By Graham Matthews

Published 27 July, 2024

I would like to acknowledge the work of the late Marta Russell, a Marxist and person living with disability, particularly the framework for understanding capitalism and disability that she outlines in her works, notably Beyond Ramps: Disability at the End of the Social Contract.1

When considering the politics of disability under capitalism, it is important to understand the economic aspects of the relationship between people’s disability and the means of production. Or how we, as people with disability, interact with society (as producers and consumers) and are valued (or not).

What is disability?

The first step is to define disability.

The medical model of disability normalises the able-bodied, fit, healthy, white male heterosexual adult as the ideal. This person is the archetype and anybody who does not reflect their characteristics (gender, sexuality, ethnicity, health and ableness) is considered somehow inferior. People with disability are a case in point: by definition we are not as able as the ideal person, do not contribute (as much) to the economic wealth of capital and, in many cases, need support to participate in society.

The social model of disability is person-centred and places responsibility for disability squarely at the feet of capital and the state, rather than the individual with disability. It says disability is caused by the way society is organised, rather than a person’s impairment or difference. When barriers are removed, people with disabled can be independent and equal in society, with choice and control over our lives.2

Before I delve into the political economy of capitalism and disability, I want to briefly touch on how people with disability were treated in pre-capitalist societies.

Pre-capitalist societies

In 2003, Mutthi Mutthi woman Mary Pappin Junior discovered fossilised footprints in the Mungo National Park. The tracks, estimated to date back 20,000 years, are the oldest found in Australia. They show footprints of three hunters running across the clayplan chasing a kangaroo. There is also a fourth set of tracks left by a one-legged man running across the claypan, possibly without the use of a stick or crutch.3 The fact this one-legged man was integrated into traditional Aboriginal society, 20,000 years ago, is more than a simple curiosity.

That this person, who might be considered “disabled” or even “crippled” in contemporary society, was participating in the subsistence economy (a hunt) is significant. It suggests that, at least in Aboriginal pre-class society, persons with even significant impediments were integrated into community life in a more or less natural way and were expected and permitted to participate in, and contribute to, society in whatever way they could. The footprints appear to provide evidence that pre-class society did not necessarily segregate, discriminate against, or otherwise persecute members with significant impediments.

From a Marxist point of view, this has particular significance in our understanding that the goal of history (Communist society) is a return to the kind of social equality experienced during pre-class society, but at a higher level.4 The fossilised footprints found at Lake Mungo evidence pre-class equality also extended to persons with significant impediment. This reinforces the need to return to that state of social equality, including for people with disability.

Rise of capitalism

Impediment has existed throughout history and class society. But prior to the emergence of capitalism, it was a part of the social fabric. There is evidence that people with disability were integrated into feudal society and made a contribution based on their abilities.5 Charity was provided by the Church for those physically disabled and no longer able to make a contribution. Even the famed Joan of Arc, who rose from obscurity to lead the French armies in the 100 Years War and was ultimately Sanctified by the Catholic Church, may have suffered from schizophrenia or epilepsy.6

Karl Marx wrote rather poetically in Capital Volume 1 that “capital comes dripping from head to toe, from every pore, with blood and dirt.”7 With the rise of capitalism, the productive class — the class that works and produces value — was “liberated” from the means of production. Enclosures and legislation separated peasants from their means of subsistence, both physically and geographically, leading to mass migration to the city.

The new working class was forced to sell its labour power to afford the means of life. Broadly, if you could not find work for the capitalists, you starved. However, the factory system — and later industrial capitalism — required intense concentration, dexterity and repetitive movement. Long hours, fine detail and intense concentration are not necessarily skills possessed by all people with disability.

So, they were largely excluded from the capitalist mode of production, including those injured by the system itself. Instead, people with disability joined the ranks of the unemployed — the reserve army of labour. If they did find work, it was generally transitory, poorly paid and very insecure. Impoverished, uncertain and limited subsistence necessarily followed.

The rise of capitalism meant the breakdown of social bonds (prominent within feudalism), and with it the privatisation of responsibility for disability within the family (women) or, at the extremes, institutionalisation and segregation.

Early gains

As early as 1848, Marx and Friedrich Engels acknowledged that class struggle compelled the working class to organise: “This organisation of the proletarians into a class… rises up again, stronger, firmer, mightier. It compels legislative recognition of particular interests of the workers, by taking advantage of the divisions among the bourgeoisie itself…”8 Organisation eventually won limited social gains for working people, including limited pensions, initially for soldiers unable to fight owing to physical disability, but later generalised.

In Australia, the winning of pensions for people with disability was part of the class settlement of the Federation of the Australian States in 1901. Section 51 of the Australian Constitution gives the Australian state power to legislate for so-called invalids. Significantly, the same section also allows the state to legislate for the Age Pension.

Both the Age and Invalid pensions were introduced in 1908. The Invalid Pension (later the Disability Support Pension, DSP) initially supported critically injured workers unable to provide for their families. Its scope was later broadened to provide some level of guaranteed economic support to others with disability. Similar pensions were introduced in a number of European countries around the same time.

War, revolution, crisis and reaction

The early 20th century began a period of war, revolution, economic crisis and reaction. A series of minor imperialist conflicts and struggles for national liberation culminated in World War I. In 1917, the workers and peasants of Russia overthrew the old regime and attempted to build a socialist society.

The settlement of World War I lay the foundations of a significant economic crisis (the Great Depression). In western Europe, this led to the rise of fascism: the bourgeois extreme reaction to economic crisis and a last-ditch attempt to head off revolution. The apex of that reaction was the rise of the Nazis in Germany in 1933.

The Nazi regime introduced systematic discrimination against people with disability, who were dehumanised and dismissed as “useless eaters” or “oxygen thieves”, in a way reminiscent of the dehumanisation of Jewish people as “rats”.

Soon after the Nazi’s ascension, “mercy” killings by doctors of children with disability began to take place. Twinned with segregation came confinement into institutions. However, institutionalisation of people with disability costs money and came to be seen as a burden on the state.

Beginning in 1939, the “solution” identified by the Nazis — one I am sure many of today’s neoliberals would be envious of — was the systematic murder of institutionalised people with disability. This was known as Aktion 41 and included the development of techniques later used in the death camps against Jews and others. “Showers” using poisonous gas (carbon monoxide) were developed to murder people with disability on an industrial scale.9 The state reduced its costs through the systematic murder of people with disability. While this was formally stopped in 1941, the killings, particularly of children with disability, continued alongside the wholesale murder of Jews and others.

Fascism is an extreme version of capitalism, one that the bourgeoisie is very reluctant to release except in periods of existential crisis. Nonetheless, it is a capitalist response to crisis — one that caused the death of millions, including more than 6 million Jews, during the Holocaust. While not characteristic of “democratic” capitalism, it is a historical fact that those dedicated to making a better world must not forget.

Civil rights and disability

World War II was not the last word in social development. Foment around the Vietnam War and social movements for the rights of women, LGBTQ+, Blacks, Indigenous nations and people with disability began to develop from the late 1960s.

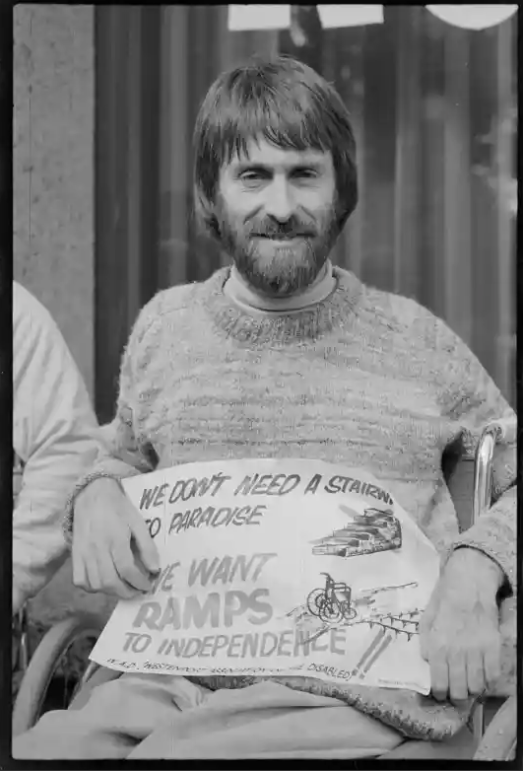

The 504 Sit-in in San Francisco in April 1977 was perhaps the first acknowledged disability rights demonstration. People with disability staged a sit-in to demand greater accessibility and better accommodation.10 A similar movement developed in Australia in the late 1970s. In April 1978, Disabled People’s Action Forum members blockaded a Medibank claims office with placards that read: “We don’t need a stairway to paradise, We want ramps to independence.”11

Pressure for the extension of civil rights to people with disability continued to grow, with the United Nations declaring 1981 the International Year of Disabled Persons. On November 10, 1981, 300 people with intellectual disabilities and their supporters rallied outside NSW Parliament to demand control over their housing and living conditions.

Formal rights but ongoing exclusion: The 1992 Disability Discrimination Act

In 1992, the Paul Keating Labor government passed the federal Disability Discrimination Act. However, more than 30 years after this formal acknowledgement of the rights of people with disability, the gains won have been limited and remain tenuous.

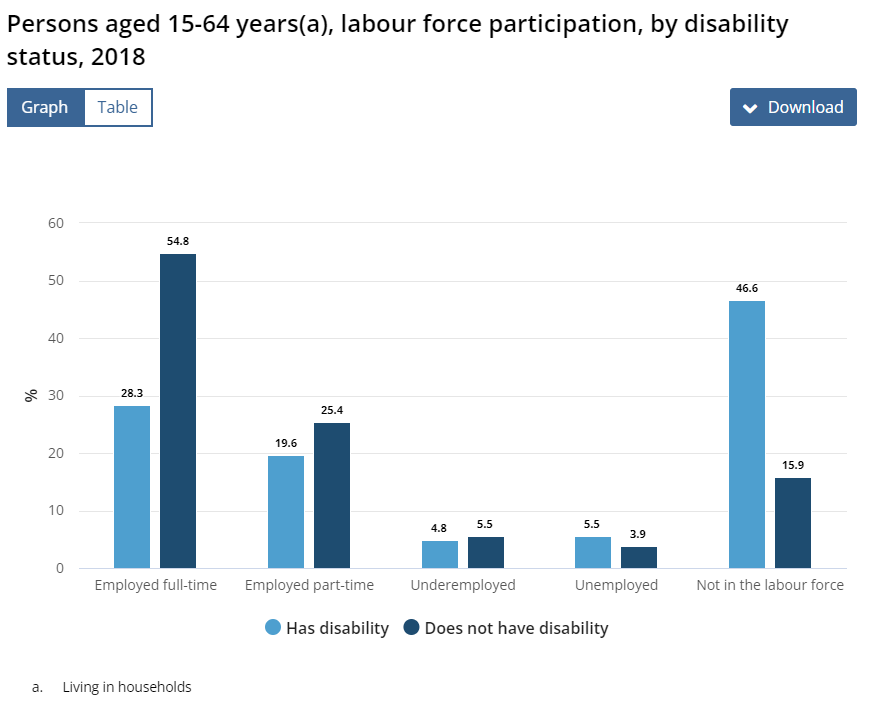

Independence and self-determination in a capitalist society are based on the ability to perform a job and be paid a living wage to support oneself (including rent, food, transport and entertainment). People with disability are significantly underrepresented in the workforce. Just over 2 million people with disability are of workforce age (15-64), according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). But around 1 million of those are not in the workforce. So if 46.6% of working-age people with disability are not in the workforce, where are they and how do they live?

The DSP is an important provision for people with disability who are unable to work (or at least to work full-time). It is a guaranteed income (albeit at poverty level) that proves some level of financial independence. But now that people with disability have the right to work, we also have “the right” to be excluded from income support. Despite there being more than 1 million working-age people with disability who are not in the workforce, only 649,000 are on the DSP. So, what of the other 350,000 who neither work nor receive the DSP. How do they live?

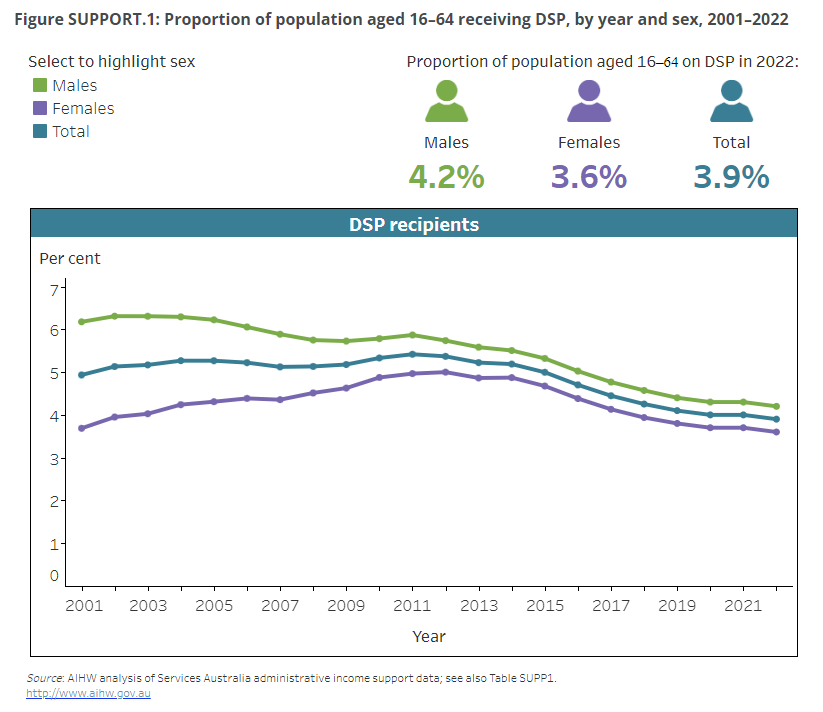

The drive to remove people with disability from the DSP (in many cases forcing them to live on the much lower Job Search Payment) is a central part of the neoliberal drive to reduce social subsidies, privatise the cost of support and force responsibility onto the family, all under the guise of independence. It has been pursued with gusto by both Labor and Coalition governments.12 Data from the federal government’s Institute of Health and Welfare demonstrates the proportion of working-aged people on the DSP is in significant decline, as older recipients are moved to the Aged Pension while significantly fewer new recipients are enrolled.

In more ways than one, people with disability are the new “dole bludgers”: suspected of receiving social support without good reason, and viewed as a drain on the public purse.

NDIS: Commodifying the disabled body

The Julia Gillard Labor government legislated to bring in the National Disability Insurance Scheme NDIS) in 2013. From the beginning, NDIS was a privatisation exercise. It gives huge government subsidies to private businesses to provide support for (some) people with disability. NDIS has led to a massive concentration of capital in the disability sector, with large corporations dominating the provision of services in metropolitan centres while people with disability struggle to find support in rural and regional areas. Increasingly, people with disability are supported only where it is profitable to do so.

The limitations, inequities and frustrations of NDIS are well documented, including in Green Left. However, there are aspects of NDIS that socialists and supporters of the rights of people with disability should defend, such as the lack of means testing.

Within NDIS, there are elements of self-determination for people with disability (including giving participants the limited right to decide who they want to support them and in what way). We should defend the democratic aspects of NDIS: the focus on social inclusion and independent aspiration (“goals”). People with disability are individuals with a wide range of wants, needs and desires. At its best, NDIS provides assistance to achieve at least some of these.

However, the universality and applicability of NDIS is under attack from the Anthony Albanese Labor government. We need to oppose “robo-planning”, which would reduce funded support to a number generated by a formula rather than individual needs, and any plan to introduce copayments. We should also oppose cuts to NDIS funding and to the range of people considered disabled enough to receive.

Beyond capitalism

Capitalism is intended to maximise wealth concentration in an increasingly dwindling number of hands. For the majority of us, it is only our labour power that separates us from penury. For people with disability, many of whom are not able to work — at least not for a living wage — the situation can be worse.

Socialists understand that only a coalition of the oppressed has the social power to overturn the rule of the minority and establish a society based on social equality. To bring about that change, this coalition must represent the aspirations and needs of all oppressed people, including people with disability.

This article is based on Graham Matthew’s presentation to Ecosocialism 2024. Matthews is a disability rights activist, Socialist Alliance founding member and regular Green Left contributor.

- 1

Marta Russell, Beyond Ramps: Disability at the End of the Social Contract, Maine: Common Courage Press, 1998

- 2

Social model of disability - People with Disability Australia (pwd.org.au)

- 3

- 4

Karl Marx’s Dialectical Historicism – Discourses on Minerva (minervawisdom.com)

- 5

Marta Russell, "Capitalism and Disability", Socialist Register 2002

- 6

Joan of Arc–Hearing Voices | American Journal of Psychiatry (psychiatryonline.org)

- 7

- 8

- 9

“Nazi and American Eugenics, Euthanasia, and Economics,” in Beyond Ramps

- 10

- 11

People With Disability Australian Protest Timeline - The Commons (commonslibrary.org)

- 12

Access to disability pension slashed by more than half, data shows | Welfare | The Guardian