Businessweek

The Big Take

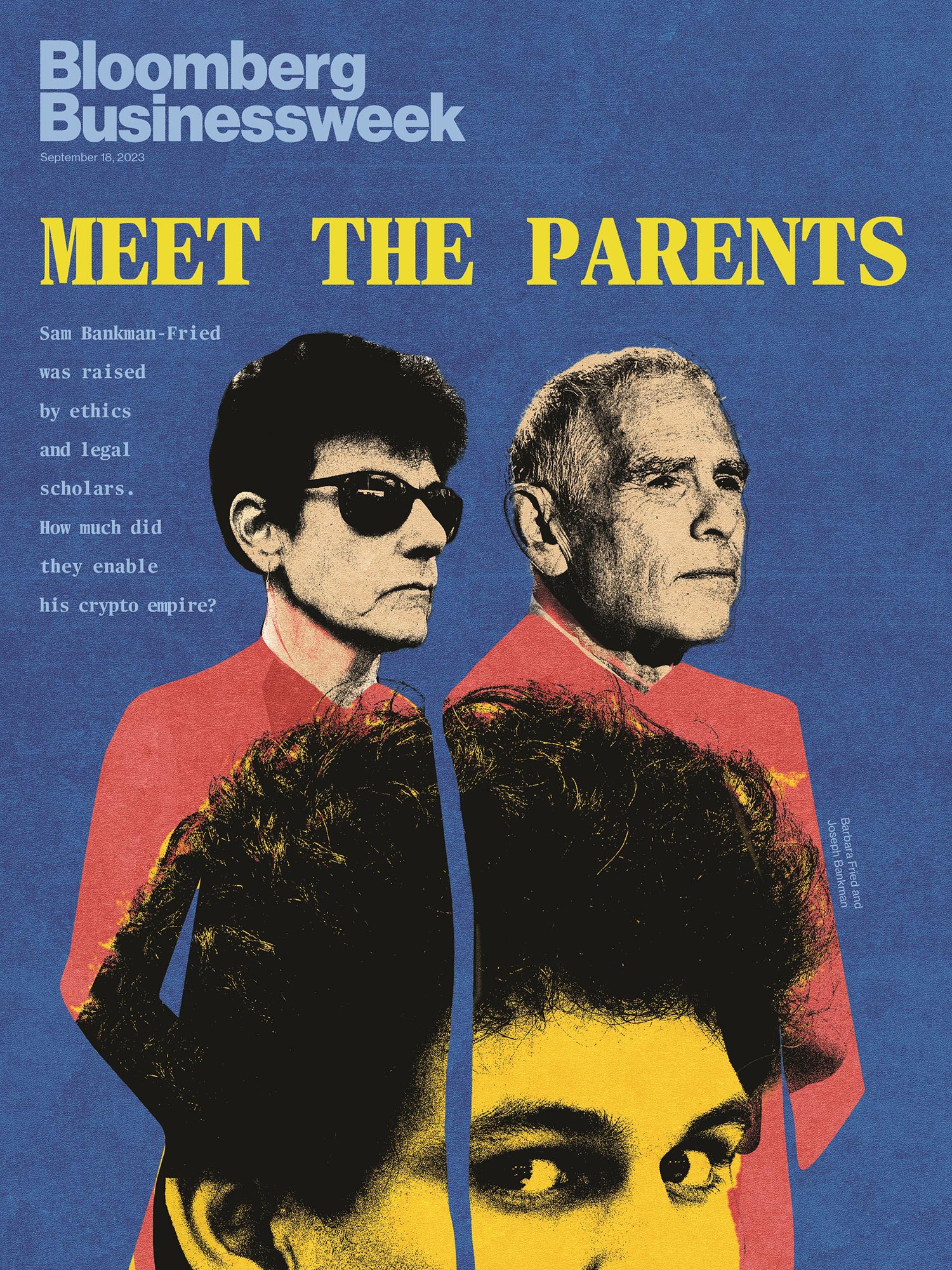

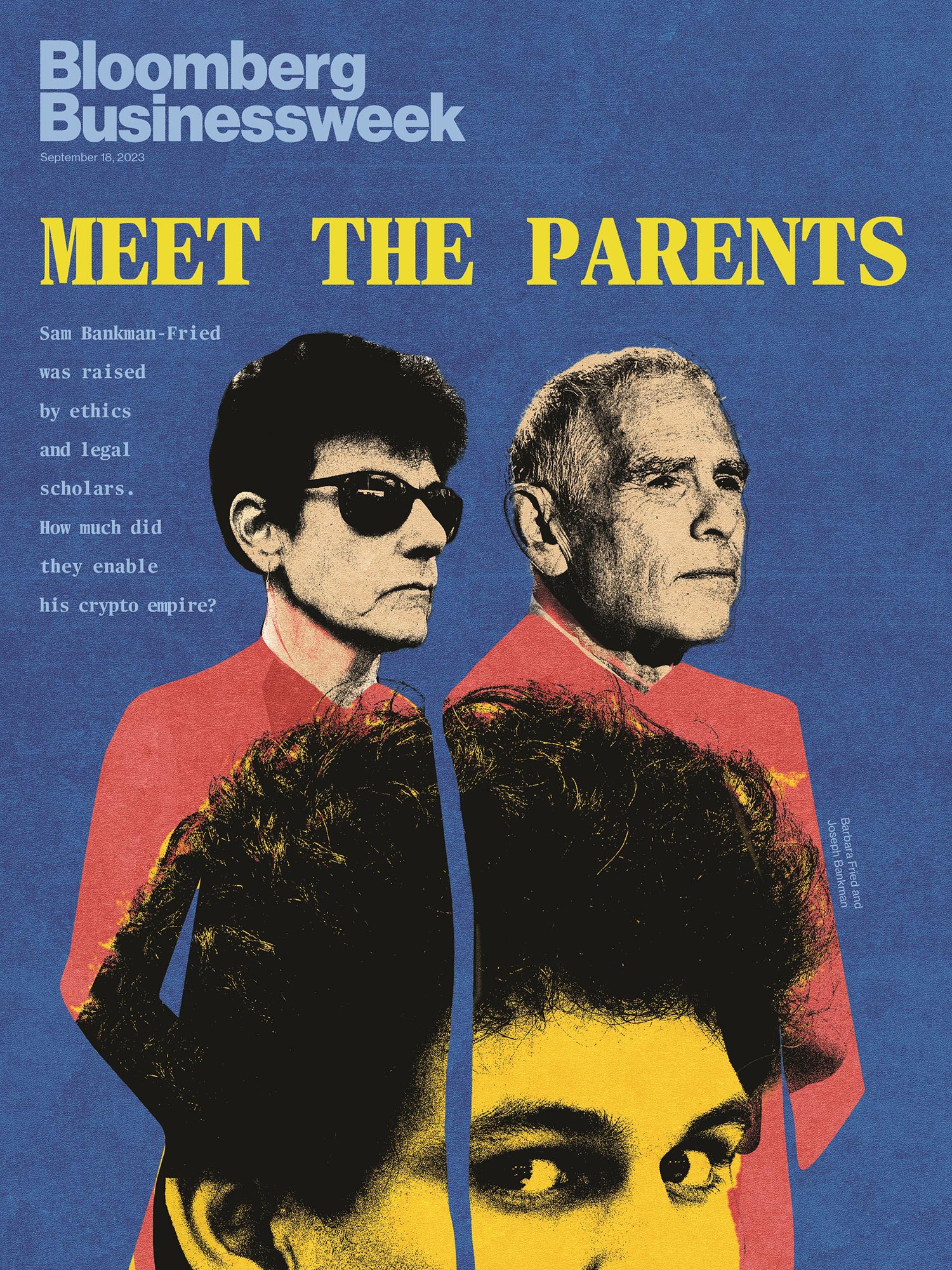

How Sam Bankman-Fried’s Elite Parents Enabled His Crypto Empire

Joseph Bankman and Barbara Fried, both renowned Stanford scholars, opened doors for their son and provided a halo effect for his company.

Photo illustration: Arsh Raziuddin; Photos: Getty Images; Josh Edelson

LONG READ

By Max Chafkin and Hannah Miller

September 13, 2023

Around the Bankman and Fried house, Larry David was a family favorite. So the parents were understandably excited when they got the email from their son Sam. He wrote that his company, FTX, would be airing a commercial during the 2022 Super Bowl and that David was starring in it.

The curmudgeonly comedian would play a series of skeptics throughout history, basically Neolithic and Elizabethan versions of his character from HBO’s Curb Your Enthusiasm. Someone would present an invention—the wheel, the lightbulb, the Walkman and, finally, FTX—and David would dismiss each one in quick succession. The ad would warn viewers that if they didn’t invest in crypto, they were missing out on an historic opportunity to get rich. The tag line: “Don’t be like Larry.”

Sam Bankman-Fried’s parents loved it. “Surreal,” wrote Barbara Fried. His dad, Joseph Bankman, gushed over how happy and proud he was. A few days later, employees received some additional feedback from Sam’s younger brother, Gabe. He asked if his dad could have a role in the commercial, saying he was too humble to make the request himself.

The request was odd in a sense. Bankman had no formal role at FTX at the time. Nor did Gabe, who was running an FTX-backed nonprofit dedicated to preventing pandemics. But executives at FTX understood that corporate roles, especially as they related to the co-founder and chief executive officer, were much blurrier.

Not long afterward, Bankman showed up on set for a scene in which David vehemently opposed the Declaration of Independence. When told “the people shall have the right to vote,” David responded incredulously: “Even the stupid ones?” Bankman, wearing a powdered wig, shouted, “Yes!” FTX paid roughly $20 million to create and air the 60-second spot. Around the same time, Bankman joined the company as an employee.

A screenshot of FTX’s Super Bowl commercial with Larry David.

Source: YouTube

A person familiar with the commercial’s production—who, like most people interviewed for this story, requested anonymity to avoid being associated with a messy bankruptcy, numerous class-action lawsuits and several criminal cases—says the decision to give the boss’s dad a role made a certain sense within the upside-down logic of FTX. In a way, Bankman was the company’s founding father.

QuickTake: The Crypto Fraud Case Against Bankman-Fried and FTX

Both parents have distinguished careers that long precede their son’s alleged fraud. They met in the 1980s at Stanford University, where they taught at the law school for more than three decades, living on campus and raising two sons. Bankman, an expert on taxes, is renowned for his work making the US tax code friendlier to lower-income citizens. Fried, an authority on legal ethics, was prominent in progressive political circles.

At the time the ad aired, critics were warning that FTX was luring naive investors with extremely risky financial instruments that were mostly banned in the US. Those investors would see their money vanish when the funds were diverted, without their knowledge, to a hedge fund that Bankman-Fried also owned. FTX collapsed and filed for bankruptcy in November 2022.

Featured in Bloomberg Businessweek, Sept. 18, 2023.

Photo illustration: Arsh Raziuddin; Photos: Getty Images; Josh Edelson

Leading the bankruptcy process is John Ray III, who did the same for Enron and has described this case as worse. He’s accused Bankman-Fried of using customer funds to enrich himself, as well as his family members and other insiders, and is seeking to reclaim some of that money. More ominous for the Bankman-Frieds is the criminal case, set to begin in New York City on Oct. 2. Prosecutors haven’t accused the parents of wrongdoing, but charges against their son, whose net worth at its height was estimated at $26 billion, include fraud, money laundering and bribery. The case could send Bankman-Fried to prison for the rest of his life. He pleaded not guilty and has characterized the losses as the result of inept, but not criminal, management.

Bankman and Fried have steered clear of much of the scrutiny that’s enveloped FTX. That’s at least in part because they’ve yet to deliver a full accounting of their roles in helping their son build a sprawling business and political-influence operation. Instead, they’ve generally been portrayed as spectators, who, often in tears, offer emotional support to their son at frequent court appearances. But their names will almost certainly come up during the trial. The defense team has signaled its strategy may, in part, rest on advice Bankman-Fried received from lawyers, including his parents.

A spokeswoman for the couple, Risa Heller, declined to make Bankman or Fried available for interviews. She’s said previously that neither one had much to do with FTX beyond being a supportive parent. Fried never worked for the company, and Bankman’s brief tenure mostly focused on philanthropy, according to Heller. Last year, Bankman-Fried told the New York Times that his parents “weren’t involved in any of the relevant parts” of his company.

Former employees and business partners say this wasn’t the impression they had at the time, and legal filings suggest Bankman and Fried were crucial to their son’s transfiguration from schlubby startup nerd to hyperconnected crypto mogul. The couple profited tremendously from FTX, netting $26 million in cash and real estate in 2022 alone. They were regular fixtures at the company’s offices, offered words of encouragement to employees and were included in internal company communications. Their reputations and connections were essential to FTX’s success.

Their kid seemed “bred for the role of crypto exchange founder and CEO,” as a fawning profile published by Sequoia Capital, one of FTX’s biggest investors, put it. The article, which attempted to explain why one of Silicon Valley’s most respected venture capital firms had chosen to give $150 million to a young man who was caught playing video games on his computer in the middle of an investor pitch meeting, offered two pieces of evidence in support of its assertion. The first was that Bankman-Fried worked briefly at a Wall Street trading firm. The second was that his parents were Stanford law professors.

No one in Silicon Valley likes to think of themselves as privileged. Ayn Rand-reading VCs and entrepreneurs tend to bristle at the suggestion that their decisions are anything other than a product of calculated reasoning. Yet the valley’s knee-jerk elitism is so blindingly obvious that it seems almost beside the point to bring up. Investors overwhelmingly favor companies run by White men, often hailing from a tiny group of elite colleges, while shunning anyone who deviates from their superficial sense of what a successful founder should look, talk and act like. Some openly discriminate against founders over the age of 30, against founders with an accent and against anyone who comports themselves as if they’re not already rich. God help you if you show up to a pitch meeting wearing a suit.

The most privileged place within this world of extreme privilege is Stanford—the birthplace of companies such as Hewlett-Packard, Sun Microsystems, Cisco, Yahoo!, Google and PayPal. Fried—a product of Harvard, Harvard Law School, the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit and the law firm Paul, Weiss—arrived in 1987 as a tenure-track professor and rented a house on campus. A year later she met Bankman, a graduate of the University of California at Berkeley and Yale Law School who’d come to Stanford on a trial teaching gig after practicing as a tax lawyer in Los Angeles. Barb and Joe, as they’re known on campus, went public with their relationship after Bankman secured a tenure-track job the following year. They moved in together, and when Fried’s rental came up for sale in 1991, they bought it.

The Bankman and Fried house on Stanford’s campus.

Photographer: David McIntyre/Zuma Press

The home where Sam Bankman-Fried grew up, and where he spent the first half of 2023 under house arrest, sits at the end of Cooksey Lane. It’s valued at $3.6 million, though that’s more the result of Palo Alto’s decades-long real estate boom than a comment on its luxuriousness. The home is a fairly modest gray Craftsman, with four bedrooms, three bathrooms, a generous porch and a swimming pool, sitting on a big lot surrounded by tall trees on all sides. Just behind the property is the Lou Henry Hoover House; the modernist estate, once home to former President Herbert Hoover, is where Stanford’s own president lives.

During his childhood, Bankman-Fried was surrounded by a revolving group of youngish intellectuals—law professors and law students, of course, but also sociologists, engineers, artificial intelligence researchers, classicists and social scientists. On Sunday nights, Bankman would order takeout or cook something simple like pasta, and they’d cram 15 guests into the dining room and sit and talk, often about philosophy and politics. Sam and Gabe, even as teenagers, sometimes joined in the conversation. Bankman and Fried were proud and committed do-gooders. The couple didn’t marry because, as they told friends, it was unfair that same-sex couples couldn’t do the same. “They felt that they should not take advantage of something that wasn’t open to others,” says Paul Brest, a former dean of Stanford Law School and a longtime friend. “They’re deeply ethical people.”

Bankman at Stanford Law School in 2021.

Photographer: Josh Edelson

In his younger days, Bankman had a mop of dark, curly hair, which his son would inherit, along with an ingratiating manner, which his son would not. The couple sent their kids to Crystal Springs Uplands School, a $60,000-a-year prep school packed with Silicon Valley’s nepo babies. By then, Bankman had become one of the foremost experts on American tax policy. He advised California’s government on a pilot program to let the state do people’s taxes for them. The program attracted fierce opposition from tax preparation companies and small-government absolutists and made Bankman something of a hero to reform-minded liberals.

To fellow academics, Bankman was an empathetic and forgiving mentor. Jay Soled, a Rutgers University professor, recalls Bankman comforting him after he fumbled a presentation. “That was the kind of guy Joe was,” he says. “There would be a next time, and you could only improve.” In 2009, while still teaching a full course load, Bankman enrolled in medical school to become a clinical psychologist. After completing his internship, he began moonlighting as a cognitive behavioral therapist while teaching an optional class, developed with Fried, to help law students manage anxiety.

Fried was an even bigger intellectual than her husband and, though well liked on campus, she has a reputation for provoking anxiety among students as much as for helping them manage it. Her academic work centers on a branch of ethics known as consequentialism, or the idea that the results of our actions are more important than abstract notions of right and wrong. These ideas became something of a family religion. The philosophy is about doing good for as many people as possible, but a less charitable way to summarize it is “the ends justify the means.”

FriedPhotographer: Brittainy Newman/The New York Times/Redux

Fried’s most famous paper focuses on the “trolley problem,” the well-known thought experiment involving a train destined for tragedy. It was mostly used by philosophers to debate ethical choices: Should you divert a train and kill someone standing on the next set of tracks or do nothing and let a crowd of people on the main path die? Fried’s paper argued that the problem was bunk and obscured the real-life moral choices policymakers face—for instance, how much aid to give to the poor or how much health care to give to the uninsured. “There are hundreds of thousands of pages written on this,” says Brest. “My sense is that after Barbara finished with the trolley problem, there wasn’t anything left to be said.”

Bankman-Fried put his mother’s self-righteousness at the center of FTX’s marketing. His company might be officially in the business of selling crypto, but that was merely a way to generate revenue for lifesaving causes. An advertising campaign that ran in major fashion magazines and featured Bankman-Fried and the Brazilian supermodel Gisele Bündchen included a quote from the FTX founder: “I’m in on crypto because I want to make the biggest global impact for good.” Fried’s work would be a recurring trope in profiles of her son and was often used to suggest Bankman-Fried was a less cynical breed of billionaire.

Fried’s second-most-famous article is more relevant to her son’s current situation. Published in 2013 as a cover story in the Boston Review, a highbrow quarterly magazine, the essay argued for a more lenient approach to dealing with lawbreakers. “The philosophy of personal responsibility has ruined criminal justice,” Fried wrote. Her article’s title: “Beyond Blame.”

Bankman-FriedPhotographer: Stephanie Keith/Bloomberg

Promises of do-goodery aside, running a crypto business was always legally complicated. Bankman-Fried started a hedge fund called Alameda Research in 2017 to exploit price differences between cryptocurrencies traded in Asia and those in the US. Soon the fund was moving huge sums of money between continents in ways that looked—as he boasted on a podcast—exactly like money laundering. Alameda struggled to open bank accounts.

Bankman-Fried needed lawyers. Fortunately, a very, very good one was available. His dad wasn’t an expert in crypto, but at the time Alameda started, no one was. “From the start, whenever I was useful, I’d lend a hand,” Bankman said on an FTX podcast in August 2022. Noting the company didn’t have lawyers at the time, he added, “I think my utility there was pretty obvious.”

Former Alameda staffers say Bankman helped draft early legal documents. Invoices from Fenwick & West, Alameda’s law firm, list him as an attendee in meetings, showing he was involved not only on tax issues but also in the development of marketing materials for FTX and FTT, the made-up currency Bankman-Fried issued when he launched his crypto exchange and the flimsy asset on which a Jenga tower of imagined wealth would sit.

FTX was based in Hong Kong, until the government there began cracking down on crypto in 2021. A person familiar with FTX’s operations says Bankman played a key role in the decision to relocate to the Bahamas, where there were few restrictions on digital currencies. The specifics were arranged by someone Bankman personally recruited—Daniel Friedberg, a former Fenwick & West lawyer who became FTX’s general counsel.

To his employees, Bankman-Fried gave the impression he consulted his dad constantly. When someone would offer a legal suggestion, he’d often say it sounded good but he wanted to “call Joe” first, according to a former staffer, who added that almost all the lawyers who worked for Alameda seemed to be friendly with Bankman.

Other ex-employees say that, especially compared with Bankman-Fried—who sometimes struggled to make eye contact and could be blunt, bordering on cruel, when dealing with employees—the father had a way with people. Training as a psychotherapist had made him an excellent listener, and he was an energetic conversationalist. He asked employees about their personal lives, joined in for games of padel (a pickleball-like sport that employees were crazy about) and showed up at company dinners. Fried also attended FTX dinners but appeared less frequently in the office. They both served as mediators between staff and their child. If Bankman-Fried said something mean or indecipherable, his dad would try to translate or simply say he understood his son could be difficult. He was seen, another employee recalls, as a “cute old man,” a capable but nonthreatening figure who was there to keep his son from losing control.

But the most important role Bankman and Fried played was to give their son credibility with people who might not otherwise be inclined to do business with a sketchy upstart. In 2021, when Bankman-Fried approached Sequoia Capital about making a big investment, the firm was interested in backing a global crypto exchange but had concerns about potential legal and regulatory risks, according to two people familiar with the deal.

“I think Joe wanted to help his son, and he got caught in the quandary of what was happening. You want to think the absolute best of your kids”

FTX was based offshore and operating on the edges of the law. The founders of many competing firms seemed, to put it mildly, ethically flexible. Binance’s Changpeng Zhao was under investigation by authorities in the US and elsewhere. He denied wrongdoing but refused to say where, exactly, his company’s headquarters was. The co-founder and then-CEO of BitMEX, Arthur Hayes, had been indicted for failing to try to stop money laundering on the platform. According to a federal criminal complaint, he’d bragged that he’d based BitMEX in the Seychelles, a tiny East African archipelago, because it cost “just a coconut” to bribe regulators there. He resigned and ultimately surrendered to authorities before pleading guilty.

FTX was in the same basic business as Binance and BitMEX, but Bankman-Fried was adamant that his long-term goal was to secure the approval of US regulators. Plus, he had something those companies didn’t: an endorsement from a former commissioner of the US Securities and Exchange Commission. Sequoia was convinced to invest, say people close to the deal, after a phone call from a prominent ex-SEC official who’d consulted with the firm informally on previous deals and now teaches at Stanford. This former official spoke in support of FTX’s legal strategy—which involved operating overseas while it worked to win approval from US regulators—and said Bankman-Fried also happened to be the son of his friends.

The endorsement was part of a pattern. “Both parents really opened doors for Sam,” says a person who was involved in Bankman-Fried’s effort to get American politicians to embrace his firm.

By that time, Fried had started a left-wing super PAC, Mind the Gap, which styled itself as the Silicon Valley wing of the #resistance movement. The group advised high-profile tech donors, including former Google CEO Eric Schmidt and LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman, on where to direct campaign contributions. The circle of elite donors got a new member in 2020: Fried’s son, who gave more than $5.5 million to Democrats and Democratic Party-aligned groups that year, instantly making him a DC player. In 2022, he gave about $40 million.

Bankman-Fried gave directly to candidates recommended by Mind the Gap. Nishad Singh, a former FTX executive who pled guilty to funneling funds from FTX customers to political causes supported by Bankman-Fried, donated $1 million to Mind the Gap in 2021, making him the PAC’s largest donor for the most recent election cycle. Mind the Gap hasn’t been accused of wrongdoing.

BankmanPhotographer: Eduardo Munoz/Reuters/Redux

Bankman, meanwhile, often accompanied his son to meetings with regulators and elected officials. Bankman also appeared at FTX events as a spokesman for the company’s charitable ambitions. He still advocated on behalf of tax reform, but now he’d sometimes toss in a new interest: crypto.

During his appearance on the FTX podcast, Bankman touted a pilot program he was running in South Florida that would give poor people digital currency wallets in lieu of bank accounts. “If you’re not part of the financial system, everything is harder,” he said. “It’s expensive to cash checks. It’s expensive to move money around. So that’s kind of a national disgrace.” FTX, Bankman promised, was going to fix that.

In magazine profiles and TV interviews, Bankman-Fried professed austerity. He wore beat-up sneakers, lived with roommates and drove a Toyota Corolla—with all of the savings going to charitable causes, he said. “You pretty quickly run out of really effective ways to make yourself happier by spending money,” he told a Bloomberg reporter in early 2022. “I don’t want a yacht.”

In reality, Bankman-Fried and his inner circle spent with such abandon that the office could feel, as the person who worked on the Super Bowl ad describes it, like the Emerald City in The Wizard of Oz. The company bought hundreds of millions of dollars of luxury real estate, including a $30 million penthouse apartment in the fanciest resort in the Bahamas, where Bankman-Fried and his cohorts lived. They chartered private jets for themselves and, because Amazon.com doesn’t consistently service the island, for their online packages. And—as bankruptcy filings would make clear—they even bought a 52-foot yacht. It was purchased by Alameda for Sam Trabucco, the company’s co-CEO at the time, who named it Soak My Deck.

Bankman-Fried’s parents seemed to share in the spoils. They flew first class, sometimes private. After landing in the Bahamas, they regularly stayed in a $16 million beachside apartment. FTX bought that dwelling, along with three dozen others on the island, at a cost of roughly $250 million. Through their spokeswoman, Bankman and Fried have said they saw the home as company property, not theirs.

Bankman-Fried expressed a similar sentiment in an interview at a New York Times conference. “I know it was not intended to be their long-term property,” he said. “I don’t know how that was papered in.”

So here’s how it was papered in: A bill of sale, obtained through a public records request in the Bahamas, shows that on April 7, 2022, Bankman and Fried signed as co-owners of the apartment, with a Bahamian notary as witness. The document makes no mention of FTX and refers to the property as a “vacation home.” “The house was used as temporary housing while Joe worked in the Bahamas,” the spokesperson for the couple said in a statement. “Outside counsel confirmed to Joe and Barbara that FTX would have all beneficial ownership of the house and agreed to document that in writing.”

Around the same time, Bankman received a $10 million gift from his son. A lawsuit filed by Ray, the FTX bankruptcy chief, claims Bankman-Fried got the money by borrowing it from an account that contained customer funds. According to the complaint, he did so after consulting the person who by this point had become a top adviser on legal matters personal and professional: his dad. The lawsuit alleges that the loan was never formalized—there’s no loan agreement, promissory note “or other indication that the funds were not simply taken from Alameda by Bankman-Fried to enrich his family.” His father moved almost $7 million to personal bank accounts; the rest he kept in crypto on FTX.

“It’s hard to wrap one’s head around ‘how could they not know?’ The most sense I can make of it is that it was blind faith. They didn’t have the full picture”

Given the rising prices of digital currencies at the time, keeping some of his nest egg on FTX might’ve seemed like a logical decision for Bankman, not to mention an opportunity to live his newly adopted values, but within months a marketwide selloff caused him to lose $1 million and ultimately endangered FTX itself. As the company lurched toward insolvency, Bankman-Fried publicly claimed all was well while turning to his father to help minimize the damage. “FTX has enough to cover all client holdings,” he wrote (and later deleted) on Twitter, the social media platform now known as X. “We don’t invest client assets.”

Behind the scenes, his father was offering a very different, and ultimately more honest, message: FTX was in trouble and needed cash. On Nov. 7, when Bankman-Fried was posting falsehoods, and the next day, he and his dad were holed up with other executives, trying to deal with what they characterized as a bank run, says a person with knowledge of the operation. Bankman communicated the same to investors, including the short-lived Trump White House press secretary and financier Anthony Scaramucci, who says he first heard about FTX’s troubles on Nov. 7.

Scaramucci says Bankman, in a phone call that morning, described a “liquidity mismatch” of roughly $1 billion. But in a second call later that day, Bankman said the figure was actually $4.5 billion. Finally, Scaramucci heard from another FTX employee who said the real amount was $7 billion. “I think Joe wanted to help his son, and he got caught in the quandary of what was happening,” Scaramucci says. “You want to think the absolute best of your kids.”

Bankman-Fried with his mother in a Nassau courtroom.

Photographer: Katanga Johnson/Bloomberg

In the days that followed, Bankman was included on emails to the Bahamian attorney general and the country’s top securities regulator, who’d been tipped off about the possible misappropriation of funds and were sending increasingly frenzied messages asking, in short, what the hell was going on. Bankman-Fried, cc’ing his dad, attempted to put them off. He mentioned a “liquidity gap” and promised the company was doing its best to find investors. In a subsequent email, which his father was also copied on, he offered to pay back Bahamian investors before anyone else—an offer that federal prosecutors have suggested was an attempt to, essentially, buy influence in the country.

Just before the bankruptcy filing, Bankman urged regulators and creditors to avoid rushing to judgment. His initial position, says the person familiar with the discussions, was that FTX’s managers were just kids who’d made a mistake. They’d give the money back, he explained, and then everyone would be able to move on with their lives.

Bankman and Fried didn’t, however, try to return the cash gift. They haven’t explained why, but Ray’s lawsuit, filed on behalf of FTX’s creditors, suggests a reason: They need the money to fund their son’s criminal defense.

Members of the media await Bankman-Fried’s arrival at a Bahamas airport for extradition to the US on Dec. 21, 2022.

Photographer: Tristan Wheelock/Bloomberg

Bankman-Fried was arrested in mid-December, extradited to the US and released on bail. The bail package, $250 million, was secured by bonds from two of his parents’ colleagues at Stanford, as well as the deed to the family home, where Bankman-Fried was ordered to live while he awaited trial. The sudden turnabout was jarring to friends and Stanford faculty members, who’d only just gotten used to the idea that the kid they’d seen at Joe and Barb’s was a crypto billionaire. Now they were attempting to wrap their heads around the accusation from prosecutors that he’d actually been the mastermind of one of the largest frauds in US history. Security barriers went up, blocking the road leading to the house. Students and members of the media stopped by to gawk; the Bankman-Frieds bought a German shepherd, they told friends, because they were worried about their safety.

“There was all this morbid intrigue,” says Tim Rosenberger, who graduated from the law school earlier this year. “Were they going to hire a new professor? Who was going to teach tax law?”

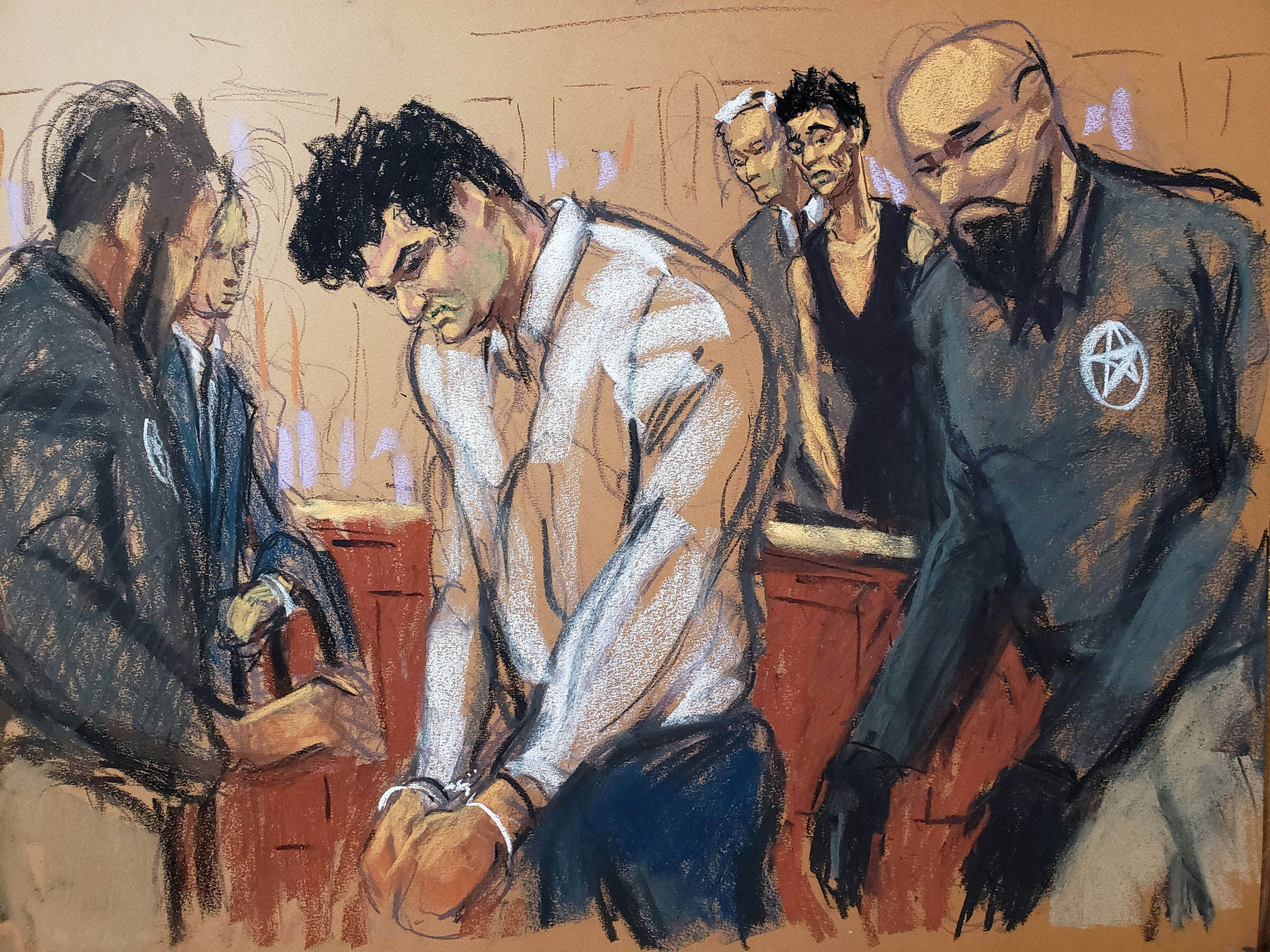

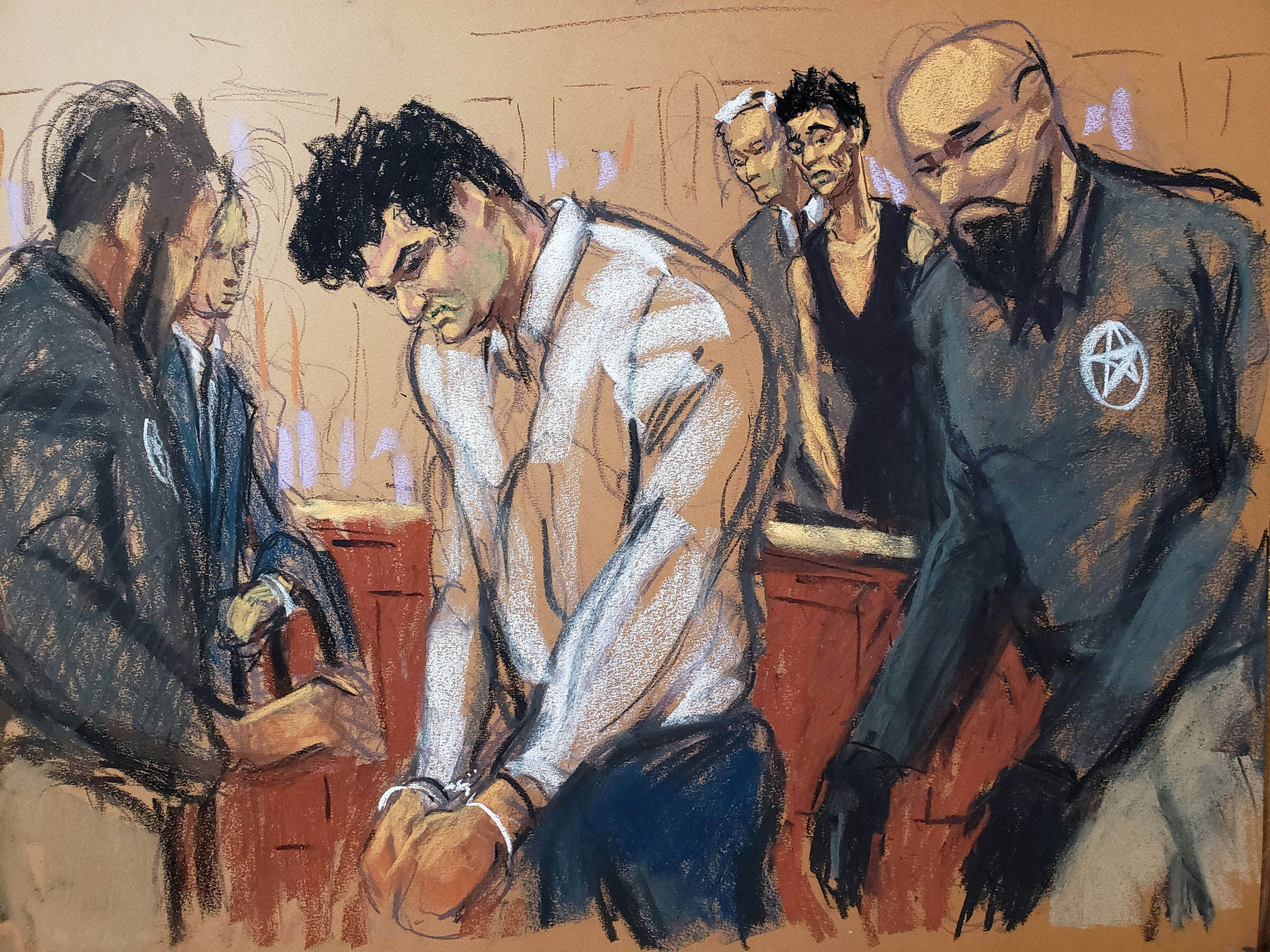

In group chats populated by former FTX employees, a debate has raged over whether Bankman and Fried knew about the alleged crimes. Friends of the couple, meanwhile, have struggled to fathom how two people who were famous for being ethical could have been so close to such a massive ethical lapse. In August prosecutors accused Bankman-Fried of leaking damaging information about a former employee as part of an attempt to intimidate witnesses. His lawyers denied the charge, but he was sent to Brooklyn’s Metropolitan Detention Center.

As her son was taken into custody, Fried, who’d been watching tearfully from the spectators’ gallery, tried to approach him. “That’s my son!” she said when a US marshal stopped her. She watched as Bankman-Fried, following standard protocol, removed his jacket, took off his tie and bent over to remove the laces from his dress shoes. Bankman held his arm around Fried’s shoulders while she sobbed.

A courtroom sketch of Bankman-Fried’s arrest after a US federal judge revoked his bail.

Source: Jane Rosenberg/Reuters/Redux

Friends say they’re worried about the couple. Since Bankman-Fried’s arrest, neither parent has taught a class. Bankman canceled his courses, and Fried, who retired from the school two months before FTX’s collapse, resigned from her political nonprofit. “To have something like this happen to a family of intelligence and public spiritedness,” says John Donohue III, a fellow Stanford professor and longtime family friend, “that’s devastating.”

“It’s hard to wrap one’s head around ‘how could they not know?’ ” says another friend, who requested anonymity. “The most sense I can make of it is that it was blind faith. They didn’t have the full picture.”

That’s certainly plausible. If the narrative laid out by prosecutors is accurate, Bankman-Fried was sociopathic in his deception—conning not just investors but also business partners and even his own employees. It’s not a stretch to think he might have used his own parents—along with their towering academic careers—to pump an exploitative enterprise. Bankman-Fried claimed to be a billionaire many times over. Why shouldn’t he buy his mom and dad a nice home? And why shouldn’t his dad get to hang out with Larry David on a Super Bowl shoot?

But even if they didn’t know about the alleged misappropriation of funds, critics say, the parents deserve part of the blame. Fried’s ethical compass could explain how her son might have been able to overlook obvious moral failings in service of what he perceived as the greater good. To follow this train of thinking: What’s a little misappropriation of funds if the end result is billions of dollars for world-saving charities?

Meanwhile, Bankman was involved in providing legal advice that now looks, at the very least, less than sound. He participated in a number of decisions—including the launch of FTX, the creation of FTT, the company’s courtship of politicians and the dealings with regulators in the Bahamas—that have been criticized by regulators and prosecutors as potentially illegal. Bankman also was involved in the hiring of Friedberg, FTX’s general counsel, who’s been accused of enabling the fraud and working to cover up efforts to expose it, including by paying off potential whistleblowers. The allegations, made in a lawsuit on behalf of FTX creditors, included a quote from Bankman to his son, urging him to rely on Friedberg “so we have one person on top of everything.” Friedberg has denied wrongdoing and hasn’t been charged with a crime, but critics say there was enough in his background—including a stint at a Canadian online poker website that was accused of cheating players while he was there—to give pause to someone with a clearer set of eyes.

And then there’s Stanford itself. Bankman-Fried’s arrest came just a month after Elizabeth Holmes was sentenced to 11 years in prison in connection with fraud at her medical device company, Theranos Inc. She’d founded the company on campus as a student and had recruited well-known faculty members to serve as employees and directors. The Holmes case—coupled with the resignation of Stanford President Marc Tessier-Lavigne over allegations of manipulated data in several academic papers—has caused some professors and students to ask why the university hasn’t been quicker to identify cases of misbehavior.

Defenders of the university, including Donohue, point out that Stanford wasn’t the cause of Bankman-Fried’s alleged crimes; it was, at most, a backdrop for them. But backdrops matter. Coming from a place such as Stanford and having parents of high achievement changes how the world sees your shortcomings. What might be perceived as a sign of unseriousness—playing video games during a meeting, say—becomes unmistakable evidence of brilliance.

Over the past 10 months, Bankman-Fried has tried to shift the blame to former employees, lawyers and corporate rivals and insisted his mistakes were ones of sloppiness rather than malevolence. “I f---ed up” was how he put it in a planned congressional testimony written before his arrest. He was, he seemed to be saying, just a kid in way over his head.

—With Benjamin Bain, Ava Benny-Morrison, Annie Massa and Katanga Johnson

.jpg)