HAMBURG, May 2 (Reuters) - Russian attacks on Ukraine's grain infrastructure look like attempts to reduce the competition in Russia's export markets, German Agriculture Minister Cem Oezdemir was reported as saying on Monday.

Ukraine could lose tens of millions of tonnes of grain due to Russia's blockade of its Black Sea ports, triggering a food crisis that will hit Europe, Asia and Africa, President Volodymyr Zelenskiy said on Monday.

“We are repeatedly receiving reports about targeted Russian attacks on grain silos, fertilizer stores, farming areas and infrastructure,” Oezdemir was quoted as telling the Redaktionsnetzwerk Deutschland, a cooperation network of German regional newspapers.

Russia denies targeting civilian areas.

The suspicion is growing that Russian President Vladimir Putin is seeking “in the long term to remove Ukraine as a competitor”, Oezdemir was quoted as saying.

Russia and Ukraine are traditionally major competitors in global grains markets. Global wheat prices have risen about 40% since Russia’s Feb. 24 invasion of Ukraine cut supplies available on world markets from the Black Sea.

According to International Grains Council data, Ukraine was the world's fourth-largest grain exporter in the 2020/21 season, selling 44.7 million tonnes abroad. The volume of exports has fallen sharply since the Russian invasion.

“With the increasing hunger in the world, Russia is seeking to build up pressure,” Oezdemir told the network. “At the same time, the massive increase in market prices is coming in handy for Russia because this brings new money into the country.”

Oezdemir said he would raise the question of how Ukraine could be helped to boost its grain exports at a meeting of G7 agriculture ministers in mid-May.

“We must seek alternative transport methods,” he said. “Railway transport could be a method of exporting more grain, although with much effort and with limited capacity."

Germany would seek to give assistance, he added.

Ukraine has been gradually expanding grain exports using land transport to the European Union. But the different rail track widths in Ukraine and the EU mean Ukrainian trains cannot automatically operate on the European rail network.

Moscow calls its actions a "special military operation" to disarm Ukraine and rid it of anti-Russian nationalism fomented by the West. Ukraine and the West say Russia launched an unprovoked war of aggression that threatens to spiral into a much wider conflict. (Reporting by Michael Hogan, editing by Nick Macfie)

Thomson Reuters 2022.

Ukraine says Russia is stealing grain, which could worsen food crisis

Claire Parker

Thu, May 5, 2022,

Ukrainian officials say that Russian forces have taken vast stores of grain from Ukraine and exported it to Russia, exacerbating the risk of shortages and hunger in areas under Russian control.

Farmers in Ukrainian territory occupied by Russian forces reported that the Russians were "stealing their grain en masse," according to a statement released over the weekend by Ukraine's Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food.

Subscribe to The Post Most newsletter for the most important and interesting stories from The Washington Post.

Agriculture minister Mykola Solskyi said on Ukrainian television last week that he had heard a surge of accounts from elevator operators of Russians seizing grain in recent weeks in occupied areas.

"This is outright robbery," he said, warning that the behavior could cause a food crisis.

One of the world's largest grain exporters, Ukraine has seen its grain industry hobbled by Russian attacks and blockades of sea ports that Ukraine relied on to transport food products to countries around the world. Countries in the Middle East and South Asia rely heavily on Ukrainian grain, and the United Nations World Food Program has warned that the war could exacerbate global hunger.

Ukrainian officials say hunger is a growing threat at home, too - and accuse Russia of deliberately seeking to prevent Ukrainians from consuming or selling their agricultural products.

Ukraine had 30 million tons of wheat in storage as of last month. Deputy agriculture minister Taras Vysotskiy said Thursday that Ukraine has enough food stocks in the parts of the country it still controls to feed the population there, Reuters reported. But in Russian-occupied territory, it may be a different story, officials warned.

Two months into its invasion, Russia controls swaths of southern Ukraine - a region that helped the country earn its reputation as the breadbasket of Europe. Vysotskiy said on Ukrainian television this week that the Russians had exported about 441,000 tons of grain from four occupied regions: Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, Donetsk and Luhansk.

Vysotskiy said 1.4 million tons of grain were stored in occupied territory and are needed for daily food needs of Ukrainians who live there.

More than 90 percent of farmland in Luhansk is concentrated in the northern part of the region, which Russian forces have taken over since February, Serhiy Haidai, the regional governor of Luhansk, said on his Telegram channel. The Russians removed or destroyed a quantity of grain in the region that would have met residents' needs for three years.

The Washington Post could not verify the accuracy of the claims. The U.N. World Food Program said it was was unaware of any grain seizures and exports by Russian forces in occupied areas of Ukraine.

The Kremlin denied Ukraine's allegations, according to Reuters.

Reports of Russian attacks on Ukrainian grain facilities have also mounted. Haidai accused Russia of attacking a grain elevator tons of grain in Rubizhne, a city in Luhansk, in April. Nearly 19,000 tons of wheat and about 9,400 tons of sunflower product was destroyed, he said. Earlier this week, the regional governor of Dnipropetrovsk shared a video of a rocket attack which he said destroyed a grain warehouse in the Synelnykove district.

Satellite images provided to The Washington Post by Planet Labs, a public Earth imaging company, taken on April 8 and April 21, show the elevator before and after the attack. In the April 21 image, the majority of the facility appears completely flattened.

The Kremlin has denied targeting civilian infrastructure.

German Agriculture Minister Cem Ozdemir has accused Russia, the world's top wheat exporter, of using the war in Ukraine to gain a competitive advantage on the export market.

"We keep getting reports about targeted Russian attacks on grain silos, fertilizer stores, farming areas and infrastructure," he told RedaktionsNetzwerk, a network of German regional newspapers, on Monday, adding that Russian President Vladimir Putin apparently aimed to "eliminate Ukraine as a competitor in the long term."

Ozdemir said Russia was trying to capitalize on growing world hunger.

Speaking to Fox News' Griff Jenkins on Wednesday, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky accused countries of making backroom deals with Moscow to buy grain "stolen from Ukraine." He did not name the countries.

If confirmed, the alleged grain seizures and attacks targeting grain facilities could fuel allegations of war crimes. International law prohibits pillaging places taken in war and intentionally starving civilians by depriving them of food and basic necessities.

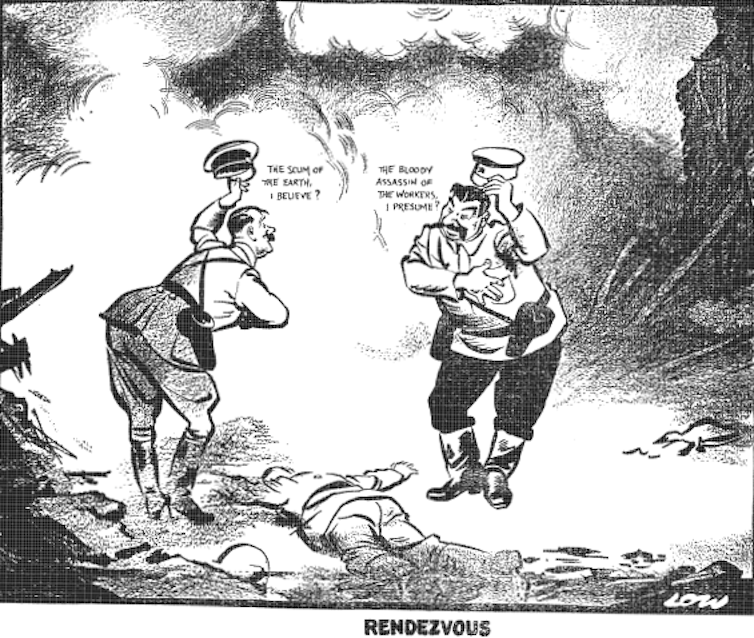

Ukrainian officials allege Russia is trying to cause a famine in Ukraine. Some have drawn parallels to the Holodomor, the famine engineered by Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin that killed about 4 million people in Ukraine in 1932 and 1933, mostly farmers and rural residents. While even the most serious of today's allegations hardly compare, the resonance runs deep, amid a conflict that has opened unclosed historical wounds.

Solsky, the agriculture minister, described alleged Russian pillaging of grain in recent weeks as reminiscent of the 1930s.

"The goal is the Holodomor," Haidai, the Luhansk governor, said after the grain elevator bombing in Rubizhne.

Ukrainian human rights ombudsman Lyudmila Denisova, in a Facebook post, repeated the comparison, and called the exportation of grain from occupied areas a violation of the Geneva Conventions.

The term invokes a horrific episode of cruelty from Moscow toward the Ukrainian people. During the Holodomor - which means death by hunger - Stalin sought to put down resistance to collectivization by blocking rural Ukrainians from accessing food. Some desperate Ukrainians resorted to cannibalism.

Historians widely describe the famine as deliberate Soviet policy. Raphael Lemkin, an international law expert who coined the term "genocide," called the Holodomor "the classic example of Soviet genocide."

Russia has blockaded Ukraine's Black Sea ports, preventing Ukraine from exporting grain and other agricultural products. Zelensky said Ukraine could lose tens of millions of tons of grain as a result of the blockade, telling Australian news program 60 Minutes that "Russia wants to completely block our country's economy."

Global food prices are already skyrocketing. Countries such as Egypt, Lebanon and Pakistan, which rely heavily on Ukrainian wheat, are likely to be hardest hit by export blockages.

Since the war began, Ukraine has sought other ways to transport wheat out of the country. Vysotskiy, the deputy agriculture minister, said the country had increased grain exports in April through these alternative routes, and that he expected another uptick in May.

But Ukraine can't export nearly as much wheat by train as by sea, and the World Food Program has warned that without functioning ports, the risk of famine around the world is growing.

- - -

The Washington Post's David Stern and Rick Noack contributed to this report.