My trajectory from teenage progressive to democratic socialist.

By Luke Savage

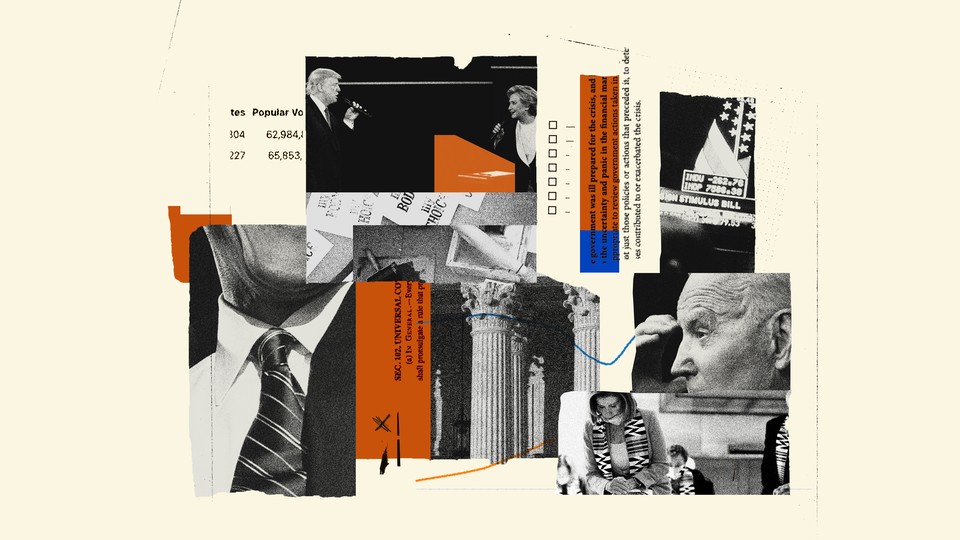

FCIC; Library of Congress; Getty; Joanne Imperio / The Atlantic

OCTOBER 24, 2022

Few people of my generation are ever likely to forget the euphoric evening of November 4, 2008. As networks projected the election of Barack Obama, those around me erupted in a spontaneous outburst of joy and emotion. The setting was the common room at the University of Toronto’s Hutton House, but being outside of America did nothing to dampen the excitement. Borders be damned, the event felt historic in its significance and universal in its implications. To those who assembled for tearful hugs and celebratory drinks in the quad, and to countless others around the world, Obama’s election felt like an epochal affirmation of political possibility—as if some invisible barrier had been shattered or some unconquerable breach in the human experience had finally been traversed.

I will admit to feeling a twinge of embarrassment in describing the innocent and uncomplicated emotions of that night some 14 years later. But I have nonetheless found myself returning to them again and again while reflecting on my own trajectory from teenage progressive to democratic socialist.

The journey to any mature political identity is invariably a complicated one, tracing a winding and sometimes circuitous path with many forks and detours along the way. Which is to say: I did not ultimately turn against the liberal mainstream or become a critic of its most prominent politicians simply because they fell short of my 19-year-old self’s exalted expectations. But watching the liberal political classes of North America and Europe navigate the turbulent events of the early 21st century has been a very real catalyst in pushing me—alongside many others of my generation—to the left.

OCTOBER 24, 2022

Few people of my generation are ever likely to forget the euphoric evening of November 4, 2008. As networks projected the election of Barack Obama, those around me erupted in a spontaneous outburst of joy and emotion. The setting was the common room at the University of Toronto’s Hutton House, but being outside of America did nothing to dampen the excitement. Borders be damned, the event felt historic in its significance and universal in its implications. To those who assembled for tearful hugs and celebratory drinks in the quad, and to countless others around the world, Obama’s election felt like an epochal affirmation of political possibility—as if some invisible barrier had been shattered or some unconquerable breach in the human experience had finally been traversed.

I will admit to feeling a twinge of embarrassment in describing the innocent and uncomplicated emotions of that night some 14 years later. But I have nonetheless found myself returning to them again and again while reflecting on my own trajectory from teenage progressive to democratic socialist.

The journey to any mature political identity is invariably a complicated one, tracing a winding and sometimes circuitous path with many forks and detours along the way. Which is to say: I did not ultimately turn against the liberal mainstream or become a critic of its most prominent politicians simply because they fell short of my 19-year-old self’s exalted expectations. But watching the liberal political classes of North America and Europe navigate the turbulent events of the early 21st century has been a very real catalyst in pushing me—alongside many others of my generation—to the left.

In my early 20s, I tended to view the categories of liberal and conservative as neatly transposable onto a simple left/right binary. Although I never really called myself a liberal, I saw my own commitments as belonging on the same continuum. To be on the left was more or less to be a liberal in a hurry and, insofar as there was any distinction to be made, it was not one of substance but rather of degree.

That view became untenable during Obama’s early years in office. Elected in the throes of the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, the administration rejected any serious overhaul of the financial system, moving instead to keep Wall Street leviathans afloat with injections of federal cash while millions of working- and middle-class people were left to sink. If the president’s 2008 campaign had been a populist cri de coeur for democratic transformation from below, his governing ethos would quickly become technocratic and managerial. No reckoning, it seemed, was to be had with the powerful interests complicit in causing the financial crisis or the many other maladies running through the American body politic. Elite brokerage would take the place of democratic confrontation, and the president would ultimately carry out the rousing slogan “Yes we can” by neutering the very grassroots army that had gotten him elected.

That view became untenable during Obama’s early years in office. Elected in the throes of the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, the administration rejected any serious overhaul of the financial system, moving instead to keep Wall Street leviathans afloat with injections of federal cash while millions of working- and middle-class people were left to sink. If the president’s 2008 campaign had been a populist cri de coeur for democratic transformation from below, his governing ethos would quickly become technocratic and managerial. No reckoning, it seemed, was to be had with the powerful interests complicit in causing the financial crisis or the many other maladies running through the American body politic. Elite brokerage would take the place of democratic confrontation, and the president would ultimately carry out the rousing slogan “Yes we can” by neutering the very grassroots army that had gotten him elected.

The administration would secure its biggest legislative achievement through the Affordable Care Act, which many insisted was an incremental step toward the eventual goal of real universal health care. Only a few years later, as she faced an unexpectedly strong challenge from the Senate’s solitary democratic socialist, Obama’s would-be successor dismissed the idea as a dangerous fantasy that “would never, ever come to pass.” If I had any lingering belief in the reformist impetus of the liberal project, the intransigent centrism of Hillary Clinton’s campaign—and the relentless determination of powerful Democrats to squash and discredit the Sanders movement and its agenda—safely put it to rest.

Years of electoral setbacks and legislative frustrations finally culminated in the defeat of Clintonite triangulation at the hands of Donald Trump. On the night of the 2016 election, an experience as depressing as 2008 was elating, I wondered if the calamity might finally inspire elite liberals to reexamine some of their basic assumptions. For as long as I could remember, the basic contention of liberal leaders had been that, whatever their faults might be, a more moderate approach was the best way of assembling a coalition broad enough to win and keep the right at bay. Faced with the catastrophic rebuttal of that idea, however, they doubled down on old reflexes instead—holding up the idealized image of a pre-Trumpian America in which Democrats and Republicans cooperated, institutions functioned harmoniously, and the long arc of history bent ever so gently toward progress.

Whereas I had once seen the malaise of contemporary liberalism in terms of diffidence and capitulation, these developments (and countless others like them) cast it in a new light. Perhaps the problem was not so much a dearth of courage or a paucity of ambition, but rather a deeper pessimism about the possibility, and desirability, of a politics that looks significantly beyond the horizons of our stagnant present. As the de facto standard-bearers of American progressivism, institutional liberals continue to draw from a lexicon of social justice and moral urgency. Yet even as they adopt the language of exception and crisis, their leaders reject democratic populism and appeal to moderation and consensus instead.

In the Biden era, this contradictory posture has expressed itself through a White House that formally acknowledges existential threats such as right-wing authoritarianism and climate change while maintaining a largely conventional political style concerned with upholding norms. Running for president at the height of a pandemic, Joe Biden could be heard promising to veto universal health care even if a proposal managed to make its way through the House and Senate. Inheriting the most protracted global crisis since the Second World War, his administration has (despite some limited successes) proved unable to implement much of its initially promised agenda of domestic reform. Confronting what they tell us is a new and uniquely malevolent strain of conservatism, liberal operatives spent tens of millions ahead of this year’s midterms to elevate far-right Republican primary candidates who refuse to accept the legitimacy of the 2020 election—part of a questionable strategy to boost the chances of centrist Democrats. Faced with a right-wing Supreme Court’s decision to stampede over abortion rights, the first instinct of many top Democrats was to call for calm, send fundraising emails, and remind people to vote blue in November.

Peter Beinart: Biden stops playing it safe

Though frustration with individual politicians may have been a powerful accelerant, I ultimately ended up on the left because I came to see liberalism’s incessant deference to markets as irreconcilable with its stated commitments to freedom and equality. People are not meaningfully free if they are compelled to spend their waking hours struggling to afford the necessities of life, or if they have to choose between going hungry and seeing a doctor. In a liberal society, the state does protect important political and civil rights. But outside of those things, many must fend for themselves in a chaotic marketplace where they are compelled to compete and trample over others to obtain what’s needed for a dignified life. We therefore need a thicker vision of the common good than liberalism is able, or willing, to offer.

At its best, liberalism represents a rich vein of democratic thought from which conservatives and radically minded reformers alike have long been able to mine. It’s therefore a truism, as the left-wing essayist and literary critic Irving Howe put it nearly 70 years ago, that any genuine “revival of American radicalism will [necessarily] acknowledge not only its break from, but also its roots in the liberal tradition.” At the level of political practice, however, what is generally called “liberalism” today is often small-c conservative in spirit: In language and rhetoric, the soaring cadences of struggle, progress, and reform persist but any profound attachment to them has gradually withered away.

The causes of this development are complex and varied, but the outcome is a form of politics whose managerial impulses have overwhelmed its more progressive ones. Beginning in the 1990s, America’s liberal mainstream conceded many of the core premises of Reaganism and has since largely committed itself to working from within its stifling confines. While some view this turn as a pragmatic one born of political necessity, I have come to think it represents a more lasting ideological conversion. Which is to say: Whatever role bleak memories of George McGovern’s thrashing by Richard Nixon may have had in inspiring electoral caution, I mostly believe liberals of the Clinton era took up the Reaganite religion of unbound markets less because they had to than because they wanted to. Regardless of how we account for this convergence, the upshot has been an ever-narrowing field of political contestation in which fundamental questions are off the table and much of what remains is the orderly management of discontent in an unequal and unstable world.

The obstacles to change and progress today are both daunting and real. But being aware of constraints and limitations in a battle is not the same as refusing to engage in one. When I watched the inauguration of Barack Obama 14 years ago, my younger self could find in his paeans to overcoming political difference and transcending the partisan divide a higher calling to equality, universalism, and cooperation toward the common good. Today, when his successors issue similar refrains, I now hear something else: the exhausted liturgy of a project that reflexively spurns real democratic ambition and prefers to conduct politics as the Tory philosopher Michael Oakeshott once recommended, namely by steadying the ship and refusing to chart a definitive course toward any particular harbor.

The problem is that, while smiling officers cheerfully maintain appearances from the comfort of the upper decks, the ship is sinking, and many of the passengers below have begun to drown.

This essay was adapted from Luke Savage’s book, The Dead Center.

LUKE SAVAGE

Luke Savage is a staff writer at Jacobin magazine and the author The Dead Center: Reflections on Liberalism and Democracy After the End of History.

No comments:

Post a Comment