Dr. Susan Rosenthal describes the rise of Canada’s public health system during labor’s rebellious postwar period and the corporate profiteering by which it is now being destroyed.

Ontario’s Bill 60 has delivered a potential death blow to public Medicare. If it becomes law, the provincial medical system will no longer operate as a public service but as a profit-taking business managed by the private sector.

While defenders of public Medicare blame Conservative Premier Doug Ford, British Columbia, Quebec and Saskatchewan are going down the same road.

If we hope to reverse this disaster, we need to know how Canadians won Medicare in the first place, and why they are losing it.

World War II saw a global upsurge of labor protest. Union membership more than doubled in Canada, and the number of strikes tripled. During the early 1940s, one-third of all workers in Canada were on strike. To calm the rise in worker rebellion, governments agreed to fund social programs like Medicare.

At the time, Canada had virtually no public medical system. Doctors charged whatever they pleased and bankruptcy from high medical bills was common.

The Canadian Labour Congress pushed for a comprehensive public medical system available to all. The corporate class pushed back, opposing any government control over medicine. Insurance companies feared losing business. Drug companies feared losing profits. And doctors were horrified at the thought of losing their elite status as independent entrepreneurs.

On July 1, 1962, Saskatchewan launched North America’s first government insurance plan to cover hospital care and doctor visits. That same day, 90 percent of Saskatchewan’s doctors went on strike. The doctors’ strike was deeply unpopular and collapsed after 23 days.

The 1964 federal Royal Commission on Health Services suggested a class compromise. For the working class, it recommended government-funded medical insurance. For the business class, it recommended the right to deliver medical services “free of government control or domination.”

Class Compromise

The Saskatchewan Legislative Building. (Stonedan, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

The business class and the working class have opposite interests. For the working-class, medical care is a human right and a vital necessity. For the business class, healthy profits take priority. This class conflict shapes the quality and accessibility of public programs.

Workers in Canada were strong enough to win public funding for medical care, but not strong enough to kick out the profiteers and win the fully public system they wanted.

The federal Medical Care Act of 1966 was based on class compromise. It established government funding for hospital care and doctors’ visits, while excluding essential medical services such as dentistry, eye care, home care, long-term care and prescriptions. These exclusions enabled insurance companies to continue selling policies to cover such services. (The insurance industry is exempt from human-rights legislation and can legally deny coverage on the basis of a person’s age, past medical history and current state of health.)

Another class compromise was to maintain private-sector control over out-patient care. Doctors were allowed to remain independent contractors charging for each service they provide.

From the start, Canadian Medicare was designed as a two-tier system that gave the private sector room to grow. And grow it did.

Funding Cuts

When Medicare began, Ottawa agreed to pay half the cost of all medical services performed in hospital. This did not last.

In response to the 1970s’ global recession, governments boosted profits by cutting corporate taxes.

Canadian corporations contributed more than half of all tax revenue in the 1950s. Today, they contribute around 12 percent. To offset the loss of corporate revenue, governments cut spending on public programs.

“From the start, Canadian Medicare was designed as a two-tier system that gave the private sector room to grow. And grow it did.”

In 1977, the Trudeau Liberals reduced the federal share of medical funding from 50 percent to 20 percent, forcing the provinces to also reduce their spending. The federal share has varied since then, and currently stands at 22 percent. Less funding for public Medicare enabled private corporations to step in to fill the need.

The 1984 Canada Health Act reassured nervous Canadians that Medicare was safe. Behind the scenes, politicians continued to advance the privatization agenda.

The Drive to Privatize

Business and government view public-sector spending as a drain on the economy. While public facilities can deliver social services more effectively, this costs money. The same services delivered for profit in the private sector make money, and that is seen as a benefit for the economy.

In Caring for Profit (1998), Colleen Fuller documents how plans to open Medicare to the private sector date back to the 1990s’ push to integrate the world economy (“globalization”).

Corporations need a profitable home base on which to grow into global players. Governments provide that base by, among other measures, opening public services to the private sector.

A 1994 Report to the Ontario Ministry of Health advised expanding the domestic for-profit medical industry to help it compete in the global market. The federal government was on the same track. As a 1997 Report for Industry Canada stated, promoting Canadian companies as global health-keepers is the main objective driving the strategies and plans of the government for the medical devices, pharmaceutical and health-services sector.

The Canada Health Act compels government to pay for all medical services provided in hospital. It does not prevent those services from being removed from hospital and handed to the private sector.

Every medical service that can be removed from hospital has been removed or soon will be. The only services left in the public sector will be those too unprofitable to privatize.

Loblaw Companies Ltd. is Canada’s largest food and drug retailer, with more than 2,400 retail outlets across Canada, including its Shoppers Drug Mart subsidiary. Ninety percent of Canadians live within 10 km of one of those outlets, enabling Loblaw to position itself as a major private provider of medical services.

In 2006, Loblaw purchased MediSystem Pharmacy. In 2020, it launched the PC Health app that offers live chats with registered nurses and dietitians. In 2021, it purchased a top chain of physiotherapy clinics. New grocery and pharmacy locations will include clinic spaces and older locations are being retrofitted to offer medical services.

Hospitals themselves are being privatized through Public Private Partnerships (P3s). A P3 hospital is built with public funds and managed by a private corporation. There are more than 50 P3 hospitals across Canada, and the Canadian Council for Public-Private Partnership is pushing for more P3s in medicine, education, transportation and public utilities.

P3s are a prime investment for the private sector. Governments put up the money and take all the risk, while corporations take all the profit. It’s a familiar story: we pay and they profit.

Working Conditions

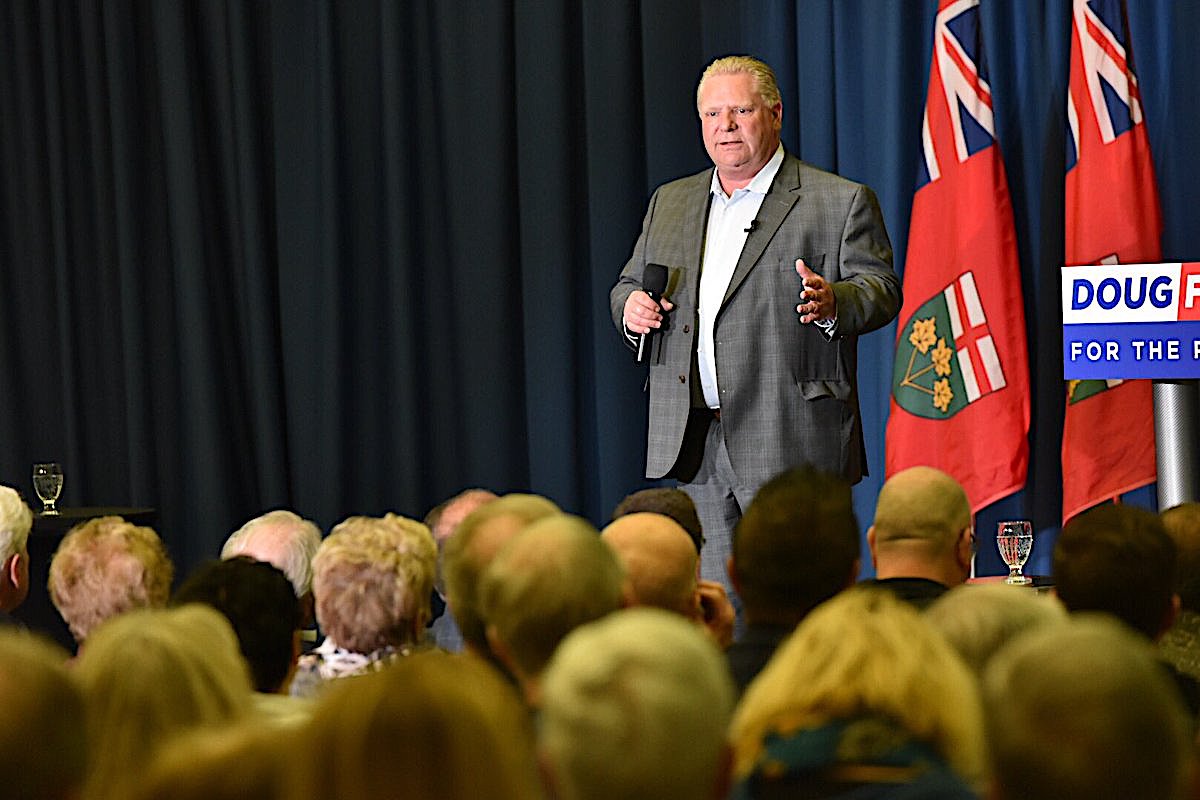

Doug Ford campaigning in Sudbury during the 2018 Ontario general election. (CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons)

Whenever the private sector take over a public program, we see a consistent pattern of higher cost, lower quality service and deteriorating working conditions. A 2021 report comparing public and private sector workers in Ontario found,Workers in the government sector (federal, provincial, and local) earn 11 percent higher wages on average than their private-sector counterparts.

84 percent of government workers are covered by a registered pension plan, compared to just 25 percent of private-sector workers.

Government workers retire about 2.5 years earlier.

Private sector workers are more than four times more likely to lose their jobs.

Schedule 2 of Bill 60 allows government to reduce spending in the public sector by creating new categories of lesser-skilled, lower-waged medical workers to perform duties currently performed by registered doctors, nurses and medical technicians.

Poor quality working conditions result in poor quality service.

“Governments put up the money and take all the risk, while corporations take all the profit. It’s a familiar story: we pay and they profit.”

For-profit facilities invest the minimum in patient care so they can maximize dividends to shareholders. That is why the Covid death rate in Ontario’s for-profit nursing homes was four times higher than it was in public municipal nursing homes. Yet these same for-profit corporations, who are responsible for the deaths of 4,000 Ontario residents, were granted 30-year licenses and permission to add 18,000 more long-term-care beds.

Burden the Family

Social services distribute the cost of caring across society. Loss of public support for medical care, childcare, home care, disability support and long-term care shifts the burden of care onto unpaid family care-givers, who are mostly women.

Employers generally pay women less because of their family and care-giving responsibilities. When public care is not available, the person with the lowest wage typically stays home to provide it. The result is a vicious circle that traps women in lower-waged jobs and also in the unpaid work of domestic care-giving.

Globally, it would cost $11 trillion annually to provide the socially necessary care that women provide for free in the home. That’s more than triple the size of the world tech industry. The system saves a ton of money, while 42 percent of all women cannot get waged work because of care-giving responsibilities.

British Columbia Family Day 2016.

The increasing loss of public programs is increasing the need for home-care and for women to be home to provide it. Restricting or eliminating access to abortion is one way to do this.

Women rely on abortion care so they can stay in waged work, support their families and leave violent partners. Loss of access to abortion is driving vulnerable women out of waged work and trapping them in the family.

Growing economic reliance on the family is also driving horrific attacks against trans people, gender rebels, drag artists, cross-dressers — any behavior that challenges traditional family and gender roles.

Damage Control, Not Health Care

It used to be that women could get secure, well-paid, union jobs in the medical industry. No longer. In the 1990s, Ontario adopted a cost-saving, “just-in-time” staffing system pioneered by the auto industry.

In Saskatchewan, hospital managers followed nurses around with stopwatches to track and time every movement, from turning around (one second) to checking supply rooms (three seconds).

“The loss of public programs is increasing the need for home-care and for women to be home to provide it. Restricting or eliminating access to abortion is one way to do this.”

Just-in-time staffing relies more on casual workers than on permanent full-time staff. The result is rising costs, more overtime, more stress-related leave and thousands of nurses leaving hospital work.

Just-in-time staffing crippled the ability of hospitals to respond to the 2003 SARS outbreak and the Covid pandemic. Nevertheless, it is still in use, while governments demand even more cost-cutting measures.

Treating staff as replaceable widgets is stirring systemic violence. So is making people wait too long for the care they need, when they get it at all. No wonder patients lash out in desperation.

Hospitals have become dangerous workplaces where staff suffer beatings, sexual assault and racist attacks every day. In British Columbia, incidents of physical violence directed against medical staff more than tripled between 2015 and 2022.

Medical workers are seven times more likely than manufacturing workers and 45 times more likely than construction workers to be injured from violence on the job. Instead of making work safe, managers post signs warning, “abuse towards staff will not be tolerated.”

When cost-cutting results in fatal medical errors, hospitals are never held responsible for creating conditions that raise the risk of such errors. Instead, individual medical workers are blamed and criminally prosecuted.

A system that violates the health of its workers and those they serve should not be called a “health-care” system. It is a system of damage-control. Employers are free to sicken, injure, and kill workers, and the medical system manages the resulting damage.

Backlog

In The Shock Doctrine, the Rise of Disaster Capitalism (2007), Naomi Klein explained how the business class exploit social crises for profit.

While populations are reeling and disoriented, their economies are pillaged in a capitalist feeding frenzy. Public wealth is handed to the private sector and private debt is transferred to the public sector. A few become fabulously wealthy, and the majority are impoverished. By the time the population recovers, the economy has been looted and the theft sanctioned by law.

When the Covid pandemic overwhelmed public hospitals, governments promised to “build back better.” They did not mean better for the majority; they meant better for the profiteers.

The Ontario government insists that the pandemic-related backlog of more than 200,000 surgeries can be cleared only by doing them in private medical clinics. To promote this transition, the province under-spent its budget on public Medicare and overspent its budget on private clinics.

The public medical system could easily clear the surgical backlog if it had enough staff. In 2022, 158 emergency rooms in Ontario had to close for lack of staff, and hospital operating rooms remain underused for the same reason.

On a per-capita basis, Ontario has the lowest hospital funding, the fewest hospital beds, and the fewest nurses in the country. Fifteen thousand registered nurses and registered practical nurses have left Ontario because of low wages and abysmal working conditions, including the outrageous demand to work while sick during the pandemic.

The province insists that moving hospital surgeries to private clinics will reduce patient wait times. It will do the opposite.

No one can work in two places at the same time. Pulling medical staff away from public hospitals to work in private clinics will decimate the public system. Any reduction in wait times in the private sector will be offset by even longer wait times in the public sector.

To maximize profits, private clinics will do simple surgeries such as cataracts and hip-and-knee replacements, leaving more difficult, complex surgeries in the public system. When clinic surgeries become complicated, patients will be off-loaded to the public system, along with the cost of treating their complications (assuming patients survive the transfer).

The loss of simple surgeries will devastate small and rural hospitals. Complex surgeries were moved to larger centers some time ago. Without income from simple surgeries, smaller hospitals will have to close, reducing access in already under-served areas.

Private surgical clinics will not produce more family doctors. Last year, more than 2 million Ontarians did not have a family physician, 24 percent more than two years ago. The shortage of family doctors across Canada is predicted to more than double over the next seven years. Overwhelmed with patients, some Ontario doctors are offering rapid access to a nurse practitioner, for $30 a month.

The province says patients will not have to pay out-of-pocket in private facilities, but they will.

The Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) pays only a base rate. To meet shareholder demands for maximum profit, the province allows private clinics to “upsell” by charging patients a fee for premium or upgraded services. While politicians call this “patient choice,” those who cannot pay will have no choice. Those who can pay will be milked.

The push for maximum profit inevitably leads to fraudulent billing. As the Office of the Auditor General warned, the ministry has no oversight mechanism to prevent patients from being misinformed and being charged inappropriately for publicly funded surgeries.

Finally, the Canada Health Act does not compel government to pay for out-of-hospital care, so public funding will be reduced to the absolute minimum, returning us to pre-Medicare conditions.

Which Way Forward?

Downtown Ottawa, 2012. (Tullia, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

How can we stop the profiteers, revitalize public programs and improve working conditions in the public sector?

The Ontario Health Coalition (OHC) is a prominent research and advocacy organization that opposes profit-taking in medicine, lobbies for public Medicare and is mobilizing public opposition to Bill 60.

In 2016, the OHC launched a referendum campaign at 1,000 polling stations in 40 communities across the province. Almost 94,000 people voted, with 99.6 percent demanding that government stop cutting hospital funding and services.

The OHC is launching another referendum campaign to send the government an even stronger message to reject privatization and invest in the public system. Why would this referendum be more effective than the previous one?

Politicians already know that the majority want fully funded public services. A 2022 poll revealed that 92 percent of Canadians oppose funding cuts to healthcare, education, and other social programs, and 88 percent favour a wealth tax to fund these programs.

Public mobilization campaigns are based on the assumption that politicians will respond if enough people pressure them to do so. When such campaigns fail, blame is directed at a presumably uncaring or apathetic public, as recently expressed by one OHC representative.

There may not be a great impact as a result of the referendum, but it will inform Canadians who think they’ve got public health care. That Canadians are just unaware, completely zombie-like in their perspective is a grave misunderstanding. After decades of setbacks and defeats, most people feel powerless to improve things at work or in society. Their lives are getting harder, and they see no way forward.

Politicians lie (the Ontario premier campaigned on a promise not to privatize Medicare). Unions have failed to deliver real on-the-job improvements. And past public campaigns have proved ineffective. Discouraged people need a real win, not more campaigns that raise their hopes and deliver defeat.

No Democracy

Democracy literally means rule of the people. If Canadians lived in a democracy, they would have a fully public medical system, because the majority want it. The fact that they do not have such a system proves they do not live in a democracy.

There is no democracy in the economy. The majority get no say over what is produced, how it is produced, and for whom. The result is toxic pollution, deforestation, species extinction and global warming.

There is no democracy in foreign policy. Canadians did not vote to send troops to Haiti to put down a popular rebellion (again). They did not vote for Canada to sell weapons to Saudi Arabia or build military bases around the world. And they certainly did not vote for World War III.

There is no democracy at work. Workers have no say over what they do or how they do it, even though they know best what needs to be done and how to do it well and safely.

There is no democracy when it comes to spending the social surplus. Canadians do not get to vote on whether to invest in war or in the environment, in police or social supports, or in private or public services.

In a democracy, the business class would be forced to share their profits, which have never been higher.

In 2022, the Shell oil company posted a record profit of $40 billion, more than double what it raked in the previous year. Chevron reported a similar record-breaking profit. You could make $53,000 every single day for over 2,000 years and still not have that much. Nevertheless, every year, Canada gives $4.8 billion in subsidies to the fossil-fuel industry.

Shell station in Canada. (Raysonho, CC0, Wikimedia Commons)

Capitalism is the enemy of democracy. Any form of collectivism (prioritizing public need) is considered a threat to private enterprise, because it is. Premier Doug Ford calls government-funded or socialized Medicare “communism” and privatized medicine “freedom” — freedom for the few to profit at the expense of the many,

Capitalist Dictatorship

Modern technology could enable everyone to vote on every issue that affects their lives and society. However, capitalism is based on depriving the majority of what they need, and who would vote for that? To maintain capitalist rule, people are not allowed to vote on anything that might disrupt the flow of profit.

The entire social system is structured to transfer wealth from the working class to the business class. Every human activity is treated as an opportunity for profit-taking.

“We live in an anti-democratic, authoritarian, capitalist dictatorship. The entire social system is structured to transfer wealth from the working class to the business class.”

The dismantling of Medicare can only be understood in this context. Capitalism is based on the conversion of common property into private property. From the 18th century enclosure of common lands, to the current privatization of public services, capitalists strive to transform what belongs to all into what belongs exclusively to them. Their wealth is built on deprivation and their power on subjugation. Their greatest fear is a working-class rebellion that could end their rule.

Class Power

The quality of public programs does not depend on what the majority want or who they vote for but on the balance of class forces, that is, on which class is using its power to make the other back down.

Decision-makers respond to majority demands only when their power is threatened. When workers exercise power on the job, when they make the bosses back down, politicians get scared and deliver pro-worker reforms in hopes of buying labor ‘peace.’

Canada’s first Royal Commission to study government-funded health insurance was launched in 1919, the year of the Winnipeg General Strike.

Britain’s National Health Service (NHS) was established in 1948 to calm a post-war workers’ rebellion. As a Conservative member of the British Parliament warned, “If you don’t give the people reform, they will give you revolution.”

Canada’s Medicare system was consolidated in the context of rising workers’ struggles that peaked in the Quebec General Strike of 1972.

Picket line during the 1972 Québec general strike.

Since the mid 1970s, the working class have suffered decades of setbacks and defeats, losing much of what they won in the past, including solid union jobs, the 40-hour week, and robust public services.

The more workers retreat, the more the business class push their agenda, regardless of which political party is in office. The process of dismantling Medicare began in the 1970s and has continued under every form of government: Liberal, Conservative, and NDP (social democratic).

Experience shows that the problems created by capitalism cannot be solved by electing different politicians or parties to office. No matter who is in charge, a social system that is structured to exploit humanity and nature for profit cannot be made to do the opposite — promote the well-being of people and the planet.

Social systems are structured to achieve specific goals. The goal of capitalism is capital accumulation, which it does extremely well. The call to prioritize human need is a call to change the goal of society. This is no easy task. A different social goal requires a fundamentally different social system, one that only the international working-class can construct.

All Strikes are Political

All strikes are political battles over what matters more, human need or corporate greed.

Strikes are not merely means by which workers achieve gains in the workplace. Rather, they are moments in the process by which workers constitute themselves as a class — building solidarity, raising class consciousness, creating their own norms and institutions and discovering their own forms of class power. (Class Struggle Unionism, p.59)

When factory workers reject forced overtime, when education workers demand smaller classes, when nurses demand staff-to-patient ratios and when anyone demands higher wages, they are challenging the primacy of profit, the foundation of capitalism.

The outcome of these battles depends on which class uses their power to make the other back down.

The power of the capitalist class lies in their control over social institutions including the legal system, the courts, the police, and the media. However, the power of the working class is greater.

Workers are the vast majority, and nothing moves without their effort. Stopping work stops the flow of profit. When workers stand together, they can defeat the bosses and make governments change course. To keep workers down, the ruling class must block effective strikes.

Governments justify anti-strike legislation by insisting that strikes are not in the public interest. The opposite is true. Business-as-usual is not in the public interest. Successful strikes raise living standards, which is very much in the public interest.

Playing by the enemy’s rules is a sure way to lose a battle. To strike effectively, workers must be willing to violate restrictive labor laws and make them unenforceable.

After launching a solid, 17-day, illegal strike, Canadian postal workers won the legal right to strike in 1965.

That same year, Ontario hospital workers were denied the legal right to strike in order to hold down the wages of a predominately female, immigrant and under-paid workforce. (This same strategy is still used against public-sector workers.)

“Playing by the enemy’s rules is a sure way to lose a battle. To strike effectively, workers must be willing to violate restrictive labor laws and make them unenforceable.”

In 1981, 13,000 hospital workers across Ontario launched an illegal strike to protest wage cuts and degraded working conditions. They held out for nine days against hospital management, the provincial government, the courts, the police, and the media.

Initially, union officials for the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) opposed the strike. When workers struck anyway, union officials issued a statement of support, but failed to mobilize other CUPE locals to build the strike. Isolated, the strike crumbled in defeat.

Weak Unions

University of Toronto, 2015. (OFL Communications Department/Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

Why do union officials collapse strikes, as CUPE did recently with the education workers, instead of broadening them? Why did the Ontario Federation of Labour (OFL) surrender to wage-busting Bill 124 instead of mounting a mass public-sector strike to force the province to back down?

While union officials vigorously object to the loss of public services, they refuse to organize the class power of workers to make governments reverse course.

Union officials are committed to bargaining with the business class, not challenging their rule. To protect their relationship with the employer, union officials hold workers back, mounting ineffective strikes that typically end in defeat.

Unwilling to do what it takes to deliver real on-the-job improvements, union officials launch toothless public-mobilization campaigns. Instead of leading class rebellions, they pin their hopes on electing a labor-friendly government that will pass pro-labor laws, meaning, make capitalism work in their favor.

These are safe strategies for union officials. Lobbying campaigns make it appear that they are fighting for workers’ rights, without challenging the social order that violates those rights.

For workers, this has been a losing strategy. The social order must be challenged in order to win meaningful reforms.

Centering Work

Pandemic Physician: one of the doctors in Toronto who joined a protest at the conditions of homeless shelters during the Covid pandemic, April 15, 2022. (michael_swan/Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0)

Public-pressure campaigns appeal to all social classes to exert moral pressure on authorities to do the right thing. Such mobilizations can be powerful when linked with workplace battles. In the absence of workplace action, they can only threaten to vote for different politicians or parties. An electoral focus limits what can be achieved to what capitalism allows.

Public Medicare could be rebuilt if hospital workers won good contracts that a) pull money back into the public system and b) improve working conditions to attract and keep qualified staff. They cannot do this on their own, nor should they have to.

The labor movement is based on the principle that an injury to one is an injury to all. When any group of workers is attacked, all are at risk. When any group of workers win, it is easier for the next group to win. Workers have tremendous power when they stand together. Fighting separately is a recipe for defeat.

“Workers have tremendous power when they stand together. Fighting separately is a recipe for defeat.”

To build a fighting labor movement that can win real improvements, workers must be willing to challenge the existing order, including defying anti-worker laws. They must be willing to fight together, as a class. That means all-out support for every strike.

All-out support means public-sector workers striking together: medical, education, library, clerical, postal workers, all together. They all have the same employer – the government!

All-out support means public and private sector workers supporting each others’ strikes, not merely in words, but by swelling picket lines and mounting solidarity strikes. A strike that gains momentum day-after-day is the bosses’ worst nightmare. They will concede whatever they must to prevent a workers’ rebellion from growing beyond their control.

Who Can We Count On?

Covid exposed capitalist priorities for all to see. We saw corporations profit from the pandemic while doing nothing to protect their workers. We saw politicians accept millions of Covid deaths instead of legislating paid sick leave and making schools safe. In contrast, we saw ordinary working people risk their lives and those of their loved ones to serve the public.

Who can we count on to protect our public services? Corporations are not required to protect the public interest. Their only legal obligation is to deliver profits to shareholders.

Politicians will not protect the public when doing so means angering the business class and losing corporate donations.

The only people we can really count on are those who work in public services, because their job conditions directly affect the quality of our services.

Who would you rather manage a hospital? Executives and bureaucrats obsessed with the bottom line? Or medical and support staff who actually do the work? I will take my chance with workers in charge, any day.

It is useless to blame the loss of public Medicare on any particular politician or political party. All over the world, people are facing the same problem — a global capitalist system that values profit over human lives. The profiteers are taking everything away from us, and they will not stop until there is literally nothing left.

Last month, a million people marched in Madrid to protest the dismantling of their public medical system. Tens of thousands of nurses in the U.K. went on strike because they know that quality care cannot be delivered without quality working conditions. And in 2021, half of all strikes in the United States were strikes of medical staff.

Power on the job means power in society. A strong labor movement can win strong public programs. The loss of public programs signals a weak labor movement.

Class struggle won public services like Medicare, and class struggle is the only way to win them back. To succeed, workers must not allow the class enemy to dictate what is and is not acceptable. They must exercise their right to fight effectively, and not back down until they win.