The two main problems preventing the Ukraine war from ending

Despite some expectations, Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine continues and escalates. Every day, I see horrific images of massive destruction in my hometown of Kyiv, in Kharkiv, and other beautiful cities, which are hard to imagine. Scenes worthy of a disaster movie have become part of our daily lives. Places where we used to walk have been reduced to ashes and ruins. Meanwhile, the Russian invaders are launching new attacks, not only in the east and south, but also in the north, in the Sumy region.

Here in Ukraine, this war truly has the character of a people’s war due to the scale of the population’s participation in the war effort: more than a million people serve in the army, a few more are engaged in critical infrastructure sectors, and many more participate in volunteer activities.

Even my life as a civilian and labor rights activist has changed radically. I receive messages from railway workers who need money to buy drones and other equipment; relatives of workers killed in missile strikes at their workplace inform me of problems with social assistance; nurses near the front lines complain about not receiving the bonuses to which they are entitled. We sometimes manage to overcome these difficulties, but we all want the war to end as quickly as possible.

Of course, the heroic resistance of the Ukrainian defenders and the remarkable special operations carried out on Russian territory have largely contributed to demilitarizing the Kremlin’s war machine. But after losing US military support, Ukraine’s chances of a strategic victory have diminished.

The Istanbul negotiations clearly demonstrated that the Ukrainian position had become much more flexible and aimed for a peaceful solution (a 30-day ceasefire, for example). On the contrary, Russian demands appear even more offensive and aggressive. Thanks to Donald Trump, Russia has seized the initiative on the battlefield, which reflects objective reality. The impossibility of ending the war stems from the weakness of Ukraine’s negotiating position and cannot be overcome by a more drastic mobilization of troops.

So, what are the factors weakening Ukraine?

Problem #1 – The pseudo-pacifism of Western progressive forces

The first problem is particularly painful for me to admit. Many people within the socialist movement traditionally refuse to address issues such as violence, the state, and sovereignty. This leads them to misunderstand the Ukrainian situation. Some of them fail to recognize the decolonial and anti-imperialist nature of the Ukrainian struggle.

This analysis is based on an outdated view of the international system, in which the United States is seen as the sole imperialist and Russia as its victim. Even Donald Trump, who warmly “understands” Putin’s imperialist sentiments, has not changed the conclusions of those who call themselves left-wing intellectuals. The most reactionary regimes in American and Russian history are exerting enormous pressure on Ukraine, while some seek arguments to explain why the attacked nation does not deserve international support. I wonder how the protagonists of the “proxy war” theory cope with the fact that Ukraine continues its fight without direct US assistance and despite its opposition.

Many left-wing activists oppose military support because of their anti-militarist ethos. Providing a sophisticated philosophical motivation for not sending weapons to an invaded country leads to more suffering for innocent people. The contradictory nature of this statement becomes particularly absurd when defended by those who claim to be revolutionaries or radicals... To me, it is clear that these dreamers want to lead a prosperous life within the capitalist system without having any real prospect of overthrowing it. To be against armaments is to reconcile oneself with the evil of slavery.

Living under NATO protection and fearing “excessive militarization” of Ukraine seems hypocritical.

And the opposite: if Ukrainian workers win the war, they will be sufficiently inspired to continue their emancipatory struggle for social justice. Their energy will strengthen the international workers’ movement. The experience of armed resistance and collective action is an essential prerequisite for the emergence of genuine social movements that will challenge the system.

Problem #2: The Ukrainian state’s inability to put the public interest before market interests

Ukraine’s ruling elites promote the free market and the profit-driven system as the only possible way to organize the economy. Any idea of state planning or enterprise nationalization can be dismissed as a Soviet legacy. The problem is that the Ukrainian version of capitalism is completely peripheral and incompatible with mobilizing the resources needed for the war effort.

The prevailing ideological dogmatism places Ukraine in the trap of economic privatization and heavy dependence on foreign aid.

We live in a country where statesmen are rich and the state is poor. The government is trying to reduce its responsibility in managing the economic process and avoid imposing a high progressive tax on the rich and corporations. This leads to a situation where the burden of war is borne by ordinary citizens who pay taxes on their meager wages, serve in the army, lose their homes, and so on.

It is impossible to imagine unemployment during a period of total war. But in Ukraine, there is simultaneously an extremely high level of economic inactivity among the population and an incredible labor shortage. These shortcomings are explained by the state’s reluctance to create jobs and the lack of a strategy to massively involve the population in the economy through employment agencies.

Our politicians believe that the historical imbalances in the labor market can be resolved without active state intervention! Unfortunately, the deregulatory reforms implemented during the war have created numerous disincentives that discourage Ukrainians from finding paid employment. Therefore, the quality of employment must be improved through higher wages, rigorous labor inspections, and ample space for workplace democracy.

Only democratic socialist politics can pave the way for a sustainable future for Ukraine, where all productive forces will work for national defense and socially just protection.

We must now get straight to the point. Without comprehensive military and humanitarian support, Ukraine will be unable to protect its democracy, and its defeat will have repercussions for the level of political freedom worldwide. On the other hand, we must criticize Ukrainian government officials and their inability to end the neoliberal consensus that is undermining the war effort. It would be especially difficult to win a war against a foreign invader when the country faces numerous internal problems related to a dysfunctional capitalist economy.

Life for the empire: Russia’s imperial present in the context of the war against Ukraine

By Adelaide Burgundets

Published 10 June, 2025

First published at Posle.

From its inception, modern Russia’s political system has been shaped by a growing centralization of power. The 1993 Constitution laid the groundwork for what would become a highly presidential system, granting the head of state sweeping powers: the authority to appoint a prime minister without parliamentary approval, to issue decrees with the force of federal law, and to block legislation without jeopardizing his position.

The hyper-presidential system that took shape in the 1990s enabled the federal center to gradually bring the regions under its control. Under Vladimir Putin, this process not only continued but significantly accelerated: regional government authority was systematically curtailed, while financial resources were increasingly centralized. As a result, governors today function more as appointed envoys of the Kremlin than as independent regional leaders, their reliance on federal power effectively eliminating any meaningful autonomy.

Before the adoption of the 1993 Constitution, the Russian Federation operated as an asymmetric state — some regions held greater rights than others. In 1992, for instance, Tatarstan refused to sign the Federal Treaty that outlined Russia’s federal structure. Instead, the republic’s leadership pushed for a separate agreement, arguing that the treaty stripped the region of its sovereignty, previously affirmed by referendum. In 1994, this resulted in the signing of a treaty titled On the Delimitation of Subjects of Authority and Mutual Delegation of Powers, granting Tatarstan the exclusive right to manage its land and resources, draft its own budget, establish regional citizenship, and engage in international relations. Although the Federal Treaty was formally nullified with the new constitution’s adoption, weakening the legal standing of regional powers, in practice the center-region relationship remained largely contractual until the late 1990s.

After Putin came to power, the relationship between the federal center and the regions was fundamentally restructured. Putin urged the constituent entities of the federation to amend their local legislation to comply with the Russian Constitution. As a result, Tatarstan was forced to rewrite much of its own constitution, effectively abandoning its claim to sovereignty. A similar process unfolded in neighboring Bashkortostan, where the regional constitution had also conflicted with the 1993 federal constitution.

Since then, all major decisions affecting the regions have come from Moscow. At the same time, Russia’s formal status as a federation is frequently used to shift responsibility from the center onto regional authorities. In early 2020, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Putin announced a non-working week — a move that placed the financial burden on employers. Just a week later, instead of introducing nationwide measures, he transferred responsibility for handling the crisis to regional governors. As regionalist scholar Natalia Zubarevich put it: “If you’ve handled it well — great. If not, the blame’s on you. It’s a classic system: divide and rule.”

Throughout his rule, Putin has carried out a series of far-reaching changes to Russia’s political system and its mechanisms for controlling public opinion. In 2000, he divided the country into federal districts, each overseen by a presidential envoy tasked with supervising regional governors. Following the Kremlin’s takeover of NTV in 2001, Putin steadily brought all major federal media outlets under state control, silencing independent voices on both national and local matters. In 2004, in the wake of the Beslan school siege, Putin cited security concerns to justify abolishing direct gubernatorial elections. Although Dmitry Medvedev reinstated these elections at the end of his presidential term, this did little to enhance regional autonomy: pro-Kremlin candidates consistently prevailed, aided by administrative leverage and widespread electoral manipulation. These outcomes were made possible by governors’ control over regional resources and their entrenched alliances with local elites.

Financial centralization as a tool of control

The centralization of financial flows has become one of the Kremlin’s key instruments for exerting control over Russia’s regions. The country operates under a three-tiered budget system: federal, regional, and municipal.

The federal budget is funded through the following major sources:Value-added tax (VAT) — 20% of each purchase goes entirely to the federal government. Previously, a share of VAT remained in the regions, but since 2001 it has been fully centralized.

Mineral extraction tax (MET) — all revenues from the extraction of oil, gas, coal, and other resources go directly to the federal treasury.

Tax on additional income from hydrocarbon production.

Corporate income tax — a significant portion (28% out of the 25% total rate, due to overlapping jurisdictions).

Excise duties.

State duties.

Regional budgets receive:85% of personal income tax (PIT);

72% of corporate income tax;

63% of tax on professional income (paid by the self-employed);

Property tax on organizational assets;

Transport tax;

Gambling tax;

Certain state duties.

Municipal budgets are left with just:15% of personal income tax;

Land tax;

Property tax on individuals;

A local trade levy.

This distribution creates a serious fiscal imbalance. In 2024, the federal government collected 35.1 trillion rubles — more than twice the combined revenues of all regional budgets, which totaled 18.2 trillion rubles. The center’s income dwarfs that of the regions. At the same time, nearly a quarter of all regional transfers were allocated to a single recipient: Moscow.

So how is the federal budget spent? Does it return to the regions and municipalities through redistribution? The answer is both yes and no. On one hand, funds are channeled back in the form of grants and subsidies. But more often, these mechanisms serve as tools of political leverage rather than genuine support. Economic dependency reinforces political subordination: the more money a region receives from the center, the less autonomy it enjoys in decision-making.

On the other hand, while the federal budget is designed to redistribute wealth from richer regions to poorer ones, in practice this redistribution is selective and reinforces centralization. A significant portion of federal spending is channeled into the war effort and toward the occupied territories annexed in 2022 — areas that continue to suffer destruction and require constant financial infusion.

Russia’s fiscal system ensures that at the municipal level, not a single locality is capable of balancing its budget through its own revenues. Municipalities are forced to rely on transfers and subsidies from regional authorities, making them politically subordinate to the regional centers. A similar dynamic exists between the regions and the federal government. Most of Russia’s federal subjects are net recipients — they lack sufficient revenues to cover essential expenditures. As a result, nearly every regional governor must routinely appeal to Moscow for financial assistance. For instance, in August 2024, after the Armed Forces of Ukraine entered the Kursk region, the governors of Kursk, Bryansk, and Belgorod requested federal funds to support local territorial defense units — previously financed from regional budgets. In practice, these federal transfers serve to cement regional loyalty to the Kremlin.

As of 2025 only 26 of Russia’s 83 internationally recognized federal subjects qualify as donor regions — regions that contribute more to the federal budget than they receive. This figure excludes the occupied and heavily subsidized territories, including Crimea, Sevastopol, the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk “people’s republics,” and parts of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia. The number of donor regions has grown since the start of the war — not due to improved prosperity, but because the federal government can no longer afford to subsidize an additional nine to ten regions. The consequences of fiscal shortfalls are increasingly visible. Chronic underfunding of housing and public utilities — typically financed at the regional level — has left millions vulnerable. During the winter of 2024–2025, around 1.5 million people were left without heat, including residents of the affluent Moscow region, a long-time donor. One of the largest infrastructure failures occurred there, underscoring the fact that even resource-rich regions struggle to address basic public needs under the current system.

According to 2024 data, eight of Russia’s ten poorest regions are national republics. These regions remain economically marginalized due to a combination of structural disadvantages: traditional economies, geographical isolation, and limited development opportunities. Their economies are largely agrarian, offering low and unstable incomes and exposing residents to seasonal fluctuations. Republics like Tyva and Altai lack natural resources and rely heavily on subsistence agriculture — conditions that make long-term growth unlikely without major investment and structural reforms.

The Federation Council, the upper house of the Russian parliament, was originally designed to represent regional interests. In the 1990s it included governors and heads of regional legislatures, who wielded considerable authority. But since 2000 the body has been transformed: senators are now appointed by governors, most of whom reside permanently in Moscow. The chamber has become largely symbolic — a kind of political retirement home — with little real power.

In 2016 Federation Council Chair Valentina Matviyenko publicly called for a revision of inter-budgetary relations, noting that only 35 percent of tax revenues stayed in the regions, while 65 percent flowed to the federal center. Her remarks hinted at growing internal dissatisfaction, but no structural changes followed. The system remains a mechanism for extracting resources from the periphery to sustain the center — both politically and economically.

Under Putin, this system of hypercentralization has hardened. Legislative reforms, financial controls, and dependency-based redistribution have turned regional governments into administrative appendages of the Kremlin. Their ability to pursue independent policies or address local socioeconomic challenges is severely limited. In this configuration, Moscow emerges as the primary beneficiary, while the rest of the country is left increasingly dependent — and increasingly marginalized. The war in Ukraine, costly and protracted, has only deepened this inequality.

People are the new oil

In 2009, Deputy Prime Minister Sergei Ivanov called people “the second oil.” At the time, the phrase referred to Russia’s human capital. Today, it carries a far more somber meaning.

In wartime, low-income regions have become a major source of military recruitment and mobilization — just as they once supplied cheap labor to major cities. These already-impoverished territories are now being drained of their people for the war effort.

In the fall of 2022, Russia announced a partial mobilization. The manpower shortage quickly became apparent: in just two months, around 300,000 men were drafted. The first casualties among them were reported only weeks after fighting began. Meanwhile, the mobilization decree effectively “trapped” contract soldiers on the front lines, automatically extending their terms of service. Hundreds of thousands of contract servicemen — mostly from poor regions — along with the newly mobilized, are now unable to leave the war by legal means.

In Russia, conscription is often referred to as a “poverty tax.” Low-income citizens have fewer ways to avoid the draft. By contrast, wealthier Russians can use legal methods — such as enrolling in higher education or obtaining medical exemptions, often facilitated by private clinics and legal consultants. Others turn to illegal strategies: bribery, forged documents, or buying draft exemptions. The poor, by and large, lack access to such options. Conscripts also face pressure to sign contracts while in service. Once they do they can be deployed to the front, and the contract becomes open-ended.

Economic inequality plays a key role in recruitment incentives. In Moscow, the government offers more than 5 million rubles (about USD $55,000) for a one-year military contract — an amount that might appeal even to middle-class families. But for residents of poorer regions, the payment is life-changing. In the Republic of Mari El, for instance, the subsistence level is just 14,823 rubles a month, and the average salary barely exceeds 25,000 rubles. There, a signing bonus of 3 million rubles equates to more than a decade’s worth of wages.

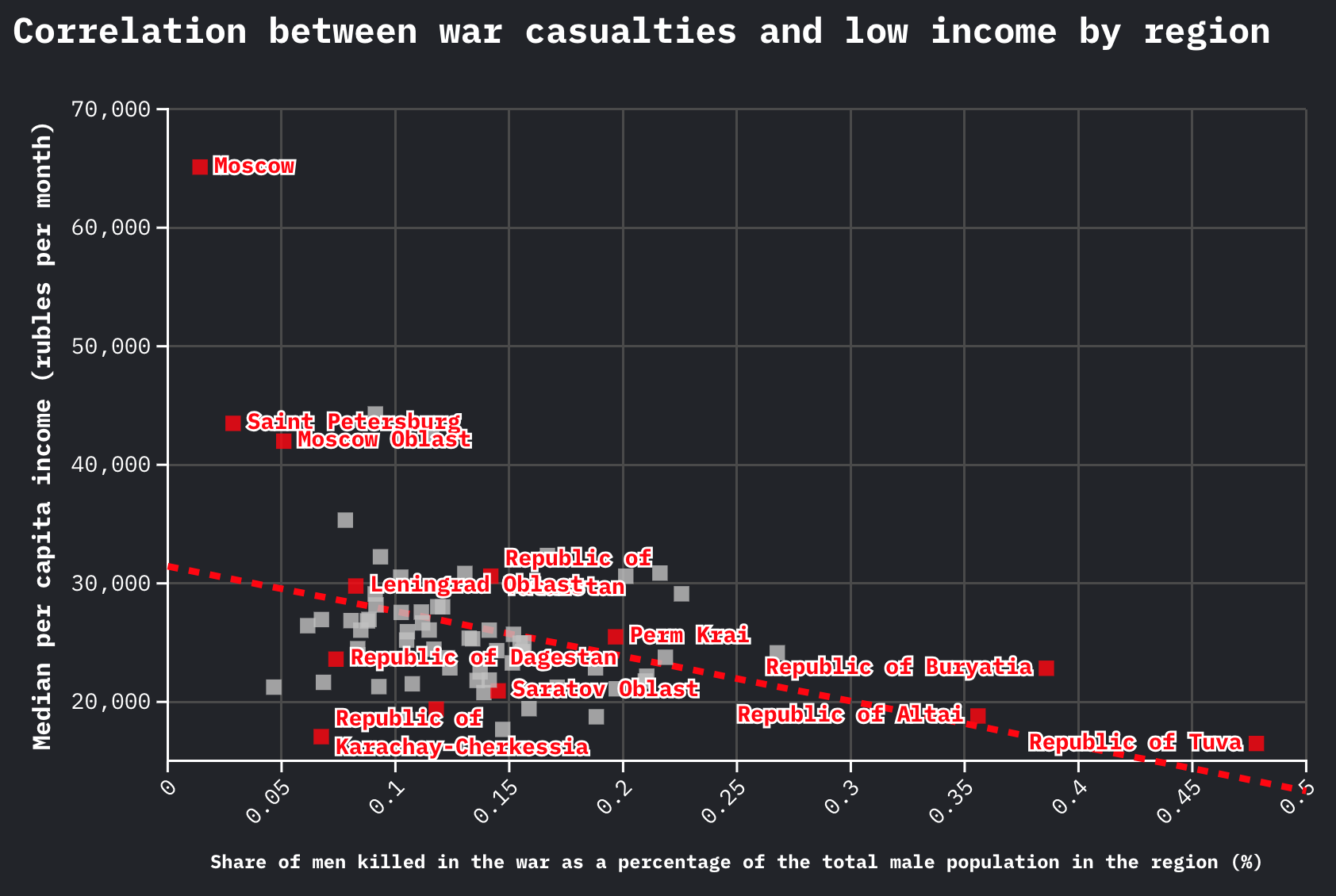

It has become increasingly clear that Russia is exploiting regional poverty to staff its military. The lower a region’s median income, the higher its share of war casualties. Leading the fatality rate are Tyva, Buryatia, and Altai — some of the country’s poorest regions. In contrast, Moscow, with its significantly higher living standards, records far fewer losses despite its large population.

Mobilization has affected Russia’s regions unevenly, compounding existing economic inequality with disproportionate human losses. Unlike contract military service, where financial incentives may influence enlistment, mobilization is compulsory — but its impact varies widely depending on location. The exact number of people mobilized from each region is unknown as the federal government has not released official statistics. The scale of mobilization can only be inferred indirectly — primarily through regional casualty data.

Local political leadership plays a significant role in shaping how federal mobilization decrees are enforced. Some regional authorities exercise substantial autonomy, and much depends on the personality and political leverage of the individual in charge. The Chechen Republic, led by Ramzan Kadyrov since 2007, offers a clear example of how local elites can influence the application of federal mandates. Kadyrov is a key Kremlin ally, credited with maintaining postwar stability in the republic after the Second Chechen War. His political verticality has made him indispensable to Moscow, allowing for a relationship built more on negotiation than compliance.

On September 23, 2022, Kadyrov declared that mobilization in Chechnya was complete, claiming the republic had fulfilled its quota “by 254%.” His announcement came while federal mobilization efforts were still ongoing, demonstrating his ability to deviate from central policy. As a politically autonomous leader, Kadyrov has influence not only over Chechnya but over federal decisions themselves.

A similar dynamic exists in Moscow, where Mayor Sergei Sobyanin — who has led the city since 2010 — also plays a strategic role for the Kremlin. Sobyanin maintains political stability in the capital and is known for his loyalty to the federal government. Authorities trust that protest movements in Moscow will be swiftly neutralized. In 2019, for instance, demonstrators protesting the disqualification of independent candidates from the Moscow City Duma elections were effectively dispersed, with hundreds detained. Sobyanin has cultivated an image as a competent technocrat, a reputation that has earned him a degree of political flexibility. On October 17, 2022, he had the privilege of announcing the end of partial mobilization in Moscow — despite the fact that the federal decree remained in effect until the end of the month. The disparity in military casualties between Chechnya and Tyva underscores mobilization’s political dimension. Despite similar economic conditions, the death rate in Chechnya is 12 times lower than in Tyva. This is largely because Kadyrov, as a crucial figure for the Kremlin, has greater leeway to diverge from federal orders. The central government prefers to negotiate with him rather than issue directives — exacerbating the regional imbalance in wartime fatalities.

Inequality and ethnic minorities: The cases of Perm Krai and the Chuvash Republic

While political factors shape disparities between regions at the federal level, economic inequality plays a greater role within individual regions. Economic conditions can vary dramatically from district to district, and this variation directly affects mobilization patterns and wartime losses.

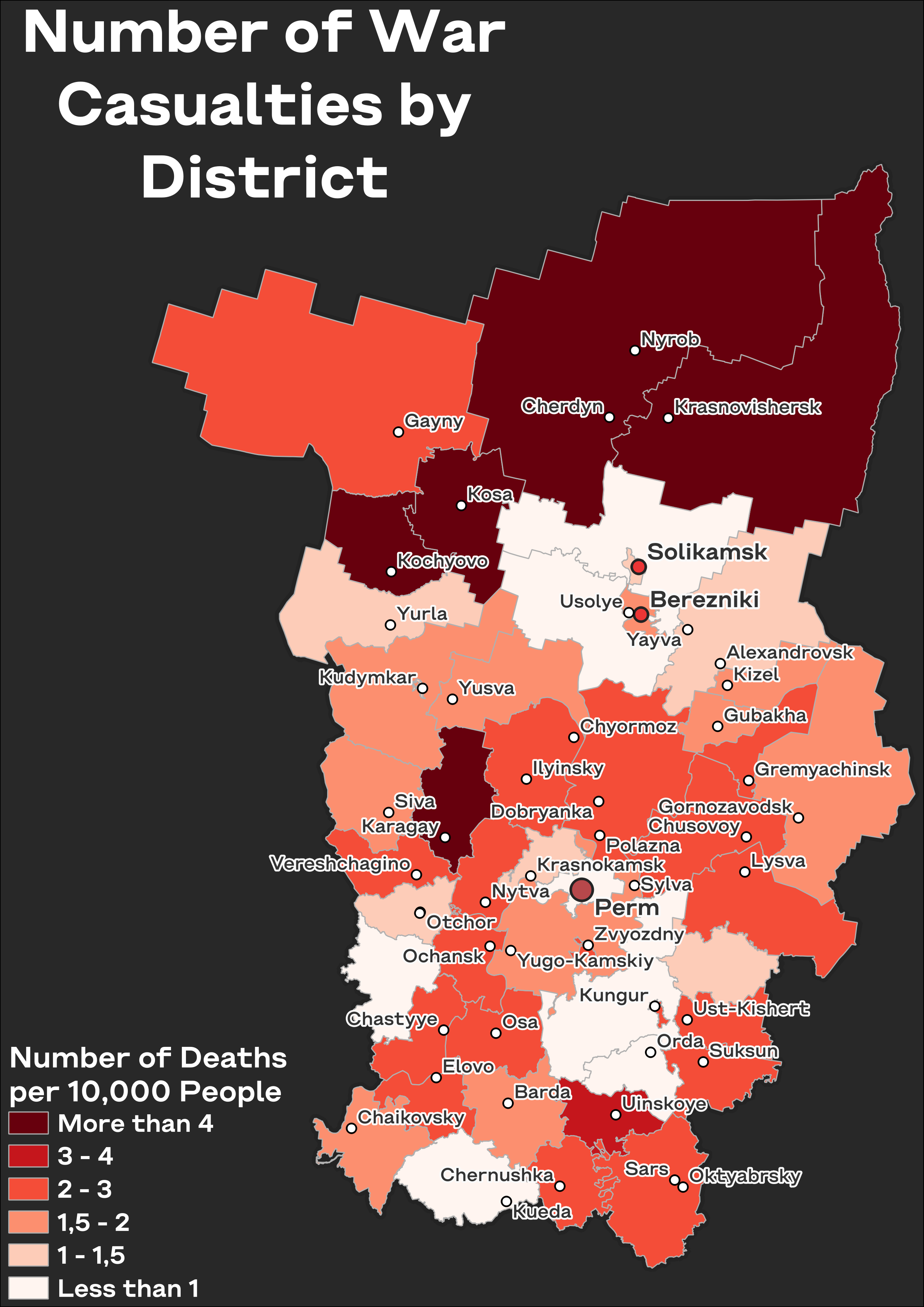

Take Perm Krai, for example — a region dominated by one large city. The city of Perm accounts for nearly 40 percent of the region’s total population, and not surprisingly, leads in the absolute number of war fatalities. However, when fatalities are measured as a share of the population, remote rural districts emerge as the most affected. A 2023 report by Perm 36.6, a local investigative project, documented regional wartime deaths. After the first year of the war, it became evident that Perm itself had a relatively low proportion of fatalities compared to outlying areas.

Perm 36.6 generously shared data with us covering two years of the war. The distribution has shifted slightly: Perm now stands out even more sharply from the rest of the region as a city with comparatively low losses.

Trends across the wider region are also revealing: over time, the highest mortality rates have shifted from the north to the northwest of Perm Krai, with the sample size of reported deaths more than doubling in just two years.

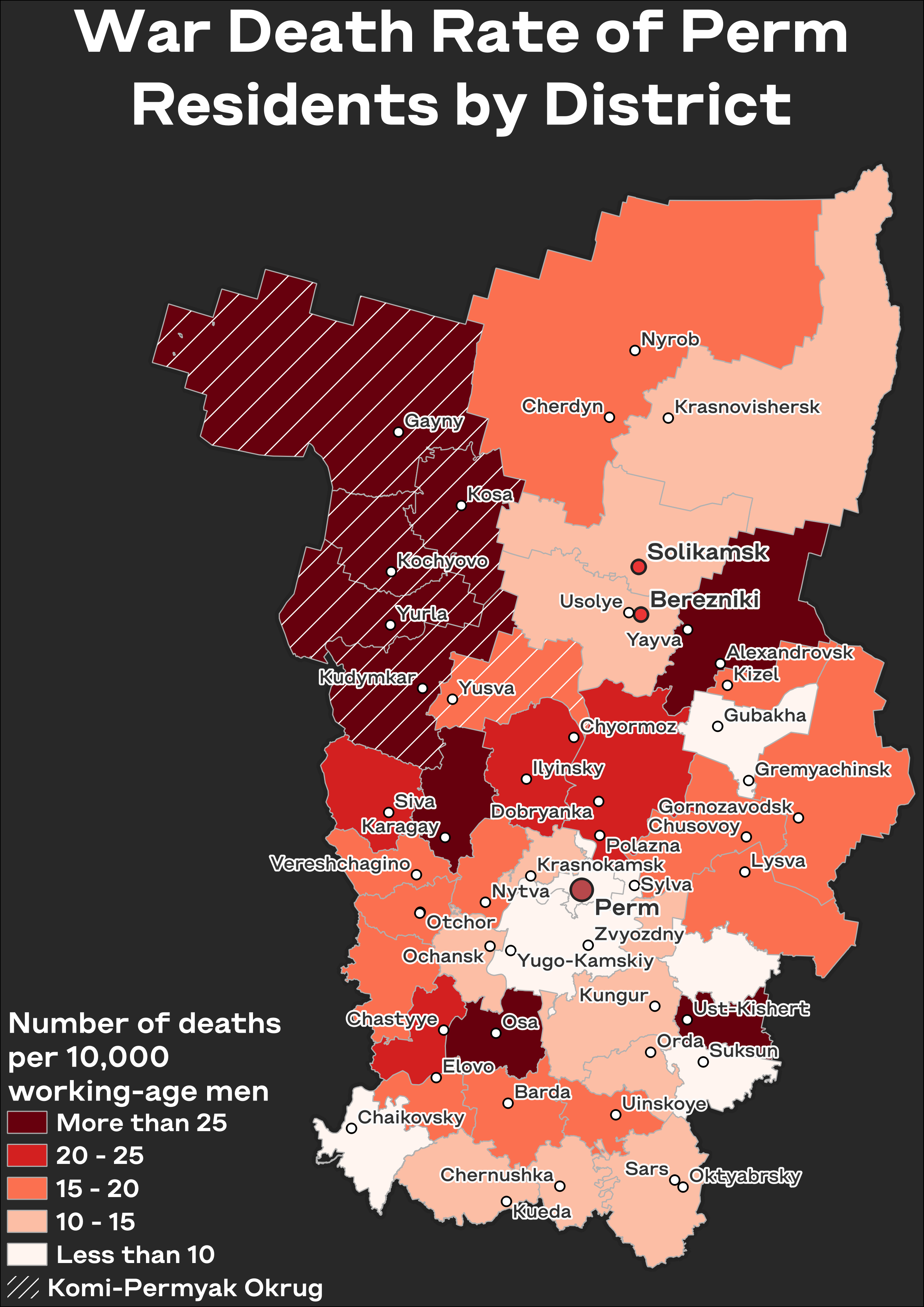

This may be due to the region’s historical and ethnic peculiarities. Following a regional referendum In 2005, the Komi-Permyak Autonomous Okrug was merged with Perm Oblast to form Perm Krai. While the merger provoked little public dissent within Russia, it sparked protests among Finno-Ugric activists abroad — most notably a rally outside the Russian embassy in Helsinki, where demonstrators warned of the impending cultural assimilation of the Permian Komi people.

Their fears appear to have been justified. Despite comprising the majority population of the former autonomous district, the Permian Komi have seen a drastic demographic decline since the merger. In 2002 their population was estimated at 235,000. By 2010, that number had dropped to 94,000. As of 2023 slightly more than 50,000 people remain — a sevenfold decrease in just over two decades.

The highest death rates are concentrated in rural districts and small settlements, reinforcing the hypothesis that impoverished areas are more heavily targeted for mobilization, or that residents in these areas are more likely to enlist voluntarily due to economic hardship. Regional authorities often prioritize rural conscription to avoid fueling unrest in urban centers. In national republics, where indigenous communities tend to reside in villages, ethnic minorities are often drafted first. While the extent of this practice is difficult to verify, casualty data strongly suggest that ethnic minorities in Perm Krai have borne a disproportionate share of the war’s human cost.

The correlation between income and casualty rates in Perm Krai is statistically significant. Areas with the lowest average wages show the highest death rates. The correlation coefficient between average district wages and the percentage of men killed is -0.37, indicating a clear inverse relationship. In some cases, men from large families — including fathers with multiple children — have been mobilized in violation of federal guidelines, particularly in the Komi-Permyak District.

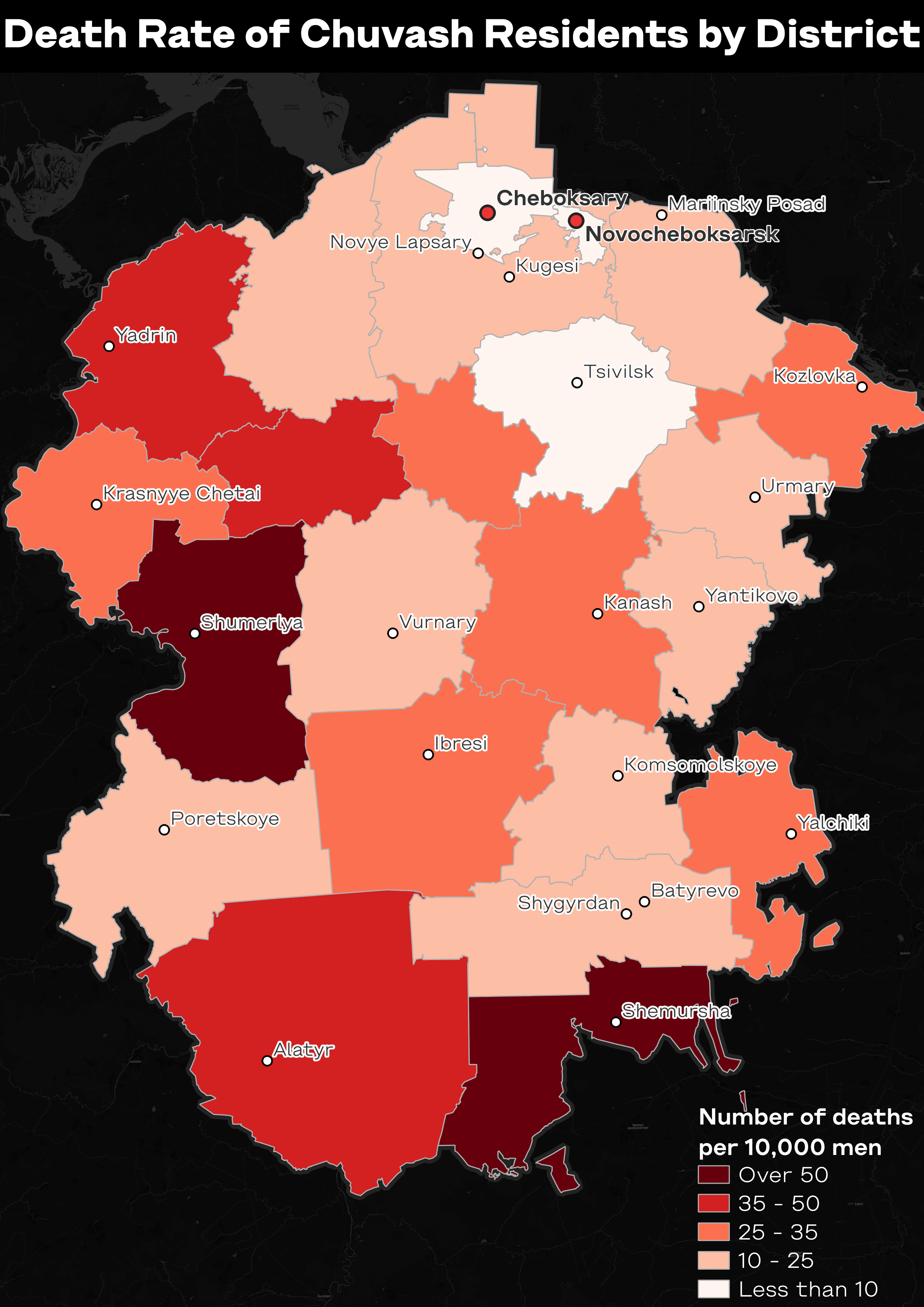

To further test this pattern, researchers expanded their analysis to the Chuvash Republic. Independent journalists from Angry Chuvashia shared data on regional war casualties as of November 2024. The correlation between income and fatality rates in Chuvashia was weaker (-0.27) than in Perm Krai, but the overall trend held: the lower the official wage in a district, the higher the death toll.

While these findings are limited by available data, they consistently support the hypothesis that poverty and marginalization are key predictors of who bears the human cost of war. Further research is needed, but the emerging picture is clear: Russia’s poorest and most remote communities continue to pay the highest price.

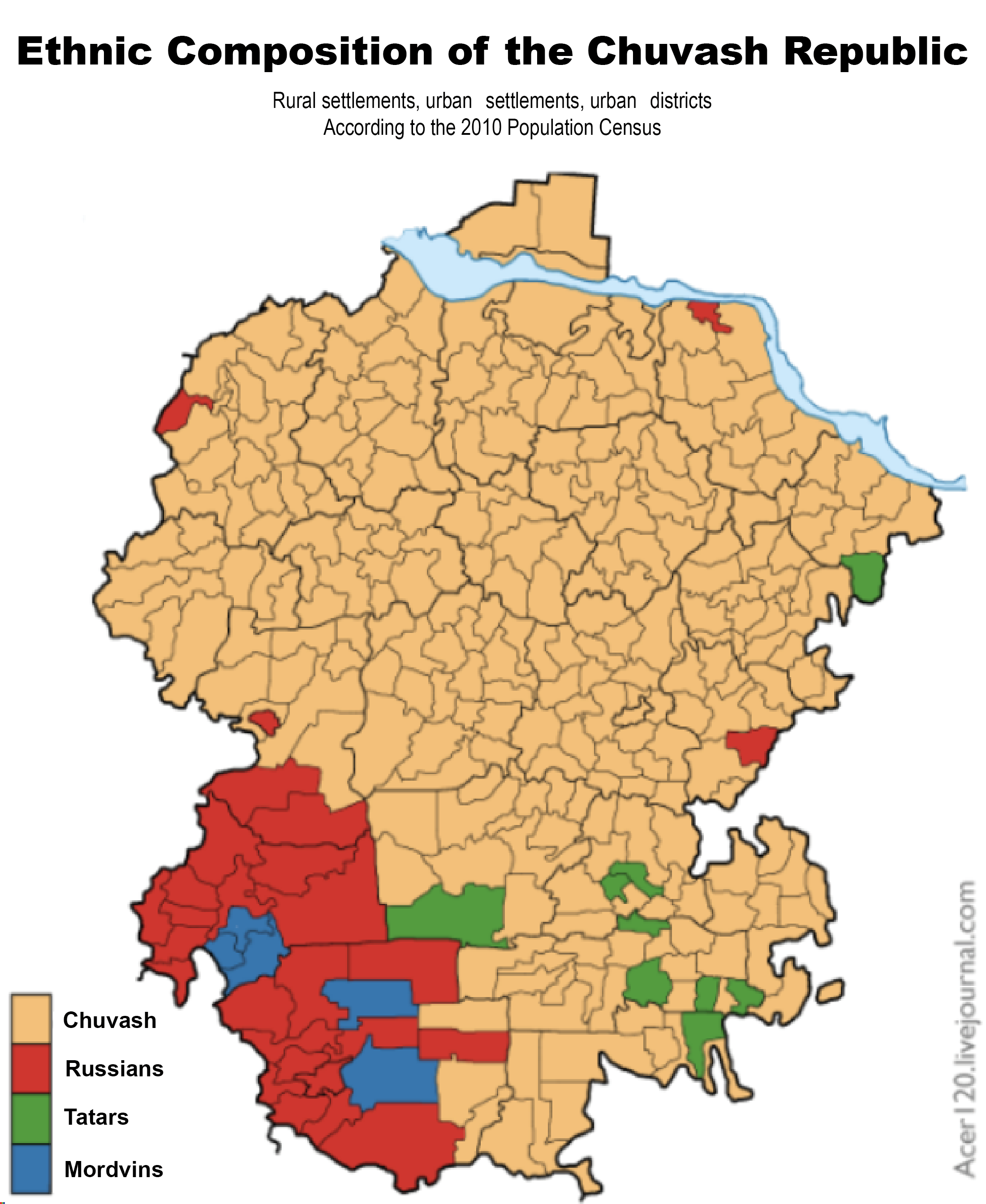

When examining a region through the lens of ethnic composition, it is clear that the southwest of the Chuvash Republic is predominantly Russian. This is evident from maps based on the 2010 census. However, when this demographic map is compared with data on war fatalities, no clear correlation emerges between the ethnic composition and the percentage of male deaths — unlike in Perm Krai. This difference is likely due to the fact that the districts of the former Komi-Permyak Autonomous Okrug are among the poorest in the entire region.

In other words, economic conditions appear to have a greater influence on wartime mortality than ethnic background.

Conclusion

Poverty inevitably drives people to seek any means of survival. When your financial situation is dire, it becomes far easier to be coerced into going to war. Many poor republics in Russia are sustained not through strategic investment or industrial development but through subsidies. There is little effort to attract major businesses or develop modern industries that could provide stable, long-term budget revenues. If such efforts were made, local authorities might be able to engage in actual planning and foster development. But neither local officials — functioning more as appointed stewards than autonomous leaders — nor the federal government — acting as a metropolitan center — appear to have any interest in such outcomes.

This state of affairs is no accident. The centralization of political authority and the redistribution of financial resources in favor of Moscow have entrenched peripheral regions’ dependence on the state center. These regions are deprived of meaningful tools for economic growth. Their budgets rely not on local industry or investment but on top-down subsidies. This structure makes regional governments more controllable, and it leaves local populations increasingly vulnerable to external shocks — including military mobilization.

Russia remains a country defined by stark inequality between the center and the periphery. The regions weakened in past decades continue to lack the resources needed for survival or meaningful development. Chronic poverty, depressed incomes, and economic isolation have turned these areas into a reservoir of human capital for the central government, with their economic survival tethered entirely to decisions made in Moscow.

____________

This analysis uses data on median per capita income and the size of the male population by region as of early 2022. Data on wartime fatalities was sourced from Mediazona. The share of male deaths was calculated by dividing the number of confirmed fatalities by the total male population in each region and multiplying by 100.

The study excludes several far northern regions — Kamchatka Krai, the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Sakhalin Oblast, Magadan Oblast, Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, and Nenets Autonomous Okrug — due to their significantly higher average wages driven by geographic and logistical challenges. The cost of goods and services in these areas is difficult to compare meaningfully with the rest of the country due to limited and inconsistent regional statistics.

Chechnya and Ingushetia were also excluded, but for a different reason. According to researchers, these regions have significantly inflated population figures. As a result, the actual fatality rate may be 1.5 to 2 times higher than official estimates suggest.