CRT YOU NEED

A sketch from 1877 illustrating the landing of the Pilgrims, by artist Albert Bobbett.

November 25, 2024

Every November, numerous articles recount the arrival of 17th-century English Pilgrims and Puritans and their quest for religious freedom. Stories are told about the founding of Massachusetts Bay Colony and the celebration of the first Thanksgiving feast.

In the popular mind, the two groups are synonymous. In the story of the quintessential American holiday, they have become inseparable protagonists in the story of the origins.

But as a scholar of both English and American history, I know there are significant differences between the two groups. Nowhere is this more telling than in their respective religious beliefs and treatment of Native Americans.

Every November, numerous articles recount the arrival of 17th-century English Pilgrims and Puritans and their quest for religious freedom. Stories are told about the founding of Massachusetts Bay Colony and the celebration of the first Thanksgiving feast.

In the popular mind, the two groups are synonymous. In the story of the quintessential American holiday, they have become inseparable protagonists in the story of the origins.

But as a scholar of both English and American history, I know there are significant differences between the two groups. Nowhere is this more telling than in their respective religious beliefs and treatment of Native Americans.

Where did the Pilgrims come from?

Pilgrims arose from the English Puritan movement that originated in the 1570s. Puritans wanted the English Protestant Reformation to go further. They wished to rid the Church of England of “popish” – that is, Catholic – elements like bishops and kneeling at services.

Each Puritan congregation made its own covenant with God and answered only to the Almighty. Puritans looked for evidence of a “godly life,” meaning evidence of their own prosperous and virtuous lives that would assure them of eternal salvation. They saw worldly success as a sign, though not necessarily a guarantee, of eventual entrance into heaven.

After 1605, some Puritans became what scholar Nathaniel Philbrick calls “Puritans with a vengeance.” They embraced “extreme separatism,” removing themselves from England and its corrupt church.

These Puritans would soon become “Pilgrims” – literally meaning that they would be prepared to travel to distant lands to worship as they pleased.

In 1608, a group of 100 Pilgrims sailed to Leiden, Holland and became a separate church living and worshipping by themselves.

They were not satisfied in Leiden. Believing Holland also to be sinful and ungodly, they decided in 1620 to venture to the New World in a leaky vessel called the Mayflower. Fewer than 40 Pilgrims joined 65 nonbelievers, whom the Pilgrims dubbed “strangers,” in making the arduous journey to what would be called Plymouth Colony.

Hardship, survival and Thanksgiving in America

Most Americans know that more than half of the Mayflower’s passengers died the first harsh winter of 1620-21. The fragile colony survived only with the assistance of Native Americans – most famously Squanto. To commemorate, not celebrate, their survival, Pilgrims joined Native Americans in a grand meal during the autumn of 1621.

But for the Pilgrims, what we today know as Thanksgiving was not a feast; rather, it was a spiritual devotion. Thanksgiving was a solemn and not a celebratory occasion. It was not a holiday.

Still, Plymouth was dominated by the 65 strangers, who were largely disinterested in what Pilgrims saw as urgent questions of their own eternal salvation.

There were few Protestant clerics among the Pilgrims, and in few short years, they found themselves to be what historian Mark Peterson calls “spiritual orphans.” Lay Pilgrims like William Brewster conducted services, but they were unable to administer Puritan sacraments.

Pilgrims and Native Americans in the 1620s

At the same time, Pilgrims did not actively seek the conversion of Native Americans. According to scholars like Philbrick, English author Rebecca Fraser and Peterson, the Pilgrims appreciated and respected the intellect and common humanity of Native Americans.

An early example of Pilgrim respect for the humanity of Native Americans came from the pen of Edward Winslow. Winslow was one of the chief Pilgrim founders of Plymouth. In 1622, just two years after the Pilgrims’ arrival, he published in the mother country the first book about life in New England, “Mourt’s Relation.”

While opining that Native Americans “are a people without any religion or knowledge of God,” he nevertheless praised them for being “very trusty, quick of apprehension, ripe witted, just.”

Winslow added that “we have found the Indians very faithful in their covenant of peace with us; very loving. … we often go to them, and they come to us; some of us have been fifty miles by land in the country with them.”

In Winslow’s second published book, “Good Newes from New England (1624),” he recounted at length nursing the Wampanoag leader Massasoit as he lay dying, even to the point of spoon-feeding him chicken broth.Fraser calls this episode “very tender.”

The Puritan exodus from England

Puritans barricading their house against Indians. Artist Albert Bobbett.

The Print Collector/ Hudson Archives via Getty Images

The thousands of non-Pilgrim Puritans who remained behind and struggled in England would not share Winslow’s views. They were more concerned with what they saw as their own divine mission in America.

After 1628, dominant Puritan ministers clashed openly with the English Church and, more ominously, with King Charles I and Bishop of London – later Archbishop of Canterbury – William Laud.

So, hundreds and then thousands of Puritans made the momentous decision to leave England behind and follow the tiny band of Pilgrims to America. These Puritans never considered themselves separatists, though. Following what they were confident would be the ultimate triumph of the Puritans who remained in the mother country, they would return to help govern England.

The American Puritans of the 1630s and beyond were more ardent, and nervous about salvation, than the Pilgrims of the 1620s. Puritans tightly regulated both church and society and demanded proof of godly status, meaning evidence of a prosperous and virtuous life leading to eternal salvation. They were also acutely aware of that divine-sent mission to the New World.

Puritans believed they must seek out and convert Native Americans so as to “raise them to godliness.” Tens of thousands of Puritans therefore poured into Massachusetts Bay Colony in what became known as the “Great Migration.” By 1645, they already surrounded and would in time absorb the remnants of Plymouth Colony.

The thousands of non-Pilgrim Puritans who remained behind and struggled in England would not share Winslow’s views. They were more concerned with what they saw as their own divine mission in America.

After 1628, dominant Puritan ministers clashed openly with the English Church and, more ominously, with King Charles I and Bishop of London – later Archbishop of Canterbury – William Laud.

So, hundreds and then thousands of Puritans made the momentous decision to leave England behind and follow the tiny band of Pilgrims to America. These Puritans never considered themselves separatists, though. Following what they were confident would be the ultimate triumph of the Puritans who remained in the mother country, they would return to help govern England.

The American Puritans of the 1630s and beyond were more ardent, and nervous about salvation, than the Pilgrims of the 1620s. Puritans tightly regulated both church and society and demanded proof of godly status, meaning evidence of a prosperous and virtuous life leading to eternal salvation. They were also acutely aware of that divine-sent mission to the New World.

Puritans believed they must seek out and convert Native Americans so as to “raise them to godliness.” Tens of thousands of Puritans therefore poured into Massachusetts Bay Colony in what became known as the “Great Migration.” By 1645, they already surrounded and would in time absorb the remnants of Plymouth Colony.

Puritans and Native Americans in the 1630s and beyond

Dominated by hundreds of Puritan clergy, Massachusetts Bay Colony was all about emigration, expansion and evangelization during this period.

As early as 1651, Puritan evangelists like Thomas Mayhew had converted 199 Native Americans labeled by the Puritans as “praying Indians.”

For those Native Americans who converted to Christianity and prayed with the Puritans, there existed an uneasy harmony with Europeans. For those who resisted what the Puritans saw as “God’s mission,” there was harsh treatment – and often death.

But even for those who succumbed to the Puritans’ evangelization, their culture and destiny changed dramatically and unalterably.

War with Native Americans

A devastating outcome of Puritan cultural dominance and prejudice was King Philip’s War in 1675-76. Massachusetts Bay Colony feared that Wampanoag chief Metacom – labeled by Puritans “King Philip” – planned to attack English settlements throughout New England in retaliation for the murder of “praying Indian” John Sassamon.

That suspicion mushroomed into a 14-month, all-out war between colonists and Native Americans over land, religion and control of the region’s economy. The conflict would prove to be one of the bloodiest per capita in all of American history.

By September 1676, thousands of Native Americans had been killed, with hundreds of others sold into servitude and slavery. King Philip’s War set an ominous precedent for Anglo-Native American relations throughout most of North America for centuries to come.

The Pilgrims’ true legacy

So, Puritans and Pilgrims came out of the same religious culture of 1570s England. They diverged in the early 1600s, but wound up 70 years later being one and the same in the New World.

In between, Pilgrim separatists sailed to Plymouth, survived a terrible first winter and convened a robust harvest-time meal with Native Americans. Traditionally, the Thanksgiving holiday calls to mind those first settlers’ courage and tenacity.

However, the humanity that Pilgrims like Edward Winslow showed toward the Native Americans they encountered was lamentably and tragically not shared by the Puritan colonists who followed them. Therefore, the ultimate legacy of Thanksgiving is and will remain mixed.

Michael Carrafiello, Professor of History, Miami University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

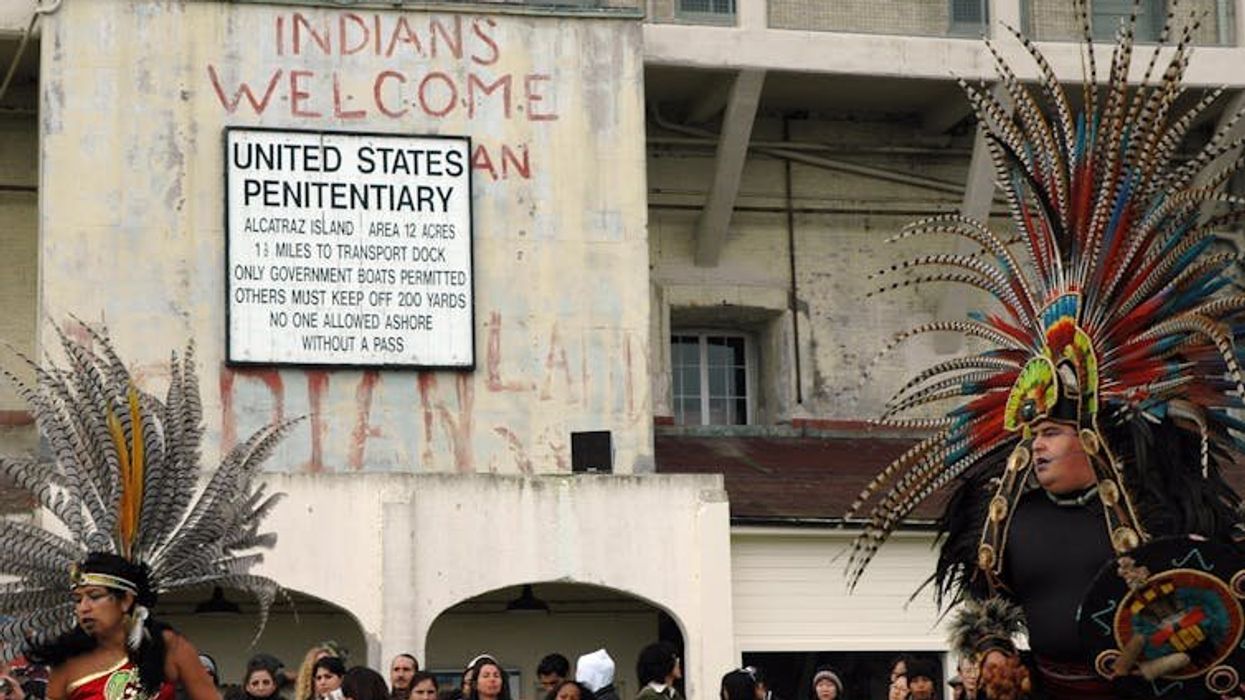

Unthanksgiving Day: A annual celebration of Indigenous resistance to colonialism at Alcatraz

The Teo Kali, an Aztec cultural group, participates in a sunrise “Unthanksgiving Day” ceremony with Native Americans on Nov. 24, 2005, on Alcatraz Island. Kara Andrade/AFP via Getty Images

The Conversation

November 24, 2024

Each year on the fourth Thursday of November, when many people start to take stock of the marathon day of cooking ahead, Indigenous people from diverse tribes and nations gather at sunrise in San Francisco Bay.

Their gathering is meant to mark a different occasion – the Indigenous People’s Thanksgiving Sunrise Ceremony, an annual celebration that spotlights 500 years of Native resistance to colonialism in what was dubbed the “New World.” Held on the traditional lands of the Ohlone people, the gathering is a call for remembrance and for future action for Indigenous people and their allies.

As a scholar of Indigenous literary and cultural studies, I introduce my students to the long and enduring history of Indigenous peoples’ pushback against settler violence. The origins of this sunrise event are a particularly compelling example that stem from a pivotal moment of Indigenous activism: the Native American occupation of Alcatraz Island, a 19-month-long takeover that began in 1969.

Each year on the fourth Thursday of November, when many people start to take stock of the marathon day of cooking ahead, Indigenous people from diverse tribes and nations gather at sunrise in San Francisco Bay.

Their gathering is meant to mark a different occasion – the Indigenous People’s Thanksgiving Sunrise Ceremony, an annual celebration that spotlights 500 years of Native resistance to colonialism in what was dubbed the “New World.” Held on the traditional lands of the Ohlone people, the gathering is a call for remembrance and for future action for Indigenous people and their allies.

As a scholar of Indigenous literary and cultural studies, I introduce my students to the long and enduring history of Indigenous peoples’ pushback against settler violence. The origins of this sunrise event are a particularly compelling example that stem from a pivotal moment of Indigenous activism: the Native American occupation of Alcatraz Island, a 19-month-long takeover that began in 1969.

Reclaiming of Alcatraz Island

On Nov. 20, 1969, led by Indigenous organizers Richard Oakes (Mohawk) and LaNada War Jack (Shoshone Bannock), roughly 100 activists who called themselves “Indians of All Tribes,” or IAT, traveled by charter boat across San Francisco Bay to reclaim the island for Native peoples. Multiple groups had done smaller demonstrations on Alcatraz in previous years, but this group planned to stay, and it maintained its presence there until June 1971.

Before this occupation, Alcatraz Island had served as a military prison and then a federal penitentiary. U.S. Prison Alcatraz was decommissioned in 1963 because of the high cost of its upkeep, and it was essentially left abandoned. In November 1969, after a fire destroyed the American Indian Center in San Francisco, local Indigenous activists were looking for a new place where urban Natives could gather and access resources, such as legal assistance and educational opportunities, and Alcatraz Island fit the bill.

Citing a federal law that stated that “unused or retired federal lands will be returned to Native American tribes,” Oakes’ group settled in to live on “The Rock.” They elected a council and established a school, a medical center and other necessary infrastructure. They even had a pirate radio show called “Radio Free Alcatraz,” hosted by Santee Dakota poet John Trudell.

The IAT did offer – albeit satirically – to purchase the island back, proposing in the 1969 proclamation “twenty-four dollars (US$24) in glass beads and red cloth, a precedent set by the white man’s purchase of a similar island about 300 years ago,” referring to the purchase of Manhattan Island by the Dutch in 1626.

On behalf of IAT, Oakes sent the following message to the regional office San Francisco office of the Department of the Interior shortly after they arrived:

“The choice now lies with the leaders of the American government – to use violence upon us as before to remove us from our Great Spirit’s land, or to institute a real change in its dealing with the American Indian … We and all other oppressed peoples would welcome spectacle of proof before the world of your title by genocide. Nevertheless, we seek peace.”

After 19 months, the occupation ultimately succumbed to internal and external pressures. Oakes left the island after a family tragedy, and many members of the original group returned to school, leaving a gap in leadership. Moreover, the government cut off water and electricity to the island, and a mysterious fire destroyed several buildings, with the Indigenous occupiers and government officials pointing the blame at one another.

By June 1971, President Richard Nixon was ready to intervene and ordered federal agents to remove the few remaining occupiers. The occupation was over, but it helped spark an Indigenous political revitalization that continues today. It also pushed Nixon to put an official end to the “termination era,” a legislative effort geared toward ending the federal government’s responsibility to Native nations, as articulated in treaties and formal agreements.

Solidarity at sunrise

In 1975, “Unthanksgiving Day” was established to both mark the occupation and advocate for Indigenous self-determination. For many participants, Unthanksgiving Day was also a reiteration of the original declaration released by IAT, which called on the U.S. to acknowledge the impacts of 500 years of genocide against Indigenous people.

These days, the event is conducted by the International Indian Treaty Council and is largely referred to as the Indigenous Peoples Thanksgiving Sunrise Gathering. Sunrise ceremony on Alcatraz celebrating Indigenous Peoples Day.

Participants meet on Pier 33 in San Francisco before dawn and board boats to Alcatraz Island, bringing Native peoples and allies together in the place that symbolizes a key moment in the long history of Indigenous resistance.

At dawn, in the courtyard of what was once a federal penitentiary, sunrise ceremonies are conducted to “give thanks for our lives, for the beatings of our heart,” said Andrea Carmen, a member of Yaqui Nation and executive director of the International Indian Treaty Council, at the 2018 gathering.

Songs and dances from various tribal nations are performed in prayer and as acts of collective solidarity. At the same gathering, Lakota Harden, who is a Minnecoujou/ Yankton Lakota and HoChunk community leader and organizer, emphasized that “those voices and the medicine in those songs are centuries old and our ancestors come and they appreciate being acknowledged when the sun comes up.” Through the sharing of song and dance, they enact culturally resonant resistance against the erasure of Native peoples from these lands.

The Indigenous Peoples Thanksgiving Sunrise Gathering also gives people the chance to bring greater community awareness to current struggles facing Indigenous people across the globe. These include the intensifying impacts of climate change, the widespread violence against Native women, children and two-spirit individuals, and ongoing threats to the integrity of their ancestral homelands.

Resistance beyond The Rock

Indigenous Peoples Thanksgiving Sunrise Gathering lands near the end of Native American Heritage Month, which is dedicated to celebrating the vast and diverse Indigenous nations and tribes that exist in the United States. Professor Jamie Folsom, who is Choctaw, describes this month as a chance to “present who we are today … (and) to present our issues in our own voices and to tell our own stories.”

The people who will meet on Pier 33 on the fourth Thursday of November continue this story of Indigenous political action on the Rock and, by extension, in North America. The more than 50-year history of this gathering is a testament to the endurance of the original message from Oakes and Indians of All Tribes. It is also part of a larger network of resistance movements being led by Native peoples, particularly young people.

As Harden says, the next generation is asking for change. “They’re standing up and saying we’ve had enough. And our future generations will make sure that things change.”

Shannon Toll, Associate Professor of Indigenous Literatures, University of Dayton

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

At dawn, in the courtyard of what was once a federal penitentiary, sunrise ceremonies are conducted to “give thanks for our lives, for the beatings of our heart,” said Andrea Carmen, a member of Yaqui Nation and executive director of the International Indian Treaty Council, at the 2018 gathering.

Songs and dances from various tribal nations are performed in prayer and as acts of collective solidarity. At the same gathering, Lakota Harden, who is a Minnecoujou/ Yankton Lakota and HoChunk community leader and organizer, emphasized that “those voices and the medicine in those songs are centuries old and our ancestors come and they appreciate being acknowledged when the sun comes up.” Through the sharing of song and dance, they enact culturally resonant resistance against the erasure of Native peoples from these lands.

The Indigenous Peoples Thanksgiving Sunrise Gathering also gives people the chance to bring greater community awareness to current struggles facing Indigenous people across the globe. These include the intensifying impacts of climate change, the widespread violence against Native women, children and two-spirit individuals, and ongoing threats to the integrity of their ancestral homelands.

Resistance beyond The Rock

Indigenous Peoples Thanksgiving Sunrise Gathering lands near the end of Native American Heritage Month, which is dedicated to celebrating the vast and diverse Indigenous nations and tribes that exist in the United States. Professor Jamie Folsom, who is Choctaw, describes this month as a chance to “present who we are today … (and) to present our issues in our own voices and to tell our own stories.”

The people who will meet on Pier 33 on the fourth Thursday of November continue this story of Indigenous political action on the Rock and, by extension, in North America. The more than 50-year history of this gathering is a testament to the endurance of the original message from Oakes and Indians of All Tribes. It is also part of a larger network of resistance movements being led by Native peoples, particularly young people.

As Harden says, the next generation is asking for change. “They’re standing up and saying we’ve had enough. And our future generations will make sure that things change.”

Shannon Toll, Associate Professor of Indigenous Literatures, University of Dayton

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment