It’s been 30 years since the Exxon Valdez oil spill.

Here’s what we’re still learning from that environmental debacle.

1 of 11 | To try to ease the toll on the Prince William Sound, hundreds of workers spread

1 of 11 | To try to ease the toll on the Prince William Sound, hundreds of workers spread

out along the shores of Green Island after the... (Harley Soltes / The Seattle Times) More

By Hal Bernton and Lynda V. Mapes

Seattle Times staff reporters

March 24, 2019 at 6:00 am Updated March 25, 2019 at 9:09 am

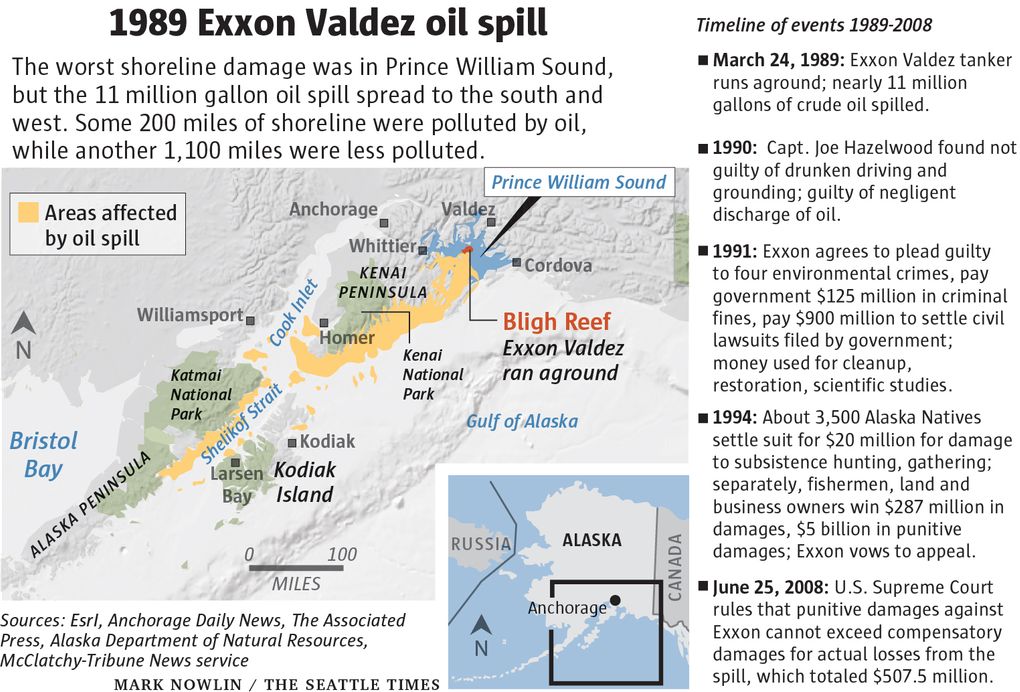

Before dawn on March 24, 1989, Dan Lawn stepped off of a small boat and onto the boarding ladder dangling from the side of the grounded Exxon Valdez oil tanker. As he made the crossover, he peered down into the water of Prince William Sound, and saw, in the glare of the lights, an ugly spectacle he would never forget.

“There was a 3-foot wave of oil boiling out from under the ship, recalls Lawn, who was then a Valdez-based Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation employee helping to watchdog the oil industry. “You couldn’t do anything to stop it.”

Lawn was one of the first responders to reach the 986-footlong Exxon Valdez after it went off course and punctured its hull on Bligh Reef in a debacle that marks its 30th anniversary Sunday.

Lawn spent a long day on board assessing the damage as oil gushed out. There would be no quick and coordinated spill response to slow the spread. Some 11 million gallons of crude would leak out of the Exxon Valdez in what was then the largest oil spill in U.S. history, and one that Lawn had long warned could happen.

The Exxon Baton Rouge, smaller ship, attempts to off-load crude

from the Exxon Valdez that ran aground in Prince William Sound,

Valdez, Alaska, spilling over 270,000... (Rob Stapleton / AP) More

Eventually, the oil would foul parts of 1,300 miles of coastline, killing marine life ranging from microscopic planktons to orcas in an accident that would change how the maritime oil-transportation industry does business in Alaska, and to a lesser extent, elsewhere in the world.

Today, due to changes to U.S. law and international regulations, all oil tankers traversing the oceans are double-hulled, unlike the more breech-prone single hull of the Exxon Valdez. This significantly reduces but does not eliminate the risk of spills, as was demonstrated last year when a double-hulled Iranian tanker exploded and leaked fuel oil after crashing into a freighter in the South China Sea.

In Washington state, the Legislature overhauled oil-spill laws in the years after the Exxon Valdez. The state is a regional refining hub, with more than 9.45 billion gallons of petroleum products traveling over water annually. The lawmakers’ actions enabled the state Department of Ecology to strengthen prevention and response efforts. All barges carrying oil — as well as oil tankers — must have double bottoms. Another requirement is for a rescue tug to be stationed at Neah Bay to respond to vessels in distress.

A loon oiled by the spill awaits transport to a bird-rescue center.

Carcasses of 395 loons of four species were collected during the spill,

and it is estimated that 720 to 2,160 loons died from the oil.

(Craig Fujii / The Seattle Times)

The volume of oil that tankers carry through Washington waters could increase dramatically in the years ahead. That’s because Canada is poised to approve a tripling of capacity in the TransMountain Pipeline so that bitumen processed from interior oil sands can be exported from British Columbia to global markets.The threat of massive spills does not only come from tankers. The 2010 Deepwater Horizon drilling rig explosion that killed 11 workers led to an oil spill of 168 million gallons — dwarfing the amount released by the Exxon Valdez.

“If there is a single lesson we have learned, it’s that we have to do everything possible to prevent all sorts of scenarios that could lead to a catastrophic spill,” said Rick Steiner, a marine conservationist who — at the time of the Exxon Valdez spill — was employed by the University of Alaska in the Prince William Sound community of Cordova.

Unheeded warnings

Before the Exxon Valdez, Steiner and Lawn were outspoken critics of the Alaska oil industry’s preparation for a potential spill by the tankers that ferried Alaska North Slope crude to refiners in Washington and elsewhere in the United States.

Steiner networked with Prince William Sound fishermen who believed the oil industry had reneged on safety measures, and a disaster was all but inevitable. He pushed, unsuccessfully, for the creation of a citizen oversight council to prod the oil industry to ramp up safety measures. It was founded after the spill.

Meanwhile, Lawn sounded the alarm within the ranks of the state Department of Environmental Conservation. He said the equipment outlined in a response plan by Alyeska Pipeline Service Company, an oil-industry consortium, was not readily available. Even if it could be accessed, it would fall far short of what was needed.

“The managers were told that, but they didn’t want to hear it,’ said Lawn, who is now retired and divides his time between Kirkland, Washington, and Valdez, a Prince William Sound town where tankers load up with oil that arrives through the trans-Alaska pipeline.

When the accident happened, there was far too little response equipment, and some of it was buried in snow.

In this April 13, 1989 photo, Edward Jones of Valdez wipes off rocks

on the shoreline of Cabin Bay on Naked island in Prince William Sound.

Thirty years later, oil can still be found on some...

(Bob Hallinen / McClatchy Newspapers) More

For three days, relatively calm weather prevailed. The oil lay thick around the vessel, offering a crucial window of time for action. Then came a storm that scattered the oil, splattering coastlines to the west and south. For four years, crews embarked on a $2.1 billion cleanup that left behind crude that still can be detected on some stretches of the Prince William Sound shoreline.

Up to 10,000 workers were employed in the cleanup, and 1,000 boats. One line of an attack was using hot water on the beaches, but that was stopped when it was found to cook marine life, do more harm than good, according to research cited by the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council.

Amid the oil slicks in the water, killer whales surfaced to breathe. Among a resident pod of 36 whales in the area, 14 had disappeared by 1990, according to the Trustee Council.

Whales likely inhaled petroleum vapors and may have eaten contaminated prey.

Fourteen whales in a resident killer whale pod disappeared between 1989 and 1990.

(John Gaps III / Associated Press)

Over the long term, a transient whale pod that also frequented Prince William Sound fared the worst. Before the spill, the pod had 22 whales. Since then, the pod has declined to seven whales, and there have been no new calves born

Craig Matkin, a researcher for the nonprofit Gulf Watch Alaska, has monitored the whales since 1984. He said the transient whales, which eat seals, were probably the most heavily affected by the spill because they not only breathed the fumes and oil, but also ate oiled prey.

That pod appears doomed. “I give them maybe a two percent chance (of survival). It is so sad,” Matkin said.

Changes made, concerns linger

Three decades after the spill, Alyeska and the oil companies — under pressure from the state of Alaska — have greatly expanded measures to prevent spills. Two escort tugs, for example, accompany every oil laden tanker that motors through Prince William Sound. If needed, they can steer the tanker, counter any unwanted move or take it under tow.

If oil should escape a tanker, Alyeska has more than 40 miles of boom, compared with five in 1989.

Alyeska has 140 skimmers, compared with 13 back then, and the newer models operate much more efficiently, capturing less water.

The capacity to store cleaned up oil with barges or other floating equipment is more than 50 times greater than at the time of the spill.

As memories of the Exxon Valdez fade, a plea to Congress to retain the lessons learned

By Liz Ruskin, Alaska Public MediaMay 8, 2019

Mako Haggerty of Homer sits on the Prince William Sound Regional

Citizens’ Advisory Council. (Photo by Liz Ruskin/Alaska Public Media)

One of the lessons of the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill is that the response has to begin immediately. Time is short if there’s any hope of limiting the damage.Audio Player

Congress seemed to have learned that lesson by 1990, when it imposed a per-barrel tax to pay for the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund. The fund allows the government to launch a spill response and pay compensation, even before the company at fault is held to account.

But at the end of last year, Congress allowed that law to expire.

Mako Haggerty of Homer was among a group of Alaskans in Washington, D.C. He recently to ask lawmakers to renew the law.

“Thirty years was a long time ago,” Haggerty said in an interview outside the U.S. Capitol, between meetings. “A lot of people are moving on, and we need to remember what happened.”

Haggerty is a member of the Prince William Sound Regional Citizens’ Advisory Council. He was a commercial fisherman when the Valdez ran aground, and he worked on the spill cleanup in the sound and the outer Kenai Peninsula.

Slick on the water following the Exxon Valdez oil spill on March 24, 1989. (Public domain photo courtesy Alaska Resources Library & Information Services)

“I think we’re still suffering some of the effects of the Exxon Valdez spill,” he said. “What we want to do is prevent spills. That’s the main thing.”

Haggerty likes a bill Sen. Dan Sullivan, R-Alaska, sponsored: the Spill Response and Prevention Surety Act. It would permanently restore the oil spill fund and keep the 9-cents-per-barrel tax. But Sullivan’s bill would cap the fund at $7 billion. Once the fund reaches that level, the tax would be suspended until the value drops below $5 billion.

Haggerty said the ceiling is important.

“The fund is there just to get the cleanup started as soon as possible. So we don’t need a huge amount of money,” he said. “And anytime you have a huge amount of money sitting around, people want to use it for other purposes.”

The bill would also provide $25 million in annual grants to states for spill prevention.

Haggerty said prevention is critical. That’s one of the hard lessons of the 1989 spill.

“You have herring and bidarkis and clams and a lot of the subsistence foods from Prince William Sound, around the villages, that are still not there,” he said.

Sen. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, is a co-sponsor of Sullivan’s bill, which has not yet advanced to a committee hearing.

Considering future impacts of oil and vessel distress in Alaska marine water

By Emilie Springer For the Homer News

Wednesday, March 20, 2019

Editor’s note: This article has been updated to correct the name of the Prince William Sound Regional Citizens Advisory Council.

Three decades ago on March 24, 1989 the oil tanker Exxon Valdez struck Bligh Reef at the entrance of Valdez Arm in Prince William Sound, spilling 10.8 million gallons of crude oil in critical need of immediate response. On Feb. 20, 2019 Alaska Sea Grant hosted a workshop at the Dena’ina Center in Anchorage to revisit various dimensions of how damages of the spill were addressed through a focus on three categories relevant to community and human impacts of the environmental disaster relative to oil spills: public health, social disruption and economic loss.

Presenters and panelists incorporated a broad range of research establishments as well as state and federal organizations, including Sea Grant affiliates from both Alaska and Texas, the Prince William Sound Regional Citizens Advisory Council, United States Coast Guard, the Prince William Sound Science Center, UAA’s Institute for Social and Economic Research, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, National Institute of Health, Alaska Ocean Observing System and the Alaska Chaddux Corporation. Most notable about this assortment is that presentations offered feedback and findings to a diverse audience — it was not solely research-structured but included more interactive response venues through local levels in both mid-size communities in the Gulf of Alaska and smaller rural villages in the northwestern coastal and island regions of Alaska. After each presentation, audience members were welcome to express themselves or ask questions.

One notable set of comments came from an elder audience member who grew up on Little Diomede Island located in the center of the Bering Strait and currently living in Wales, Alaska. The individual provided commentary in a casual conversational manner related to a general topic of change and transition over time. He talked about changes he has experienced in transportation from dog sleds to snow machines and how those dimensions influenced the need and opportunities for local collection of dog food. He also talked about transitions related to the role of how ivory collections were utilized in the community and the shift away from a once common resource has created major transitions in community identity. His concluding commentary seemed to imply that “modifications are constant, and we need to accept that changes will happen for various reasons.” This was not necessarily a positive validation of the human-caused dimension of a major oil spill, but that adaptation is inevitable.

Economist Gunnar Knapp, retired from the UAA Institute for Social and Economic Research, provided discussion comments that strongly encouraged a necessity for continually collecting base-line data and clear obligations for advance contingency plans and strategies prior to potential future disaster events. A difficulty of this dimension is acquiring funding to continually update information without required administrative obligations. Established protocols may help with response effectiveness because efforts to gather data on what is impacted once habitat suffers destruction is ineffective. Dealing with this is a political challenge. As Knapp points out, “budget cuts inevitably come from both the state and federal government. Prevention is perceived as burdensome on industry, so prevention is not the focus.”

“Declines in funding decrease response availability and funding is a perpetual challenge,” collected conference notes suggest.However, as speaker Richard Kwok with the National Institute of Health pointed out in his presentation, “it is critical to consider features of preparedness and response because we need to expect disaster; at some point they are unavoidable and inevitable.”

“Each disaster will present new issues and uncertainties,” he also said.

Concurrently, he discussed some of the challenges of disaster examination.

“There is no formal way to activate and coordinate research. Funding is difficult to find, official IRB protocols are challenging to follow, ethical issues are difficult to address, there is a lack of trained researchers to collect data and inclusion of community stakeholders is difficult,” he said.

That particular list of challenges is a demonstration of the contrast between endorsed, official research with more generalized interaction with impacted stakeholders. Kwok shared a useful website from the National Institute of Health related to disaster response protocols, data collection and training: https://dr2.nlm.nih.gov.

Another dimension of panel discussion that Knapp contributed to was discussion of the diverse communities and regions of western Alaska. As he noted, “what works well in one location may not in another.” Activity, availability and skills vary substantially between communities.

Another feature in Sea Grant’s collected conference notes relative to Alaska’s most rural communities suggest “prevention strategies need to be tailored to changing times. There are complex environmental issues impacting each community and the difficulty of keeping up with and monitoring all of them depends on location.” To address this requires regional communication networks and an awareness of “gatekeepers” in villages and among tribal leaders to relay information in a dependable manner.

As a speaker in one panel mentioned, “Folks in northern regions need to focus 100 percent on prevention. Though the people in those communities are resourceful, there are deficiencies to response availability.” Deficiencies, in this case, relates to what is accessible to communities in in the event of a spill disaster.

Presenter James Nunez with the US Coast Guard discussed some community reaction difficulties related to “colossal documentation” or lengthy publications.

“In these types of papers, verbosity is often too formalized and meaning can get lost in the density of composition,” Nunez explained. “There can be a real benefit to informality when trying to address the unofficial knowledge and awareness of individuals who make up a community.”

Attention to local knowledge and how to further disperse awareness and preparedness provides an opportunistic role for public journalism as an outreach tool.

“It behooves us to engage with community members to learn the most about all the nooks and crannies of identity and potential impacts. It is important to tap into and incorporate local information that can help us understand how impacts will be felt,” Nunez said.

Throughout the event, topics that emerged repetitively among speakers were community engagement and venues for integrating personal experiences and voice for better general communication across user groups and between user groups and agencies responsible for reaction to a spill event. It is important to integrate a certain degree of formality and professionalism while also capturing a spectrum of personal experiences and observations and attending to them in a proficient manner.

Sustainability of human and natural communities are reciprocal: they depend on each other and a variety of expressions. To capture the assorted influences, a diversity of voices is critical. This gathering fittingly shared that scope.

Exxon Valdez: what lessons have we learned from the 1989 oil spill disaster?

25 years since the oil tanker spilled millions of gallons of crude oil in the Gulf of Alaska, we remain callously unprepared to mitigate a future oil spill in the Arctic waters

Martin Robards

Wed 14 Feb 2018 18.15 GMT

Staining the vista of the Chugach Mountains, the Exxon Valdez lies atop Bligh Reef two days after the grounding on 25 March 1989. Photograph: Natalie B Fobes/NG/Getty Images

It’s been 25 years to the day since human error allowed the Exxon Valdez tanker to run aground in the pristine waters of Prince William Sound in the Gulf of Alaska, dumping 11 million gallons of crude oil in what would become the greatest environmental disaster for an entire generation.

Even after the recent Deepwater Horizon incident in the Gulf of Mexico — a much larger accident in terms of the amount of oil released — the spectre of Exxon Valdez remains fresh in the minds of many Americans old enough to remember the wall-to-wall media coverage of crude-smothered rocks, birds, and marine mammals.

In the quarter century since the Exxon Valdez foundered, changing economic and climatic conditions have led to increased Arctic shipping, including increasing volumes of petroleum products through the Arctic. Sadly, apart from a few areas around oil fields, there is little to no capacity to respond to an accident – leaving the region’s coastal indigenous communities and iconic wildlife at risk of a catastrophe.

Local Alaskans and conservationists like myself – who witnessed the Exxon Valdez impact at close range – will never forget the damage. The wake of oil spread far from Bligh Reef, devastating life in Prince William Sound, killing over a quarter of a million seabirds at the large colonies in neighbouring Cook Inlet, before moving along the coast of Kodiak and to a point on the Alaska Peninsula 460 miles to the south

Exxon Valdez oil spill workers and maxi-barge hose beach after Corexit test on Quayle beach, Smith lsland in Prince William Sound, Alaska, US, on 7 August 1989. Photograph: Alaska Resources Library and Information Services (Arlis)

Yet more than memories remain. Oil persists beneath the boulders and cobbles of the affected region, sea otters have only just recovered after 25 years, and some species such as Pacific herring and the fisheries reliant on them are still not recovering at all, despite Exxon’s overtly optimistic prediction of a quick and full recovery of Prince William Sound.

Advertisement

The fact is that even under ideal conditions, relatively little oil is actually recovered from a large spill. Its long-term impacts demand that we redouble our efforts on prevention to protect natural resources and the communities that rely on them – particularly in the Arctic where the environmental challenges are greater, the response and cleanup infrastructure frequently poor, and the logistics for mounting a response in remote environments immense. Furthermore, Arctic wildlife tends to aggregate in staggering numbers, rendering large portions of entire species vulnerable to a spill, like the seabirds of Cook Inlet.

Late last year, recognising that accidents will happen, I helped to lead a workshop with representatives of government agencies and coastal communities to address the lack of oil spill response capacity in the waterways separating Alaska in the United States from Chukotka in the Russian Federation. Residents from the Bering and Anadyr Straits and other villages met with representatives from federal and state agencies and other organisations in order to better identify the best ways to understand, prepare for, and respond to, an oil spill in a co-ordinated manner

While overall co-ordination of any large oil spill naturally rests with a formalised incident command, the first responders to a future oil spill in Arctic waters will more often than not be from the nearest local communities. Local hunters possess knowledge of natural resources passed down over centuries, including the migratory movements of birds, marine mammals, and fish, as well as how to operate safely in their coastal waters.

These are the people who stand to lose the most in the event of a spill, which could devastate regional wildlife and fish populations. Providing them the proper training, equipment, and infrastructure for their communities will help them to play a more meaningful role in planning for and safely responding to any future environmental disasters.

Communities, agencies, and other responsible groups on both sides of the political border must also establish predetermined roles and priorities. For example, will oil be allowed to wash ashore or will an attempt at dispersal be made? While oil on Arctic beaches is nobody’s wish, the long-term impacts of dispersant use on food security in the Arctic environment are unknown. Both options have long-term environmental and human health consequences – and only through local input into the planning process can these difficult decisions be addressed.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Valdez-based seafood processors picket Exxon's headquarters protesting a shortage of work due to the Exxon Valdez oil spill on 24 July 1989. Photograph: Arlis

During the Exxon Valdez incident, villages dependent on fishing were financially ruined. A similar event farther north, impacting the health and abundance of marine mammal populations, could be even more devastating. Such losses of iconic wildlife and damage to this stunning environment threaten not only a unique and precious part of our planet; but also the nutritional needs of coastal communities and a critical component of their cultures.

In the end, the story of the Exxon Valdez remains a cautionary tale. While simply hoping for the best may be the cheapest way forward given the resources required to establish functional networks of community and government bodies willing and able to work together, accidents do and will continue to happen. If we are to secure the long-term health and security of the Arctic’s magnificent natural resources and vibrant indigenous cultures there can be little doubt concerning the value of both prevention and preparedness.Guardian report on Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989

• Dr Martin Robards directs the Wildlife Conservation Society’s Arctic Beringia programme

Exxon Valdez: high winds threaten Alaskan oil slick - archive, 1989

27 March 1989: Threat grows from worst US spill as tanker flounders

Wed 27 Mar 2019

Containment booms surround the oil tanker Exxon Valdez after it ran aground in Prince William Sound, Alaska, March 1989. Photograph: ReutersHigh winds yesterday threatened to double the size of an oil slick menacing marine life in Alaskan waters as government investigators arrived on the Valdez to question the captain and crew members of the supertanker that precipitated the worst oil spill in US history.

State officials feared that high winds could aggravate the problem by doubling the size of the slick, estimated by Exxon to be about 12 square miles, while state officials contended it was 50 square miles.

Exxon Valdez oil spill – in pictures

Deteriorating conditions could also threaten the Valdez, still carrying more than a million barrels of crude, and listing severely at the mouth of Prince William Sound.

The Coast Guard has subpoenaed for questioning by National Transportation Safety Board officials the captain, Mr Joe Hazelwood, a 20-year Exxon ship veteran who was in his cabin and not on the bridge when his ship, the Exxon Valdez, struck the well-marked Bligh reef last Friday. Blood alcohol tests have already been administered to three crewmen, but the Coast Guard has yet to disclose the results.

The ship strayed 1.5 miles outside its approved shipping lane before crashing into the reef, spilling 11 million gallons of oil into Prince William Sound, considered one of the richest marine environments in North America. The sound features towering fiords, tree-lined coasts, and rock pinnacles jutting out of the water, and teems with sea lions, seals, killer whales, and sea birds.

Emilie Springer is a freelance writer living in Homer.

Although the president of Exxon, Mr WB Stevens, said the company was giving its full resources and providing additional equipment to clean up the spill, fishermen and Alaskan officials attacked Exxon for its tardiness.

‘The initial response was inadequate and didn’t match the planned, outlined response measures to be taken in a spill,’ complained Mr Dennis Kelso, the commissioner of the Alaskan Department of Environmental Conservation.

The first containment booms and oil removal equipment did not reach the scene until 10 hours after the incident, partly because a barge needed to transport them had been damaged in a storm two weeks ago. The equipment had to be transferred to another barge.

Other state officials ridiculed Exxon’s excuse that it had first to wait for the department to assess the problem.

Because Exxon and the Alaska Pipeline Service Company dragged their feet, the slick has become too large to deal with by only mechanical means - booms and pumps. Exxon will be using dispersants - liquid detergent made by the company - to break the oil before it reaches the shore in large quantities.

A plane dropped 200,000 dispersants on Saturday, but missed the oil slick because the pilot failed to distinguish it from the ‘black’ Alaskan waters. The darkness of the sea has in fact led to conflicting estimates of the size and location of the slick.Rescue crews were trying to pump the remaining oil from the supertanker into a sister vessel, the Baton Rouge, but so far only 800 gallons have been offloaded with the two pumps in use. Exxon says it is planning to bring in another six to eight pumps to speed up the operation.An Exxon senior enviornmentalist scientist, Dr Allen Mackey, said the extent of damage to marine life could not be assessed immediately, but added that the spawning herring at Bligh Island, next to the reef, would have to be written off. Also at risk were young salmon just entering the sound from local streams.

February 6, 2019/

As reported in the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, there are still lessons to be learned from the Exxon Valdez oil spill that occurred on March 24th, 1989.

A recent report issued by the United States Government Accountability Office (U.S. GAO) found that some organizations involved in environmental cleanup, restoration and research weren’t talking to each other during the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill or the Deepwater Horizon oil spill that occurred in 2010. In fact, some agencies weren’t even aware that the other existed.

The U.S. Congress, reacting to the Exxon Valdez spill, created the Interagency Coordinating Committee on Oil Pollution Research as part of the Oil Pollution Act of 1990. The committee’s purpose is to “coordinate oil pollution research among federal agencies and with relevant external entities,” according to the GAO. The committee, which has representatives from 15 agencies, is expected to coordinate with federal-state trustee councils created to manage restoration funds obtained through legal settlements.

GAO investigators found, however, that “the committee does not coordinate with the trustee councils and some were not aware that the interagency committee existed.”

Although three decades have passed since oil soiled the surface of Prince William Sound and rolled onto its shores, evidence of the spill remains. GAO staff visited the spill site in May of last year “and observed the excavation of three pits that revealed lingering oil roughly 6 inches below the surface of the beach …” Restoration is largely complete in Prince William Sound, but some work continues and research will continue for decades, the GAO report notes.

Background: Exxon Valdez Spill and Clean-up

As reported in History.com, The Exxon Valdez oil spill was a man-made disaster that occurred when Exxon Valdez, an oil tanker owned by the Exxon Shipping Company, spilled 41 million litres of crude oil into Alaska’s Prince William Sound on March 24, 1989. It was the worst oil spill in U.S. history until the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010. The Exxon Valdez oil slick covered 2,000 kilometres of coastline and killed hundreds of thousands of seabirds, otters, seals and whales.

Exxon payed about $2 billion in cleanup costs and $1.8 billion for habitat restoration and personal damages related to the spill.

Cleanup workers skimmed oil from the water’s surface, sprayed oil dispersant chemicals in the water and on shore, washed oiled beaches with hot water and rescued and cleaned animals trapped in oil.

Environmental officials purposefully left some areas of shoreline untreated so they could study the effect of cleanup measures, some of which were unproven at the time. They later found that aggressive washing with high-pressure, hot water hoses was effective in removing oil, but did even more ecological damage by killing the remaining plants and animals in the process. Nearly 30 years later, pockets of crude oil remain in some locations.Lessons Learned

A 2001 study found oil contamination remaining at more than half of the 91 beach sites tested in Prince William Sound.

The spill had killed an estimated 40 percent of all sea otters living in the Sound. The sea otter population didn’t recover to its pre-spill levels until 2014, twenty-five years after the spill.

Stocks of herring, once a lucrative source of income for Prince William Sound fisherman, have never fully rebounded.

In the wake of the Exxon Valdez oil spill, the U.S. Congress passed the Oil Pollution Act of 1990. The Oil Pollution Act of 1990 increased penalties for companies responsible for oil spills and required that all oil tankers in United States waters have a double hull. The Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA), which was enacted after the Exxon Valdez spill in 1989, established the Interagency Coordinating Committee on Oil Pollution Research (interagency committee) to coordinate oil pollution research among federal agencies and with relevant external entities, among other things.

The U.S. GAO recommends, among other things, that the interagency committee coordinate with the trustee councils to support their work and research needs

Exxon Valdez changed the oil industry forever—but new threats emerge

Thirty years ago, a spill in Alaska shocked the world. Tankers got safer, but they're not the only risks.

BY STEPHEN LEAHY NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

PUBLISHED MARCH 22, 2019

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CONTAINS INFOGRAPHICS

“My eyes were watering from the oil fumes even at 1,000 feet,” recalled Rick Steiner, who flew over the Exxon Valdez oil tanker on March 24, 1989, only hours after it had plowed into a cold-water reef. “Oil was all over the deck, and it was everywhere in the water,” said Steiner, who was the University of Alaska's marine advisor in the Prince William Sound region at the time.

The Exxon Valdez was the worst oil spill in U.S. waters until the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010. Within days oil from the Exxon Valdez spread some 1,300 miles along the coast of what was pristine wilderness. In the first days of the spill there was no oil recovery or clean-up equipment in the water, said Steiner, who is now a marine conservation consultant at the “Oasis Earth” project.

Eventually, massive clean-up efforts involving thousands of people were undertaken. The final death toll included 250,000 seabirds, almost 3,000 sea otters, 300 harbor seals, 250 bald eagles, 22 killer whales, and billions of salmon eggs. Populations of pacific herring, a cornerstone of the local fishing industry, collapsed. Fishermen went bankrupt.

It’s impossible to fully clean up an oil spill in the ocean, said Steiner, who’s been involved in many spills since 1989. And the impacts of these disasters can linger for decades. Thirty years later, local populations of killer whales and some seabirds in Prince William Sound have still not recovered, he said.

Some of the oil is still there, too. Recent sampling along the coast revealed pockets of oil buried four to eight inches under sand and gravel, often topped by stones. It’s likely to remain there for decades to come, according to a 2017 study by Jacqueline Michel, a geochemist specializing in oil spills, and president of Research Planning Inc.

A powerful storm or earthquake could potentially put that oil residue back into Prince William Sound, Michel said. However, digging up those residues to remove them would likely do more harm than good, she added.

Stricter laws reduce spills

In the wake of the Exxon Valdez disaster, the U.S. Congress passed a law, in 1990, that required oil tankers in U.S. waters to have double hulls (unlike that fateful ship) and increased penalties for spills. Today, all of the world’s fleet of 12,000 to 14,000 tankers for oil, liquefied natural gas (LNG), and chemicals are double hulled.

Combined with tougher regulations and better navigation equipment, oil spills releasing more than seven tons from tankers plummeted from a high of 79 spills per year in the 1970s to six per year over the past decade, according to ITOPF, an association of shipowners that responds to oil spills.

The decline in large spills greater than 700 tons was even more dramatic, falling from 24.5 per year to just two per year.

The biggest spills in histor

Perhaps surprisingly, given its notoriety and impact on the shipping industry, the Exxon Valdez spill was only the 36th worst tanker oil spill yet recorded. The biggest between 1970 and 2018 happened in 1979, off the coast of Tobago in the West Indies when the Atlantic Empress lost 287,000 tons of crude in a collision with another tanker. For comparison, the Valdez lost 37,000 tons. (There is roughly 305 gallons in a metric ton of oil.)

The worst tanker accident in the past 25 years occurred in January 2018, when two tankers collided off the coast of China. An Iranian oil tanker, the Sanchi,lost 117,000 tons of highly toxic natural gas condensate. None of Sanchi's 32 crew members survived.

By far the biggest accidental spill into the ocean was from the Deepwater Horizon oil drilling platform in the Gulf of Mexico. At 35,000 feet, it was the deepest well ever drilled until the blow out that killed 11 workers. Over nearly 90 days the broken well pumped 680,000 tons (approximately 5 million barrels) of oil into the Gulf. The spill cost oil company BP an estimated $61.6 billion, and they still couldn’t contain or recover all the oil that was spilled, said Michel, who worked on the project to assess some of the impacts.

Future risk?

Marine oil spill containment and recovery technology improved tremendously after the Valdez, but not much has changed for at least the last decade, the experts say. Spills can be located faster and their movements modelled more accurately, but full containment and cleanup remains, impossible Michel said.

It can also be difficult to prevent an undersea oil well from leaking. In 2004, Hurricane Ivan destroyed an oil platform in the Gulf operated by Taylor Energy. It’s still leaking 15 years later. Taylor is reported to have spent over $400 million working alongside the U.S. Coast Guard to contain and clean up the spill, but it’s been an ongoing challenge.

More and more oil drilling is being done offshore in deepwater off the U.S. and around the world. Last year, the Trump administration proposed opening up far more offshore areas to drilling

“Oil platform drilling in deeper water is the new paradigm of risk for oil spills in the marine environment,” said Michel.

US Congress allows oil spill tax to expire

Published date: 09 January 2019

A US government trust fund used to clean up oil spills is losing out on millions of dollars in revenue after lawmakers allowed a 9¢/bl excise tax on refiners, importers and producers to expire at the end of last year.

The tax is the main source of revenue for the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund, which was created in the wake of the 1989 Exxon Valdez disaster as a way to ensure the timely clean-up of oil spills. The tax applies to crude received at US refineries, imports of petroleum products and domestically produced crude that is exported.

But the US Congress allowed the tax to expire on 31 December, saving refiners and importers that would otherwise pay into the fund more than $1.5mn/d in taxes, based on recent refinery runs and import levels.

"Suspending the tax is a tax giveaway to the oil industry by this Congress and administration," said Rick Steiner, a retired professor at the University of Alaska and board member for the non-profit group Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility.

Congress similarly allowed the excise tax to expire at the end of 2017, creating a two-month gap in the tax's collection before it was reinstated on 1 March 2018 through a bipartisan budget law. It remains unclear how long it might take for lawmakers to reinstate the tax. A Democratic bill to reopen the government does not include an extension of the tax.

Tax experts say it is unlikely that Congress would make the oil spill excise tax retroactive, given that refiners and importers usually pass on the tax to their customers.

"I think it would be very, very unlikely to happen, especially based on the precedent last time," KPMG federal excise tax practice managing director Deborah Gordon said.

Environmental groups have pushed to broaden the excise tax so it applies to oil sands, which is now exempt from the tax, and to cargo ships, which are covered by the fund but do not pay the tax. The trust fund had a balance of $6.7bn as of the end of last year, up from $900mn nearly a decade ago, according to budget documents.

The US Coast Guard, which administers the fund, did not respond for comment.

SEE 1969 SANTA BARBARA OIL SPILL

Tags: Exxon Valdez, oil spill, spill prevention, spill response

Exxon Valdez changed the oil industry forever—but new threats emerge

Thirty years ago, a spill in Alaska shocked the world. Tankers got safer, but they're not the only risks.

BY STEPHEN LEAHY NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

PUBLISHED MARCH 22, 2019

ORIGINAL ARTICLE CONTAINS INFOGRAPHICS

“My eyes were watering from the oil fumes even at 1,000 feet,” recalled Rick Steiner, who flew over the Exxon Valdez oil tanker on March 24, 1989, only hours after it had plowed into a cold-water reef. “Oil was all over the deck, and it was everywhere in the water,” said Steiner, who was the University of Alaska's marine advisor in the Prince William Sound region at the time.

The Exxon Valdez was the worst oil spill in U.S. waters until the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010. Within days oil from the Exxon Valdez spread some 1,300 miles along the coast of what was pristine wilderness. In the first days of the spill there was no oil recovery or clean-up equipment in the water, said Steiner, who is now a marine conservation consultant at the “Oasis Earth” project.

Eventually, massive clean-up efforts involving thousands of people were undertaken. The final death toll included 250,000 seabirds, almost 3,000 sea otters, 300 harbor seals, 250 bald eagles, 22 killer whales, and billions of salmon eggs. Populations of pacific herring, a cornerstone of the local fishing industry, collapsed. Fishermen went bankrupt.

It’s impossible to fully clean up an oil spill in the ocean, said Steiner, who’s been involved in many spills since 1989. And the impacts of these disasters can linger for decades. Thirty years later, local populations of killer whales and some seabirds in Prince William Sound have still not recovered, he said.

Some of the oil is still there, too. Recent sampling along the coast revealed pockets of oil buried four to eight inches under sand and gravel, often topped by stones. It’s likely to remain there for decades to come, according to a 2017 study by Jacqueline Michel, a geochemist specializing in oil spills, and president of Research Planning Inc.

A powerful storm or earthquake could potentially put that oil residue back into Prince William Sound, Michel said. However, digging up those residues to remove them would likely do more harm than good, she added.

Stricter laws reduce spills

In the wake of the Exxon Valdez disaster, the U.S. Congress passed a law, in 1990, that required oil tankers in U.S. waters to have double hulls (unlike that fateful ship) and increased penalties for spills. Today, all of the world’s fleet of 12,000 to 14,000 tankers for oil, liquefied natural gas (LNG), and chemicals are double hulled.

Combined with tougher regulations and better navigation equipment, oil spills releasing more than seven tons from tankers plummeted from a high of 79 spills per year in the 1970s to six per year over the past decade, according to ITOPF, an association of shipowners that responds to oil spills.

The decline in large spills greater than 700 tons was even more dramatic, falling from 24.5 per year to just two per year.

The biggest spills in histor

Perhaps surprisingly, given its notoriety and impact on the shipping industry, the Exxon Valdez spill was only the 36th worst tanker oil spill yet recorded. The biggest between 1970 and 2018 happened in 1979, off the coast of Tobago in the West Indies when the Atlantic Empress lost 287,000 tons of crude in a collision with another tanker. For comparison, the Valdez lost 37,000 tons. (There is roughly 305 gallons in a metric ton of oil.)

The worst tanker accident in the past 25 years occurred in January 2018, when two tankers collided off the coast of China. An Iranian oil tanker, the Sanchi,lost 117,000 tons of highly toxic natural gas condensate. None of Sanchi's 32 crew members survived.

By far the biggest accidental spill into the ocean was from the Deepwater Horizon oil drilling platform in the Gulf of Mexico. At 35,000 feet, it was the deepest well ever drilled until the blow out that killed 11 workers. Over nearly 90 days the broken well pumped 680,000 tons (approximately 5 million barrels) of oil into the Gulf. The spill cost oil company BP an estimated $61.6 billion, and they still couldn’t contain or recover all the oil that was spilled, said Michel, who worked on the project to assess some of the impacts.

Future risk?

Marine oil spill containment and recovery technology improved tremendously after the Valdez, but not much has changed for at least the last decade, the experts say. Spills can be located faster and their movements modelled more accurately, but full containment and cleanup remains, impossible Michel said.

It can also be difficult to prevent an undersea oil well from leaking. In 2004, Hurricane Ivan destroyed an oil platform in the Gulf operated by Taylor Energy. It’s still leaking 15 years later. Taylor is reported to have spent over $400 million working alongside the U.S. Coast Guard to contain and clean up the spill, but it’s been an ongoing challenge.

More and more oil drilling is being done offshore in deepwater off the U.S. and around the world. Last year, the Trump administration proposed opening up far more offshore areas to drilling

“Oil platform drilling in deeper water is the new paradigm of risk for oil spills in the marine environment,” said Michel.

US Congress allows oil spill tax to expire

Published date: 09 January 2019

A US government trust fund used to clean up oil spills is losing out on millions of dollars in revenue after lawmakers allowed a 9¢/bl excise tax on refiners, importers and producers to expire at the end of last year.

The tax is the main source of revenue for the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund, which was created in the wake of the 1989 Exxon Valdez disaster as a way to ensure the timely clean-up of oil spills. The tax applies to crude received at US refineries, imports of petroleum products and domestically produced crude that is exported.

But the US Congress allowed the tax to expire on 31 December, saving refiners and importers that would otherwise pay into the fund more than $1.5mn/d in taxes, based on recent refinery runs and import levels.

"Suspending the tax is a tax giveaway to the oil industry by this Congress and administration," said Rick Steiner, a retired professor at the University of Alaska and board member for the non-profit group Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility.

Congress similarly allowed the excise tax to expire at the end of 2017, creating a two-month gap in the tax's collection before it was reinstated on 1 March 2018 through a bipartisan budget law. It remains unclear how long it might take for lawmakers to reinstate the tax. A Democratic bill to reopen the government does not include an extension of the tax.

Tax experts say it is unlikely that Congress would make the oil spill excise tax retroactive, given that refiners and importers usually pass on the tax to their customers.

"I think it would be very, very unlikely to happen, especially based on the precedent last time," KPMG federal excise tax practice managing director Deborah Gordon said.

Environmental groups have pushed to broaden the excise tax so it applies to oil sands, which is now exempt from the tax, and to cargo ships, which are covered by the fund but do not pay the tax. The trust fund had a balance of $6.7bn as of the end of last year, up from $900mn nearly a decade ago, according to budget documents.

The US Coast Guard, which administers the fund, did not respond for comment.

SEE 1969 SANTA BARBARA OIL SPILL

Tags: Exxon Valdez, oil spill, spill prevention, spill response

No comments:

Post a Comment