Fast-running theropods tracks from the Early Cretaceous of La Rioja, Spain

- Article

- Open Access

- Published:

Scientific Reports 11, Article number: 23095 (2021)

Abstract

Theropod behaviour and biodynamics are intriguing questions that paleontology has been trying to resolve for a long time. The lack of extant groups with similar bipedalism has made it hard to answer some of the questions on the matter, yet theoretical biomechanical models have shed some light on the question of how fast theropods could run and what kind of movement they showed. The study of dinosaur tracks can help answer some of these questions due to the very nature of tracks as a product of the interaction of these animals with the environment. Two trackways belonging to fast-running theropods from the Lower Cretaceous Enciso Group of Igea (La Rioja) are presented here and compared with other fast-running theropod trackways published to date. The Lower Cretaceous Iberian fossil record and some features present in these footprints and trackways suggest a basal tetanuran, probably a carcharodontosaurid or spinosaurid, as a plausible trackmaker. Speed analysis shows that these trackways, with speed ranges of 6.5–10.3 and 8.8–12.4 ms−1, testify to some of the top speeds ever calculated for theropod tracks, shedding light on the question of dinosaur biodynamics and how these animals moved.

Introduction

One of the perennial questions in the paleobiology of non-avian theropod dinosaurs is their capacity for locomotion, e.g.1,2. How did they move? How fast did they go? Over the years, these questions have been approached from various points of view based on osteological information, with anatomical (e.g., morphology, muscular attachments, size) and anatomically-derived biomechanical models (e.g., mass, force, and momentum) being used to estimate the maximum speed of locomotion3,4,5,6,7. Another way of better understanding how extinct theropods moved is to examine their tracks and trackways, e.g.8. To this end, Alexander9 proposed an equation using dynamic similarity to calculate the absolute speed of dinosaurs from ichnological data on the basis of footprint length (to obtain the height at the hip) and stride length. This and other methods e.g.10,11 have been used in the last few decades by many ichnologists to analyse the locomotion dynamics shown by hundreds of trackways, e.g.11,12,13,14.

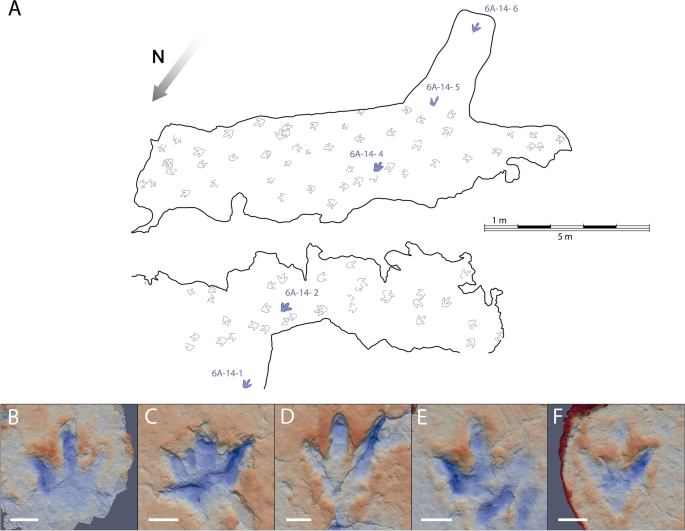

Walking is the most common behaviour inferred from dinosaur fossil trackways9,10,11,15, although some minor cases of running or trotting have also been identified13,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. Indeed, 96% of the 1802 Kayentapus dinosaur strides studied by Weems 13 were made by animals with a walking behaviour, whereas just 4% of them were made by dinosaurs with a more energetic way of movement. Of this 4%, the great majority is consistent with trotting displacement, whereas just one of the trackways could correspond to a running behaviour13. In the Early Cretaceous of Spain, a theropod trackway of six consecutive footprints with pace lengths of more than two metres preserved in a trampled surface was found at La Torre 6B (Igea, La Rioja)24 (Fig. 1), for which has been inferred high speeds of more than 10 ms−1 (Refs.25,26,27). The trackway from La Torre 6A was initially mentioned by Aguirrezabala et al.24 with the presence of two non-consecutive footprints and the probable presence of a third between them, lost by erosion. During new field campaigns in this area, two significant findings have recently been made: a new footprint was discovered to add to the La Torre 6B trackway, and the discovery of three new footprints in La Torre 6A that confirm the presence of a second high-speed trackway in La Torre tracksites. Both trackways shed light on locomotion, speeds and even behaviour of non-avian theropods.

Geographical and geological location of La Torre 6A and 6B tracksites. (A) Location of La Rioja in the Iberian Peninsula. (B) Geological map of the southern part of La Rioja, with the main stratigraphical groups differentiated. (C) Local stratigraphic succession of the study area (modified from Isasmendi et al.28).

Results and discussion

Tracks and trackways

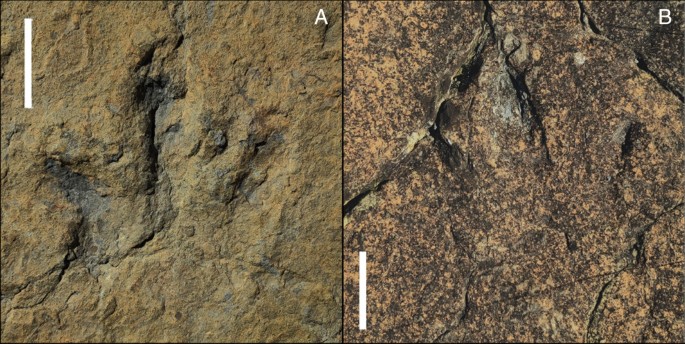

The La Torre 6A-14 trackway (Fig. 2) preserves only five of the six footprints because the third footprint in the trackway was at a point of the tracksite where the top layers of rock have been lost. The footprints are tridactyl, functionally mesaxonic, and longer than wide (mean length and width, respectively, of 32.8 cm and 30.2 cm). The footprints show well-preserved digit impressions (Fig. 3A). The divarication angle between the digit II and IV impressions is about 67° and varies from 57° to 75°. The metatarsophalangeal area is very shallow in the first footprint and elongated in footprints 2, 4 and 6. The impression of digit II is always deeper than digit IV, and in footprints 2 and 4 a sharp longitudinal groove is preserved, probably related to the claw imprint. The digit III impression also shows a deep area in its distal zone, but the claw imprint is at a higher level than the rest of the digit. In footprint 6, the posterior area of digit III is preserved as a narrow and shallow groove. Pad imprints are identified in footprints 2, 4, and 5. The impression of digit IV is elongated, has a sharp distal end, and is the shallowest of all digits. The mean values for the pace angulation, stride length and pace length are 169°, 523 cm and 265 cm, respectively.

CONTINUE READING HERE