercing his forehead.

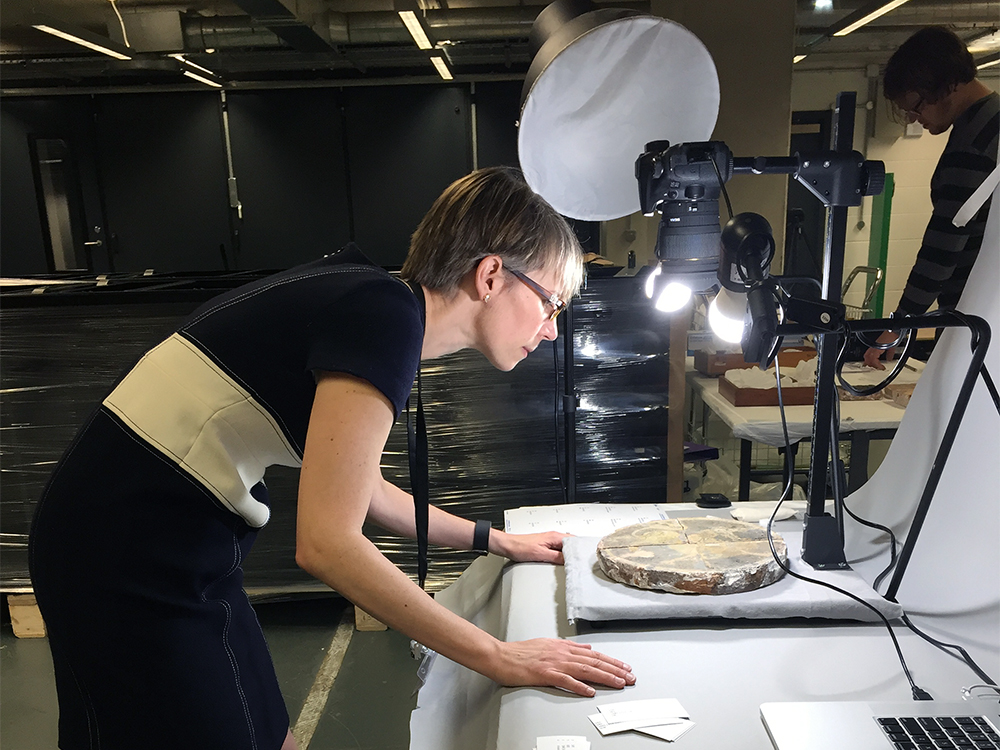

Amanda Luyster at the British Museum photographing the Chertsey tiles in 2017. Courtesy photo

Historians had long known that Richard and Saladin appeared in the overall design of the abbey’s tiles, but other tiles were thought to represent other battles. Luyster’s high-tech detective work on the Latin inscriptions showed, she concluded, that the entire design, not just the Richard and Saladin illustrations, depicted the Third Crusade, led by Richard.

That Crusade had ended in a draw, however, and Richard had never met Saladin on the battlefield, much less speared his foe. The rewrite suggested to Luyster that the tiles were not a faithful history, but rather propaganda generated by King Henry III and his queen, Eleanor, aimed at pumping up Christians for another Crusade. Portraying Richard slaying Saladin in a victory for Christendom would help them carry out their plan.

“This commission of the floor is their way of drumming up attention to the idea that another English Crusade could be successful like the last one was, apparently,” Luyster said.

But the very propaganda meant to excite would-be Crusaders borrowed its form from Muslims, Luyster said. This borrowing, and the fact that church inventories of the period in England and elsewhere included Islamic textiles, known as Saracen cloth, used even as vestments for Mass, shows how highly English Christians valued Arab culture, according to Luyster.

“While there’s all this discourse about how awful Muslims are in written and political arenas, in visual culture something else is going on. There’s a generalized feeling that English and other Crusaders can hate the people, but love the stuff,” Luyster said.

“But then we think, ‘If you love the stuff, your hatred of the people must also include some kind of strand of respect, even if you don’t admit that truth,’” she said.

Two historians of the Crusades who were not involved with the exhibition agreed that the Crusades were much more complicated than a clash between East and West.

Researchers at the British Museum discuss the Chertsey tiles in 2017. Courtesy photo

“It’s pretty well established now in the mainstream of medieval studies that Western Europe, including England, was plugged into a much wider, cosmopolitan world of trade, cultural contacts and exchanges,” said Brett Whalen of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Violence between Christians and Muslims in the Middle Ages was “only one small part — maybe not the most important part — of a much bigger picture, as evident in objects like the Chertsey tiles,” he added. “The reductionistic ‘clash of civilizations’ model is a relic of 1990s thinking in the aftermath of the Cold War and tells us little to nothing about the medieval world.”

What’s more telling than illustrations of Christian-Muslim violence, said Christopher Tyerman, professor of the history of the Crusades at Oxford’s Hertford College, was the “greater contact between an increasingly prosperous Western Europe and the wealthier — in all senses — culture and economies of Byzantium and the Near East.”

Cultural and commercial exchange accelerated at the time. “The construct of an eternal ‘clash of civilizations’ is historically just plain wrong and also conceptually muddled,” Tyerman said. That construct is “concocted by conservative zealots of all persuasions and faiths to justify (and) explain unrelated coincidental modern conflicts.”

Christians and Muslims often fought with co-religionists, and both crossed religious lines, allying with those of other faiths. And Christians and Muslims did business together during the Crusades.

“Trade knows no religion,” he said.