The Public Intellectual

Violence is the oxygen of authoritarianism. It is the symbolic and visceral breeding ground of fear, ignorance, greed and cruelty. It flourishes in societies marked by despair, ignorance, lies, hate and cynicism.

Violence — and especially the killing of children such as the mass killing that occurred this week at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, leaving at least 19 students dead — can’t be understood in the immediacy of shock and despair, however deplorable and understandable. The ideological and structural conditions that nourish and legitimate it have to be revealed both in their connections to power and in the systemic unmasking of those who benefit from such death-dealing conditions.

Among Democrats, the general response to mass violence in the U.S. is to call for more gun regulations and criticize the NRA, gun lobbies and the weapons industry. This is understandable given that the arms industry floods the United States with all manner of lethal weapons, pays out millions to mostly Republican politicians, and in the case of the NRA has sponsored an amendment banning “any federal dollars from being used to research gun injuries or deaths in the US.”

We should indeed criticize the gun lobby and arms industry, but this critique does not go far enough. The tragic murders of the 19 schoolchildren and two teachers in rural Texas at the hands of a young man who resorted to a horrific act of violence — and the killing of Black shoppers in a Tops grocery store in Buffalo by a hate-filled racist and self-proclaimed fascist — represent the end points of a culture awash in guns and violence, a society that nourishes and rewards the gun industries, and values the accumulation of profits over human needs. All of the latter is amplified by a modern Republican Party that accelerates a gun culture, revels in violence as a form of political opportunism, strips young people of crucial social provisions, and enables a culture of lies that make it difficult to discern the truth from falsehoods, good from evil. New York Times columnist Charles Blow rightly claims that “The Republican Party has turned America into a killing field.”

In the current historical moment, the market-driven values of “freedom,” choice and rugged individualism have merged with the concentration of power in the hands of the super-rich and corporations, an unbridled individualism, and a culture of terror and fear. One consequence is that the corruption of politics as big money is used to pay off politicians while using a corporate-controlled media to flood the culture with the notion that individual liberty is synonymous with unfettered gun rights. How else to explain that “Gun rights groups set new records for lobbying in 2021, spending over $15 million, with GOP Sen. Ted Cruz the biggest recipient,” as Ruth Ben-Ghiat wrote this week. It is not surprising that Cruz responded to the mass shooting in a Texas elementary school by declaring that one way to solve the problem of school violence was to arm teachers. It is worth noting that, according to Al Jazeera, “Sales of weapons and military services by the world’s 100 biggest arms companies reached a record $531bn in 2020.”

While the power of the NRA, arms dealers such as Lockheed Martin — the largest war industry in the world — and the military-industrial complex to shape politics and a permanent war economy is indisputable, this is only one register of a form of gangster capitalism that believes that market values, which privatize, commodify, and commercialize all social relations, are more important than addressing vital human needs, crucial social problems and the public good. This is a logic that suppresses human rights, views the struggle for social justice as a scourge, and cancels out the future for young people. William Greider in his book Who Will Tell the People, published in 1992, stated that if the U.S. lost its civic faith in the promise of democracy, it “has the potential to deteriorate into a rather brutish place, ruled by naked power and random social aggression.” Greider’s words were not only prescient, they capture the loss of vision and cult of authoritarianism at work in the United States.

Under neoliberalism, democratic life has no vision and no meaningful ideological civic anchors. Neoliberalism strips society of both its collective conscience and democratic communal relations. Violence proliferates in a society when justice is corrupted and power works to produce mass forms of historical and social amnesia largely aimed at degrading society’s critical and moral capacities.

There are more guns in circulation in the U.S. than people in a country of 325 million. The U.S. constitutes 5 percent of the world’s population and owns 25 percent of all guns on the globe. Judd Legum in Popular Information reports that in 2020, “39,695,315 guns were sold to civilians.” He notes further that this is an alarming figure given that “firearm ownership rates appear to be a statistically significant predictor of the distribution of public mass shooters worldwide.” Equally significant but not surprising is the fact that “More Americans have died from gunshots in the last 50 years than in all of the wars in American history,” according to NBC News. The Pew Research Center reported, “More Americans died of gun-related injuries in 2020 than in any other year on record.” What emerges from these figures and the relentless mass shootings in which young people have become an increasing target is the question of what kind of society has the United States become, and what are the broader economic, political and social forces that produce massive violence and its increasing collapse into authoritarianism?

As horrific as these figures are, the backdrop to the politics and plague of violence in the United States is rarely a subject of debate in the mainstream media. Even as specific policies are debated, what is ignored is a neoliberal economic system that feeds on self-interest, inequality, cruelty, punishment, precarity and loneliness. Neoliberal society fuels a criminogenic system that celebrates violence both as a source of pleasure and as an organizing principle of governance.

Neoliberal capitalism has given rise to a carceral state that criminalizes the behavior of young people, while filling the prisons with poor people of color, destroying their families and their futures. This is a system so cold-hearted that it refuses to renew the Child Tax Credit, pushing 3 million children below the poverty line.Young people are being killed in spaces that are supposed to protect them. In an age of fascist politics, mass violence has become normalized and is nourished by a culture of conspiracy theories.

The U.S. is the only country in the world where children as young as 13 are sentenced to prison without any chance of parole. Such policies are just one register of the slow and silent state violence waged against young people that works in tandem with the mass violence that is produced by a society in which injustice, poverty, fear and racial cleansing are central modes of governance. The irony here is that the current white supremacist Republican Party now claims it is the party dedicated to protecting children. This claim is ludicrous when tested against a party that bans books, models schools after prisons, demonizes transgender youth, assaults reproductive rights, and consistently puts policies in place that undermine efforts to lift children and their families above the poverty line.

Domestic terrorists now parade as politicians, and white supremacists dominate the Republican Party and revel in a civically depleted culture that has abandoned justice, ethics and hope for the corrupt currencies of wealth, power and self-aggrandizement. Increasingly young people are the targets of a form of gangster capitalism that has written them out of the script of democracy, placed them at the mercy of politicians who are self-proclaimed white Christian nationalists, and abandoned them through institutions that have broken from the social contract. Increasingly, they are stripped of their dignity, hopes, and in too many cases, their lives. This is the death machine of social abandonment and terminal exclusion that creates the conditions for blood to flow in the streets, schools, malls, supermarkets, churches, mosques and synagogues.

Young people are being killed in spaces that are supposed to protect them. In an age of fascist politics, mass violence has become normalized and is nourished by a culture of conspiracy theories, moral indifference, corrupt politicians, a social media that trades in hate, the normalization of mass shootings, and a grotesque public silence in the face of massive inequalities in wealth and power.

In such a context, it is not surprising that an increasing number of Republicans support violence as a tool for resolving political issues. It gets worse. The Washington Post has reported that, “1 in 3 Americans say they believe violence against government can at times be justified.” Violence has become so widespread that it both neutralizes the public’s sense of moral outrage and shatters their bonds of solidarity. As society is increasingly militarized under neoliberalism, violence becomes the solution for everything. This is especially dangerous for those individuals who feel isolated and lonely in a society that atomizes everything. Some of these individuals turn to the internet and social media in search of community, often to be radicalized by white supremacist conspiracy theories, as was the case with the Buffalo shooter.

The culture of violence has intensified since the 1980s and has found a privileged place in the cult of authoritarianism in the United States. It is embraced, legitimated and endorsed by a Republican Party that uses gun violence and mass school shootings as part of a poisonous script designed, as Ruth Ben-Ghiat argues to transform “public schools into death traps as part of a deliberate strategy to create an atmosphere of fear and suspicion conducive to survivalist mentalities and support for illiberal politics.”

Gun violence cannot be abstracted from a broader culture of violence and authoritarianism that calls for more gun ownership, more police and more national security. Moreover, both the gun industry and right-wing politicians who benefit from its profits are well aware fear and extremism sell more guns and generate lucrative markets for the merchants of death. The right-wing response to school shootings is as disingenuous as it is morally corrupt. In order to feed the coffers of the surveillance industry and other merchants of death, it calls for turning schools into armed camps, awash with high-tech security systems, more police, and more firearms for teachers while increasingly defining the purpose and meaning of schools through the language of a military culture. Such actions both cultivate a mass consciousness that worships violence even as it bemoans the terrible price it enacts on human life, especially when children become collateral damage in such a culture. The cult of violence in the U.S. is inseparable from cult of authoritarianism and the rise of neoliberal fascism.

In moments like these, we all must remember that justice is partly dependent upon the merging of civic courage, historical understanding, a critical education and robust mass action. There is a long history of resistance in the U.S. that is under siege and is being erased from schools, books and libraries by right-wing Republican politicians and their followers. This is not only an assault on historical consciousness; it’s also an assault on thinking itself, and the very ability to recognize injustice and the tools needed to oppose it. One consequence is that neoliberal authoritarianism now thrives in an ecosystem of historical amnesia and has become an accelerating agent of violence.

Authoritarianism as a death machine thrives by hiding in the language of common sense and the discourses of fear, terror and moral panic. As it becomes more widespread, it is normalized, becoming all the more destructive. Normalization is a form of mystification, and it can be seen in the way in which the larger forces behind mass shootings such as those at Tops supermarket and in the Texas school are often reduced to personal stories of individual grief and narratives limited to the assailants’ lives. As structural conditions are obscured, connecting the dots to a broader culture of violence becomes more difficult.

Hiding behind a rhetoric in which the political collapses into the personal and private troubles are removed from broader systemic considerations, power now functions in the service of a cabal of religious fundamentalists, charlatans of mass ignorance, the financial elite, and the corporate-controlled cultural apparatuses that trade in dishonesty, the spectacle of violence, and the demonization and dehumanization of anyone who is not a white Christian. Even worse, the modern Republican Party not only endorses calls for violence by members of its own party, including those made by Paul Gosar, Marjorie Taylor Greene, and others, but it has also become a party that openly views violence as a legitimate way to secure its desired political outcomes — to seize power and destroy democracy. Rather than being alarmed by violence, the Republican Party has created the conditions that suggest it wishes for even more. As Charles Blow observes, trading in fear and paranoia, the Republican Party terrorizes the public by claiming that “criminals are coming to menace you, immigrants are coming to menace you, a race war (or racial replacement) is coming to menace you and the government itself may one day come to menace you. The only defense you have against the menace is to be armed.” The only solution is to not only accept the American way of violence and death but to affirm it, be complicit with it, and in doing so legitimate it.

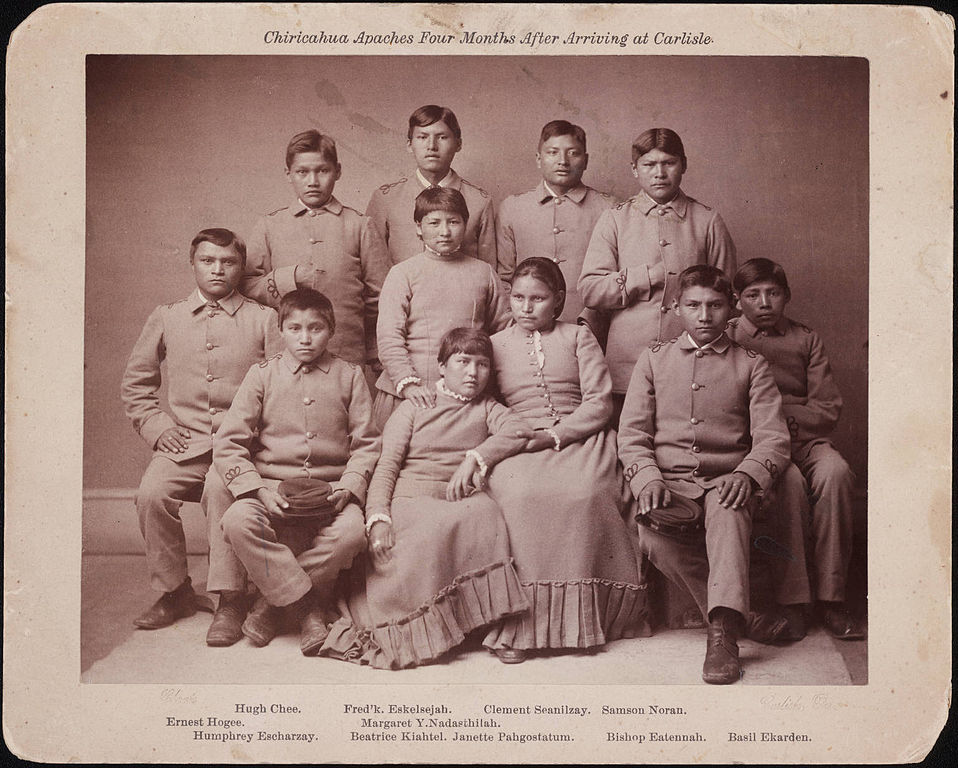

The killing of children turns this invisible scourge of power and its poisonous instruments on its head, if only for a moment, because of the shock of the unimaginable, gesturing at its roots the workings of current political and economic formations that function as a lethal force that turns everything into ashes. Such horrors cry out for connecting the endless threads of violence that mark the brutality waged against women, transgender youth, Black people, Indigenous people, undocumented immigrants, youth of color, disabled people, the environment, and all those considered disposable in this neo-fascist social order.As society is increasingly militarized under neoliberalism, violence becomes the solution for everything.

Against this authoritarian death machine, we all need to mobilize to turn despair into militant hope, critical analysis into action, and individual anger into collective struggles that refuse the seductions of gangster capitalism and its rebranded fascism.

On multiple fronts, youth are already at the forefront of this organizing. After the mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, in 2018, youth rose up against gun violence in unprecedented ways, creating the March for Our Lives and connecting the issue of school shootings with police violence, racial justice, and other urgent issues.

Youth are also speaking out and rising up in monumental ways regarding the climate crisis, racial justice, immigration justice, war, prisons, and more. Adults would do well to recognize, bolster and amplify these forms of youth activism to help them grow and gain momentum.

History is open, and the signposts of the current moment are waiting for a radical change in consciousness, institutions and action. How much more blood will flow in schools and other places where young people and adults live their lives before a sufficiently powerful mass movement arises to put an end to this capitalist architecture of ideological and institutional violence?

Resistance is the only option, and it has to be educational, structural, bold and disruptive — far removed from the weak call for a revitalized electoral politics or moderate gun reforms. Resistance has to breathe anger, outrage, and mediate a sense of moral righteousness through a mass movement for economic, environmental and social justice.

Frederick Douglass was right when he stated: “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will. Find out just what any people will quietly submit to, and you have found out the exact measure of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them, and these will continue till they are resisted with either words or blows, or with both. The limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress.”

How many more deaths can this country endure, how many more innocent children will be killed before a mass movement arises that can bring this brutal social order to an end?

Henry A. Giroux currently holds the McMaster University Chair for Scholarship in the Public Interest in the English and Cultural Studies Department and is the Paulo Freire Distinguished Scholar in Critical Pedagogy. His most recent books include: American Nightmare: Facing the Challenge of Fascism (City Lights, 2018); The Terror of the Unforeseen (Los Angeles Review of books, 2019), On Critical Pedagogy, 2nd edition (Bloomsbury, 2020); Race, Politics, and Pandemic Pedagogy: Education in a Time of Crisis (Bloomsbury 2021); and Pedagogy of Resistance: Against Manufactured Ignorance (Bloomsbury 2022). Giroux is also a member of Truthout’s Board of Directors.