Modern Hinduism is fascism and racism. It is the origin of what we would call modern Fascism. Based on a religious caste system that is Aryan in origin, it divides up the world into three castes, warriors, priests, merchants, and in a slave class; the Dalit's or Untouchables. India Caste System Discriminates

The influence of Hindu Fascism on the Occult is well documented. Especially in the racialist constructs of Madame Blavatsky and her Theosophical movement. It is the concept of the Secret Chiefs, of higher beings who contact select humans, usually Caucasian Europeans, while relegating other 'races' of humanity to lesser rungs in the celestial hierarchies. Hence the belief in reincarnation, karma, dharma, etc. gets interepreted as the need for these lesser races to evolve to be accepted into the divine prescence fo the Secret Chiefs.

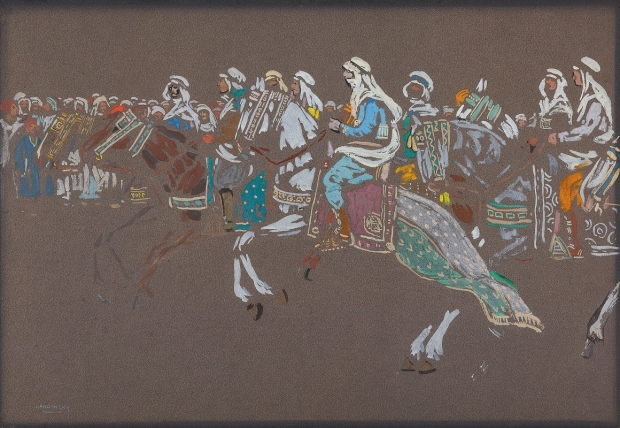

Later Aryan racialists would look at India as the home of the purist of the Aryan social constructs, that is the caste system, which they equated with the Indo-European peoples and as dating back to the orginal Aryan/Germanic expansion into the region. Savtri Devil, Hitlers Priestess was such a Indo-Aryan revivalist. The underlying construct of Hinduism is of whiteness/light verus black/darkness, which appealed to the Aryan racialists.

Dalit: The Black Untouchables of India

Originally published in India under the title Apartheid in India, V.T. Rajshekar's passionate work on the plight of the Indian Dalits was first introduced to North American readers through the publication of DALIT: The Black Untouchables of India in 1987. This book is the first to provide a Dalit view of the roots and continuing factors of the gross oppression of the world's largest minority (over 150 million people) through a 3,000 year history of conquest, slavery, apartheid and worse. Rajshekar offers a penetrating, often startling overview of the role of Brahminism and the Indian caste system in embedding the notion of "untouchability" in Hindu culture, tracing the origins of the caste system to an elaborate system of political control in the guise of religion, imposed by Aryan invaders from the north on a conquered aboriginal/Dravidian civilization of African descent. He exposes the almost unimaginable social indignities which continue to be imposed upon so-called untouchables to this very day, with the complicity of the political, criminal justice, media and education systems. Under Rajshekar's incisive critique, the much-vaunted image of Indian nonviolence shatters. Even India's world-celebrated apostle of pacificsm emerges in less saintly guise; in seeking to ensure Hindu numerical domination in India's new political democracy, Mahatma Gandhi advocated assimilating those whom Hindu scriptures defined as outcastes (untouchables) into the lowest Hindu caste, rather than accede to their demand for a separate electorate. Rajshekar further questions whether the Brahminist socio-political concepts so developed in turn influenced the formation of the modern Nazi doctrine of Aryan supremacy, placing the roots of Nazism deep in Indian history.

At the Culture and the State Conference at the U of A three years ago there was a concurrent conference of Dalit's from across North America. It was organized by my comrade John Ames. It was there I picked up their materials denonucing Hinduism as Racism and Fascism. These texts advocated a secular socialist humanist perspective on the Dalit struggle against the feudalist religion and politics of Hinduism.

Many Dalit groups, taking their cue from civil liberties organizations, ignore much of the economic ground for untouchability. Communist leader Brinda Karat notes that “only Communist inspired movements, enabled by the active participation of Dalits, have led to concrete gains against casteism.” In West Bengal, she shows, the Communist government initiated land reform that now forms “the backbone of Dalit self-respect and dignity in the State.”Badges of Color

Dalit Voice - The Voice of the Persecuted Nationalities Denied Human Rights

Dalit Voice was the first Indian journal to expose this closely guarded secret and shock the outside world and make history. That is how Dalit Voice has become the organ of the entire deprived destitutes of India, the original home of racism. Started in 1981 by V.T. Rajshekar, its Editor and founder, Dalit Voice, the English fortnightly, has become the country's most powerful "Voice of the Persecuted Nationalities Denied Human Rights". A veteran journalist, formerly of the Indian Express, powerful and fearless writer, V.T. Rajshekar, had to face the wrath of the ruling class, arrested many times, several jail sentences, passport impounded and subjected to total media boycott.

The Dalits are not only literal shit collectors in India they are also the largest group of workers in the service sector including government and the public sector. The political activism of the Dalits has been to unite in unions, broad based populist political parties, movements for womens rights, etc. to confront the Hindu Caste State in India.

Dalit Rising

Ghettoised Indians of the gutter society, eternally condemned. Not anymore, writes Amit Sengupta. The uprising is not a revolution, but it is no less

|

Buddha Smiles: Mass-conversion of dalits to Buddhism, November 4, 2001 Delhi |

The sun of self-respect has burst into flame Let it burn up these castes!

Smash, Break, Destroy These walls of hatred

Crush to smithereens this aeons-old school of blindness Rise, O People!

Marathi song, anti-caste movement, 1970s

In other words, five thousand years and more after, almost 60 years after ‘Independence’, dalits in India are a priori condemned, even before they are born. Even after they die when they are buried in separate village graveyards. Even when they become educated or employed, within or outside the politics of half-fake affirmative action.

Unlike in Punjab, with plus 30 percent dalit population, many of them economically well-off, not dependent on land, where Kanshiram begun his first mobilisation. The dalit-sufi secular traditions (they control dargahs) are as strong here, as is the old Ghadarite-Leftist-radical traditions — be it during the freedom struggle, or in the great sacrifices made against terrorism. The Mansa and Talhan movements are examples of organised dalit reassertion: political and ideological (see story).

In Bant Singh Inquilabi’s amputated limbs, lies the epic story of a nation defiled, like his raped daughter in Mansa. But the truth is that this ‘invisible nation’ is refusing to accept its fatedness anymore. As in Gohana in Haryana, in Bhojpur in Bihar, Ghatkopar in Mumbai, Talhan in Punjab, this rising is rising like a wave on a full moon night. It’s only that we only want to see the dark side of the moon.

|

The Politics of the Caste System and the Practice of Untouchability

The Hindu religious belief that" ALL HUMAN BEINGS ARE NOT BORN EQUAL" is deeply entrenched in the psyche of the upper-caste Hindus, leading them to see themselves as a superior race destined to rule and the out-castes (the Untouchables or Dalits) an inferior race born only to serve. This system, which has resulted in the destitution of millions of people due to racial discrimination, has not changed one iota after 50 years of Indian independence.

|

"For the ills which the Untouchables are suffering, if they are not as much advertised as those of the Jews, and are not less real. Nor arc the means and the methods of suppression used by the Hindus against the Untouchables less effective because they are less bloody than the ways which the Nazis have adopted against the Jews. The Anti-Semitism of the Nazis against the Jews is no way different in ideology and in effect from the Sanatanism of the Hindus against the Untouchables.The world owes a duty to the Untouchables as it does to all suppressed people to break their shackles and set them free." Dr. B.R. Ambedkar in a preface to his book,

"Gandhi and the Emancipation of Untouchables" - 1st September 1943

Man who redefined Dalit politics- The Times of IndiaOctober, 10, 2006NEW DELHI: Kanshi Ram, the Dalit icon who changed the political landscape of north India, was cremated as per Buddhist rituals at a funeral conducted by his political legatee, Mayawati, after Delhi High Court turned down the plea of his family for staying the last rites.

For a man who single-handedly turned the politics of North India on its head by thrusting Dalits as a factor in the regional power-play, Kanshi Ram's end was rather sedate, passing away on Monday, at 72, after being confined to bed for almost four years.

As in life, Kanshi Ram, in death, did not miss to shock his main haters — the urban middle classes — as he pulled the subaltern in droves on to the Capital's roads, throwing them off gear in sweltering heat.

Post-independence, Kanshi Ram redefined Dalit politics in the idiom of defiance. Hailing from a Ramdasiya Sikh family of Ropar and employed as a research assistant in a defence ministry lab, he resigned over the right of Dalit staff to get leave to celebrate Ambedkar and Valmiki jayantis.

What unfolded was a long-drawn mobilisation of Dalits, which changed political faultlines of the Hindi belt, marked by rebellious rhetoric and neat networking.

Kanshi Ram first targeted the better-off among Dalits, who had benefited from job quota. The result was the birth in 1978 of the Backwards and Minority Communities Employees Federation (BAMCEF), the first countrywide network of government employees from these categories.

APPRAISAL KANSHI RAM

KANSHI RAM The Dalit Chanakya

The Dalit Chanakya If Ambedkar was theory, Kanshi Ram was practice. Roaring practice.

If Ambedkar was theory, Kanshi Ram was practice. Roaring practice. RAMNARAYAN RAWAT

RAMNARAYAN RAWAT Magazine | Oct 23, 2006The dalit in India - caste and social class

Magazine | Oct 23, 2006The dalit in India - caste and social class THE dalit or "Untouchable" is a government servant, the teacher in a state school, a politician. He is generally never a member of the higher judiciary, an eminent lawyer, industrialist or journalist. His freedom operates in designated enclaves: in politics and in the administrative posts he acquires because of state policy. But in areas of contemporary social exchange and culture, his "Untouchability" becomes his only definition. The right to pray to a Hindu god has always been a high caste privilege. Intricacy of religious ritual is directly proportionate to social status. The dalit has been formally excluded from religion, from education, and is a pariah in the entire sanctified universe of the "dvija." (1)

Unlike racial minorities, the dalit is physically indistinguishable from upper castes, yet metaphorically and literally, the dalit has been a "shit bearer" for three millennia, toiling at the very bottom of the Hindu caste hierarchy. The word "pariah" itself comes from a dalit caste of southern India, the paRaiyar, "those of the drum" (paRai) or the "leather people" (Dumont, 1980: 54).

Barbaric Assault on Bant Singh (AIALA Leader)

Petition to Prime Minister of India

We the undersigned condemn the savage and barbaric assault by powerful Congress-backed Jat landlords which has left Bant Singh, Dalit leader of the Mazdoor Mukti Morcha (All-India Agrarian Labour Association) in Mansa, Punjab, with both hands and one leg amputated. Further we note that this criminal attack was planned in retaliation for Bant Singh’s sustained campaign against caste and gender based power and violence, and in particular, his struggle to bring his minor daughter’s rapists to justice. We stand by Bant Singh and his family in the face of this unspeakable tragedy and we believe passionately that such atrocities cannot be acceptable in 21st century India.

Dalit Religious Conversion

A Struggle for Humanist Liberation Theology

The development of Buddhist and Christian conversions as a political force for change is key to the Dalit philosophy. Rather than being absorbed into their new religion, the Dalit's use religious conversion to counter the hegemonic cultural domination of Hinduism. In that they adapt their new religious affiliations to meet their needs, ironically which are based on a humanistic and secular view of the world that oppresses them.

Despite advances, India's lowest Hindu castes remain downtrodden |

Tens of thousands of people are due to attend a mass conversion ceremony in India at which large numbers of low-caste Hindus will become Buddhists.

The ceremony in the central city of Nagpur is part of a protest against the injustices of India's caste system.

By becoming Buddhists low-caste Hindus, or Dalits, can escape the prejudice and discrimination they normally face.

The ceremony marks the 50th anniversary of the adoption of Buddhism by the scholar Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar.

He was the first prominent Dalit - or Untouchable as they were formerly called - to urge low-caste Indians to embrace Buddhism.

Similar mass conversions are taking place this month in many other parts of India.

Several states governed by the Hindu nationalist party, the BJP, have introduced laws to make such conversions more difficult.

Dalit Theology-

Dalit-liberative hermeneutics is scientific and praxis-oriented.

The Travancore Pulaya mass conversion movement to Anglicanism in the latter half of 19th century was an expression of social protest. For thousands these conversions were protests heralding exit from the inhumanity of the caste system. These oppressed also saw the doors opening for them as a way out of the misery with the success of the anti-slave campaign championed by the missionaries.

Guru Ghasidas according to delivers of the Satnami panth was born on 18th December 1756 and died at the age of eighty in 1836. He was born in village Girodhpuri in Raipur district in a dalit family. Ghasidas was born in a socio-political milieu of misrule, loot and plunder. The Marath the local had started behaving as Kings. Ghasidas underwent the exploitative experiences specific to dalit communities, which helped him the hierarchical and exploitative nature of social dynamics in a caste-ridden society. From an early age, he started rejecting social inequity and to understand the problems faced by his community and to find solutions, he traveled extensively in Chhattisgarh.

Ghasids was unlettered like his fellow dalits. He deeply resented the harsh treatment to his brotherhood', and continued searching for solutions but was unable to find the right answer. In search of the right path he decided to go to Jaganath Puri and on his way at Sarangarh attained true knowledge. It is said that he announced satnam and returned to Giordh.On his return, he stopped working as a farm worker and became engrossed in Tapasya. After spending six months in Sonakhan forests doing tapasya Ghasidas returned and formulated path-breading principles of a new egalitarian social order. The Satnam Panth is said to be based on these principles formulated by Ghasidas.

Dissident Sects & Anti-Caste Movements:

Both Vedic ritualism and gnosis [supremacy of Brahmans] were bound to be called in question by the common people. The popular discontent found expression in dissident sects like Jainism (540-468 B.C.) and Buddhism (563-483 B.C.). There is no doubt that Jainism and Buddhism were the first attacks or revolts in general against the caste system.

Lord Buddha initiated a radical critique of contemporary religion and society. He was forthright in repudiating the caste system and the notion of ritual purity associated with it. One of his famous sayings runs like this:

No Brahmin is such by birth,

No outcaste is such by birth.

An outcaste is such by his deeds,

A Brahmin is such by his deeds.”

From out of the struggle between Vedic religion and heterodox movements like Jainism and Buddhism was born what is today called Hinduism, which reached its golden age in the Gupta period (300-700 A.D.). Many factors were responsible for this new development. Brahminism succeeded in integrating within itself popular religions. Popular deities were absorbed into the Vedic pantheon through a process of identification or subordination. Even Buddha was given the status of a vishnuite incarnation.

Dalit poems and sayings on evil brahminic system

Tell a Slave is a Slave!

Surely and invariably he will rebel!

For most of times Slaves know not they are Slaves!

Always they only keep enjoying and relishing their Slavery!

They say that had been their lives generations after generations!

That too over the many many millenniums!

Slogging in the fields and mines for the landlords!

Taking just a pittance in return and still be proud and happy!

Listen to this! This is what the landlords, who had raped butchered killed otherwise murdered in cold-blood, and burnt SC&ST Dalits say –

We had all along for generations employed them paid them given them grains, fed them and looked after them! Now they had forgotten all that, to believe in the Govt, go for Education, seek Govt Employment, trust the Parties, run behind the Party Workers, follow the useless Leaders, pin their Hopes on the meaningless Govt Programmes, lean on the fake NGOs, and repose faith in all those stupid Activists! And, they have turned against us, we who have been feeding them for Generations! We can’t understand this! Hence we had to teach them a Lesson! Discipline them! Put them in their Places! They are like our Children! They are our Responsibility! And in fact it is our Duty to Discipline them, and bring them back to the right path – their old ways!

That is it. The Landlords want now to reclaim the SCs&STs, bring them back under their total and tight control, and keep them in their fold, as in the good old days! The old bondage and slavery!

Yes, it is true! Many SC&ST Dalits still toil as Slaves to crude cheap landlords and goons! They don’t realise their status and slavery. They don’t know that the World had changed!

One need not be surprised or feel shocked by this ignorance, and lack of knowledge or realisation of the World. After all they are poor rural labourers of backward feudal areas! But even the educated and employed SC&ST Dalits are not aware of all their Dues and Rights! In fact the depth of their ignorance is shocking! If the Dalits’ Knowledge of Dalit Issues are so shallow, what can we say of others understandings of Dalit Problems! It is for this reason that any writings on Dalit Issues, and Dalit Views have to be in so much of, perhaps what appears to be too detailed! That includes Dalit Poetry on Dalit Issues and Problems! Hence, the Prose like Poetry, or Prose rendering of Poetry! That may not matter, but that also so inevitable!

Dalit Womens Struggles

The oppression of women is a double burden in slave societies, and amongst the Dalit's women have played an important role in linking their struggles with that of being Dalits and women. It has created a syncratic feminism that is reflected in the movement regardless of their religious affiliations. Again emphasising the humanist nature of Dalit relgious conversion.

Ruth Manorama, voice of Dalits

Ruth Manorama is a women's rights activist well known for her contribution in mainstreaming Dalit issues. Herself from the Dalit community, she has helped throw the spotlight on the precarious situation of Dalit women in India. She calls them "Dalits among the Dalits." A peacewomen profile from the Women's Feature Service and Sangat.

DALIT WOMEN: The Triple Oppression of Dalit Women in NepalTerai Dalit Women - Violation of Political RightsAttacks on Dalit Women: A Pattern of Impunity - Broken People ...FEMINIST DALIT ORGANIZATIONDalit Women Literature ReviewDalit Feminism By M. Swathy Margaret

EMPOWER DALIT WOMEN OF NEPAL is a small human rights organization for Dalit women, the “untouchable” women on the lower rungs of Nepal’s caste hierarchy.

| |

|

|

|

| Martin Macwan’s Dalit Shakti Kendra in Gujarat provides vocational training to dalit youth. More importantly, it gives them a sense of identity |

|

|

|

It began as a small agitation in Ranpur, Dhanduka taluka, Gujarat. Women of a particular dalit sub-caste, who still performed the menial task of manual scavenging despite legislation against it, had asked the panchayat for new brooms but were refused on grounds that there was no budget for it.  This was a seminal moment for Martin Macwan, a dalit activist who had set up the Navsarjan Trust in 1989 against scavenging. “What totally devastated me was that they were not agitating against the practice. They were merely begging the panchayat to give them more brooms to prevent their hands from being soiled with shit. They didn’t dream of eliminating scavenging.” (Mari Marcel Thekaekara in Endless Filth, Saga of the Bhangees) This was a seminal moment for Martin Macwan, a dalit activist who had set up the Navsarjan Trust in 1989 against scavenging. “What totally devastated me was that they were not agitating against the practice. They were merely begging the panchayat to give them more brooms to prevent their hands from being soiled with shit. They didn’t dream of eliminating scavenging.” (Mari Marcel Thekaekara in Endless Filth, Saga of the Bhangees)

|

Globalization and the Dalit

The Green Revolution in India as well as the later developments around GMO's etc. have had a disproportionate negative impact on the Dalit's agricultural communities. Modernization and industrialization have not benefited these peasant economies, as much as chaining the Dalits to their landlords.

Dalits and Adivasis have never been the part of the conventional trade systems. Today they are faced with the horrible hostility of trade and market policies. In recent times trade entered the scene on mass scale through the principles of globalisation, liberalisation and privatisation. Mega industrial production still plays the key role in all trade deal not only at the national level but also at the international level.

Industrialisation, which made a colourful and dreamy entry, is turning out to be the worst form of human development. The steady economic growth of industries with active support from the state machinery is directly proportional to the unchecked exploitation of masses. Most of them belong to marginalized communities such as Dalits, Adivasis, women, working class, etc. Though during the independence struggle “land to the tillers” and “factory to the workers” prominently came on to the national agenda, nowhere in India had we witnessed the later one being implemented in the post independence era. Resultant displacement, migration, repercussion of workers, loss of land and livelihood, pilfering state revenue, forest resources, etc. has outgrown to monstrous level.

This has amplified particularly with WTO taking the centre stage of all sorts of trade related agreements and transactions at the international level. Trade is no longer buying and selling of goods and services but it encompasses issues like Intellectual Property Rights. With this the global market has wide open for exploration and exploitation of resources under the aegis of free trade. Industrialised nations found their tools to maintain supremacy on world trade. Prophets of trade and commerce argue that free trade maximises world economic output. This is what is considered to be progress. But what we have been witnessing with the Dalits and Adivasis in India is diametrically opposite to these claims.

Dalit woman shows the way to better yieldsDalit Academic Perspectives

A Dalit Bibliography558, February 2006, Dalit PerspectivesSeminars and Workshops of Deshkal Society | Seminars on Dalit Dalit ResourcesNepal Dalit InfoCounterCurrents.org Dalit Issues Home PageDalit Freedom Network: Abolish Caste, Now and ForeverDalit foundation - Accelerating change for equalityDalit Welfare Organisation (DWO)Dalit Human RightsPunjab Dalit Solidarity-A blogNational Campaign on Dalit Human Rights (NCDHR)The Bhopal Dalit DeclarationInternational Dalit Solidarity Network Formed in March 2000, the International Dalit Solidarity Network (IDSN) is a network of national solidarity networks, groups from affected countries and international organisations concerned about caste discrimination and similar forms of discrimination based on work and descent.

IDSN campaigns against caste-based discrimination, as experienced by the dalits of South Asia to the Buraku people of Japan, the sab (low caste) groups of Somalia, the occupational caste people in West Africa and others.

The work of IDSN involves encouraging the United Nations, the European Union and other bodies to recognise that over 260 million people continue to be treated as outcasts and less than human and that caste-based discrimination must be regarded as a central human rights concern. IDSN insists on international recognition that "Dalit Rights are Human Rights" inasmuch as all human beings are born with the same inalienable rights.

IDSN brings together organisations, institutions and individuals concerned with caste-based discrimination and aims to link grassroots priorities with international mechanisms and institutions to make an effective contribution to the liberation of those affected by caste discrimination.

More than 260 million people worldwide continue to suffer under what is often a hidden apartheid of segregation, exclusion, modern day slavery and other extreme forms of discrimination, exploitation and violence.

See:

India

Find blog posts, photos, events and more off-site about:

dalit, untouchables, India, Hindu, Hinuism, Fascism, Aryan, Blavatsky, Occult, racism, politics, slaves, human-rights, women, feminism, Nepal,