Kropotkin’s theory of mutual aid remains cogent as ever, demonstrating the capacity for revolutionary change even in the harshest, most repressive environments.

AUTHOR

Ruth Kinna

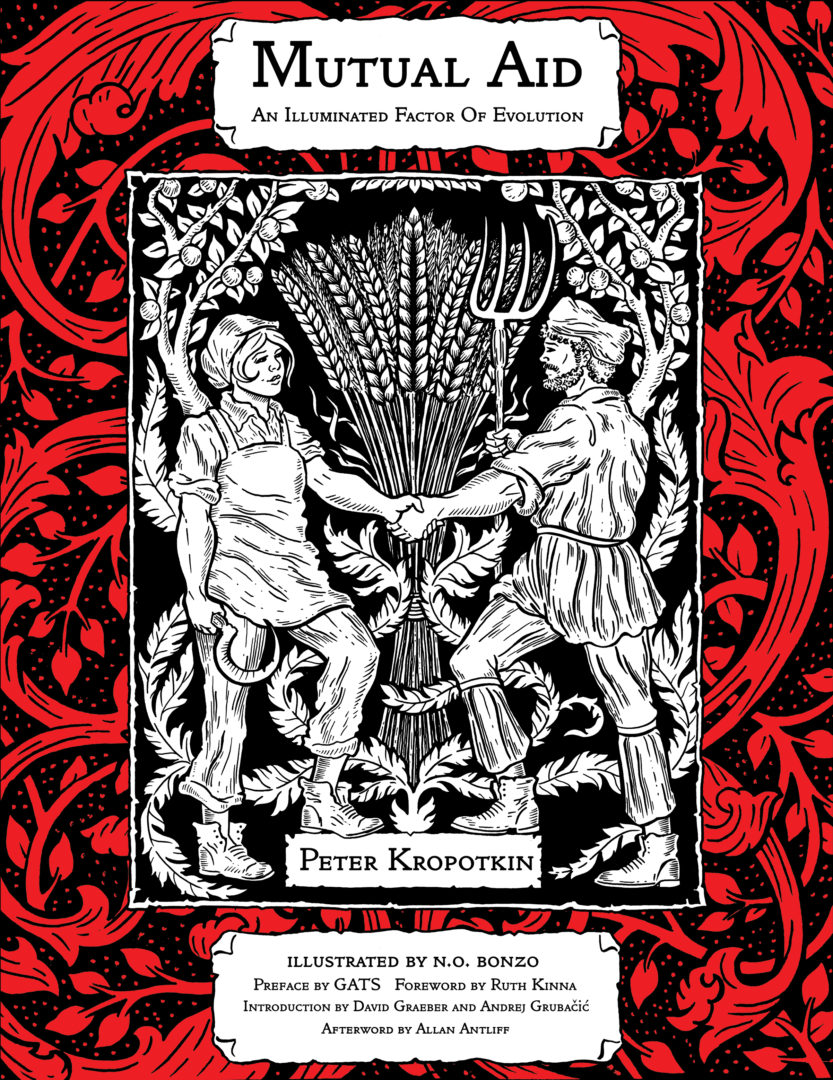

This is an abridged version of Ruth Kinna’s foreword to Kropotkin’s “Mutual Aid: An Illuminated Factor of Evolution” (PM Press, 2021).

Ruth Kinna

This is an abridged version of Ruth Kinna’s foreword to Kropotkin’s “Mutual Aid: An Illuminated Factor of Evolution” (PM Press, 2021).

February 8, 2021

In March 1889 Peter Kropotkin agreed to give six lectures to William Morris’s Socialist Society in Hammersmith, London. Labeling the series “Social Evolution,” he planned to explore “the grounds” of socialism. As it turned out, he never delivered the talks, but the title and timing, just a year before he published his first essay on mutual aid, hint at the content. He left a bigger clue when he told Morris’s daughter May that he had been working on the series during his recent tour of Scotland. According to local press reports, one of the issues on Kropotkin’s mind was the feasibility of socialism. Perhaps rashly, given that one critic had dismissed his socialism as a futile, dangerous scheme to “reach Arcady through anarchy,” he told an Aberdeen meeting that too many workers attracted to socialism still believed it impractical. The account of social evolution he outlined in Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, was a response to this skepticism and it has since become his most celebrated refutation.

The concept of mutual aid is outlined in eight essays. The first, “Mutual Aid Among Animals” was published in 1890 in the journal The Nineteenth Century. By 1896, Kropotkin had completed the others. The resulting book was published in 1902, but Kropotkin continued to develop the concept, notably in Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Ideal (1897), The State: Its Historic Role (1898), and Modern Science and Anarchism (1912). Some 30 years after starting his investigations, he issued his final, incomplete statement, which was posthumously published as, Ethics, Origin and Development (1924).

Each new iteration brought out a different facet of the concept: the repressive character of the modern European state; the impulses driving exemplary behaviors; the basis of moral action; the principle of justice that morality described and, last not least, the structural mechanisms for its acculturation. The common thread tying these strands together was Kropotkin’s view that socialism tapped an innate tendency to co-operate common to all living things. Socialism was neither the utopists’ candy mountain nor the salvationists’ pie in the sky. It was a potential alternative.

The thrust of Kropotkin’s argument was that existing disciplinary, exploitative orders had institutionalized competition and individual struggle, wrongly presenting this behavior as natural. Against this, the theory of mutual aid demonstrated that there was nothing inevitable, preordained, much less moral or good about these arrangements. Nature was plastic and therefore malleable to forces capable of building convivial, libertarian social systems.

Mutual Aid lends itself to multiple interpretations. This is partly because Kropotkin theorized it by intervening in a long-standing debate about the social and ethical implications of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species. In doing so, he enthusiastically adopted Victorian interdisciplinary conventions, reading across the arts and sciences to marshal evidence from zoology, history, art and newer disciplines, notably sociology, ethnography and anthropology, which were equally multifaceted. Ironically, since Kropotkin decried specialization, the synthetic quality of Mutual Aid has since enabled teams of scholars in the humanities and natural and social sciences to bring their special disciplinary perspectives to bear on it.

Since the publication of Daniel P. Todes’s pivotal essay in 1987, Mutual Aid is now commonly situated in a broader body of Russian evolutionary thought. But the diversity of the literature on it and the range of its conceptual resonances is vast. In the other part, Kropotkin developed critical Russian evolutionary biology to show how his account of Darwinian theory exposed the flaws in competing belief systems. Kropotkin believed the principle of mutual aid scotched Christian moralizing, utilitarianism, Marxist materialism and Nietzschean individualism. His naturalistic, “scientific” defense of anarchism thus lends itself to comparison with all these standpoints, while also nourishing critics interested in uncovering anarchism’s essentialist errors.

In March 1889 Peter Kropotkin agreed to give six lectures to William Morris’s Socialist Society in Hammersmith, London. Labeling the series “Social Evolution,” he planned to explore “the grounds” of socialism. As it turned out, he never delivered the talks, but the title and timing, just a year before he published his first essay on mutual aid, hint at the content. He left a bigger clue when he told Morris’s daughter May that he had been working on the series during his recent tour of Scotland. According to local press reports, one of the issues on Kropotkin’s mind was the feasibility of socialism. Perhaps rashly, given that one critic had dismissed his socialism as a futile, dangerous scheme to “reach Arcady through anarchy,” he told an Aberdeen meeting that too many workers attracted to socialism still believed it impractical. The account of social evolution he outlined in Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, was a response to this skepticism and it has since become his most celebrated refutation.

The concept of mutual aid is outlined in eight essays. The first, “Mutual Aid Among Animals” was published in 1890 in the journal The Nineteenth Century. By 1896, Kropotkin had completed the others. The resulting book was published in 1902, but Kropotkin continued to develop the concept, notably in Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Ideal (1897), The State: Its Historic Role (1898), and Modern Science and Anarchism (1912). Some 30 years after starting his investigations, he issued his final, incomplete statement, which was posthumously published as, Ethics, Origin and Development (1924).

Each new iteration brought out a different facet of the concept: the repressive character of the modern European state; the impulses driving exemplary behaviors; the basis of moral action; the principle of justice that morality described and, last not least, the structural mechanisms for its acculturation. The common thread tying these strands together was Kropotkin’s view that socialism tapped an innate tendency to co-operate common to all living things. Socialism was neither the utopists’ candy mountain nor the salvationists’ pie in the sky. It was a potential alternative.

The thrust of Kropotkin’s argument was that existing disciplinary, exploitative orders had institutionalized competition and individual struggle, wrongly presenting this behavior as natural. Against this, the theory of mutual aid demonstrated that there was nothing inevitable, preordained, much less moral or good about these arrangements. Nature was plastic and therefore malleable to forces capable of building convivial, libertarian social systems.

Mutual Aid lends itself to multiple interpretations. This is partly because Kropotkin theorized it by intervening in a long-standing debate about the social and ethical implications of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species. In doing so, he enthusiastically adopted Victorian interdisciplinary conventions, reading across the arts and sciences to marshal evidence from zoology, history, art and newer disciplines, notably sociology, ethnography and anthropology, which were equally multifaceted. Ironically, since Kropotkin decried specialization, the synthetic quality of Mutual Aid has since enabled teams of scholars in the humanities and natural and social sciences to bring their special disciplinary perspectives to bear on it.

Since the publication of Daniel P. Todes’s pivotal essay in 1987, Mutual Aid is now commonly situated in a broader body of Russian evolutionary thought. But the diversity of the literature on it and the range of its conceptual resonances is vast. In the other part, Kropotkin developed critical Russian evolutionary biology to show how his account of Darwinian theory exposed the flaws in competing belief systems. Kropotkin believed the principle of mutual aid scotched Christian moralizing, utilitarianism, Marxist materialism and Nietzschean individualism. His naturalistic, “scientific” defense of anarchism thus lends itself to comparison with all these standpoints, while also nourishing critics interested in uncovering anarchism’s essentialist errors.

EVOLUTION AND REVOLUTION

Revolutionary change was the natural counterpart to Kropotkin’s evolutionary social theory. Kropotkin’s proposals, outlined in The Conquest of Bread and Fields, Factories and Workshops, were to descale and federate. He imagined the commune as the basic social unit with a new political economy of needs based on the abolition of labor divisions, wage systems and international trade supported by the integration of agriculture and industry in localities. Mutual aid was the means and the object of this transformation. Anarchist communism was a model for “consensus” which required co-operation to bring it into being.

In the last two chapters of Mutual Aid, Kropotkin highlighted examples of co-operative practice to demonstrate that the capacity for change endured even in the harshest, most repressive environments. Some of these demonstrate the pervasiveness of the “psychology” of mutual aid, the irresistible feeling “nurtured by thousands of years of human social life and hundreds of thousands of years of pre-human life in societies”. Typically, it is expressed through acts of solidarity and sacrifice. For Kropotkin, it explained the motivations of volunteers in the British Lifeboat Association, who risked their lives at sea to save others from drowning. The same psychology drove Welsh miners to enter collapsed mine shafts for the sake of fellow-worker buried under tons of coal.

Other examples of co-operative practice, by far the majority, point to the importance of the organizational aspects of co-operation. Having described the dismal collapse of the city-states and its disastrous consequences, Kropotkin argued that there were significant holes in the state’s armor. The state exercised an increasingly tight grip on corporations, co-operative societies and associations that once flourished independently of it, but this was far from complete. Even in Europe, Kropotkin was pleased to discover that village community continued to exist. Europe was “covered with living survivals … and European country life is permeated with customs and habits dating from the community period”.

Mutual aid “customs and habits” animated he “inner life” of Turkish villages and, likewise, “in the Arab djemmâa and the Afgan purra, in the villages of Persia, India, and Java, in the undivided family of the Chinese, in the encampments of the semi-nomads of Central Asia and the nomads of the far North”. In colonized Africa, too, “notwithstanding all tyranny, oppression, robberies and raids, tribal wars, glutton kings, deceiving witches and priests, slave-hunters, and the like” the “nucleus of mutual-aid institutions, habits and customs, growing up in the tribe and the village community, remains.” Colonized peoples did not require preparation for self-government. They did not need the chiefs who had been empowered by colonizers to rule them or the rising class of local educated elites who sought to oust both to implement direct rule.

Kropotkin was similarly enthused by the new forms of co-operation and mutual aid vested in a plethora of cultural associations and, especially, socialist organizations and actions: syndicates, trade unions, strikes, political movements, newspapers. Some of these were outgrowths of traditional guilds or, in Russia artisan artéls and others were entirely modern manifestations of co-operation and solidarity, created to resist domination and exploitation.

Revolution entailed protecting, nurturing and extending these multifarious mutual aid organizations to facilitate the habitual expression of the psychology. As a global exercise, the project inescapably heightened diversity. In this respect, Kropotkin was neither a traditionalist nor a modernist. The co-operative associations contained within the naturalistic, self-regulating, ethical anarchy he conceptualized were complex, distinctive and adapted to their local environments. The practice of mutual aid bound them together, promising, too, to transform the “European” aspiration for international solidarity into a reality. Kropotkin’s message was that the only route to revolutionary change was the extension of the principle of self-government, not the spread of ideology or adherence to party program.

In Mutual Aid Kropotkin used his “anarchized” evolutionary theory to attack advocates of state order or “subordination.” While this included laissez-faire liberals and conservatives of all stripes, he promoted his concept of revolution to highlight the shortcomings of currents within socialist and anarchist movements. In the 1870s Michael Bakunin had identified republicans and Marxists as advocates of political theology, as antagonistic to anarchy as any absolutist or cleric. Kropotkin followed suit but identified Nietzscheans and Marxists and the leading advocates of competition and “subordination” liable to derail the socialist cause from within.

The problem with Nietzscheanism turned principally on the promotion of the concept of autonomy at odds with the psychology of mutual aid, though it also had an organizational aspect. For Kropotkin, Nietzscheans were individualists who followed bourgeois norms rather than anarchist principles of co-operation. Not only did they fail to understand the organizational dimensions of social transformation, they undermined the cohesion of the workers’ associations. In doing so, they destroyed grassroots initiatives to consider economic, political and moral questions “precursory” to revolutionary transformation, Kropotkin argued in his 1889 lecture “Socialism: Its Modern Tendencies.”

Writing to Alexander Berkman in 1908, he remarked, “[i]t is the Masses which make the Revolutions – not the Individuals”. Observing that European workers’ had “abandoned” groups after they had been “invaded by all sorts of middle class tramps,” he added, “even the really revolutionary minded individuals, if they remain isolated, turn towards this Individualist Anarchism of the bourgeois which is nothing but the epicurean let it go of the Economists, spiced with a few ‘terrific’ phrases of Nihilism.” This was “food to frighten the Philistines” and best left to “the Nietzsche’ists … Bernard Shaw’ists, and all the similar arch-Philistine‘ists’.”

If the Nietzscheans’ lofty dismissal of organization endangered the spread of mutual aid, the imposition of a singular model was at least as dangerous to the prospects of co-operation. This was the threat that Kropotkin believed came from Marxism. Writing only a year after the publication of the book, Kropotkin explained to Guillaume that the significance of the Mutual Aid was twofold: it challenged the faulty premises of the Social Darwinist thesis of competition and it demonstrated the tyrannous implications of the Marxist theory of history. The priority Marx attached to the development of productive forces as the prerequisite for socialist transformation implied the extension of the competitive model, not its abolition. Kropotkin told Guillaume, “their metaphysics is authoritarian.”

However elaborately Marxists conceptualized the state, their theory of socialist transformation was predicated on the destruction of traditional communal and co-operative associations. Russia was uppermost in Kropotkin’s mind when he wrote to Guillaume, but the implications of his analysis were more far-reaching. Marxism pointed to the abolition of mutual aid societies, if not before the socialist seizure of power, then as soon as programs of collectivization were set in motion. The abolition of village communes would reduce millions of rural workers to absolute misery and destroy their institutions to boot. A resurgent spirit of domination would suppress the psychology of mutual aid. Revolution on the Marxist models was not the same as social revolution organized “from the bottom up.”

The theory of mutual aid is sometimes represented as an overly optimistic depiction of human capability. At worst, the accusation is that Kropotkin presented an account of human goodness that reality explodes. Mutual aid is not a thesis about human nature. It is a theory about the capacity of humans to shape their environments and be molded by them. Kropotkin lived to see his worst fears about socialism realized.

But not even that setback has smothered the capacity for mutual aid or the willingness of local associations actively to embrace it. Mutual aid is most visible in times of crisis when states are unable or unwilling to act. Kropotkin’s call was to institutionalize those efforts and follow the intuitive appeal of the idea: co-operation is not about mutual benefit or mutual assurance or mutual destruction. It is about offering help when people need it, without requiring anything in return.

Peter Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid: An Illuminated Factor of Evolution, with an introduction by David Graeber & Andrej Grubacic, foreword by Ruth Kinna, preface by GATS and afterword by Allan Antliff is coming out this May from PM Press.

Use the coupon code “ROAR” to claim 25% discount on your pre-order.

Ruth Kinna is a member of the Anarchism Research Group at Loughborough University, UK. She is author of Kropotkin: Reviewing the Classical Anarchist Tradition (2016) and The Government of No One (2019).

Revolutionary change was the natural counterpart to Kropotkin’s evolutionary social theory. Kropotkin’s proposals, outlined in The Conquest of Bread and Fields, Factories and Workshops, were to descale and federate. He imagined the commune as the basic social unit with a new political economy of needs based on the abolition of labor divisions, wage systems and international trade supported by the integration of agriculture and industry in localities. Mutual aid was the means and the object of this transformation. Anarchist communism was a model for “consensus” which required co-operation to bring it into being.

In the last two chapters of Mutual Aid, Kropotkin highlighted examples of co-operative practice to demonstrate that the capacity for change endured even in the harshest, most repressive environments. Some of these demonstrate the pervasiveness of the “psychology” of mutual aid, the irresistible feeling “nurtured by thousands of years of human social life and hundreds of thousands of years of pre-human life in societies”. Typically, it is expressed through acts of solidarity and sacrifice. For Kropotkin, it explained the motivations of volunteers in the British Lifeboat Association, who risked their lives at sea to save others from drowning. The same psychology drove Welsh miners to enter collapsed mine shafts for the sake of fellow-worker buried under tons of coal.

Other examples of co-operative practice, by far the majority, point to the importance of the organizational aspects of co-operation. Having described the dismal collapse of the city-states and its disastrous consequences, Kropotkin argued that there were significant holes in the state’s armor. The state exercised an increasingly tight grip on corporations, co-operative societies and associations that once flourished independently of it, but this was far from complete. Even in Europe, Kropotkin was pleased to discover that village community continued to exist. Europe was “covered with living survivals … and European country life is permeated with customs and habits dating from the community period”.

Mutual aid “customs and habits” animated he “inner life” of Turkish villages and, likewise, “in the Arab djemmâa and the Afgan purra, in the villages of Persia, India, and Java, in the undivided family of the Chinese, in the encampments of the semi-nomads of Central Asia and the nomads of the far North”. In colonized Africa, too, “notwithstanding all tyranny, oppression, robberies and raids, tribal wars, glutton kings, deceiving witches and priests, slave-hunters, and the like” the “nucleus of mutual-aid institutions, habits and customs, growing up in the tribe and the village community, remains.” Colonized peoples did not require preparation for self-government. They did not need the chiefs who had been empowered by colonizers to rule them or the rising class of local educated elites who sought to oust both to implement direct rule.

Kropotkin was similarly enthused by the new forms of co-operation and mutual aid vested in a plethora of cultural associations and, especially, socialist organizations and actions: syndicates, trade unions, strikes, political movements, newspapers. Some of these were outgrowths of traditional guilds or, in Russia artisan artéls and others were entirely modern manifestations of co-operation and solidarity, created to resist domination and exploitation.

Revolution entailed protecting, nurturing and extending these multifarious mutual aid organizations to facilitate the habitual expression of the psychology. As a global exercise, the project inescapably heightened diversity. In this respect, Kropotkin was neither a traditionalist nor a modernist. The co-operative associations contained within the naturalistic, self-regulating, ethical anarchy he conceptualized were complex, distinctive and adapted to their local environments. The practice of mutual aid bound them together, promising, too, to transform the “European” aspiration for international solidarity into a reality. Kropotkin’s message was that the only route to revolutionary change was the extension of the principle of self-government, not the spread of ideology or adherence to party program.

In Mutual Aid Kropotkin used his “anarchized” evolutionary theory to attack advocates of state order or “subordination.” While this included laissez-faire liberals and conservatives of all stripes, he promoted his concept of revolution to highlight the shortcomings of currents within socialist and anarchist movements. In the 1870s Michael Bakunin had identified republicans and Marxists as advocates of political theology, as antagonistic to anarchy as any absolutist or cleric. Kropotkin followed suit but identified Nietzscheans and Marxists and the leading advocates of competition and “subordination” liable to derail the socialist cause from within.

The problem with Nietzscheanism turned principally on the promotion of the concept of autonomy at odds with the psychology of mutual aid, though it also had an organizational aspect. For Kropotkin, Nietzscheans were individualists who followed bourgeois norms rather than anarchist principles of co-operation. Not only did they fail to understand the organizational dimensions of social transformation, they undermined the cohesion of the workers’ associations. In doing so, they destroyed grassroots initiatives to consider economic, political and moral questions “precursory” to revolutionary transformation, Kropotkin argued in his 1889 lecture “Socialism: Its Modern Tendencies.”

Writing to Alexander Berkman in 1908, he remarked, “[i]t is the Masses which make the Revolutions – not the Individuals”. Observing that European workers’ had “abandoned” groups after they had been “invaded by all sorts of middle class tramps,” he added, “even the really revolutionary minded individuals, if they remain isolated, turn towards this Individualist Anarchism of the bourgeois which is nothing but the epicurean let it go of the Economists, spiced with a few ‘terrific’ phrases of Nihilism.” This was “food to frighten the Philistines” and best left to “the Nietzsche’ists … Bernard Shaw’ists, and all the similar arch-Philistine‘ists’.”

If the Nietzscheans’ lofty dismissal of organization endangered the spread of mutual aid, the imposition of a singular model was at least as dangerous to the prospects of co-operation. This was the threat that Kropotkin believed came from Marxism. Writing only a year after the publication of the book, Kropotkin explained to Guillaume that the significance of the Mutual Aid was twofold: it challenged the faulty premises of the Social Darwinist thesis of competition and it demonstrated the tyrannous implications of the Marxist theory of history. The priority Marx attached to the development of productive forces as the prerequisite for socialist transformation implied the extension of the competitive model, not its abolition. Kropotkin told Guillaume, “their metaphysics is authoritarian.”

However elaborately Marxists conceptualized the state, their theory of socialist transformation was predicated on the destruction of traditional communal and co-operative associations. Russia was uppermost in Kropotkin’s mind when he wrote to Guillaume, but the implications of his analysis were more far-reaching. Marxism pointed to the abolition of mutual aid societies, if not before the socialist seizure of power, then as soon as programs of collectivization were set in motion. The abolition of village communes would reduce millions of rural workers to absolute misery and destroy their institutions to boot. A resurgent spirit of domination would suppress the psychology of mutual aid. Revolution on the Marxist models was not the same as social revolution organized “from the bottom up.”

The theory of mutual aid is sometimes represented as an overly optimistic depiction of human capability. At worst, the accusation is that Kropotkin presented an account of human goodness that reality explodes. Mutual aid is not a thesis about human nature. It is a theory about the capacity of humans to shape their environments and be molded by them. Kropotkin lived to see his worst fears about socialism realized.

But not even that setback has smothered the capacity for mutual aid or the willingness of local associations actively to embrace it. Mutual aid is most visible in times of crisis when states are unable or unwilling to act. Kropotkin’s call was to institutionalize those efforts and follow the intuitive appeal of the idea: co-operation is not about mutual benefit or mutual assurance or mutual destruction. It is about offering help when people need it, without requiring anything in return.

Peter Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid: An Illuminated Factor of Evolution, with an introduction by David Graeber & Andrej Grubacic, foreword by Ruth Kinna, preface by GATS and afterword by Allan Antliff is coming out this May from PM Press.

Use the coupon code “ROAR” to claim 25% discount on your pre-order.

Ruth Kinna is a member of the Anarchism Research Group at Loughborough University, UK. She is author of Kropotkin: Reviewing the Classical Anarchist Tradition (2016) and The Government of No One (2019).