LIFE AFTER WARMING MAY 10, 2019

Jared Diamond: There’s a 49 Percent Chance the World As We Know It Will End by 2050

By David Wallace-Wells

Jared Diamond. Photo: Antonio Olmos/Observer/eyevine/Redux

Jared Diamond’s new book,

Upheaval, addresses itself to a world very obviously in crisis, and tries to lift some lessons for what do about it from the distant past. In that way, it’s not so different from all the other books that have made the UCLA geographer a sort of don of “big think” history and a perennial favorite of people like Steven Pinker and Bill Gates.

Diamond’s life as a public intellectual began with his 1991 book

The Third Chimpanzee, a work of evolutionary psychology, but really took off with

Guns, Germs, and Steel, published in 1997, which offered a three-word explanation for the rise of the West to the status of global empire in the modern era — and, even published right at the “end of history,” got no little flak from critics who saw in it both geographic determinism and what they might today call a whiff of Western supremacy. In 2005, he published

Collapse, a series of case studies about what made ancient civilizations fall into disarray in the face of environmental challenges — a doorstopper that has become a kind of touchstone work for understanding the crisis of climate change today. In

The World Until Yesterday, published in 2012, he asked what we can learn from traditional societies; and in his new book, he asks what we can learn from ones more like our own that have faced upheaval but nevertheless endured.

I obviously want to talk about your new book, but I thought it might be useful to start by asking you how you saw it in the context of your life’s work.Sure. Here’s my answer, and I think you’ll find it banal and more disappointing than what you might have hoped for. People often ask me what’s the relation between your books and the answer is there is none. Really, each book is what I was most interested in and felt most at hand when I finished my previous book.

Well, it may be a narrative that suggests itself to me because I’m thinking of Guns, Germs and Steel, Collapse, and this new one, Upheaval, but for me it’s interesting to note that each of them arrived when they did in a particular cultural, intellectual moment. That begins with Guns, Germs and Steel — it’s obviously a quite nuanced historical survey, but it was also read coming out when it did, as a kind of explanation for Western dominance of the planet …I would say you’re giving me more credit than I deserve. But one-third of the credit that you give me I do deserve. And that’s for Collapse. Guns, Germs and Steel, I don’t see it as triumphalist at all.

No, I don’t either. I don’t mean to say that. But it met the moment of Western triumphalism in our culture, I think.

The fact is that you and I are speaking English. We’re not speaking Algonquin and there are reasons for that. I don’t see that as a triumph of the English language. I see it as the fact of how history turned out, and that’s what Guns, Germs and Steel is about.

If you don’t mind dwelling on Collapse for a second … Has your view of these issues changed at all over the intervening years? I mean, when you think about how societies have faced environmental challenges, how adaptable they are and how resilient they might be, do you find yourself having the same views that you had a decade and a half ago?

Yes. My views are the same because I think the story that I saw in 2005, it’s still true today. It still is the case that there are many past societies that destroyed themselves by environmental damage. Since I wrote the book, more cases have come out. There have been studies of the environmental collapse of Cahokia, outside St. Louis. Cahokia was the most populous Native American society in North America. And I when I wrote Collapse it wasn’t known why Cahokia had collapsed, but subsequently we’ve learned that there was a very good study about the role of climate changes and flooding on the Mississippi River in ruining Cahokia. So that book, yes, it was related to what was going on. But the story today, nothing has changed. Past societies have destroyed themselves. In the past 14 years it has not been undone that past societies destroyed themselves.

Today, the risk that we’re facing is not of societies collapsing one by one, but because of globalization, the risk we are facing is of the collapse of the whole world.

How likely do you think that is? That the whole network of civilization would collapse?I would estimate the chances are about 49 percent that the world as we know it will collapse by about 2050. I’ll be dead by then but

my kids will be, what? Sixty-three years old in 2050. So this is a subject of much practical interest to me. At the rate we’re going now, resources that are essential for complex societies are being managed unsustainably. Fisheries around the world, most fisheries are being managed unsustainably, and they’re getting depleted. Farms around the world, most farms are being managed unsustainably. Soil, topsoil around the world. Fresh water around the world is being managed unsustainably. With all these things, at the rate we’re going now, we can carry on with our present unsustainable use for a few decades, and by around 2050 we won’t be able to continue it any longer. Which means that by 2050 either we’ve figured out a sustainable course, or it’ll be too late.

So let’s talk about that sustainable course. What are the lessons in the new book that might help us adjust our course in that way? As far as national crises are concerned, the first step is acknowledge — the country has to acknowledge that it’s in a crisis. If the country denies that it’s in a crisis, of course if you deny you’re in a crisis, you’re not going to solve the crisis, number one. In the United States today, lots of Americans don’t acknowledge that we’re in a crisis.

Number two, once you acknowledge that you’re in a crisis, you have to acknowledge that there’s something you can do about it. You have responsibility. If instead you say that the crisis is the fault of somebody else, then you’re not going to make any progress towards solving it. An example today are those, including our political leaders, who say that the problems of the United States are not caused by the United States, but they’re caused by China and Canada and Mexico. But if we say that our problems are caused by other countries, that implies that it’s not up to us to solve our problems. We’re not causing them. So, that’s an obvious second step.

On climate in particular, there seem to be a lot of countervailing impulses on the environmental left — from those who believe the only solution to addressing climate is through individual action to those who are really focused on the villainy of particular corporate interests, the bad behavior of the Republican Party, et cetera. In that context, what does it mean to accept responsibility?

My understanding is that, in contrast to five years ago, the majority of American citizens and voters recognize the reality of climate change. So there is, I’d say, recognition by the American public as a whole that there is quite a change in that we are responsible for it.

Right.

As for what we can do about it, whether to deal with it by individual action, or at a middle scale by corporate action, or at a top scale by government action — all three of those. Individually we can do things. We can buy different sorts of cars. We can do less driving. We can vote for public transport. That’s one thing. There are also corporate interests because I’m on the board of directors for the World Wildlife Fund and I was on the board of Conservation International, and on our boards are leaders of really big companies like Walmart and Coca-Cola are their heads, their CEOs, have been on our boards.

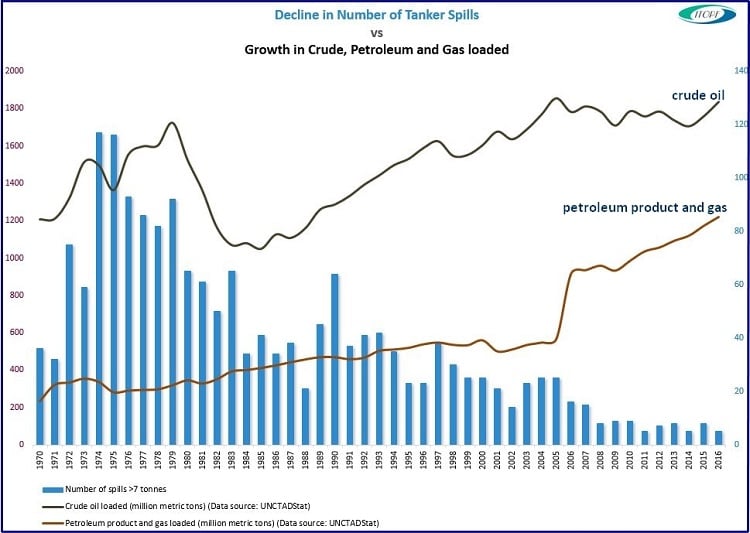

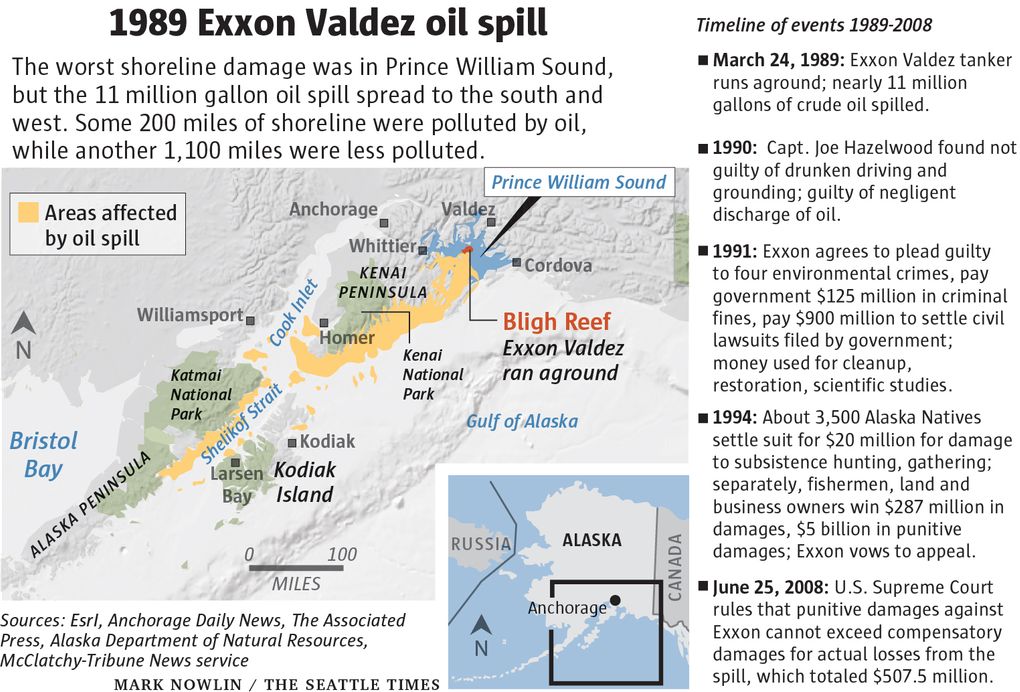

I see that corporations, big corporations, while some of them do horrible things, some of them also are doing wonderful things which don’t make the front page. When there was the Exxon Valdez spill off Alaska, you can bet that made the front page. When Chevron was managing its oil field in Papua New Guinea in a utterly rigorous way, better than any national park I’ve ever been in, that certainly did not make the front page because it wasn’t a good picture.

And then finally the Republican Party, yes. Government has a role. In short, climate change can be addressed at all these levels. Individual, corporation, and the national level.

In the book, when you write about the present day — you talk about climate, you talk about resources, but you also talk about the threat of nuclear war and nuclear weapons. It may be kind of a foolish question to ask, but … how do you rank those threats? I’m repressing a chuckle because I know how people react when I answer that. Whenever somebody tells me, “How should we prioritize our efforts?” My answer is, “We should not be prioritizing our efforts.” It’s like someone asking me, “Jared, I’m about to get married. What is the most important factor for a happy marriage?” And my response is, “If you’re asking me what is the most important factor for a happy marriage, I’d predict that you’re going to get divorced within a few years.” Because in order to have a happy marriage you’ve got to get 37 things right. And if you get 36 right but you don’t get sex right, or you don’t get money right, or you don’t get your in-laws right, you will get divorced. You got to get lots of things right.

So for the state of the world today, how do we prioritize what’s going on in the world? We have to avoid a nuclear holocaust. If we have a nuclear holocaust, we’re finished, even if we solve climate change. We have to solve climate change because if we don’t solve climate change but we deal with a nuclear holocaust, we’re finished. If we solve climate change and don’t have a nuclear holocaust but we continue with unsustainable resource use, we’re finished. And if we deal with the nuclear problem and climate change and sustainable use, but we maintain or increase inequality around the world, we’re finished. So, we can’t prioritize. Just as a couple in a marriage have to agree about sex and children and in-laws and money and religion and politics. We got to solve all four of those problems.

What should we do? Are there lessons from history?

To conduct a happy marriage, it’s not enough to sit back and have a whole listed view of a happy marriage. Instead you need to discuss your budget and your in-laws and 36 other things. As far as the world is concerned, solving national crises, the checklist that I came up with in my book is a checklist of a dozen factors. Now, I could make a longer checklist, or I could make a shorter checklist, but if we have a checklist of three factors it would be obvious we’re missing some big things. And if we had a checklist of 72 factors, then nobody would pick up my book and they wouldn’t pay attention to it.

As an example of one of those factors that the United States is really messing up now, it’s the factor of using other countries as models for solving problems. Just as with personal crises, when someone’s marriage breaks down or is at risk of breaking down, one way of dealing with it is to look at other people who have happy marriages and learn from their model of how to conduct a happy marriage. But the United States today believes what’s called American exceptionalism. That phrase, American exceptionalism means the belief that the United States is unique, exceptional, therefore there’s nothing we can learn from other countries. But we’ve got this neighbor, Canada, which is a democracy sharing our continent and there are other democracies throughout Western Europe in Australia and Japan. All of these democracies face problems that we are not doing well with. All of these democracies have problems with their national health system. And they have problems with education. And they have problems with prisons. And they have problems with balancing individual interests with community interests. But the United States, we too have prisons and we’ve got education and we have a national health system, and we are dissatisfied. Most Americans are dissatisfied with our national health system, and most Americans are increasingly dissatisfied with our educational system.

Other countries face these same problems and other countries do reasonably well, better than the United States in solving these problems. So, one thing that we can learn is to look at other countries as models and disabuse ourselves of the idea that the United States is exceptional and so there’s nothing we can learn from any other country, which is nonsense.

Do you think of this as being a sort of book about the path forward for the U.S.? Or do you think of it as having a broader, global audience?

It is a book about the U.S. plus 215 other countries. The United States is one country in the world, and we’ve got our own problems, which we are struggling with. I came back from Italy and Britain. Britain when I was there was at the peak of Brexit, but Britain is still at the peak of Brexit.

They’re not leaving that behind.

They’re making, I would say, zero progress with Brexit. Italy has its own big problems. Papua New Guinea has its own problems. I’m trying to think what country does not have problems …

It’s hard.

Norway is doing pretty well. What else?

Portugal maybe is doing relatively well.

Which one is that?

Portugal, maybe.

Portugal, maybe. Costa Rica, all things considered. Well, Costa Rica has problems because I think all four of Costa Rica’s last four presidents are in jail at the moment. That’s a significant problem.

If there’s hardly a nation in the world that seems to be a good model, a thriving example for other nations of the world to follow behind, how much faith does that give you that we can find our way to a kind of sustainable, prosperous, and fulfilling future?

That’s an interesting question. If I had stopped the book on the chapter about the world without writing the last six pages, it would have been a pessimistic chapter, because at that point I thought the world does not have a track record of solving difficult problems. The U.N., well bless it, but the U.N. isn’t sufficiently powerful, and therefore I feel pessimistic about our chances of solving big world problems.

But then, fortunately, I learned by talking with friends that the world does have a successful track record in the last 40 years about solving really complex, thorny problems. For example, the coastal economics. So many countries have overlapping coastal economic zones. What a horrible challenge that was to get all the countries in the world to agree with delineating their coastal economic zones. But it worked. They’re delineated.

Or smallpox. To eliminate smallpox it had to be eliminated in every country. That included eliminating it in Ethiopia and Somalia. Boy, was it difficult to eliminate smallpox in Somalia, but it was eliminated.

I wonder if I could ask you about California in particular. It’s interesting to me in the sense that when I look at the example of California,

I see a lot of reasons for hope in the sense that there’s quite focused attention on climate and resources used there — probably more sustained interested in those subjects than there really is anywhere else in the U.S. And it has policy that’s, by any metric, I think more progressive than the relevant policies elsewhere in the U.S.

And yet, it’s also a state that — maybe it’s an unfortunate phrase — by accident of geography is also facing some of the most intense pressures and dealing with the most intense impacts already, from water issues to wildfire and all the rest of it. As a Californian who’s informed by these concerns looking at the future and thinking about the future, how does the future of California look to you?

California has problems like every other place in the world. But California makes me optimistic. It does have the environmental problems but nevertheless we have, I would say, one of the best state governments, if not the best state government in the United States. And relatively educated citizens. And we have the best system of public education, of public higher education in the United States. Although, I, at the University of California, know very well that we are screaming at the legislature for more money. So we have problems but we’re giving me hope at how we’re dealing with those problems.

I’m a native New Yorker and lived my whole life in this environment on the East Coast. And when I see images of

those wildfires and when I hear stories of people I know or people I meet, and the fact that they’ve evacuated, the fact that no matter where you are in Southern California, also in parts of Central California and Northern California, you have an evacuation plan in mind. I just don’t understand how you guys can live like that. It must begin to impose some kind of psychic cost.

Well, I understand psychic costs and I understand getting my head around it because I was born and grew up in Boston. The last straw for me was that in Boston I sang in the Handel and Haydn Society chorus, and we were going to perform in Boston Symphony Hall the last week in May and our concert was canceled by a snowstorm that closed Boston down. And for me that was the last straw. I do not want to live in a city where a concert in Symphony Hall is going to get closed down in the last week of May by a snowstorm.

That’s just one event, but the fact is that Boston is and was miserable for five months of the year in the winter and then it’s nice for two weeks in the spring and then it’s miserable for four months in the summer, then it’s nice for a few weeks in the fall. Similarly with New York. So when I moved here, my reaction is, “Yes, we have the fires and we have the earthquakes and we have the mudslide and we have the risk of flooding. But, thank God for all those things because they saved me from the psychic costs of living in the Northeast.”

\