Review of The Armed Strike: The Long London Exile of 1900—13. The Complete Works of Errico Malatesta. Vol. V. (2023). by Wayne Price

The Italian Errico Malatesta (1853—1932) was a comrade and friend of Michael Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin. Calling himself an anarchist-socialist, he was respected and loved by large numbers of anarchists and workers, in Italy and other countries. He was closely watched by the police forces of several nations. He had escaped imprisonment in Italy and lived in various countries in Europe, the Middle East, the U.S.A., and Latin America. Four times he spent time in Britain. This volume has collected works from his longest stay there, from 1900 to 1913, from when he was 48 to 61.

Britain, secure in its wealth and imperial power, was the most open European country in providing asylum to political refugees—so long as they obeyed local laws. As a result, the UK had communities of anarchists and other socialists from all over Europe. There was also an overlapping colony of Italians. Malatesta lived in London, supporting himself by running a small electrician’s shop. Only at one point, in 1912, did the police and courts make a serious effort to expel him. This set off massive demonstrations of British and immigrant workers and outcries from liberal newspapers and politicians. The attempt at expulsion was dropped.

However, Malatesta was frustrated by being penned up in Britain. He made several efforts to produce an anarchist-socialist paper which would circulate in Italy, but with limited success. He participated in anarchist activities in Britain, but his English, while apparently serviceable, was not fluent (when not speaking Italian, he preferred French). This volume includes his translated articles, pamphlets, and written speeches, as well as interviews of him by both bourgeois and radical newspapers. There are also reports by police spies (at least one of whom passed as a close comrade). They faithfully recorded his speeches and private comments and passed them on to their superiors.

In the course of Malatesta’s lengthy sojourn in London, he discussed a number of topics which were important to anarchists then and are still important. He was not an major theorist of political economy or history, but he was brilliant about strategic and tactical issues of the anarchist movement. This makes the study of Malatesta’s collected work valuable even today.

Terrorism

Around the time the book begins, in 1900, an Italian anarchist who had been living in the U.S., went back to Europe and assassinated Humbert, the Italian king. Apparently Malatesta had met the assassin, Bresci, briefly while in Patterson NJ. Otherwise he knew nothing about the affair. However the press continually tried to interview him about it, seeking to tie anarchism to assassination.

Malatesta always opposed indiscriminate mass terrorism (such as throwing bombs into restaurants). Nor did he call for assassination of prominent individuals, whether kings, presidents, or big businesspeople. In general, it did not advance the cause. His approach had become one of building revolutionary anarchist organizations, to participate in mass struggles. However, he was understanding of the motives of individual anarchists driven to assassination—and not sympathetic at all to the rulers and exploiters whom they killed. The Italian king, he noted, had previously ordered soldiers to massacre peasants and workers.

When US President William McKinley was shot dead by Czolgosz, who claimed to be anarchist, Malatesta called the president, “the head of [the] North American oligarchy, the instrument and defender of the great capitalists, the traitor of the Cubans and Filipinos, the man who authorized the massacre of the Hazelton strikers, the tortures of the Idaho miners and the thousand disgraces being committed in the ‘model republic.’” (Malatesta 2023; p. 75) He felt no sorrow for the death of this man, only compassion for the assassin, who “with good or bad strategy,” sacrificed himself for “the cause of freedom and equality.” (p. 75)

However, he did not advocate this as a political strategy. It was more important to win workers to reliance upon themselves rather than kings, bosses, and official leaders. “…Overthrowing monarchy…cannot be accomplished by murder. The Sovereigns who die would only be succeeded by other Sovereigns. We must kill kings in the hearts of the people; we must assassinate toleration of kings in the public conscience; we must shoot loyalty and stab allegiance to tyranny of whatever form wherever it exists.” (p. 59)

In another incident in London, a small group of Russian anarchist exiles was interrupted in the process of robbing a jewelry store. There was a shoot-out with the police (led by Home Secretary Winston Churchill) which ended in the death of some officers and all the robbers. As it happened, one of the thieves had met Malatesta at an anarchist club, and ended up buying a gas tank from him, claiming a benevolent use for it. In fact it was used to break open the jewelry safe.

Malatesta patiently explained to the police and the newspapers that he had no foreknowledge of the robbery. However he wrote that it was unfair to link the robbers’ actions with their anarchist politics. Was a murder in the U.S. blamed on the murderer being a Democrat or Republican? Were thieves’ thievery usually ascribed to their opinions on Free Trade versus Tariffs? Or perhaps their belief in vegetarianism? No, they were essentially regarded as thieves, regardless of their beliefs on politics, economics, or religion. The same should be true for these jewelry thieves, whatever their views on anarchism.

Syndicalism/Trade Unionism

By the last decades of the 19th century, many anarchists had given up on only actions and propaganda by individuals and small groups. These tactics had mainly resulted in isolation and futility. Instead many turned toward mass organizing and the trade unions. Anarchists joined, and worked to organize, labor unions in several countries. (Often these efforts were called “syndicalism,” which is the French for “unionism.”)

There remained anarchists who opposed unions: individualists and anti-organizational communists. But most turned in the pro-union direction. This gave a big boost to the anarchist movement at the time.

Errico Malatesta had long been an advocate of unions. He had contacts with militant unionists throughout Britain and other countries. In London in this period, he directly participated in unionizing waiters and catering staff. He gave support to the struggles of tailors to form a union, which led to a large strike.

“Syndicalism, or more precisely the labor movement…has always found me a resolute, but not blind, advocate.…I see it as a particularly propitious terrain for our revolutionary propaganda and…a point of contact between the masses and ourselves.” (p. 240)

But once it was decided that anarchists should participate in the labor movement, the next question was how should they participate? What should be the relation between anarchist activists and the trade unions? On this question, differences among anarchists were made explicit at the 1907 anarchist conference held in Amsterdam.

At the conference, Malatesta took issue with the views of Pierre Monatte, who spoke for the French syndicalist movement. Malatesta argued, “The conclusion Monatte reached is that syndicalism is a necessary and sufficient means of social revolution. In other words, Monatte declares that syndicalism is sufficient unto itself. And this, in my opinion, is a radically false doctrine.” (p. 240)

The unions had great advantages, as they brought together working people in enterprises, industries, cities, and regions. They included only workers, and not capitalists or management. They had the potential of stopping businesses and whole economies, in the pursuit of working class demands. They were schools of cooperation and joint struggle.

Yet, the unions’ very strengths also pointed to certain weaknesses. They are institutions within capitalist society. They exist (at least in the short term) to win a better deal for the workers under capitalism. Therefore they must compromise with the bosses and the state. Further, they need as many members as possible, to counter the power of the bosses. They cannot just recruit revolutionary anarchists and socialists. They must take in workers of every political, economic, and religious persuasion. (A union which only accepted anarchists would not be much of a threat to the bourgeoisie.)

These and other factors brought constant pressure on unions to be more conservative, corrupt, and bureaucratic. All anarchists recognized these tendencies among officials of political parties, even among liberals or socialists. But the same tendencies existed for union officials.

Malatesta drew certain conclusions. Anarchist-socialists should not dissolve themselves into the unions, becoming good union militants (as he understood Monatte to be saying). Instead, they should build revolutionary anarchist groups to operate inside and outside union structures. Nor should they take union offices which gave them power over people. But they could take positions which were clearly carrying out tasks agreed to by the membership—but with no wages higher than the other workers. They should be the best union militants, always advocating more democratic, less bureaucratic, and more militant policies, while still raising their revolutionary libertarian politics.

“In the union, we must remain anarchists, in the full strength and full breadth of the term. The labor movement for me is only a means—evidently the best among all means that are available to us.” (p. 241)

A central concept of the syndicalists was the goal of a general strike. Malatesta had certain criticisms. Not that he opposed the idea of getting all the workers of a city or country to go on strike at the same time. This could show the enormous power of the working class, if it would use it—much more powerful than electing politicians. But there is no magic in a general strike. The capitalist class has supplies stored away with which they could outlast the workers—starve them out. The state has its police and armed forces to break up the strike organization, arrest the organizers, and forcibly drive the workers back to their jobs.

In brief, Malatesta did not believe in the possibility of a successful nonviolent general strike (this is not considering a one-day “general strike” set by the union bureaucrats for show). He felt that a serious general strike would require occupation of factories and workplaces, arming of the workers, and plans for their military self-defense. It would have to be the beginning of a revolution. (Hence the book’s title.)

However much he criticized aspects of syndicalism, Malatesta was completely opposed to “…the anti-organizationalist anarchists, those who are against participation in the labor struggle, establishment of a party, etc. [By ‘party,’ he means here an organization of anarchists—WP] ….The secret of our success lies in knowing how to reconcile revolutionary action and spirit with everyday practical action; in knowing how to participate in small struggles without losing sight of the great and definitive struggle.” (p. 78)

War and National Self-Determination

This collection of writings by and about Malatesta ends in 1913. Therefore it does not cover his response to World War I which began the next year—nor his break with Kropotkin for supporting the imperialist Allies in the war.

However, in the period covered here, he could see the increase in wars, both between imperialist powers and between imperial states and oppressed peoples. “…Weaker nations are robbed of their independence. The kaiser of Germany urges his troops to give the Chinese no quarter; the British government treats the Boers…as rebels, and burns their farms, hunts down housewives…and re-enacts Spain’s ghastly feats in Cuba; the Sultan [of Turkey] has the Armenians slaughtered by the hundreds of thousands; and the American government massacres the Filipinos, having first cravenly betrayed them.” (p. 33)

He opposed all sides in wars among imperialist governments—as he was to do during World War I. The only solution to such wars was the social revolution.

But Malatesta supported oppressed nations which rebelled against imperial domination. (Some ignorant people believe that it is un-anarchist to support such wars. Yet Malatesta did, as did Bakunin, Kropotkin, Makhno, and many other anarchists—even though they rarely used the term “national self-determination”.) Malatesta wrote, “…True socialism consists of hoping for and provoking, when possible, the subjected people to drive away the invaders, whoever they are.” (p. 58)

This does not mean that anarchist-socialists have to agree with the politics of the rebelling people. Speaking of the Boers, who were fighting the British empire, he wrote without illusions, “The regime they will probably establish will certainly not have our sympathies; their social, political, religious ideas are the antipodes of our own.” (p. 59) Nevertheless, it would be better if they win and British imperialists are defeated. For the people of the imperialist country, “It is not the victory but the defeat of England that will be of use to the English people, that will prepare them for socialism.” (p. 58) (The British won.)

The Italian and Turkish states went to war over north Africa around 1912. Malatesta condemned both sides, but supported the struggle of the Arab population. “I hope that the Arabs rise up and throw both the Turks and the Italians into the sea.” (p. 321)

He understood that “love of birthplace” (p. 328) was typically felt by people, including their roots in the community, their childhood language, their love of local nature, and perhaps their pride in the contributions their people have made to world culture. But this natural sentiment is then misused by the rulers to develop a patriotism which masks class division and exploitation.

The rulers “…turned gentle love of homeland into that feeling of antipathy…toward other peoples which usually goes by the name of patriotism, and which the domestic oppressors in various countries exploit to their advantage. ….We are internationalists…We extend our homeland to the whole world, feel ourselves to be brothers to all human beings, and seek well-being, freedom, and autonomy for every individual and group…..We abhor war…and we champion the fight against the ruling classes.” (p. 329)

As can be seen, to Malatesta, internationalism did not conflict with support for “autonomy for every…group.” This included groups of people who held a common identity as a nation. Anarchists are internationalist, but

unlike the centralism of Lenin, anarchists do not want a homogenous world state. They advocate regionalism, pluralism, and decentralized federations. This particular passage went on to support the Arabs against Italian imperialism. “…It is the Arabs’ revolt against the Italian tyrant that is noble and holy.” (p. 329)

Yet Malatesta may be faulted for his lack of concern about racism. In supporting the Boers, and even when listing their extreme (antipodal) differences with anarchists, he does not mention their exploitation of the indigenous Africans. Nor does he make other references to racial oppression (such as in U.S. segregation). This must be put beside his fervent anti- colonialism and support for the rebellion of oppressed peoples.

Similarly, he does not mention the oppression of women or its intersection with class and national exploitation. It is not at all that he was misogynist (like Proudhon). I am sure he treated Emma Goldman as an equal at the 1907 international anarchist conference. But, like most male radicals of his time, he had a “blind spot” in thinking about this major aspect of overall oppression.

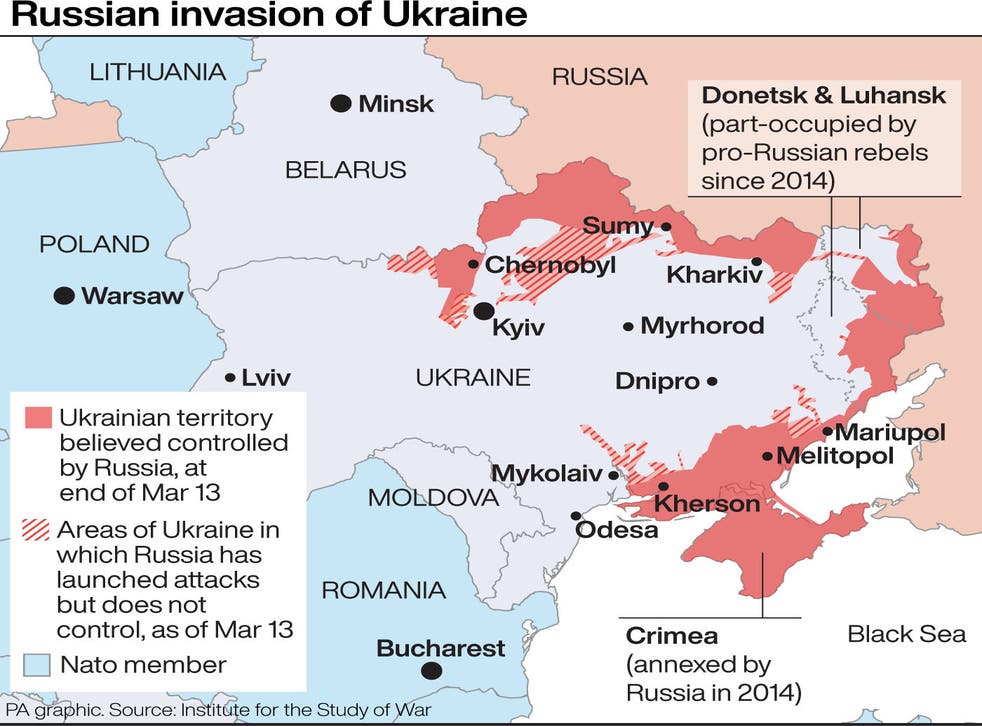

Imperialism, war, national oppression, and national revolt are issues which are still with us. Look at Palestine or Ukraine or the Kurds, among other peoples. These issues will be with us as long as capitalism survives, as Malatesta knew.

Other Topics

Besides terrorism, syndicalism, and national wars, Malatesta covered quite a lot of topics in the course of these thirteen years, as we would expect.

He condemned a French anti-clerical town council which outlawed the wearing by priests of their cassocks within the municipal borders. Malatesta was an opponent of religion and certainly of the Catholic Church. But he did not believe that people would be won from it by means of police coercion. That would only provoke resistance. At most, it would replace the religious priests with secularist ones, “which would all the same preach subjugation to masters….” (p. 68)

Today, the French government forbids Muslim girls and women from wearing headscarfs in schools and other public buildings—in the name of “secular” government. The left and feminists are divided on how to respond. “Oh, when will those who call themselves friends of freedom, decide to desire truly freedom for all!” (p.68)

Unlike Kropotkin, Elisee Reclus or (more recently) Murray Bookchin, there was not much of an ecological dimension to Malatesta. However he was concerned with the way landlords and capitalists had kept Italian agriculture backward. He believed that under anarchy, the peasants would be able to make the barren lands bloom.

By 1913, his experience with state socialists was mainly with the reformist Marxist “democratic socialists” (social democrats). This was four years before the Russian Revolution, which ended in the dictatorship of Lenin’s Bolsheviks and the rise of authoritarian state capitalism.

Yet he was prescient enough to write: “…Depending on the direction in which competing and opposite efforts of men and parties succeed in driving the movement, the coming social revolution could open to humanity the main road to full emancipation, or simply serve to elevate a new layer of the privileged above the masses, leaving unscathed the principle of authority and privilege.” (p. 102) The validity of this anarchist insight (which goes back to Proudhon and Bakunin) has been repeatedly demonstrated.

All the subjects Errico Malatesta discussed in this period had one guiding social philosophy. Quoting the famous lines written by, but not created by, Marx: “…The emancipation of the workers must be conquered by the workers themselves.…Throughout history the oppressed have never achieved anything beyond what they were able to take, push away pimps and philanthropists and politicos, take their own fate in their own hands, and decide to act directly.” (p. 220) This was the principle of Malatesta’s revolutionary anarchist-socialism and remains true today.

References

Malatesta, Errico (2023). The Armed Strike: The Long London Exile of 1900—13. The Complete Works of Errico Malatesta. Vol. V. (Ed.: Davide Turcato; Trans.: Andrea Asali). Chico CA: AK Press.

Khrystiuk was a Central Committee member of the million strong Ukrainian Party of Socialist Revolutionaries (UPSR) and a deputy in the autonomous parliament the Central Rada, he held positions in the Ukrainian Peoples Republic and later he worked for the Society of Scientific and Technical Workers for the Promotion of Socialist Construction Kharkiv. A publisher of several studies Khrystiuk was arrested in 1931 and perished in the Stalinist terror in a in a Soviet

Khrystiuk was a Central Committee member of the million strong Ukrainian Party of Socialist Revolutionaries (UPSR) and a deputy in the autonomous parliament the Central Rada, he held positions in the Ukrainian Peoples Republic and later he worked for the Society of Scientific and Technical Workers for the Promotion of Socialist Construction Kharkiv. A publisher of several studies Khrystiuk was arrested in 1931 and perished in the Stalinist terror in a in a Soviet