In an excerpt from the book Killer High, author Peter Andreas lays out how the opium poppy has been funding political parties and conflict for generations, often with the CIA’s tacit approval

Peter Andreas Published: 14 Feb, 2020

By the early 1930s, China was estimated to be the source of seven eighths of the world’s narcotics supply, which reached international markets via Hong Kong, Macau and Shanghai. British journalist H.G.W. Woodhead described the situation in a detailed investigation: “In general it may be stated that throughout China today with the exception of isolated instances, no effort is or can be made by the National Government to control the sale or smoking of opium. It can be purchased without difficulty, in practically every town and village of any size throughout the country. And the traffic is controlled by the military and big opium rings.”

The government also illicitly exported narcotics to the United States and elsewhere to generate foreign exchange to pay for military supplies, including major aircraft purchases. Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang used opium suppression as a tool to attack rivals, especially targeting areas of communist activity. In June 1934, Chiang announced the Six Year Opium Suppression Plan, with the stated aim of total eradication of the drug within six years. The new military-enforced prohibition policy included the execution of thousands of drug offenders.

The Six-Year Plan was a means to ensure that the government would exercise complete control over the opium economy while simultaneously depriving regional political rivals in the southwest of opium funds. The Japanese occupation of Shanghai, in August 1937, diminished but did not end Kuomintang influence over the opium trade, and its alliance with the criminal underworld remained as strong as ever.

Having used opium to help finance their revolution, after taking power on October 1, 1949, Mao Zedong’s triumphant communists quickly moved to eradicate it. On February 24, 1950, the new government issued its General Order for Opium Suppression, which begins: It has been more than a century since opium was forcibly imported into China by the imperialists. Due to the reactionary rule and the decadent lifestyle of the feudal bureaucrats, compradors and warlords, not only was opium not suppressed, but we were forced to cultivate it; especially due to the Japanese systematically carrying out a plot to poison China during their aggression, countless people’s lives and property have been lost. Now that the people have been liberated, the following methods of opium and other narcotic suppression are specifically stipulated to protect people’s health, to cure addiction, and to accelerate production.

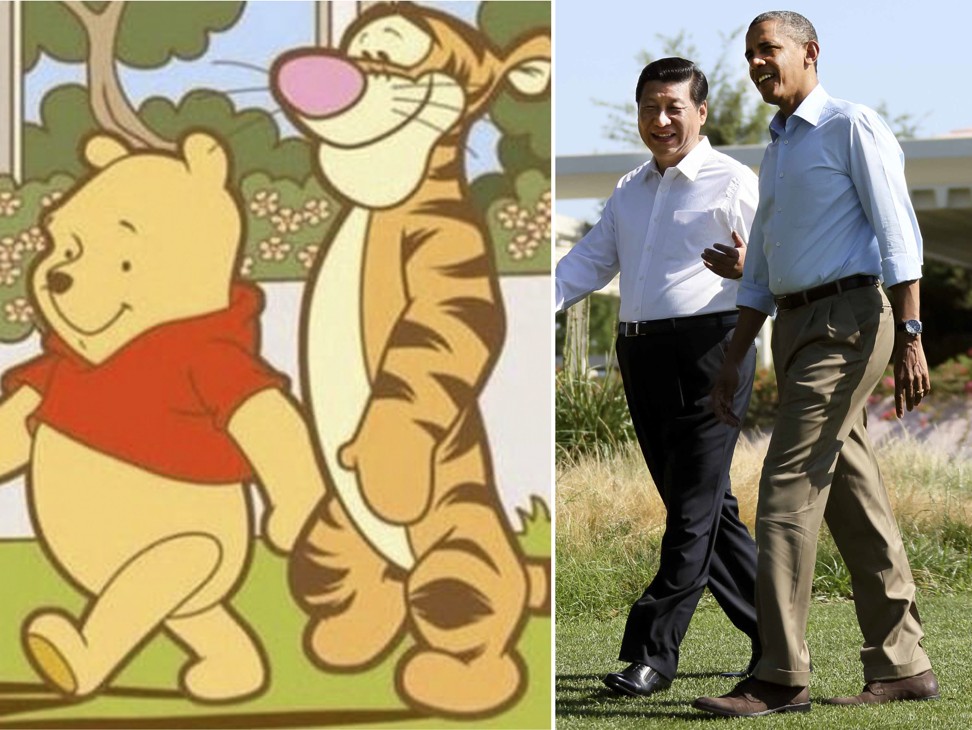

Opium smokers joke around and pose in their “den” in Shanghai, in 1898. Photo: Getty Images

Chinese anti-drug rhetoric was wrapped up in the larger revolutionary cause – to be against opium was to be against foreign imperialism and capitalist decadence. The post-revolution movement targeting “capitalist vices” included rounding up and executing thousands of drug dealers and forcing addicts to choose between treatment or imprisonment. In 1952 alone, the crackdown generated 82,000 arrests, 35,000 prison sentences and 880 public executions. The Central Committee told local authorities that “it is easier to get people’s sympathy by killing drug offenders than killing counter-revolutionaries. So at least 2 per cent of those arrested should be killed”.

By 1953, China’s post-revolution exit from the opium trade prompted a fundamental reconfiguration of the political economy of narcotics in the region. Major traffickers, including the Shanghai underworld leadership, fled the country, with many of them relocating to Hong Kong – master chemists who would turn the colony into the world’s leading high-grade heroin laboratory.

Opium production also shifted. Along with Nationalist forces, opium cultivation was pushed south – out of China and into remote borderland areas of Burma, Laos and Thailand, which would later be called the Golden Triangle. An area that until the 1950s produced only modest amounts of opium would in the next decade become the world’s single largest supplier of the drug. By the end of that decade, it would produce about 700 tonnes of raw opium annually – about half of the world’s supply.

The rugged, isolated hills and mountains of northern mainland Southeast Asia were already populated by tribes with knowledge of opium production, including the Hmong, who had fled southern China a century earlier after rebelling against Chinese rule. The terrain, located far from the reach of central government authorities, was ideal for an expansion of opium poppy cultivation. Secretly backed by the US’ Central Intelligence Agency starting in the early 1950s, the retreating Chinese Nationalists, already adept at using dope money to fund their military cause, now turned again to opium to carry out their anti-communist military operations along the southwestern Chinese border.

To fight you must have an army and an army must have guns, and to buy guns you must have money. In these mountains the only money is opiumGeneral Tuan Shi-wen, Nationalist commander

These rebel remnants of the Kuomintang, operating in exile in Burma’s Shan State, not only received clandestine military supplies from the CIA-owned Civil Air Transport (later renamed Air America) but also used this politically protected fleet of small aircraft as a cover for drug shipments. The force soon swelled to a 12,000-strong guerilla army, the leaders of which served as de facto rulers over the area – an area that happened to be Burma’s main source of opium. The strategic importance of opium was not difficult to understand. “To fight you must have an army,” said General Tuan Shi-wen, a veteran Nationalist commander in Burma, “and an army must have guns, and to buy guns you must have money. In these mountains the only money is opium.

Read more

Young American’s first-hand account of second opium war

Read more

Why Hong Kong’s family fortunes stem from the opium trade

While the Chinese Nationalists failed to realise their dream of retaking China – their multiple invasions of Yunnan province were easily driven back by the Red Army – they succeeded in turning the Golden Triangle into the world’s largest opium-poppy-growing area by the early 1960s. In 1960-61, Chinese and Burmese military campaigns drove many of the exiles to neighbouring Laos and Thailand, and from there, they continued to move opium out of the Shan State via mule caravans, controlling nearly one-third of world opium supplies by the early 1970s.

They also enabled the emergence of local opium warlords, most notably Khun Sa, who would use his own private army to dominate much of the trade in later years. Military rulers in neighbouring Thailand also facilitated and profited from the opium boom, with Bangkok providing not only a consumer base but also serving as a regional distribution centre and outlet to the rest of the world

Having occupied Shan State during World War II, Thai leaders had already built close ties to local warlords and the Kuomintang across the border. So when the war came to an end, the Thai government already had the requisite relations to engage in the opium business, which it would use to help bankroll its armed forces.

After taking power in an opium-financed coup in 1947, the country’s military rulers and subsequent military regimes financed themselves through the opium trade. General Phao Sriyanond, the head of the CIA-trained and -supplied national police force, was also the de facto head of the opium trade, and helped to create and protect the Kuomintang’s Burma-Bangkok opium-smuggling route. According to historian Alfred McCoy, by the mid-1950s, Phao’s police had become the biggest opium-trafficking organisation in the country. The CIA provided Phao with the vehicles used to transport his dope from field to port.

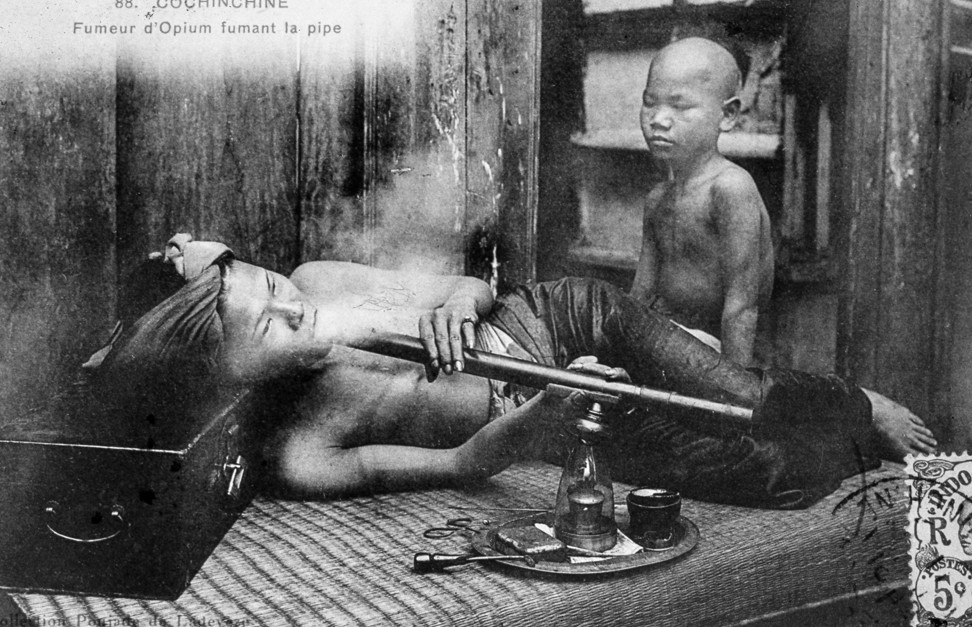

An undated picture of an opium den in IndoChina. Photo: Getty Images

The CIA became more deeply entangled in the region’s drug trade after the French military defeat in Indochina in 1954. Colluding with Corsican traffickers who shipped opium from Indochina to Marseille, the French intelligence service had used opium funds to covertly pay local hill tribe leaders and warlords as part of its counter-insurgency campaign. Earlier, French colonial administrators had run an opium monopoly, with some 2,500 opium dens and retail shops serving more than 100,000 consumers in Indochina by the start of World War II.

The French monopoly was closely associated with colonial rule, and it was therefore a favourite target of nationalist anticolonial voices. Ho Chi Minh effectively exploited popular resentment against the French opium monopoly in his propaganda. To compensate for the cutting off of foreign opium supplies and opium revenue during World War II, the French encouraged the Hmong hill tribes of Laos and the Tonkin people of northwest Indochina to boost opium poppy cultivation, offering them political support in exchange for their cooperation. Production shot up 800 per cent, from fewer than eight tonnes in 1940 to more than 60 tonnes in 1944.

When French colonial administrators formally ended their opium monopoly after the war, French military intelligence informally took it over to finance their covert campaign in the first Indochina War of 1946-1954. This secret revenue stream from what came to be known as “Operation X” was especially needed after the French Assembly cut back its funding in the midst of dwindling public support at home for an unpopular distant military campaign. Opium funding helped the French slow down Viet Minh advances even if it ultimately failed to revive a dying empire and change the outcome of the war.

When the French withdrew after their defeat at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, the CIA simply stepped in and took their place, building on the inherited opium trade relationships and infrastructure. This included supporting the same Hmong-based secret army in Laos headed by General Vang Pao, whose soldiers provided intelligence and battled Laotian communists near the North Vietnamese border. In exchange the CIA helped ship their opium out of the remote and difficult-to-access region. The covert war in Laos required only a handful of CIA advisers, with the cost of supporting 30,000 Hmong troops (and a tribe of 250,000 to replenish battlefield losses with new recruits) cushioned by opium sales.

The battle at Dien Bien Phu, in 1954, precipitated the collapse of French colonial rule in Indochina. Photo: Getty Images

Senior US officials back at the CIA’s Washington headquarters were not inclined to pay too much attention as long as Hmong loyalty was secured and the operation was producing results. As American intervention escalated and the war in Vietnam dragged on, CIA-backed anti-communist allies in the region increasingly profited from opium and its derivatives, with the Cold War context providing the necessary political cover. As McCoy documents in detail in his classic book The Politics of Heroin (1972), the CIA was complicit not through corruption or direct involvement, but rather through what he describes as a radical pragmatism that tolerated and even facilitated drug trafficking by local allies when it served larger Cold War goals.

By 1970, more than two-thirds of the world’s opium came from the Golden Triangle, and the region would retain this status of top producer until the end of the Cold War. The region’s drug trade received an additional boost from the presence of American GIs, who in the early 1970s developed a serious heroin habit.

With the help of master chemists brought in from Hong Kong, by the late 60s Golden Triangle laboratories were for the first time producing fine-grain No 4 heroin (the classification for drugs of 80 to 99 per cent purity). Previously, production had mostly been confined to refined opium or the lower quality No 3 heroin (20 to 40 per cent purity). Politically protected traffickers, including senior Laotian and Vietnamese military officials, supplied the American troops in Vietnam, who numbered half a million at the peak of the conflict. Some of these soldiers in turn helped to smuggle thousands of kilos into the US through conveyances ranging from GI care packages to body bags.

Most of the heroin was flown from the remote reaches of the Golden Triangle into Vietnam on Lao and South Vietnamese military aircraft, overseen by corrupt senior officials. Later, the head of the Vietnamese navy, General Dang Van Quang, would use his fleet to ship heroin from Cambodia. It was easy to reach consumers. As historian Martin Booth notes, “Heroin was available at roadside stalls on every highway out of Saigon, and on the route to the main US military base at Long Binh, as well as from itinerant peddlers, newspaper and ice-cream vendors, restaurant owners, brothel keepers and their whores and domestic servants employed on US bases. No barracks was without a resident dealer.”

Most soldiers preferred to smoke rather than inject the drug, a method of ingestion made possible by high purity levels. In mid 1971, US Army medical officers estimated that some 10 to 15 per cent of the deployed rank-and-file troops were heroin addicts. In 1973, the Pentagon estimated that one-third of American servicemen in Vietnam used heroin.

American troops arrive in Vietnam, in 1965. Photo: Getty Images

Following earlier patterns in Southeast Asia, Washington looked the other way when CIA-backed Afghan insurgents battling the Soviets in the 1980s cultivated and smuggled opium to help fund their cause. In the CIA’s biggest covert operation since Vietnam, the opium trade was once again one of the biggest winners. As McCoy summarises, “To fight the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, the CIA, working through Pakistan’s Inter-Service Intelligence, backed Afghan warlords who used the agency’s arms, logistics and protection to become major drug lords.”

US officials were apparently well aware of the situation but turned a blind eye in pursuit of larger geopolitical goals. “We’re not going to let a little thing like drugs get in the way of the political situation,” explained a Reagan administration official at the time. “And when the Soviets leave and there’s no money in the country, it’s not going to be a priority to disrupt the drug trade.” When the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in late 1979, opium cultivation was a marginal activity compared with later years.

Opium had long been present in what came to be known as the Golden Crescent – Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran. Zahiruddin Muhammad Babur, founder of the Mughal Empire, had written about using opium when he sacked Kabul in 1504, and the drug was being consumed socially across the region by the mid-16th century. But until the late 1970s the market was mostly self-contained, supplying local and regional customers and largely disconnected from the global heroin trade. All this changed thanks to the war-ravaged years of the 1980s and beyond, with Afghanistan eventually coming to dominate world opium production.

The Soviet Union’s scorched-earth strategy in the Afghan countryside, designed to starve the mujahideen resistance and force rural populations into more easily controllable urban centres, destroyed much of the infrastructure for food production. In addition to creating millions of refugees who fled to neighbouring Pakistan and Iran, an unintended consequence of this strategy was to push the local population to grow opium to survive.

Compared with many other crops, the hardy opium poppy could adapt to varied terrain and required little irrigation and fertilisation. Opium production increased by more than twofold between 1984 and 1985 – from an estimated 140 tonnes to 400 – and then doubled again the next year. By 1987, overall agricultural production was only one-third of 1978 levels, but opium cultivation had boomed. Mujahideen commanders became increasingly enmeshed in the opium trade.

Opium harvest in Burma in March 1982. Picture: Getty Images

This involvement ranged from taxing and protecting crops to imposing road tolls on traders at checkpoints to smuggling opium out of the country through the same channels used to smuggle in arms supplied by the CIA and Pakistan’s Directorate of InterServices Intelligence (ISI). Indeed, a fleet of trucks belonging to the Pakistani army’s National Logistics Cell was allegedly used to move CIA-provided arms into the country and then move opium and heroin out on the return trip. ISI documents assured those involved that the trucks would not be searched and seized by Pakistani police.

By 1988, there were as many as 200 heroin laboratories in Pakistan’s North-West Frontier Province’s Khyber district alone. The heroin was not only exported to Europe and elsewhere but fed Pakistan’s rapidly growing demand – a country that in the late 1970s did not have a serious heroin abuse problem soon had one of the largest addict populations in the world, skyrocketing from about 5,000 in 1980 to more than 1.3 million in the middle of the decade.

Immediate military necessity overcame whatever religious qualms mujahideen leaders may have had about supporting the drug trade. “How else can we get money?” asked Mohammed Rasul, brother of the Helmand province warlord Mullah Nasim Akhundzada. “We must grow and sell opium to fight our holy war against the Russian nonbelievers.” The Akhundzada family not only taxed opium crops but set up a system of production quotas and loans to farmers to induce them to grow opium poppies. Some mujahideen became directly involved in morphine and heroin manufacturing along the Pakistani border. They included Akhundzada’s main rival, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, an ISI protégé from the fundamentalist Hizb-i-Islami Party who received more than half of all CIA assistance to the anti-Soviet resistance.

“All the big traffickers in those days tended to be from Hizb-i-Islami and that was principally because Hekmatyar was a border person,” recalled Edmund McWilliams, a special envoy to the resistance between 1988 and 1989. “He was very much operating along the border because he was so dependent on Pakistani support.”

With CIA and Pakistani intelligence backing, Hekmatyar built up his small guerilla force into the largest Afghan resistance army. He simultaneously became the country’s most important drug trafficker, controlling half a dozen heroin laboratories in the Koh-i-Soltan district of Pakistan’s Baluchistan province, where opium brought in from Afghanistan’s Helmand Valley was processed. American officials at the time preferred to look the other way because it was simply too politically inconvenient to do otherwise. “You have to put yourself in the mindset of the period,” McWilliams said. “Raising issues like Hekmatyar and the ISI’s involvement in the drug trade was on no one’s agenda.”

You have to put yourself in the mindset of the period. Raising issues like Hekmatyar and the ISI’s involvement in the drug trade was on no one’s agendaEdmund McWilliams, diplomat

In 1990, after the Soviets were gone and Afghanistan had lost its strategic importance, The Washington Post ran a front-page story detailing Hekmatyar’s heroin operations and reported that US diplomats had “received but declined to investigate” on-the-ground accounts that Afghan fighters and Pakistani intelligence agents were “protect[ing] and participat[ing]” in the heroin trade. The article indicated that the US had turned a blind eye “because of its desire not to offend a strategic ally, Pakistan’s military establishment”.

“One of my great frustrations at the time was that the CIA would not give us information on narcotics,” said former US ambassador to Pakistan Robert Oakley. “My belief was then and still is that they wanted to protect their contacts in Pakistani intelligence.” Afghan dependence on the opium trade only deepened as the Soviet Union withdrew in early 1989. Agricultural recovery in the countryside was most evident in the drug trade: “Much of this renewed production took the form of opium growing, heroin refining and smuggling; these enterprises were organised by combines of mujahideen parties, Pakistani military officers and Pakistani drug syndicates,” wrote prominent Afghan expert Barnett Rubin.

The labour-intensive opium business found easy recruits among the millions of desperate Afghan refugees repatriated from Pakistan. With US assistance drying up, the countryside devastated by a brutal decade-long counter-insurgency campaign, and no effective government authority, Afghanistan descended into civil war in the early 1990s. The Soviet-supported government of Mohammad Najibullah, which was never able to exercise much control beyond Kabul or win support beyond its own ethnic base in the northeast, fell in April 1992.

Replaying some of the dynamics of China’s early-20th century warlord era of extreme political fragmentation, former mujahideen commanders brutally competed with each other over territory, especially the best opium land – except in this case, the market for the drug was external rather than internal, and there was no pretence of opium suppression. Mullah Nasim Akhundzada, for instance, oversaw most of the 250 tonnes of opium grown in the fertile Helmand Valley and was nicknamed the “King of Heroin”. He imposed an opium quota and insisted that peasant growers devote half of their land holdings to the cultivation of the opium poppy.

His competition with rival leader Hekmatyar intensified, and in April 1990 Nasim was gunned down by Hekmatyar-allied troops. He was replaced by his brother, Mohammed Rasul, who maintained the family’s grip on much of the Helmand Valley. These former mujahideen factions, more preoccupied with fighting each other over control of the opium economy and building up their own personal fiefdoms than in uniting and governing the country, ultimately proved no match for the Taliban, a Pakistan-backed ultraconservative movement originating in the Islamic academies (madrasas) of the Afghan-Pakistani frontier region.

Afghan anti-Taliban fighters in eastern Afghanistan, in 2001. Photo: AFP

Opium contributed to the Taliban’s rapid rise to power out of the chaos and violent predation of the early 1990s. In its campaign to pacify the country and impose an extreme interpretation of Islam, the Taliban initially sought to ban opium cultivation on religious grounds. But faced with intense popular resistance rooted in the livelihood the poppy provided to so many, the group reversed course and came to not only tolerate but promote the opium economy.

It banned the consumption of opiates, as well as alcohol and other drugs, but allowed the production and trading of opium. This generated not only revenue for the Taliban cause but, perhaps most importantly, much-needed popular support, given how important the opium economy was to local sustenance. Before capturing Kabul, the Taliban systematically conquered key opium-growing areas, including Kandahar and Helmand in the south in 1994 (the source of 56 per cent of the country’s opium), Herat in 1995, and Jalalabad and the eastern opium-growing region in 1996 (the source of 39 per cent of the country’s opium).

The Taliban’s primary rival, the Northern Alliance, was also involved in the opium trade (as well as other illicit trades, especially the smuggling of gemstones) but was disadvantaged by the fact that areas under its control represented only a small percentage of the country’s overall cultivation. Once in power, the Taliban regime not only continued to allow the cultivation of the opium poppy – and continued to systematically tax it (collecting a 10 per cent tax from farmers at the point of production and a 20 per cent tax on truckloads of opium at the point of export) – but provided some semblance of stability for the illicit trade to greatly expand.

While failing to provide some of the basic services of a full fledged state, the Taliban was able to impose its authority over most of the country’s roads, urban centres, airports and customs posts, and this modicum of security and stability benefited cross-border traders, including opium exporters.

By the end of the decade, Afghanistan had become the source of three-quarters of the world’s supply of opium, with areas under Taliban control in the south and east producing virtually all of the country’s poppy crop. Such flagrant support for the booming opium trade contributed to the Taliban’s growing international pariah status and reputation as a “narcostate”. And opium in turn helped to sustain a defiant Taliban in the face of growing international isolation. Few countries recognised it as Afghanistan’s legitimate government. But it was the Taliban’s hospitality toward terrorists, not drug traffickers, that would ultimately bring it down – and it was opium that would help build it back up.

Afghan children sit along the edge of a poppy field in the Tora Bora region of Afghanistan. Photo: AP

The US invaded Afghanistan in October 2001 in retaliation for the

September 11 terrorist attacks. The target was not only those responsible for bringing down the Twin Towers – Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda – but their hosts and protectors, the Taliban regime. While the US dropped bombs from the air, it paid a coalition of local warlords to lead the ground attack. This coalition, funded by the CIA, included both a group of Pashtun warlords near the Pakistani border and the Northern Alliance, a Tajik army with experience fighting the Soviets in the 1980s and the Taliban during the next decade. Both controlled opium-smuggling routes in their respective territories. In other words, following the old Cold War pattern, the US was once again more than willing to work with drug traffickers when it served larger strategic goals.

The Taliban collapsed and scattered into the countryside while bin Laden disappeared into the jagged Tora Bora Mountains. Although the Taliban had implemented a sweeping opium ban during its final year in power – apparently to try to win international recognition and respect, but also perhaps to drive up drug prices and benefit from stockpiled heroin – opium production made a dramatic comeback in the aftermath of the invasion, making up an estimated 62 per cent of Afghanistan’s gross domestic product in 2003. By the end of 2004, it was not only the drug trade but also the Taliban that was resurgent, and the two would become increasingly intertwined.

US officials initially paid little attention to the revival of the drug trade in Afghanistan but eventually came to push for an aggressive eradication campaign in the countryside. But by this time, opium cultivation was as entrenched in the rural economy as ever, and suppression efforts had the perverse and unintended consequence of driving the disgruntled local population right into the hands of the Taliban. Thus, the inescapable conundrum facing the US and its allies was not only that opium was funding the guerillas, but going after opium was creating new guerilla recruits.

By 2007, opium production had reached record levels, with the United Nations estimating that Afghanistan was the source of 93 per cent of the world’s illicit heroin supply. The UN also noted that the Taliban insurgents had “started to extract from the drug economy resources for arms, logistics, and militia pay”. In 2008 alone, “taxes” on the opium trade reportedly generated US$425 million for the Taliban.

To make matters worse, the US also found itself backing an extraordinarily corrupt government in Kabul, one that also had deep ties to drug trafficking. As had been the case during the Cold War, a pragmatic calculus meant Washington was willing to overlook such ties and perhaps even take advantage of them. For instance, Ahmed Wali Karzai, the brother of the new Afghan president, was widely suspected of ties to the heroin trade before he was assassinated, but he was also allegedly on the CIA payroll.

Commander of US and Nato forces in Afghanistan Scott Miller (right) with Afghanistan's acting defence minister Asadullah Khalid (centre), in 2019. Photo: AFP

The US also turned a blind eye to the appointment of Asadullah Khalid as the Afghani director of the National Directorate of Security. Khalid was a former governor of Kandahar and was widely accused of “abuses of power”, including murder, torture and drug trafficking. The US and its allies did not act on these allegations because, as Vanda Felbab-Brown, an expert on international organised crime, puts it, “whatever his accountability deficiencies, Khalid had a proven record of being tough on the Taliban”.

At the same time, the US faced blowback from its earlier backing of drug-dealing allies. This was embarrassingly evident in the case of the Haqqani network in Afghanistan and Pakistan, whose criminal activities included drug smuggling. This network had enjoyed covert CIA support while fighting Soviet forces in the 1980s, but in 2011 it was responsible for orchestrating a bold day-long attack on the American embassy in Kabul and was described as the most dangerous security threat to US forces in Afghanistan.

As one press report put it, in the 1980s the network had been supplied with US missiles; now it was the target of CIA missiles. Texas representative Charlie Wilson, whose support for the mujahideen was the subject of the film Charlie Wilson’s War (2007), had even described the elder Haqqani leader, Jalaluddin Haqqani, as “goodness personified”.

Fifteen years after the US invasion of Afghanistan – with Washington having spent more than US$1 trillion and counting on military operations – the war had no end in sight. The Taliban’s control over the drug trade continued to grow, expanding to cover much of Helmand province, the heart of poppy cultivation in southern Afghanistan. But even in those Helmand districts where the government remained in charge, opium not only grew openly near military and police stations but was taxed by the local authorities.

Despite the US spending billions of dollars on anti-drug efforts and billions more to curb corruption, local government officials had become so complicit in the drug trade that they were now apparently competing with the Taliban to profit from it. While the central government in Kabul repeatedly declared its commitment to fighting drugs and corruption, the reality on the ground in Helmand, as reported in The New York Times, was “a local narcostate administered directly by government authorities”.

Even though most of the drug profits may have stayed in the hands of local officials, payoffs reached up to the regional and national levels. Those complicit included key regional security and law enforcement commanders with ties to US military and intelligence officials. “Over the years, I have seen the central government, the local government and the foreigners all talk very seriously about poppy,” observed Hakim Angar, a former head of police in Helmand province. “In practice, they do nothing, and behind the scenes, the government makes secret deals to enrich themselves.”

The centuries-old relationship between opium and war has been first and foremost about generating revenue, whether to fund imperial expansion, prop up warlord ambitions or pay for insurgency and counter-insurgency campaigns. The shifting legal status of the drug, including its worldwide criminalisation in the 20th century, brought with it a more covert role as a funder of war. Consequently, the business of war and the business of crime became much more intertwined.

Killer High: A History of War in Six Drugs, by Peter Andreas, is published by Oxford University Press.