Making sweat feel spiritual didn’t start with SoulCycle – a religion scholar explains

Fitness and religion make a potent combination, one people have explored for centuries.

(The Conversation) — Each January, Americans collectively atone for yet another celebratory season of indulgence. Some proclaim sobriety for “Dry January.” Others use the dawn of a new year to focus on other forms of self-improvement, like taking up meditation or a new skin care routine. But adopting a new fitness plan is the most popular vow.

Fitness experts insist that the best kind of exercise is the one you will do regularly – the one you can view as a joy, not a chore. And as more and more bespoke boutique fitness programs pop up, some devotees seem to take this advice even further. The notion that fitness is a religion – a place where people find community, ritual and ecstatic experience – has become a common refrain.

Can fitness really be a religion? Given the difficulty of defining religion, it’s an almost impossible question to answer. Is religion about belonging? Transcendence? Feeling the divine? Is it scripture, traditions or creeds? Religions can have all of these traits, or none of them.

Perhaps the better questions to ask are why fitness and religion make such a potent combination, or why people see fitness as religious – ideas I explore in my research on CrossFit and SoulCycle.

Working out with God

There is ample evidence of fitness trainers, influencers and companies unabashedly incorporating religious language, sentiments and practices into their exercise routines.

Take Peloton’s superstar cycling instructor Ally Love. A former theology student, Love offered sermonlike messages on topics such as accountability and selflessness, and occasionally played music from Christian artists during her weekly “Sundays with Love” rides, prompting some riders to argue that Peloton should label her content as Christian.

Then there are explicitly faith-based programs using fitness to enhance religious practice. The Catholic workout SoulCore integrates prayers of the rosary with core exercises, stretches and functional fitness movements to “draw others closer to Christ.” A “Neshama Body & Soul” class offered by a Conservative Jewish synagogue in Saratoga, California, meanwhile, combines prayers with jumping jacks, planks and lunges.

Religion, remixed

More common than traditionally religious fitness programs, though, are ones that borrow the trappings of religion and more subtly tap into spiritual experience.

SoulCycle, another iconic indoor cycling program, makes regular use of religious aesthetics, ritual and language in its classes. Instructors may talk about the cosmic energy radiating from the class or guide riders through opening their spiritual centers, or chakras. In candlelit rooms, instructors praise strong efforts by presenting selected riders a candle to blow out during the “soulful moment” of class. This soulful moment comes at the end of the 45-minute class arc, designed to deliver a breakthrough moment of spiritual or personal revelation and catharsis by combining the natural high of physical intensity with spiritualized self-help messaging.

An Equinox fitness center in Brooklyn, New York.

Angela Weiss /AFP via Getty Images

Other fitness trends, like CrossFit and the meetup group November Project, are less intentional about incorporating religious messaging. However, they’ve garnered reputations for being religious or cultish because of how intensely they foster community. Special jargon – like “WOD,” which stands for workout of the day – as well as annual activities and special commemorations like “hero workouts,” which honor people killed in the line of duty, solidify the religious comparisons.

CrossFit, in particular, has also attracted overtly Christian exercisers, with some of its most famous athletes publicly professing their faith.

Centuries of connection

To understand the relationship between fitness and religion, it helps to look at their history.

First, fitness itself is a relatively new concept. While there are certainly ancient accounts of sport and military training, the idea that one ought to exercise for health, enjoyment and community is a modern invention, a response to increasingly sedentary jobs and cultures.

But while voluntary exercise is new, intense physical regimens to connect with the divine are not. People have long experimented with ways to generate a sense of transcendence, to stir emotions, or to spur self-reflection through bodily discipline. The Siddhas, mystics in ancient India, developed unique physical practices in an attempt to achieve enlightenment, render the body divine and, ultimately, become immortal beings. Or consider 12th century Taoist ascetics who thought sleep deprivation could bring them closer to the truth. Catholic saints practiced self-mortification, such as wearing itchy sackcloth, to encourage humility and to create greater compassion for the suffering of others.

Religious fixations with the body highlight an abiding paradox: Many faiths view the body as a temple, but also a hazard to the soul. They teach that the body must be disciplined and tamed, yet honored as a conduit to the divine.

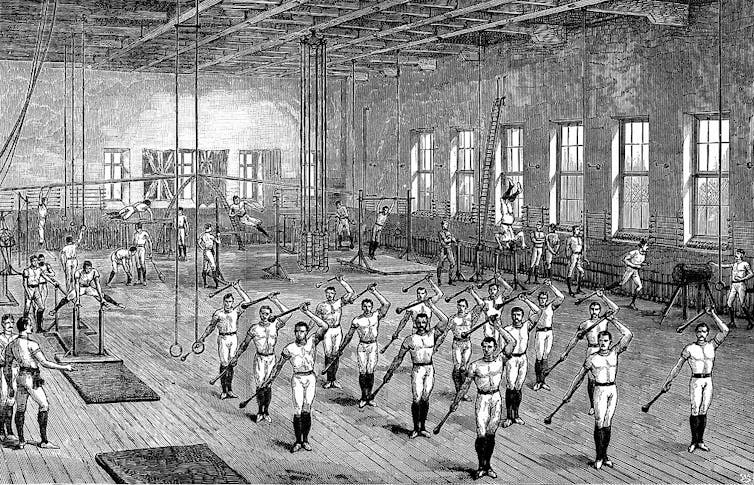

Training the body to move the soul along a path toward salvation did not disappear with modernization. Rather, movements like “muscular Christianity” arose at the turn of the 20th century, blending fitness and bodybuilding techniques with Christian piety. The YMCA, for example, opened gyms to train physical and moral strength in young Christian men. As religion scholar Marie Griffith writes, such movements reinforced a message that “fit bodies ostensibly signify fitter souls.”

Wooden engraving of a Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) gymnasium opened in London in 1888.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Evangelical sports ministries took off later in the 1950s, followed by the U.S. yoga boom in the late 20th century. Together, these developments underscored the enduring connection between flesh and spirit, and primed 21st century exercisers to readily accept spirituality as part and parcel of their fitness routines.

Shopping for fulfillment

This history is important, yet it is incomplete. Most journalists and cultural analysts who write about fitness as religion also cite the decline of traditional religious belonging as the reason people are finding spiritual fulfillment in other settings. People’s religious needs have not disappeared, they argue, rather they appear remixed and re-bundled for the modern secular consumer.

Fitness entrepreneurs use this explanation, as well.

“That stuff that happened on Sunday morning at church or in your synagogue is still important to human beings,” John Foley, founder and CEO of Peloton, stated in a 2017 talk. People want “candles on the altar and somebody talking to you from a pulpit for 45 minutes – the parallels are uncanny. In the ’70s or ’80s, you’d have a cross or Star of David around your neck. Now you have a SoulCycle tank top. That’s your identity, that’s your community, that’s your religion.”

As Foley’s quote highlights, the market is not only responding to people’s desire for ritual, guidance, spirituality, reflection – and even a sense of salvation. Rather, companies are also feeding into those desires, and helping to generate them.

Religious objects and experiences have long been available for purchase, but boutique fitness trends show today’s market logic at work: the idea that if you have a personal, spiritual need, there must be a product out there for it. Various seemingly secular companies have attempted to sell spiritual fulfillment, but few have been as successful as for-profit fitness companies that can capitalize on the long history of pairing the status of the body with the status of the soul.

The next time you hear a friend assert that fitness is their new religion, know that it might not be just hyperbole. Rather, it reflects how religious meanings attached to the body have endured, transformed – and are now available for purchase at the nearest fitness studio.

(Cody Musselman, Postdoctoral Research Associate, John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics, Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)