Xi Jinping, Winnie the Pooh and the Canadian origins of the bear that’s banned in ChinaXi Jinping

Comparisons between the beloved character and the Chinese president might have gone viral, but few are aware that Winnie’s story began in Canada during World War I

Patrick Blennerhassett

Published: 30 Dec, 2019

While most are now familiar with satirical comparisons of Chinese President Xi Jinping and popular children’s cartoon character Winnie the Pooh, fewer may know that the lovable bear’s origins lead all the way to a heartland Canadian city during the first world war.

Now, for the first time since “

Xi the Pooh” took root in 2013 – leading to Winnie’s likeness being banned in China, whether as a stuffed toy, paper mask or social-media sticker – the author of two books on the bear’s history, and great-granddaughter of Winnie’s original owner, has spoken about the bear’s enduring worldwide popularity (except, you know, in that one place).

“It is so outrageous and absurd,” says Canadian Lindsay Mattick, whose award-winning children’s books are still available in China despite the controversy. “To ban something like Winnie the Pooh, one of the most loving, peaceful and happy stories of all time, is really quite sad.”

Lindsay Mattick, the great-granddaughter of Harry Colebourn, Winnie’s original owner, and author of the book Finding Winnie. Photo: Lindsay Mattick

In 1914, a trainload of military men pulled into White River, Ontario, on their way to training in Quebec before heading to the war in Europe. During the brief stop, a 27-year-old Canadian soldier, Harry Colebourn, originally from England, made a purchase from a trapper: a black bear cub.

The trapper had killed the mother but said he could not do the same to its cub. Smitten, Colebourn handed over some cash and dubbed the female cub Winnie, after his adopted hometown of Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Colebourn took Winnie to England, where she became the regimental mascot of the Canadian Army Veterinary Corps before, realising the severity of the fighting, he reluctantly gave her to London Zoo. Winnie went on to become a star attraction, catching the eye of a little boy called Christopher Robin Milne, who renamed his teddy bear Winnie in her honour.

The trapper had killed the mother but said he could not do the same to its cub. Smitten, Colebourn handed over some cash and dubbed the female cub Winnie, after his adopted hometown of Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Colebourn took Winnie to England, where she became the regimental mascot of the Canadian Army Veterinary Corps before, realising the severity of the fighting, he reluctantly gave her to London Zoo. Winnie went on to become a star attraction, catching the eye of a little boy called Christopher Robin Milne, who renamed his teddy bear Winnie in her honour.

His bear and other toy animals would inspire his father, author A.A. Milne, in 1926 to create Winnie-the-Pooh (“Pooh” was Christopher Robin’s name for a swan), one of the world’s most beloved children’s characters, appearing in four books and, half a century later, in Walt Disney’s world-famous animation

Mattick discovered her great-grandfather’s connection to the stories as a child, while reading his diary with her family. In 2015 she published the children’s picture book Finding Winnie: The True Story of the World’s Most Famous Bear, winner of the Caldecott Medal in 2016. The book tells the story of Winnie and Harry and then Winnie and Christopher Robin. (Her second book, Winnie’s Great War, was published in 2018.)

“She was at the London Zoo for 20 years,” Mattick says. “She had a very friendly, docile nature, which is not the norm for a bear. But I would like to think that she got off on the right foot with my great-grandfather, who really loved animals and cared for her.”

The cartoon version of Winnie the Pooh first appeared in 1977, in Disney’s The Adventures of Winnie the Pooh, about the lovable bear and his animal friends – Piglet, Eeyore, Kanga, Roo, Rabbit and Tigger.

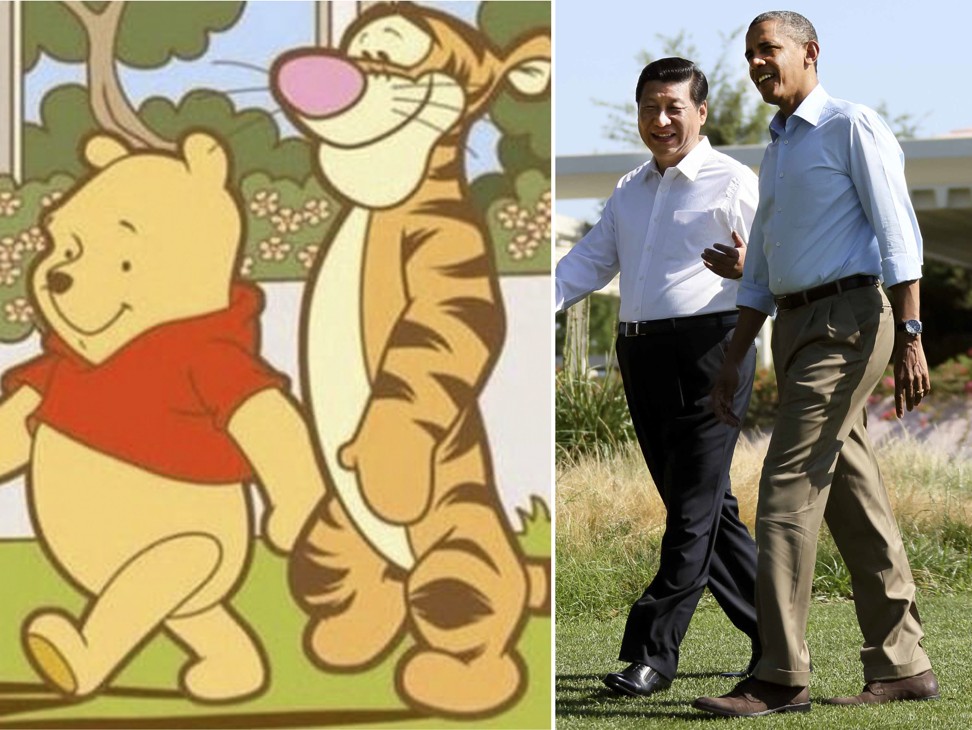

For the next few decades, Winnie the Pooh and his cohort were universally beloved. Then in 2013, Mattick, who runs her own public relations company in Toronto, caught wind of a bizarre case of anti-Winnie-ism. A photo had surfaced online of Xi and United States president Barack Obama next to a picture of similarly positioned cartoon characters, likening Obama to Tigger and Xi to Winnie the Pooh.

The Reuters image of Chinese President Xi Jinping with then US President Barack Obama next to a picture of Winnie the Pooh and Tigger that went viral on Weibo in 2013. Photo: Xinhua

The Reuters photo of the two leaders was taken during a summit in Sunnylands, California, but the source of the split shot is unknown. It soon went viral on Weibo, China’s ersatz answer to Twitter. Pictures were quickly deleted by censors, who apparently did not appreciate the comparison of the Chinese president to a bashful, hapless, chubby yellow bear.

When Mattick heard the news, she had a tough time wrapping her head around it. She did not do any media interviews, but she did receive a lot of messages from friends and family about the rather odd news that the leader of a country could be so thin-skinned as to think Winnie the Pooh posed a threat.

China’s Winnie the Pooh ban has since extended to the release of

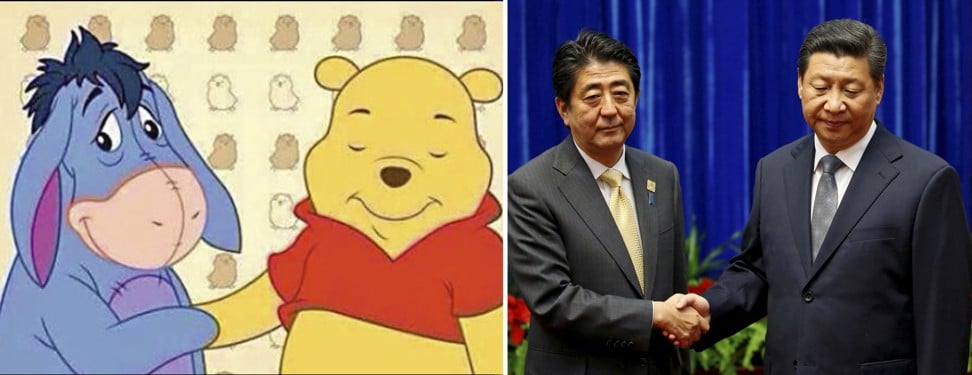

Christopher Robin , a 2018 film starring Ewan McGregor as the boy who fell in love with Winnie. While censoring the image in China is one aspect of the story, it has given the meme a life outside the mainland. Internet users continue to link images of Xi to Winnie the Pooh, including one in 2014 with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe filling in as Pooh’s melancholy donkey pal, Eeyore.

Of course, this is not the only thing the Chinese government has deemed unsuitable for its citizens. A long list of entertainment-related images, books, memes and shows have been banned over the years, the latest being the satirical US cartoon

South Park, after a recent episode took a dig at China.

The image of Eeyore and Winnie the Pooh that proliferated after comparisons were drawn between Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Xi and the two cartoon characters. Photo: Reuters

Vancouver-based University of British Columbia professor Florian Gassner, who specialises in the role of censorship in society, says Beijing’s actions have had both intended and unintended consequences. He says it is important to remember the target of this ban is internal, not external.

“And we should probably not forget that a lot of citizens in China support the Communist Party,” Gassner says. “When they see their government strike something down like this, it could be interpreted as the system working.”

It’s a trend Gassner has been seeing in authoritative countries where censorship has been taken to a new level, from India’s online troll armies to Russia’s state media. “The part that fascinates me is that governments are not capitulating, they are doubling down, doing their best to get all of this under control,” he says.

Mattick, who has held exhibitions about Winnie’s origins, says she hopes families in China can still enjoy the stories the bear has inspired, given their positive messages.

“I hope the Chinese population has the chance to not only read about the story but feel good about the story and feel proud about sharing it with their children without feeling like they are doing something subversive,” she says. “I feel sad that this particular chain of events has led to such a mixed perception that doesn’t seem in any way keeping with the spirit of the books and the stories.”

Patrick Blennerhassett is an award-winning Canadian journalist and four-time published author. He is a Jack Webster Fellowship winner and a British Columbia bestselling novelist. His work has been published in The Guardian, Reader's Digest, The Globe & Mail, Business Insider, MSN and his commentary has appeared on the BBC and the CBC.

The image of Eeyore and Winnie the Pooh that proliferated after comparisons were drawn between Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Xi and the two cartoon characters. Photo: Reuters

Vancouver-based University of British Columbia professor Florian Gassner, who specialises in the role of censorship in society, says Beijing’s actions have had both intended and unintended consequences. He says it is important to remember the target of this ban is internal, not external.

“And we should probably not forget that a lot of citizens in China support the Communist Party,” Gassner says. “When they see their government strike something down like this, it could be interpreted as the system working.”

It’s a trend Gassner has been seeing in authoritative countries where censorship has been taken to a new level, from India’s online troll armies to Russia’s state media. “The part that fascinates me is that governments are not capitulating, they are doubling down, doing their best to get all of this under control,” he says.

Mattick, who has held exhibitions about Winnie’s origins, says she hopes families in China can still enjoy the stories the bear has inspired, given their positive messages.

“I hope the Chinese population has the chance to not only read about the story but feel good about the story and feel proud about sharing it with their children without feeling like they are doing something subversive,” she says. “I feel sad that this particular chain of events has led to such a mixed perception that doesn’t seem in any way keeping with the spirit of the books and the stories.”

Patrick Blennerhassett is an award-winning Canadian journalist and four-time published author. He is a Jack Webster Fellowship winner and a British Columbia bestselling novelist. His work has been published in The Guardian, Reader's Digest, The Globe & Mail, Business Insider, MSN and his commentary has appeared on the BBC and the CBC.

No comments:

Post a Comment