by B.J. Sabri / January 10th, 2024

Yeah, because investing in the destruction of our adversary’s military, without losing a single American troop, strikes me as a good idea. You should feel the same.

— Congressman Dan Crenshaw

Premise

Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell introduce their book, Hiroshima in America, with this imposing statement, “You cannot understand the twentieth century without Hiroshima.” Equally, we cannot understand the twenty-first century without knowing why Russia intervened in Ukraine.

Introduction

U.S. proxy war with Russia by way of Ukraine is intensifying and maybe reaching a critical mass for direct war. Despite its military intervention, Russia was not seeking confrontation with the United States—no casus belli. Nor was Russia the one who started the slide towards near-direct hostilities—the United States did. To stress a cardinal point from the onset, the conflict in Ukraine cannot be discussed cogently without addressing the two factors that propelled it: U.S. imperialist and hegemonic agendas.

Prime Minister Victor Orban of Hungary, a NATO country, clearly understood the situation. He explicitly pinpointed to the U.S. feverish drive for a military faceoff with Russia. He said, “The United States has not given up its plan to squeeze everyone, including Hungary, into a war alliance, to go with the crowd”. Orban’s “war alliance” remark is the key to decode U.S. intentions.

While engaging in extremist anti-Russian policies and despite all fanfare, the United States is surely worried to engage Russia in a direct war. Inducing others to sanction, isolate, or fight a proxy war before moving to the next phase is a convenient U.S. strategy to intensify anti‑Russian punitive measures. Depleting Russia’s conventional military resources, test its weapon systems, and uncover its strategic assets are just a few examples of such measures.

So far, the United States, Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and other Western vassals, have been pouring billions of dollars and advanced weapons in support of the fascist Ukrainian regime. What the United States appears to be hoping for is a direct WWII-style war pitting various European national armies against Russia. In such scenario, the United States would be the overseeing godfather of war but without directly involving its own military.

Even so, with stakes so high and dangers so explosive, an expanded U.S. war against Russia via some European states does not come without potential perils to the hyperpower. Now, by taking into account the steady flow of weapons to Ukraine, never-ending sanctions on Russia, and the decision to avoid nuclear confrontation, the United States seems betting on long ball tactics to weaken Russia through protracted pan-European war of attrition.

On the subject of U.S. role in Ukraine, Donald Trump externalized the inner thinking of the ruling establishment when he stated that Ukraine is “A European problem”. Trump’s assessment is not as simple as it sounds. Was he proposing that the United States should stay away from what he called European problems because Ukraine is geographically European and, therefore, Europe should be in charge of resolving the conflict? How does Russia fit in this scheme anyway since it is partially located in Europe?

If this is a “Trumpian continental doctrine”, then one may ask, why is the United States not leaving the Taiwan issue, for example, to be resolved by Asia— or, congruently, by China and Taiwan without interference by outsiders? Because the issue that Trump raised is not about “continental responsibility”, then what hides behind his remark—especially knowing that with its 750 military bases in at least 80 countries, geography was never a barrier to its interventionist actions anywhere in the world?

Trump is an open book. He obliquely put forward the insidious idea that NATO governments should be the ones fighting Russia on behalf of the United States. Trump, a hyper-supremacist demagogue, and a know-it-all charlatan glossed over a fundamental fact of modern wars: geographic location of an armed conflict is utterly unimportant. Proving this point, U.S. imperialist wars against Korea, Viet Nam, Iraq, Serbia, Afghanistan, Syria, Yemen, and Libya are just a few known examples whereby geography posed no appreciable logistical hindrance.

Contrary to U.S. and European propaganda, the ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine is neither a European nor an American problem. By strict logic and on technical ground, it cannot be but a bidirectional affair tying two adversaries (Russia and Ukraine) in a violent struggle to untie tangled geodemographic and territorial issues, as well as legitimate Russian security concerns relating to NATO’s planned expansion to Russia’s borders.

Logic and technicalities could surely elucidate many things. But they cannot dialectically explain why Russia moved into Ukraine in that particular point in history. Regardless of timing, Russia’s intervention was not sudden, was not an invasion, and was not aggression. Rational thinking and pertinent analysis of the events leading to the conflict cannot support counter-arguments to the opposite. As such, the conflict cannot be reduced artificially to geodemography and inter-state contentions. Something else exceedingly larger than Donbass and Ukraine must have been smoldering under the ashes—what is it?

The day after Russia crossed into Ukraine was a scene without equal. The United States, or by antonomasia, the top aggressor, warmongering, and interventionist power in history, mobilized its massive propaganda outlets to inveigh against Russia—dubbed as invader, criminal, and aggressor. Within just a few hours, manufactured pandemonium followed. Russia was put inside the bull’s-eye and targeted for cancellation.

American planners took two bellicose steps to antagonize Russia and worsen confrontation. First: they embraced the Zelensky’s regime (successor to the stridently anti-Russian regime of Petro Poroshenko) in spite of its fascist stance toward Russians and Russia. U.S. propagandists called that embracement “solidarity” with Ukraine and love for its “democracy”. Second: they circulated the illusion that Ukraine, with the U.S. and NATO’s help, could defeat Russia.

I discussed the first step below. As for the second step, because the United States well knew that Ukraine is incapable of defeating Russia, why keep selling the illusion that it could? The grandstanding plan behind the U.S. ruse is perceptible: to keep the war going by putting U.S. and NATO’s military resources at the side of Ukraine, not much as a fighting force, but as a supplier of money, weapons, and training. Considering Russia’s formidable military history, it is unlikely that heavy Western involvement has any chance of turning the tables on the predictable outcome of war.

That did not stop U.S. war planners from adjusting aims and tactics. In no time, the Afghan model was ready for re-use: a proxy war while inundating Ukraine with empty slogans of pending victory. But that model has no chance of succeeding in Ukraine. There is a fundamental difference between the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan and that of Russia in Ukraine. Leonid Brezhnev intervened in Afghanistan to support its communist government, not to alter its borders or resolve ethnical and territorial disputes. The distinction is important. It meant that Russia could have left Afghanistan at will if circumstances were to change—this is what Gorbachev did in 1989. He withdrew all Soviet forces. Conversely, Vladimir Putin intervened in Ukraine for reasons that go way beyond Donbass or the future of ethnic Russians living in Ukraine.

As for the first step; i.e., the American embracement of the Ukrainian regime, by history and by imperialistic tradition, the United States has never been in the business of solidarity. Solidarity in the American lexicon of imperialism is a meaningless term—except when the U.S. is executing a plan but is pretending otherwise. What matters to the U.S. is the consolidation of geopolitical and strategic gains—even if their action could result in the destruction of the country they purport to help. Observation: U.S. interventions in WWI and WWII do not fit the solidarity model. They were no more than an opportunity to implement hegemonic agendas in Europe and the world. Confirming this is the fact that in both wars, the United States had joined just toward the end of hostilities.

Are U.S. aggressive actions against Russia due to concerns for Ukraine’s territorial integrity or love for Ukrainians? Knowing the voluminous record of U.S. military interventions and rationalizations thereof, the answer is no. As it stands, Russia’s intervention offered the United States the opportunity to confront it for purposes unrelated to the Ukrainian events.

Further, the U.S. claim of solidarity with Ukraine because of Russian “aggression” is dishonest at best. Solidarity cannot be selective. For a claim to be valid, the claimant [United States] must prove that its opposition to aggressions is: (a) rooted in its history, conduct, and ethics; and (b) based on principles thus applied universally. With regard to those elementary requirements, the United States would not only be unable to satisfy but also would fail to prove the contrary.

U.S. propaganda is a gargantuan super-machine that U.S. doctrinaires of empire shape it according to needs. It does not matter if one points to its duplicity, multiple standards, false claims, misinformation, accusations, mirror politics, hypocrisy, projection, and so on. Take. for example, the U.S. propagandistic usage of the aggression concept. The ideologues of U.S. hegemony routinely dub their interventions as “legitimate”, in defense of things such as “values”, “freedom”, “human rights”, fend off “dangers to the security of the hyper-imperialist state”, and all similar memorized recitations. The flip of the coin is predicable: they call interventions by others “aggressions”, “breach of international law”, and so on. All such fancy rigmaroles are manipulative tactics to subvert facts thus creating favorable conditions for intervention.

To refute U.S. claims that it is helping Ukraine resisting “aggression”, consider the example of Palestine. Briefly, no example could ever top how the United States is treating Israeli aggressions against all Arab states—the latest of which is the genocidal assault on Gaza. Known Facts: Israel, an illegal settler state created by Britain and United States on Palestinian lands, has been attacking—with impunity—many Arab countries for decades. Yet, the “virtuous and peace-loving” Zionist-controlled United States and the hypocrite West always reacted with criminal indifference.

It is public knowledge that U.S. imperialists not only condone Israel’s aggressions under the rubric that Israel has “the right to defend itself”, but also brag about their infatuation with the Nazi “Zionist miracle”. (The ongoing Palestinian genocide at the hands of Israel and the United States consequent to the Palestinian resistance movement of Hamas attacking Israel on October 7, 2023 goes beyond the scope of this work.).

Other examples are significant. India and Pakistan have been having countless skirmishes and wars since 1947. One such war was India’s campaign to partition Pakistan. In 1971, India severed East Pakistan from West Pakistan to create Bangladesh. The “virtuous and peace-loving” U.S. and the West reacted by siding with India. In 1982, Margaret Thatcher sent her navy 8000 miles across the Atlantic Ocean to attack Argentina after this country tried to recover its Malvinas Islands (occupied by colonialist Britain during the 18th c.). The “virtuous and peace-loving” West remained indifferent. In that occasion, and while the United States publicly feigned neutrality, Ronald Reagan said,” Give Maggie enough to carry on…”, and Alexander Haig added, “We are not impartial.”

Is the argument that the United States is determined to confront Russia for purposes unrelated to its intervention in Ukraine sustainable? Considering the antagonistic history of the U.S.-Russian relations, the answer confirms the premise. On the other hand, it is axiomatic that whether Donbass remains in Ukraine or goes to Russia is of no critical value to the physical survival of the United States, France, Britain, Germany, Italy, Poland, etc. Now, suppose that Russia would keep Donbass (historically a Russian territory despite its Ukrainian relative majority).

Would that indicate in any way that Russia is seeking to expand its territory at the expense of other Soviet nations by force? My answer is no. Ponder on the following: before February 24, 2022 (the day Russian forces crossed over Ukraine’s international borders) Russia had never threatened any European country. Preponderant meaning: Russia’s problems are confined to U.S.-controlled Ukraine. The implication is self-explanatory: when the U.S., NATO, Canada, Australia, New Zealand are behaving as if Russia was poised to invade other countries, we inescapably conclude that propaganda is preparing the ground for premeditated goals and mechanisms of execution.

Could anyone tell us why U.S. warmongers are frothing like rabid dogs to fight Russia? Could we explain why Poland and Ukraine’s anti-Russian rhetoric goes beyond toxic hatred and far beyond all definitions given to Nazism? Equally, we want to know why the U.S. is pushing Japan to hone its horns against Russia. We also want to know why Joe Biden, speaking from Hiroshima, is promising to extend U.S. “nuclear umbrella” to Japan as if Russia is about to invade it?

Three observations on Biden in Japan: (1) Biden’s disparagement of Japan was painted all over his face—he delivered his remarks from the same city that the United States had incinerated with a nuclear bomb on August 6, 1945. (2) He reminded Japan that the United States was the one who gutted its military power, but now it wants to be in charge of its “defense”. (3) He used the gimmicks of the nuclear umbrella to call on Japan to re-arm. The last observation can be validated by the fact that numerous American politicians are now calling for Indo-Pacific NATO that includes Japan.

On the funny side of things, it is amusing to hear U.S. ambassador to South Africa, Reuben Brigety, saying, “The arming of Russia by South Africa…is fundamentally unacceptable… [and a] deviation from South Africa’s policy of non-alignment”. [Sic]

Could the ambassador enlighten us as how he reached the “sharp” conclusion that arming Russia is “fundamentally unacceptable”? What is the basis for such fundamentality? Specifically, why is the arming of Ukraine acceptable but not the arming of Russia? Also, what is the story with the phrase “deviation from . . .” Are U.S. imperialists keeping logs on “deviations” by foreign governments and ways to correct them?

Further, Brigety seems implying that Russia is a weak country that needs to be armed by others in order to fight. This is disinformation. Despite the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russia is still a military superpower and a top maker and exporter of sophisticated defense systems and offensive hardware at par with that of the United States—if not more.

Understanding U.S. praxis for imperialist control

U.S. strategy for world domination is based on variable expediencies that change according to circumstances. Knowing all that, what is the U.S. expediency to confront Russia in Ukraine? Answer: coerce all potentially coercible countries to punish Russia—even if that could damage their national interests. But coercion thusly applied raises a question. What is the reason behind the United States pushing some countries to maintain neutrality while urging others to align with its anti-Russian campaign? Assumption: the U.S. has run out of options—its blackmail of other nations no longer works.

For example, talking about the U.S. wanting Serbia to impose sanctions on Russia, Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic complained, “Whoever comes [to Belgrade feels their] first obligation is to explain to me that I am a jerk who did not introduce sanctions”. In a similar vein, Foreign Policy Magazine, one among many ubiquitous voices of U.S. imperialism, wonders whether “Too much pressure on African countries to condemn Russia could backfire”. Implication: the United States and allies are not leaving free breathing space for foreign governments to make up their minds independently.

Down in the article, the writers clownishly ask, “Can the West Rally the Rest against Putin?” The psychological problem that afflicts U.S. imperialists is palpable: they invariably put themselves in a different category as in “West and Rest”. Pay attention: while the word “West” denotes geographical belonging, the word “Rest” is indistinct and can be anywhere. Meaning: the Rest is void of identity thus of value except when is being by the United States. With that, a superiority complex is established.

Then they said, “Rally”. Rally how, one may ask? Is that through sanctions, enticement, or threats? Pay attention again: their question does not name Russia as a target for the rallying cry. Instead, it names Putin. On this subject, the United States repeatedly used this ploy (assigning culpability to specific persons) in Nicaragua, Panama, Libya, Iraq, Iran, Serbia, North Korea, China, and elsewhere. Purpose: demonize the top individuals to justify possible attack on their country.

What does it mean when U.S. pressure on other nations does not yield results? Arguably, it is a sign that structural fatigue is fracturing the system that applies it. So, when the United States catapults all sorts of threats and sanctions against any country that deals with Russia—but no one listens except NATO vassals—, the unassailable inference is transparent: Russia’s campaign in Ukraine is finally producing irreparable fracture lines inside the American architecture for world control.

They say history is a teacher. Among the countless things that history teaches, one is telling. At some point in their existence, marauding empires always die during their panting trek for uncontested domination. This explains why U.S. rulers always rely on lies, bribery, calls for “partnerships”, coercion, and threats as a means for obtaining consent. These contraptions cannot be other than venting mechanisms to help coping with the unstoppable weakening of the structural underpinnings of the imperialist enterprise.

Pressure tactics aimed at forcing countries to take anti-Russian stance are so banal that they are worth mentioning. Janet Yellen, Biden’s secretary of the treasury and a vocal proponent of U.S. economic hyper-imperialism, offered a sample. She sent her Nigerian-born deputy (Wally Adeyemo) to Nigeria with the hope that a Nigerian-American might have a better chance at convincing his compatriots to “Pitch African Countries on pressuring Russia”.

Another example is Josep Borrell, EU’s high representative for foreign affairs and security policy. Borrell, a stiff-like-a-stone warmongering ideologue, is unquestionably confused. He suggests that the “European Union should ban Indian fuel made from Russian oil”. In other words, he is directly threatening India not to buy Russian oil or else.

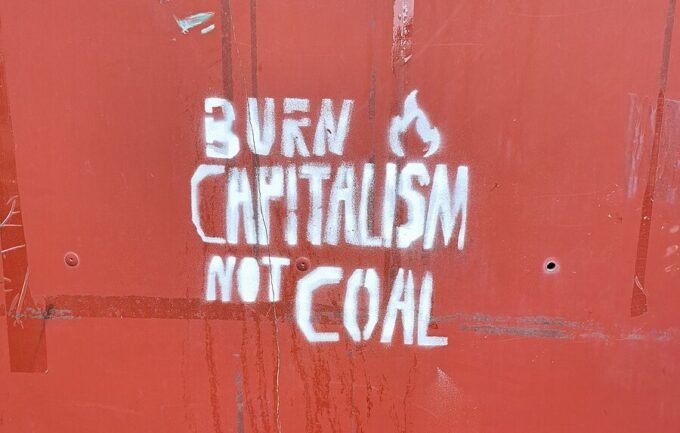

Wait a minute. We were told that in capitalism (romantically dubbed free market economy), when A sells B a commodity, then B becomes its lawful owner. Accordingly, B has every right to resell it. This is how B makes a profit: by buying and re-reselling. In effect, what Borrell wants to do is to stop the sacred totem of capitalism from working when the objective is punishing Russia. Whether capitalism works or not is not the problem. The problem is that Western officials spare no method to destabilize and inflict economic pains on countries that do not share their anti-Russian policies.

A formula-like practice that the United States has been applying and re-applying with tenacity is contradictory dualism. Contradictory dualism, as applied to international relations, goes beyond “what I say is not what I do”, and beyond the outdated formula of “double standard”. Briefly, it is a self-given license to sell a product with counterfeit ingredients. Consider the following limited examples:

- It defends Ukraine’s sovereignty, but it repeatedly violated the sovereignty of countless independent nations;

- It condemns “aggressions” by others, while it is the number one aggressor in the world;

- It prints money on cheap paper but wants the world to accept it as a universal currency;

- It condemns so-called invasions, but it has invaded so many countries with total impunity’

- It makes yearly lists of “state sponsor of terrorism”, while it is the top terrorist state in the history of humanity;

- It claims that it was appalled by crimes of Nazi Germany, but it had committed unspeakable mass murders and genocides that exceeded the motives of Nazism. The near extermination of the Original Peoples, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Eisenhower’s concentration camps for German soldiers, Vietnam, Korea, Iraq, Libya, Serbia, and Afghanistan are indelible examples.

Is contradictory dualism psychological projection? Hardly. Aside from being a tool for making politically motivated decisions, it is a modus operandi powered by interventionist ideology, culture of war, and by a dangerous multi-angled system with its own peculiar legislations and laws. The model has a function. It defines the U.S. in two ways: 1) it confirms the intent to dominate as in the phrase “leader of the free world”, and (2) it presents its own system as epitome of statecraft and unparalleled progress. Is the U.S. a model for an unparalleled progress?

It is a fact that the United States is an advanced country. But U.S. claim of greatness is a matter open for debate. A country with (a) sadistic proclivity for wars and aggressions, (b) structurally flawed financial-capitalistic and political order, (c) gravitational pull toward collapse ($26.3 trillion of foreign debt on October 6, 2023—and still counting), and (d) countless mega social problems, domestic racism, international supremacism, corruption, and degraded civilian infrastructures could never claim entitlement to exceptionalism.

Alternatively, even if the hyper-empire is credited with excellence in every sector, that does not erase the fact that we are dealing with a criminal, lawless, and genocidal entity. Above all, U.S. advancement in medicine, technology, space research, etc., is never an alibi for violent imperialism and wholesale domination, and it is not a license to rule the world. Lastly, a parasitic superpower that exists for the sake of controlling others, to suck up their resources, and to destroy their societies for the benefit of its ruling establishment, its orbiting special interest corporations and their satellite groups cannot possibly possess the accolades it loves to heap upon itself.

In terms of the U.S. ideological doctrines— pivoting around military interventions, coercions, and world domination—a recent statement, again by Janet Yellen, is useful. After minimizing the prospects of war with China, Yellen talked about one such doctrine when she touched on the status of the Chinese economy. Showing off a standard U.S. foreign policy smugness, she said, “China’s economic growth need not be incompatible with U.S. economic leadership”. Translation: you [China] cannot or have no right to grow your economy—if this clashes with our imperialistic economic interests. Yellen’s statement was not casual. She confirmed that in order for the U.S. to consolidate its domination, it must first dominate the modes of production and assets of designated rival states.

To summarize, if we want to evaluate the role being played by the United States in its quasi-direct war with Russia, we need to see all relevant matters in their proper contexts and dimensions. That being said, a protracted war of attrition against Russia would be a U.S. success. It implies that the United States, using others, has managed to force Russia into a corner. It also implies the de facto conversion of U.S. indirect conflict with Russia from war by proxy through Ukraine to war by proxy through most of Europe.

It can be argued that if things go as planned, an indirect U.S. war with Russia through NATO proxies would act as a self-restraining mechanism. Said differently, the United States would protect itself by not engaging Russia face to face. As I stated earlier, a direct conventional American-Russian war could easily turn into nuclear exchange. Again, the logic of such an exchange leaves no space for doubt—destruction for all. Clue: while the United States could care less if Russia is annihilated to the finite particles, it is certainly unwilling to accept its own annihilation.

Related to the preceding, seizing on the opportunity offered by Russia’s military operation in Ukraine, the United States swiftly dusted off decades-old anti-Russian agendas. And, just like that, in the blink of an eye, U.S. rulers turned Ukraine into a daily show and Russia into an existential threat. Seeing the magnitude of the United States involvement in Ukraine, there is no denying that it is looking for any possible way to degrade Russia’s military capabilities by prolonging the war and ruining its economy through sanctions and restrictions on foreign trade. In short, there can be no objective other than weakening Russia to the point of provoking its collapse.

At this time, a dilemma sets in: Russia won’t collapse and the U.S. won’t give up. Is that stalemate before the conflagration? What comes next? In a tweet on X, retired U.S. Army Colonel Douglas Macgregor gives a straightforward answer. He stated, “We have sent almost all of our war stocks, weapons systems and ammunition to Ukraine. We don’t have a great deal left. The war in Ukraine is lost. Make Peace you fools!” Would his exhortation find recipients?

Now, considering the objectives of all forces involved in Ukraine, the first line of enquiry should focus on making questions and trying to come up with some answers. For example,

How Russia’s move into Donbass has changed the rules of engagement with the hyper-imperialist superpower of the United States? Was that move really about Donbass or about the fate of the Russians living in the region—or something else? Is NATO expansion a real problem for Russia? How did it happen that most of NATO countries are aligned behind the United States knowing that post-Soviet Russia never threatened them? Is Ukraine joining NATO a big deal? Why does the U.S. want to preserve NATO as an organization? Why is France (who never won a war as an empire or as a republic) waving its sword at Russia? Why is the United States instigating India against Russia and China? What is the story with Japan’s revanchism and belligerence vs. Russia? Why is the United States pushing for expanding NATO to the East Pacific? Have Russia’s post-Soviet accommodating policies with the U.S. come back to haunt it? Can Russia explain its many foreign policy blunders—especially in taking the side of U.S. imperialism on critical international issues? Are Israel and American Zionists playing any role in the conflict? Does Israel, via the power of the United States, have any specific interest in Ukraine? Where does China stand on this war? Where do the American people stand on the issue of U.S. imperialism and quest to dominate the world? Does that matter anyway? Is the culture of war and violence programmed so deep inside the collective American psyche that it is hard to eradicate? Are fascism, militarism, Zionism, ignorance, and MAGA style political illiteracy driving U.S. hyper-imperialist foreign policy and wars? Is it true that the U.S. wants to dominate the world? Is Russia fighting to end U.S. hegemonic control of the planet, or solely interested in preserving its rights as a sovereign nation? Where do antiwar activists stand on the issue of war in Ukraine? Why is Russia kowtowing to the fascist settler state of Israel, while this effectively is supporting U.S. proxy war in Ukraine? Is the conflict in Ukraine about imperialism vs. anti‑imperialism? Is Russia an anti-imperialist state?

Next: Part 2 of 16

B.J. Sabri is an independent political analyst with focus on the politics, mentalities, ideologies, and praxes of imperialism, neocolonialism, fascism, and Zionism. He can be reached at

b.j.sabri@aol.com Read other articles by B.J..