COMMON GROUND

Design | Rubin D’Souza

Section 375 of the Indian Penal Code deals with the crime of rape. It lists seven circumstances under which sexual intercourse is categorised as rape, such as when a man does not gain a woman’s consent, or he gains it through threat of violence. Those convicted under the law are punished with a prison term of at least 10 years, which can be extended to a life sentence, along with a possible fine.

After listing these circumstances, the law notes two “exceptions”. The first refers to medical procedures, which it excludes from the definition of rape. The second states: “Sexual intercourse by a man with his own wife, the wife not being under fifteen years of age, is not rape.”

This is known in Indian law as the marital rape exception. In effect, it protects a married man from being charged under the rape law. While the law originally shielded a man if his wife was under 15, in 2017, the Supreme Court revised that age to 18.

Next month, the Supreme Court of India is due to hear a batch of petitions that ask that the exception be struck down so that marital rape will be categorised as a criminal offence.

Those who defend the exception argue that striking it down will lead to widespread misuse of the law, and break down the traditional institution of marriage.

But activists and lawyers on the ground have a far more pragmatic point of view. Based on their experiences of working with women who have suffered violence from their husbands, including rape, they note that it is still a formidable task for most married women to seek protection from the law against violent husbands, let alone misuse laws. Striking the exception down, they argue, would be a step towards ensuring their safety and empowerment.

This story is part of Common Ground, our in-depth and investigative reporting project. Sign up here to get a fresh story in your inbox every Wednesday.

On May 10, I met with staff of the “Prevention of Violence against Women and Children” programme at the Society for Nutrition, Education and Health Action, or SNEHA, in Dharavi, Mumbai. SNEHA currently runs 12 counselling centres in Mumbai and Thane for women facing gender-based violence. In 1999, the programme began by dealing with domestic violence, since it was the primary form of violence faced by women who approached the organisation. But it soon expanded to address other forms of gender-based violence, such as sexual harassment and violence between unmarried partners. Even today, the majority of the complaints they receive are of domestic violence.

I requested several lawyers and social workers for help in facilitating conversations with married women who had faced sexual violence from their husbands, and sought justice under the law. Understandably, they declined my request, explaining that the question of privacy was paramount, as was ensuring that there was no risk of the women being retraumatised.

But data that SNEHA shared with me was revealing of just how commonplace marital rape is.

Between April 2022 and March 2023, a total of 3,878 cases of gender-based violence were registered with them. Among these, 52.11% of women reported facing some form of sexual violence from their husbands, and 19.33% specifically reported having been raped by their husbands.

Married women currently facing sexual violence in India have two recourses to justice. The first is Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code, which criminalises subjecting a woman to “cruelty”. Under the law, offenders face a maximum punishment of three years and a possible fine.

The second law that a woman subjected to sexual violence can seek protection under is the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005. This civil law lays down rules for the protection of women, along with stipulations on monetary relief in cases where they face violence, and on child custody in cases of disputes. It does not prescribe any punishments for perpetrators of violence – rather, it only prescribes imprisonment of up to one year and a fine in cases where an abuser violates a protection order passed by a court under the law.

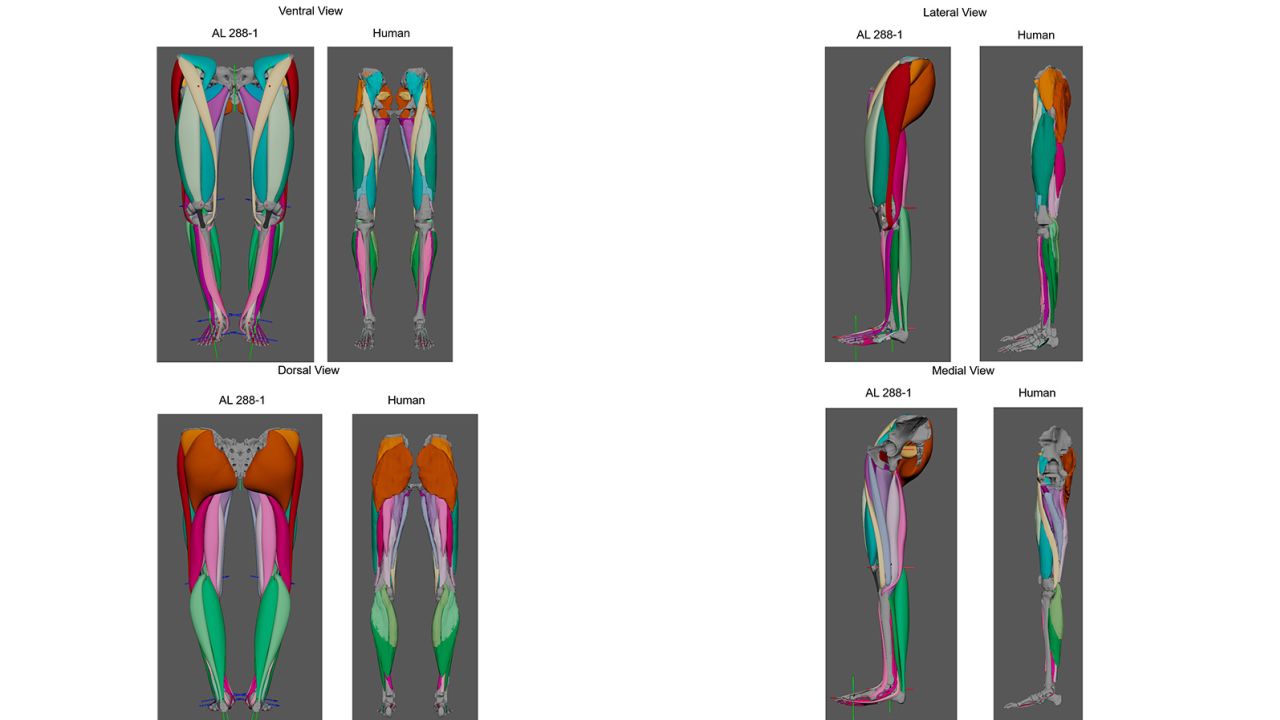

Married women who face violence from their husbands can currently seek recourse under two laws: Section 498A of the IPC, and the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Activists pointed out that even under existing laws, it is a challenge to ensure that women are comfortable enough to speak up about the sexual violence they face. “Talk of violence usually begins with physical violence and other forms,” said Reshma Jagtap, a lawyer and programme coordinator of SNEHA’s prevention of violence programme. “Women first say things like, he denies me food, or he hits me.”

Nikhat Shaikh, director of the programme, noted that sexual violence comes up “only after three-four sittings with the counsellor”.

Typically, it is only when sexual violence is so severe that women have to seek medical aid that they bring it up, Shaikh explained. “For example, we’ve had cases where women have had vegetables inserted into their vaginas,” she said. “So it’s in extreme cases, when their health is at risk, that women open up and report.”

Aileen Marques, a lawyer at the Mumbai High Court, who has worked extensively on cases involving domestic violence, echoed this observation. “Women are vocal about the physical abuse,” she said. “Emotional, verbal, economic comes later. And for sexual violence, we have to keep asking them and make them comfortable with the idea that something like this exists and you need to talk about it. There is a lot of reluctance to talk about the details.”

Sangeeta Rege, director of the Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes, or CEHAT, explained that women are typically subject to different types of violence, which overlap with each other. “Marital rape does not exist in a vacuum,” she said. “It’s usually a combination of physical, emotional and financial violence.”

Programme staff at SNEHA noted that most women were not acquainted with the vocabulary of sexual violence or marital rape. Sheikh said that it was usually only after a few sessions that women began articulating the problem, saying things like, “He is forceful with me, he does it when I’m not in the mood, or he does things which I don’t like, he makes me do it in front of the kids etc.”

The lack of vocabulary can at times also mean a difficulty in understanding what constitutes sexual violence. For instance, Marques had a case of a woman at a senior position in a corporation, who for many years didn’t realise that her husband was subjecting her to sexual violence. It was only after an orientation session at her office on the sexual harassment law she that she realised she was facing sexual violence at home.

This lack of awareness is exacerbated by the misogynist beliefs of men in relationships and marriages. “Often, men have no concept of satisfying their partners, their focus is just on themselves,” Jagtap said. “A very common belief is: the woman is my property. They say things like, ‘If you can’t abide by my fantasies, then why were you brought here?’”

Vandana Singh, Reshma Jagtap, Nikhat Shaikh and Supriya Koli work with the NGO SNEHA in Mumbai, which runs a programme focused on preventing violence against women and children. Photo: Nolina Minj

Social mores also condition women to submit to their husbands. “Women think: won’t people judge me and think I’m not a good wife?” Shaikh said. “Many women carry these justifications in their head and put the blame on themselves.”

Vandana Singh, a programme coordinator at SNEHA, noted that these pressures also come from other members of the family. “You’ll have the mother-in-law saying, ‘It’s your work to keep him happy, if you don’t satisfy him, won’t he force you?’” Singh said.

Changing the mindsets of both men and women is a huge challenge because of the generally poor awareness about sex, sexual health and rights in the country.

“It is not just women’s perception,” Shaikh said. “It’s also the exposure our boys and men get.” She explained that SNEHA’s work with adolescents showed that youth obtained information about sex and sexuality from questionable sources like internet porn and Bollywood movies. “How true is this information, how much should we believe it, its source, all this is not questioned,” she said. “So the right information is not given at the right time, but sexuality still develops and it’s only explored in their married lives.”

Jagtap explained that problematic popular entertainment, like Bollywood movies and television serials, propagated ideas such as that a man must have sex with his wife on their wedding night, and that he had to ensure that the woman’s hymen ruptured and stained the bedsheets. Such expectations prevent mutually respectful and egalitarian relationships from developing, she said.

“Changes in law won’t make much difference until awareness and education occurs,” said feminist social worker Taranga Sriraman.

SNEHA’s findings on the prevalence of marital rape is echoed in data from other organisations and studies.

In 2019, a UN Women report on the status of women worldwide stated that “statistically, the home is one of the most dangerous places for women.” It noted that in 2018, one in five women across the world aged between 15 and 49 had experienced intimate partner violence from a former or current partner or spouse.

In India, according to the latest National Family Health Survey data, collected between 2019 and 2021, 29.3% of women ever married between the ages of 18 and 49 have experienced spousal violence that is sexual, or otherwise physical, or both.

Sangeeta Rege said that though the NFHS data provided some insights, there was a dire need to consolidate data on sexual violence by civil society organisations in the country. “There is no comprehensive mechanism in the country that records data on sexual violence faced by married women,” Rege said. “The NCRB only covers reported crimes, and most instances of sexual violence go unreported.”

In 2022, CEHAT published a study based on service records of counsellors for women seeking support against gender-based violence in hospitals in a city, which it left unnamed to safeguard women’s privacy. It found that between 2008 and 2017, out of 1,783 formerly or currently married women, 68% reported forced penile penetrative sex and 8% reported forced anal or oral penetration.

Lawyers and social workers said that despite the wide prevalence of such sexual violence, the criminal justice system often fails to take cognisance of it.

Advocate Aileen Marques said that when taking up complaints under the domestic violence act, medical workers and law enforcement officers tended to look for signs of external physical violence. “Sexual violence is generally ignored,” she said.

She added that under the domestic violence act, these protection officers “have to compulsorily ask about sexual violence, but in many cases they don’t.”

Though feminist lawyers and activists have struggled for years to make the criminal justice system more accessible to women facing violence, many government staffers still don’t take domestic violence seriously. Citing experiences in Delhi and Tamil Nadu, lawyer Priya Krishnamurti noted that when they encounter complaints of domestic violence, rather than register them formally, often family lawyers and police compel women to undergo negotiations to informally resolve the problems with their husbands or in-laws.

The CEHAT study noted that hospitals and police “respond inadequately to women reporting marital rape, as the rape law exempts rape by husband.”

Several feminist lawyers and social workers that Scroll spoke with said that women underreport sexual violence in marriages. “Women are not reporting sexual violence because they are made to feel they have to live with this violence,” said advocate Ujwala Kadrekar, who practices in the Bombay High Court. She added, “There is stigma and there are consequences.” A commonly feared one, she said, was retaliation from husbands and in-laws.

One of the most prominent arguments against the criminalisation of marital rape is that it will lead to a rise in the number of false cases and husbands in prison.

The news portal Article 14 has reported on how men’s rights groups are steadily mushrooming in India – after a group of activist organisations, along with some individuals filed petitions in the Delhi High Court in 2015, asking that the marital rape exception be struck down, two such men’s rights groups submitted petitions against the striking down of the exception.

Purveyors of arguments in favour of the exception hold that women abuse laws, and that the legal system is rigged against men. As evidence of this, they cite high acquittal rates of cases filed under Section 498A of the IPC, which deals with cruelty towards a married woman. According to the latest NCRB data, in 2021, of a total of 7,65,709 such cases at the trial stage, only 36,421 cases, or 4.7%, were disposed of while 7,29,288, or 95.2%, remained pending. Of the cases that were disposed of, 4,315, or 11.8%, resulted in convictions, while 19,851, or 54.5%, resulted in acquittals.

But feminist scholars have disputed such arguments, and allegations that women are widely misusing section 498A. A paper examining cases of 498A that were disposed of after police investigations stated that first, “women faced significant physical and mental violence before taking the decision to file a case under Section 498A”. Later, the paper noted, a case would typically be “labelled as ‘false’ at the time of closure, because the police had effected a negotiation with the perpetrator, and the only avenue to legally close a case at this stage (because this offence is non-compoundable) is to register it as ‘false’ or as a ‘mistake of fact’.”

Among the common arguments made by those who oppose the criminalisation of marital rape is that it will lead to a rise in false cases against men. Activists have refuted this argument.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons/Hemant Shesh

Similarly, in another paper, advocate Shalu Nigam explained that domestic violence was generally seen as a lesser crime by the criminal justice system, and that there existed “tremendous pressure on women to reconcile or settle” cases. Citing data from multiple studies, she wrote, “far from being misused, the provisions under Section 498A remain underutilized.”

Advocate Ujwala Kadrekar said that low conviction rates were also a result of a lack of evidence.

“This violence is happening behind four walls, there’s nobody to support or substantiate her claim that she’s been violated,” said Kadrekar. She added that in many cases family members would also refuse to depose on behalf of the women.

Data from SNEHA indicated that women do not generally favour pursuing criminal prosecution. Between April 2022 and March 2023, only 15% of women facing domestic violence who approached the organisation sought legal redress against their husbands.

“In our experience, women want to go back, they don’t want to fight a legal battle,” Shaikh said. “They know that if they go to the court, they don’t have money for it.” She added, “Even if we use free services like the District Legal Services Authority, when will the case stand for trial? Matters often get settled in counselling sessions.”

Kadrekar, who helped draft the civil Protection from Women against Domestic Violence Act, explained that that law was designed with a focus on protective measures rather than punishment, specifically keeping in mind women’s reluctance to seek punishment for their husbands. “We were very sure that the majority of women don’t want their husbands to be behind bars. They just want the violence to stop,” said Kadrekar. The law, she said, was thus drafted to tackle the question: “How do we correct this wrong behaviour of the husband?”

Yet, the Central government’s submissions in the Delhi High Court in 2017 echoed the view that Section 498A was being misused, and that criminalisation of marital rape could become “an easy tool for harassing husbands”. In 2022, it reiterated its stance to the Delhi High Court saying that criminalisation “could open floodgates of false cases being made with ulterior motives.”

Politicians have also repeated similar melodramatic views. In 2022, when asked about the government’s stance on marital rape, Minister for Women and Child Development Smriti Irani said it wasn’t advisable “to condemn every marriage in this country as a violent marriage, and to condemn every man in this country as a rapist.” Likewise, Bharatiya Janata Party member of parliament Sushil Modi said that criminalising marital rape would “end the institution of marriage” and that “it would not be possible to ascertain when the wife consented to sexual intercourse, and when she withdrew the consent.”

In 2022, when asked about the government’s stance on marital rape, Minister for Women and Child Development Smriti Irani said it “wasn’t advisable to condemn every man in this country as a rapist.”

Photo: Wikimedia Commons/World Trade Organization

But experts point out that in a country where even women complaining against physical violence fail to get support from the police, those experiencing sexual violence have stronger reasons to stay silent. For instance, they may fear for their families’ welfare.

As a typical example, Kadrekar spoke of a case where a woman who was facing severe sexual violence from her husband, and who was admitted to the hospital for treatment, did not cooperate with the investigation because she had young children whose lives, she worried, would be disrupted by any investigation. “Unless a woman has holistic support, it is very difficult to go ahead with such cases,” Kadrekar said. “The children were definitely her priority, but it came at the cost of negotiating with a violent situation.”

Jagtap mentioned a similar case, where a woman who was estranged from her husband was brutally sexually assaulted by him during the lockdown. However, when the wife spoke of taking legal action, the husband, who lived with their daughter, said that he couldn’t afford a lawyer to fight the case, and warned her that he would stop sending her daughter to school. “So she let it go and decided to give him a second chance,” Jagtap said. “Imagine, she didn’t have any other avenue, so she had to compromise.”

Even in cases that don’t involve children, women or their families may avoid filing cases as a result of practical considerations.

Jagtap recounted another case, where a married woman faced such brutal sexual violence from her husband that she was left paralysed. And yet, her natal family was uninterested in filing any charges against the husband. Their primary concern, instead, was to obtain adequate compensation to be able to take care of the woman.

In instances where women opt to prosecute their husbands, the trials take years to even begin – as a result, women often withdraw their cases.

“By the time the case comes for trial, the woman’s life takes a U-turn,” Shaikh said. “She has to relive that traumatic experience again. Women don’t have the time to run around courts, so they compromise.”

In one such case, which was filed in 2012, and whose trial only started in 2019, Jagtap said that the woman complainant had moved on with her life in the seven intervening years, and so decided not to go ahead with the case. “There was forceful sex, anal sex and sexual advances from the marital family,” Jagtap said. “Despite this, she didn’t want to go to the court and speak of these things again. We had to give her therapy because when she recalled all this she went into depression.”

Kadrekar said, “The system really fails women seeking justice.”

In light of these immense hurdles women face in filing cases, experts explained that striking down the marital exception to rape laws would not lead to a rise in the misuse of the laws. “When you talk of misuse, you’ll find that any law can be misused,” Shaikh said. “Why don’t we talk about the misuse of anti-theft laws? Why do we see this only with domestic violence?”

Rege argued that the idea that a large number of women will start litigating if the exception is struck down “is absolutely baseless”.

In fact, she said, if the exception were struck down, it would not necessarily bring about significant changes on the ground at all – nevertheless, it would still be a symbolic and ideological victory for women’s rights in India. “For law enforcement and the health system to take it seriously, it must be made into an offence,” Rege said. “We are in 2022, why does this exception still exist? Why does the country still deny a human right to married women?”

The legal battle that began in the Delhi High Court in 2015 ended in May 2022, in a split verdict.

In his judgment, Justice Rajiv Shakdher, who was in favour of criminalising marital rape, wrote: “What looms before us is Lord Hale’s Ghost. Thus, the key question which arises for consideration in these matters is whether or not we should exorcize Hale’s Ghost?”

This was a reference to the British jurist Matthew Hale, who in a 1736 treatise, wrote the oft-quoted defense against the criminalisation of marital rape. At the time, there was no specific law that granted husbands immunity from charges of raping their wives – rather, judges developed a common law case by case. (Common law refers to law that is not enacted by a legislature, but emerges out of the judgments of courts.)

Examining the question, Hale wrote, “the husband cannot be guilty of a rape committed by himself upon his lawful wife, for by their mutual matrimonial consent and contract: the wife has given up herself in this kind unto her husband, which she cannot retract.”

This line of thought was drawn from the doctrine of coverture, under which when a woman married, her legal existence was merged with her husband’s; in effect, she then ceased to be an independent legal entity.

Hale’s reasoning proved hugely influential in the decades to come, and was quoted in several judgments that upheld the marital rape exception.

https://www.propublica.org/article/abortion-roe-wade-alito-scotus-hale

May 6, 2022 ... Justice Alito's leaked opinion cites Sir Matthew Hale, a 17th-century jurist who conceived the notion that husbands can't be prosecuted for ...

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/05/09/alito-roe-sir-matthew-hale-misogynist

May 9, 2022 ... Most Americans have probably never heard of Hale, an English judge and lawyer who lived from 1609 to 1676. Hale was on the bench so long ago ...

https://www.bostonglobe.com/2022/05/06/metro/who-was-matthew-hale-17th-century-jurist-alito-invokes-his-draft-overturning-roe

May 6, 2022 ... Wade, Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito leans heavily on the scholarship of 17th-century English judge Sir Matthew Hale to underpin his ...

A treatise by the 18th-century British jurist Matthew Hale, in which he argued that a husband could not be held guilty of raping his wife, was hugely influential in the years to come. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Scholars have noted that this perspective was also adopted by several British colonies and codified into law. In 1991, England itself outlawed the marital rape exception. But it remained in Indian law, despite decades of arguments against it by feminist activists.

After the massive protests following the 2012 Delhi rape case, the Justice Verma Committee report recommended substantive changes in laws on sexual offences under the Indian Penal Code. On the question of marital rape, the report said, “The exemption for marital rape stems from a long outdated notion of marriage which regarded wives as no more than the property of their husbands.” It argued that the law should specify that a marital relationship between a complainant and accused was “not a valid defence” against an accusation of rape.

However, in early March 2013, the Department-Related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Home Affairs examined the proposals of this report and brought out its own report. It stated that certain members believed that criminalising marital rape had “the potential of destroying the institution of marriage.” It noted, “if the marital rape is brought under the law, the entire family system will be under great stress and the Committee may perhaps be doing more injustice.” Eventually, the recommendations were not adopted when the IPC was amended.

Since then, there have been multiple instances in which the exception has been defended.

In February 2015, for instance, the Supreme Court rejected a plea filed by a married woman to criminalise marital rape saying “the law couldn’t change for one person”.

In April that year, in reply to Member of Parliament Kanimozhi’s question on whether a bill would be passed to remove the exception, the then minister of state for home, Haribhai Parthibhai Chaudhary said, “It is considered that the concept of marital rape, as understood internationally, cannot be suitably applied in the Indian context due to various factors e.g. level of education/illiteracy, poverty, myriad social customs and values, religious beliefs, mindset of the society to treat the marriage as a sacrament, etc.”

Nonetheless, in March 2022 the Karnataka High Court ruled that a married man can be prosecuted for raping his wife. The judgment was delivered in the case of Hrishikesh Sahoo vs State of Karnataka, in which a woman accused her husband of several brutal sexual offences, including raping her and sexually abusing their daughter. Hrishikesh Sahoo, the defendant, filed a petition in the high court, invoking the marital rape exception, and asking for the charges of rape to be dropped. In its judgment, the court rejected the plea, relying on the recommendations of the Verma committee report while laying out its reasoning.

Sahoo then moved the Supreme Court, challenging this decision – in July 2022, a three-judge bench issued an interim stay on the high court’s judgment. No further hearings have been held in this matter yet.

In parallel, the Delhi High Court delivered its split verdict of May 2022, which remains the prevailing judicial ruling on the question. In his judgment, Justice Rajiv Shakdher ruled that the exception violated several articles of the Indian Constitution, which guarantees equality to all citizens.

He stated, “a married woman’s right to bring the offending husband to justice needs to be recognized. This door needs to be unlocked; the rest can follow. As a society, we have remained somnolent for far too long.”

He further wrote, “It would be tragic if a married woman’s call for justice is not heard even after 162 years, since the enactment of IPC. To my mind, self-assured and good men have nothing to fear if this change is sustained.”

In contrast, Justice C Hari Shankar held the exception was not unconstitutional, but rather, was based on intelligible differentia – specifically, the difference in a relationship between a married man and woman, and couples in other types of relationships. Within marriage, he wrote, there is a “legitimate expectation of sex.” In his 200-page long judgement, he argued that, “Introducing, into the marital relationship, the possibility of the husband being regarded as the wife’s rapist, if he has, on one or more occasion, sex with her without her consent would, in my view, be completely antithetical to the very institution of marriage, as understood in this country, both in fact and in law.” He also stated, “Protection of the institution of marriage is, therefore, a sanctified constitutional and social goal.”

After this split verdict, petitioners moved the Supreme Court, which in January this year clubbed together for hearing, all petitions pertaining to the marital rape exception, including Sahoo’s.

Hearings are slated to begin in July. So far, the Supreme Court has given some indication that it does not side with Justice Shankar’s views. In September 2022, in a separate case pertaining to an unmarried woman’s rights to seek medical termination of a pregnancy, Justice Chandrachud observed, “A woman may become pregnant as a result of non-consensual sexual intercourse performed upon her by her husband. We would be remiss in not recognising that intimate partner violence is a reality and can take the form of rape.”

The upcoming hearing will be an important milestone for women’s rights in the country. Jagmati Sangwan, vice president of the All India Democratic Women’s Association, which is one of the petitioners challenging the exception, said, “It is under the guise of our culture and traditions that violence against women, especially domestic violence including marital rape is invisibilised. And women are forced to pay the price of this in their intimate lives.”

She noted that “all civilised societies and countries which are sensitive to women” had categorised marital rape a crime. “But our government is patriarchal and casteist, they view any discussion on the subject of marriage to be a crime,” she added. “About 80% of the violence that women face is domestic violence. This is why such offenses have to be recognised as crimes and controlled.”

This reporting is made possible with support from Report for the World, an initiative of The GroundTruth Project.