Will Sharks survive extinction this time?

In Marsa Alam, it was the first time that Haitham Obaid tried diving to see sharks in the flesh; needless to say, he felt scared. After some time, the diver’s feelings shifted to fascination and admiration, as he accompanied dozens of tourists who came from all over the world to see sharks in Egypt.

He was assured that they were peaceful creatures as long as no one attacks them.

“I got angry when I realised that people kill them and waste their environmental and economic value to make a soup dish,” he went on to say.

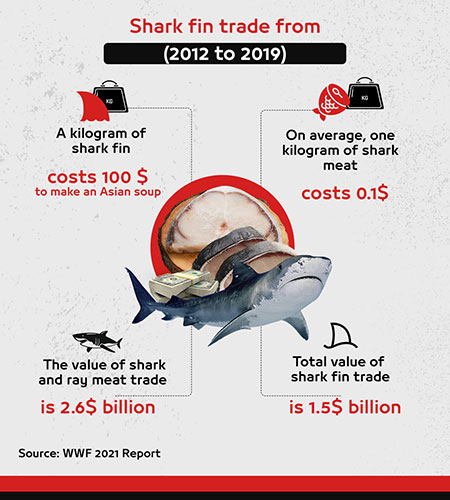

A thousand years ago in China, someone came up with a shark fin soup, and since then, it has become one of the most expensive dishes in the world.

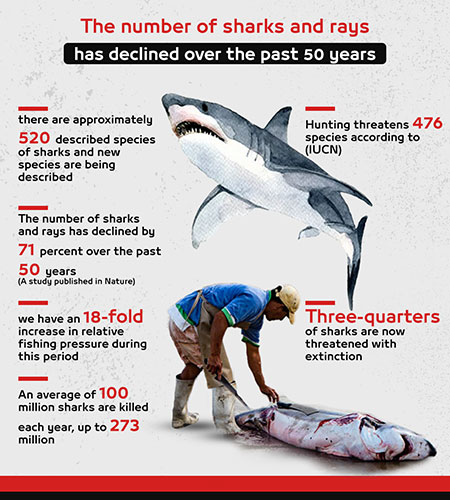

For this particular dish — and other reasons — 100 million sharks are killed every year according to recent surveys, either by hunting to harvest their components or finning them then throwing them back into the sea to bleed to death.

When you hear the word “shark”, all you think about is the image of this fierce giant creature that smells your fear and can shred you to pieces, but when you learn how this creature is followed by death in different ways, you’ll end up sympathising with it.

Sharks have existed since 450 million years ago; they were classified as cartilaginous fish. Years later, scientists discovered different species of sharks, and now they have recorded around 520 species of the marine animal, with more still being discovered every once in a while.

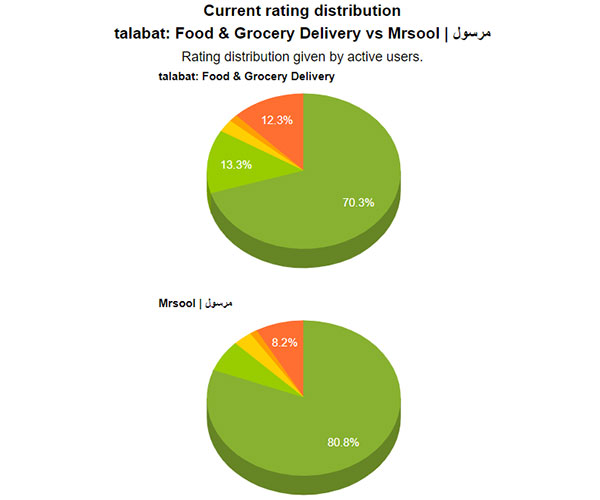

In the last 50 years, targeting sharks and rays has increased, leading to a decrease in their numbers by 70 percent and endangering them with extinction. How did we reach this point?

Why is the world hunting down sharks?

Basically, the world primarily trades in two shark components: the meat, which has a small economic value compared to the more profitable component, which is the fins. Currently, fins can cost up to USD 100 per kg, while their meat runs for about USD 0.1 per kg.

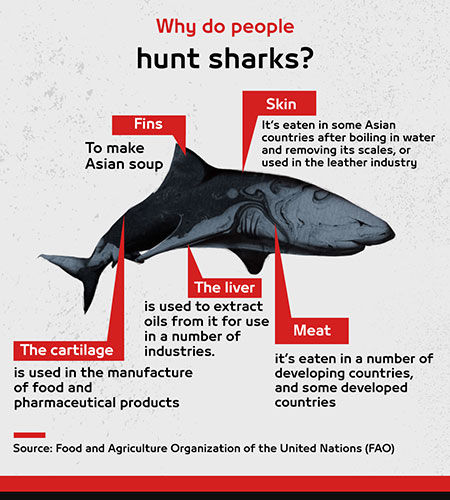

Fins and meat, however, are not the only parts of sharks humans are after, as they use their skin, cartilage, and liver as well.

Many Asian and Oceania countries eat shark skin after boiling it in water and removing its scales.

Shark cartilage is also used in the food industry sometimes and is a commonly used component in the manufacturing of pharmaceutical products, whereas the oils from the liver are used in a number of industries, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation.

Sharks at the top of the food chain

Marine life follows a precise eco system in obtaining food, and its organisms are classified according to their position in the levels of the food chain or the so-called “food pyramid”, so each species feeds on fish that are located at a lower level in this pyramid.

Sharks are at the top of this food chain, according to Mahmoud El-Hanafy, a professor of marine environment at the Suez Canal University, saying “sharks are a vital indication for marine environment balance. They prey on genetically weak or sick fish, hence keeping the balance in the lower levels of the food chain in terms of numbers and species. They also enhance the purity of genetic strength in existing fish.”

“Depletion in sharks’ numbers leads to an increase in fish lower than them in the pyramid, resulting in an imbalance in the whole food chain, as each level plays a certain designated role, thus we lose this biodiversity, and the efficiency of the ecosystem is affected.”

Why is it difficult to save shark species?

Along with endangering sharks, saving them is just as complicated and difficult, for it might take these creatures decades to repopulate.

“Sharks reproduce slowly and have low fertility levels, meaning they produce not more than tens of pups, which is nothing compared to other fishes that produce maybe a million eggs; thus, shark communities have a limited ability to repopulate and take a long period of time to recover and restore their numbers,” says El-Hanafy.

He went on to say that sharks reproduce according to their species; some we call “Ovoviviparous”, in which embryos develop inside eggs that are retained within the mother’s body until they are ready to hatch, while others lay their eggs directly into the water.

Also, there are shark species that live for decades and others that live for no more than five years.

Sharks are “tourism commodities”

Professor El-Hanafy believes that hunting sharks in Egypt is a huge economic loss, not an environmental one solely.

Sharks are tourism commodities that attract divers from all over the world and bring thousands of dollars into Egypt a year.

He added that “if a single shark lives for twenty years, its economic value in tourism may reach up to 4 million dollars, however, when it is hunted, its value decreases to around 150 to 300 dollars.”

El-Hanafy also warns against the dangers of eating shark meat, as it contains large amounts of mercury, which is a poisonous metal that causes incurable diseases if consumed in large quantities.

Looking at things from a different angle, overfishing also harms sharks indirectly, as it harvests large numbers of the fish they rely on for sustenance, leaving them to possibly starve.

Also, dumping kitchen waste in seas and oceans or throwing food to sharks has changed their behaviour and made them more hostile, leading to a rise in incidents where sharks attack humans.

Half of the shark species in Egypt have already disappeared

Mostafa Fouda, an adviser to the minister of environment for biodiversity, said that Egypt had about 50 species of sharks ranging in length from twenty centimeters to five meters, but in recent years, nearly half of them have disappeared due to several factors, such as overfishing, human interventions, pollution, and climate change.

He added that there are several laws and agreements prohibiting harming sharks, however, sharks are still hunted under the radar.

“In Egypt, according to the amended Environment Law of 2009, the possession of shark fins is punished by law. We need to continuously monitor the presence of sharks and prohibit the use of large nets in areas where they are likely to be found,” Fouda said.

Neils Klager, the spokesman for the ‘STOP Finning – STOP the Trade’ initiative, has noted that EU countries still have high percentages of shark finning despite the official ban issued in 2013.

European citizens decided to launch this initiative last year to call for an end to trading fins in the EU.

“Although finning is prohibited in the EU, shark fin trade is not. Sharks are still hunted down; there are markets to sell their meat, and fin business is conducted away from the public eye … let us leave fins naturally attached,” Klager said.

Other threats

According to David Campbell, the founder of the MarineBio Conservation Society for Marine Life, sharks managed to survive several mass extinction events, however, during the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event 66 million years ago, about 90 percent of all shark species in the open ocean became extinct; and now, in his opinion, sharks are facing yet again the risk of mass extinction.

“It is not just overfishing that threatens them directly, there are many additional threats that are not fully understood such as climate change and the map of the distribution of other predators that are affected by human fishing; British research found the presence of plastic fragments in the digestive tracts of 67 percent of sharks that were examined. We know that plastic may carry toxins and pathogens, but its potential impact on sharks at this point is unknown,” Campbell explained.

He added that important nursing areas for sharks such as mangroves and estuaries have also been endangered by human activities including fishing and climate change.

The need for joint efforts

Levis Kvaje, the coordinator for ecosystems and biodiversity at the United Nations Environment Programme in Africa, said that shark hunting causes an ecological imbalance that can lead to catastrophic results, as they grow slowly, mature late, and produce very few pups, so overfishing will lead to their extinction on the medium to long term.

He also added in special statements on the sidelines of a workshop organised by Africa21 on biodiversity that preserving sharks needs cooperation between countries in order for all this work to be effective, noting that the United Nations Environment Programme — through the Convention on Migratory Species — calls for international cooperation to address the excessive exploitation of sharks.