You know that urban myth about gators in the New York City sewer system....well it ain't New York and it ain't in a sewer and it's a croc not a gator.

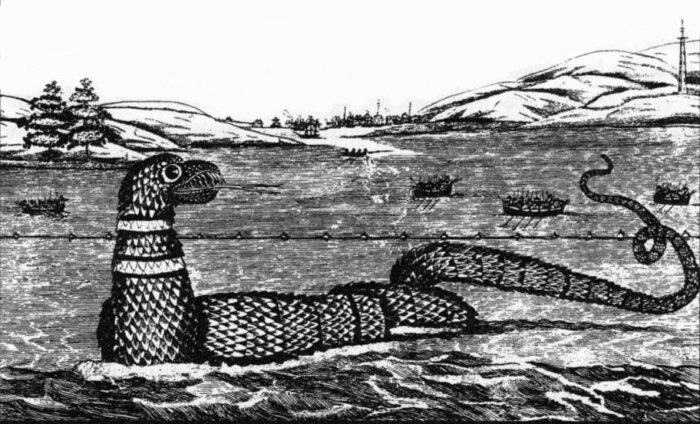

A small crocodile called Godzik, or Little Godzilla, which escaped from its cage in southern Ukraine at the end of May, is still at large and apparently enjoying itself, an official said Friday.In the old days this kind of thing would give rise to the myth of dragons, sea monsters and die vurm.The 70-centimetre (two-foot, four-inch) long Nile crocodile, which swam away during a publicity show on a beach on the Sea of Azov, is defying attempts to recapture it.

Dariel Adjiba, of the local office of the emergencies ministry, said the reptile had apparently made its home on an abandoned barge which ran aground in the shallow sea, where it could often be seen sunning itself.

AFP Photo: Close up of a nile crocodile in captivity. A small Nile crocodile called Godzik, or...Godzik had been with a travelling circus for about a year when it escaped at Maryupol on the northern shore of the inland sea.

SEE:

Strange Sea Creatures

I Thought I Saw A Putty Cat

Congo's Ghosts

The Fountain Of Youth

Turning Off The Nile

I Don't Do Mornings

Nessie was an Elephant?

Find blog posts, photos, events and more off-site about:

Monsters, Lake monsters, Loch Ness, Ness, Nessie, sea serpent, Scotland, myths, legends,cryptozoology,

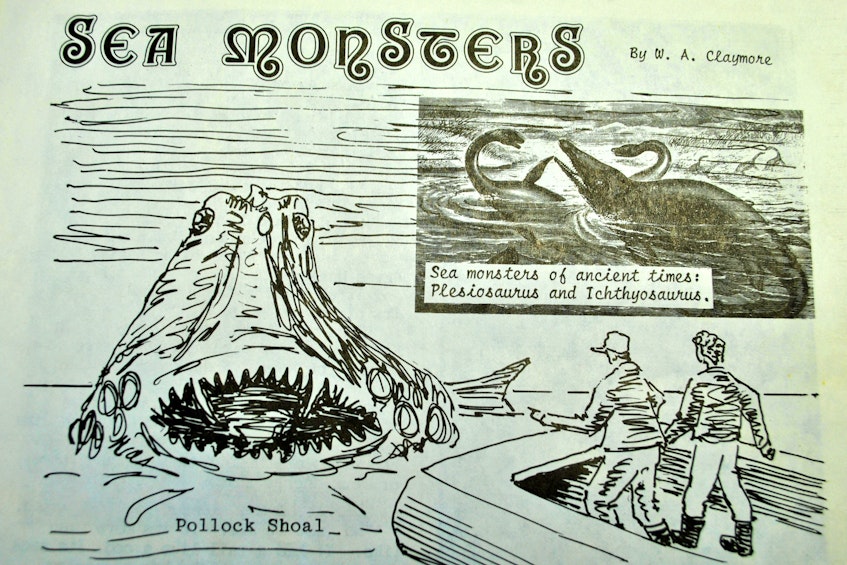

frilled, shark, dinosaur, fossil fish, living dinosaur, prehistoric shark, Japan, video, rare, animals, biology, marine biology, fish, living fossil

fish, animals, biology, science, Ukraine, croc, crocodilet, python, ophites, ophidian, gnostics, serpent worship, India, Christianity, Abrahamic, Judeaism, Islam, totems, primitive peoples, religion, rituals, magick, rites, cave paintings,archeology, archeologist, San, 70,000yearsago,

San people, South Africa, Kalahari, Sheila Coulson, Norway, University of Oslo, python, ophites, ophidian, gnostics, serpent worship, totems, primitive peoples, religion, rituals, magick, rites, cave paintings,archaeology, archaeologist, H.P. Lovecraft, lambton worm, Lair of the White Worm, Bram Stoker, Ken Russell, Die Vermis Mysteries, serpent, worm, myths, legends,cryptozoology,

frilled, shark, dinosaur, fossil fish, living dinosaur, prehistoric shark, Japan, video, rare, animals, biology, marine biology, fish, living fossil

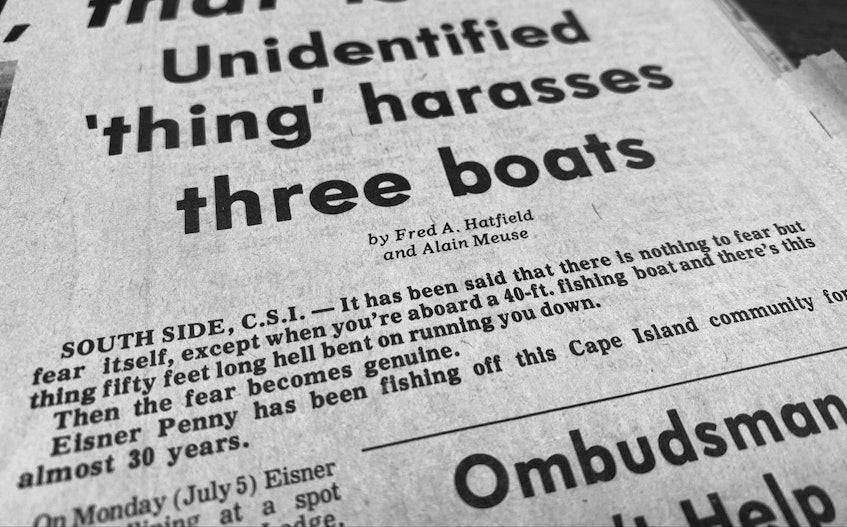

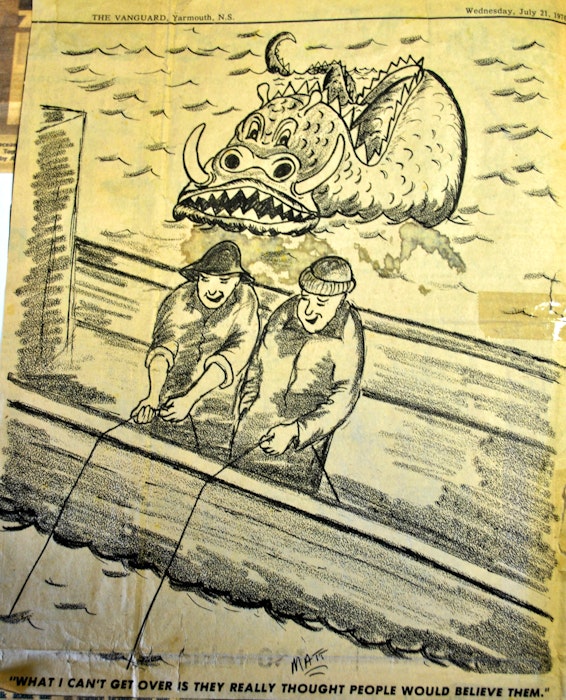

The first photo allegedly showing the existence of the Loch Ness monster was taken in 1934 by R. K. Wilson, a respected surgeon, and published in the Daily Mail.

The first photo allegedly showing the existence of the Loch Ness monster was taken in 1934 by R. K. Wilson, a respected surgeon, and published in the Daily Mail.