Published: September 20, 2023

India and Canada have engaged in tit-for-tat diplomatic expulsions as part of an escalating row over the killing of a Sikh separatist leader on Canadian soil.

The expulsions follow claims by Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau that there are “credible allegations” linking the Indian government of Narendra Modi with the death of Hardeep Singh Nijjar. Nijjar, a prominent member of the Khalistan movement seeking to create an independent Sikh homeland in the Indian state of Punjab, was shot dead on June 18, 2023, outside a Sikh cultural center in Surrey, British Columbia.

With tensions between the two countries rising, The Conversation reached out to Mark Juergensmeyer – an expert on religious violence and Sikh nationalism – at the University of California, Santa Barbara, to bring context to a diplomatic spat few saw coming.

1. What is the Khalistan movement?

“Khalistan” means “the land of the pure,” though in this context the term “khalsa” refers broadly to the religious community of Sikhs, and the term “Khalistan” implies that they should have their own nation. The likely location for this nation would be in Punjab state in northern India where 18 million Sikhs live. A further 8 million Sikhs live elsewhere in India and abroad, mainly in the U.K., the U.S. and Canada.

The idea for an independent land for Sikhs goes back to pre-partition India, when the concept of a separate land for Muslims in India was being considered.

Some Sikhs at that time thought that if Muslims could have “Pakistan” – the state that emerged through partition in 1947 – then there should also be a “Sikhistan,” or “Khalistan.” That idea was rejected by the Indian government, and instead the Sikhs became a part of the state of Punjab. At that time the boundaries of the Punjab were drawn in such a way that the Sikhs were not in the majority.

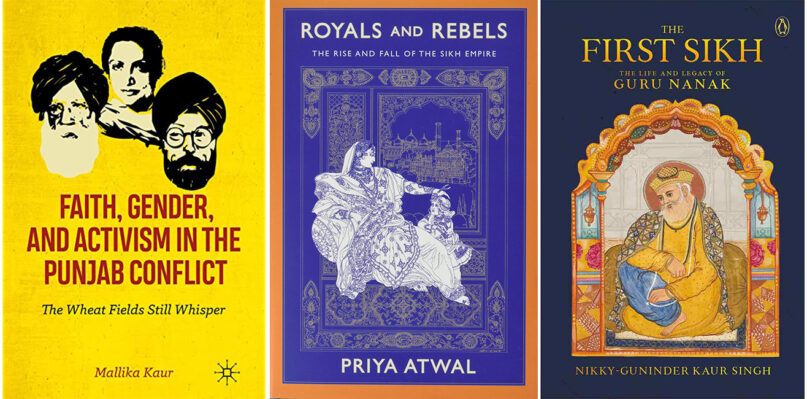

But Sikhs persisted, in part because one of the central tenets of the faith is “miri-piri” – the idea that religious and political leadership are merged. In their 500-year history, Sikhs have had their own kingdom, have fought against Moghul rule and constituted the backbone of the army under India’s colonial and independent rule.

In the 1960s, the idea of a separate homeland for Sikhs reemerged and formed part of the demand for redrawing the boundaries of Punjab state so that Sikhs would be in the majority. The protests were successful, and the Indian government created Punjabi Suba, a state whose boundaries included speakers of the Punjabi language used by most Sikhs. They now compose 58% of the population of the revised Punjab.

The notion of a “Khalistan” separate from India resurfaced in a dramatic way in the large-scale militant uprising that erupted in the Punjab in the 1980s. Many of those Sikhs who joined the militant movement did so because they wanted an independent Sikh nation, not just a Sikh-majority Indian state.

2. Why is the Indian government especially concerned about it now?

The Sikh uprising in the 1980s was a violent encounter between the Indian armed police and militant young Sikhs, many of whom still harbored a yearning for a separate state in Punjab

Thousands of lives were lost on both sides in violent encounters between the Sikh militants and security forces. The conflict came to a head in 1984 when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi launched Operation Blue Star to liberate the Sikh’s Golden Temple from militants in the pilgrimage center of Amritsar and capture or kill the figurehead of the Khalistan movement, Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale. He was killed in the attack, and Sikhs around the world were incensed that their sacred place was violated by police action. Indira Gandhi was assassinated in retaliation by Sikh members of her own bodyguard.

In recent years, several firebrand Sikh activists in India have reasserted the idea of Khalistan, and the Indian government fears a return of the violence and militancy of the 1980s. The government of Narendra Modi wants to nip the movement in the bud before it gets too large and extreme.

3. What is the connection between the Khalistan movement and Canada?

After the Sikh uprising was crushed in the early 1990s, many Sikh activists fled India and went to Canada, where they were welcomed by a large Sikh community – many of whom had been sympathetic to the Khalistan idea. A sizable expatriate community of Sikhs has been growing in the country since the early 20th century, especially in British Columbia and Ontario.

Sikhs have been attracted to Canada not only because of its economic opportunities but also because of the freedom to develop their own ideas of Sikh community. Though support for Khalistan is illegal in India, in Canada Sikh activists are able to speak freely and organize for the cause.

Though Khalistan would be in India, the Canadian movement in favor of it helps to cement the diaspora Sikh identity and give the Canadian activists a sense of connection to the Indian homeland.

4. Has the Canadian government been sympathetic to the Khalistan movement?

The diaspora community of Sikhs constitutes 2.1% of Canada’s population – a higher percentage of the total population than in India. They make up a significant voting block in the country and carry political clout. In fact, there are more Sikhs in Canada’s cabinet than in India’s.

Although Trudeau has assured the Indian government that any acts of violence will be punished, he also has reassured Canadians that he respects free speech and the rights of Sikhs to speak and organize freely as long as they do not violate Canadian laws.

5. What is the broader context of Canada-India relations?

The Bharata Janata Party, or BJP, of India’s Prime Minister Modi tends to support Hindu nationalism.

Recently, the Modi government used “Bharat” rather than “India” when referring to the country while hosting the G20 conference, attended by President Joe Biden, among other world dignitaries. “Bharat” is the preference of Hindu nationalists. This privileging, along with an increase in hate crimes, has led to an environment of fear and distrust among minorities, including Sikhs and Muslims, in India.

Considering the high percentage of Sikhs in Canada’s population, Trudeau understandably wants to assert the rights of Sikhs and show disapproval of the drift toward Hindu nationalism in India.

And this isn’t the only time that Trudeau and Modi have clashed over the issue. In 2018, Trudeau was condemned in India for his friendship with Jaspal Singh Atwal, a Khalistani supporter in Canada who was convicted of attempting to assassinate the chief minister of Punjab.

Yet both countries have reasons to try to move on from the current diplomatic contretemps. India and Canada have close trading ties and common strategic concerns with relationship to China. It is likely that, in time, both sides will find ways to cool down the tensions from this difficult incident.

Professor of Sociology and Global Studies, University of California, Santa Barbara

https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/2023/09/canada-expels-indian-diplomat-as-it.html

MODI SECRET POLICE ACTIVE IN CANADA

LA REVUE GAUCHE - Left Comment: Search results for AIR INDIA CSIS RCMP