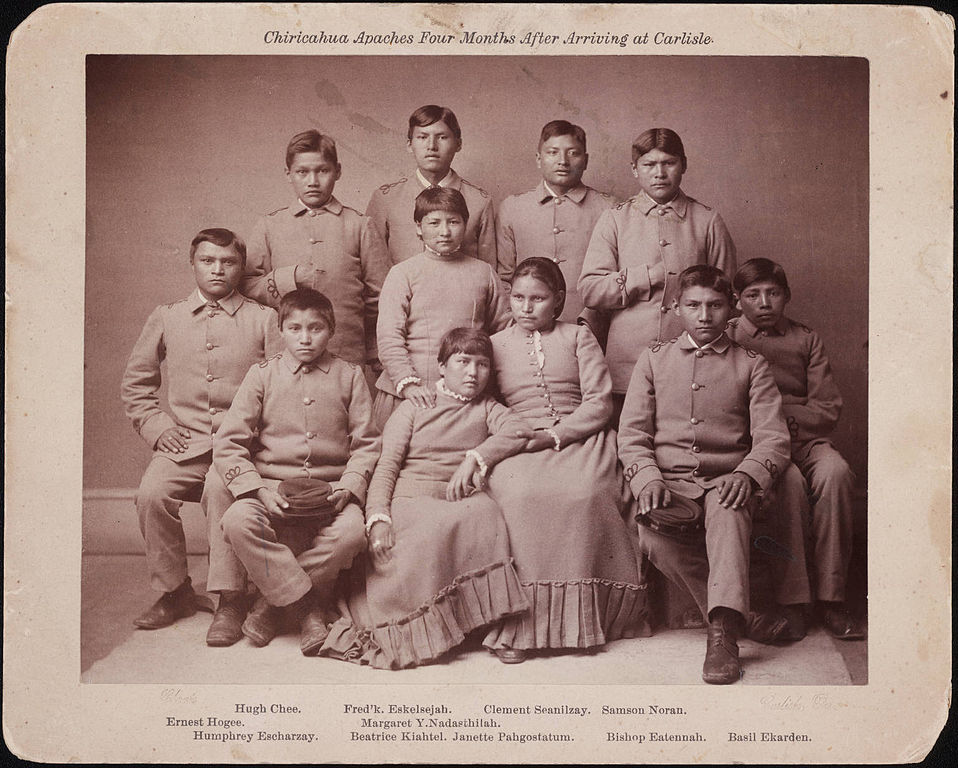

"Chiricahua Apaches Four Months After Arriving at Carlisle," black-and-white photographic portrait of a group of Apaches at the Carlisle boarding school. Image courtesy of the Richard Henry Pratt Papers, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Opinion.

The 106-page Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report released on May 11 provides a glimpse into the deliberate intention of the federal government to disrupt the Native American family structure through assimilation. The report says the government’s plan involved the permanent breaking of family ties.

A section of the report, Section 7: Federal Indian Boarding School System Framework, reads: “The Department has stated it was ‘indispensably necessary that [the Indians] be placed in positions where they can be controlled, and finally compelled, by stern necessity, to resort to agricultural labor or starve,’ later adding that ‘[i]f it be admitted that education affords the true solution to the Indian problem, then it must be admitted that the boarding school is the very key to the situation.’”

Reading that section of the report brought back memories of the day I first met Dr. Suzanne Cross (Saginaw Chippewa Indians) in the late 1990s when I served on the Native American subcommittee of the Michigan Department on Aging. Dr. Cross is an assistant professor emeritus at Michigan State University and served as a consultant to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS). She came to our subcommittee to discuss the work she had done on her doctoral dissertation on historical trauma. The conversation quickly moved to the historical trauma associated with Indian boarding schools.

Several adults told stories of abuse they suffered at Indian boarding schools, and others shared how boarding schools affected their families. One Ojibwa woman shook and wept, telling us how her mother never hugged her during her life. The mother had learned during her years at an Indian boarding school that she should never hug or show physical affection.

Last week's release of the report on the purposeful and deliberate plan by the federal government to destroy Native families also brought back memories of an interview I did with American Indian Movement co-founder Dennis Banks (Ojibwa) in the fall of 2009 at Grand Valley State University. During the interview, Banks recounted his experiences attending various Indian boarding schools. He told me the experience caused him to maintain an indifferent attitude towards his mother because he felt she had abandoned him during the years he attended Indian boarding schools.

Banks recalled on certain occasions, school officials would announce a mail call so that students could get mail from home. He would show up, but he never received any mail. He felt as if his mother did not love him.

Years passed by and he eventually was able to go home when he was in his late teen years. He said the first day home was awkward, but on the second day home, his mother made him a blueberry pie because she knew it was his favorite. He felt then perhaps things could return to normal. So, he began talking to her and asked her why didn’t she ever send him any letters or try to bring him home. She told him she did.

He did not believe her.

For the rest of their lives together, he told me, he would look at his mother and have a sense of indifference towards her. This feeling lasted until she died.

Decades later, while he was in his 70s, Banks saw an Internet advertisement with information about how he could obtain his own Indian boarding school records. He followed through on the offer and received several boxes with his school records.

In the boxes, Banks found 14 unopened letters from his mother. He took them to his mother’s grave, where he sat in a lawn chair reading them one by one. Inside of one of the letters was a money order to pay for a bus ticket home for him.

In that moment, Banks, one of the greatest Native American warriors of the last century, wept at his mother’s grave and asked her for forgiveness. He had been lied to by the Indian boarding school officials, not his mother.

As I interviewed Banks at the university in my hometown, I recognized that his inner child, which had been wounded for decades, still resented the policy set forth by the federal government to destroy the very fabric of Native American families.

Banks’ story is just one among a multitude of survivor stories about how Indian Boarding Schools tore Native families apart.

“There's not a single American Indian, Alaskan Native, or Native Hawaiian in this country whose life hasn't been affected by these schools,” Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs Bryan Newland said during the press conference about the investigation and report last week.“That impact continues to influence the lives of countless families, from the breakup of families and tribal nations, to the loss of languages and cultural practices and relatives. We haven't begun to explain the scope of this policy until now.”

During last week’s press conference, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) said, “The consequences of federal Indian boarding school policies, including the intergenerational trauma caused by forced family separation and cultural eradication, which were inflicted upon generations of children, as young as four years old, are heartbreaking and undeniable. When my maternal grandparents were only eight years old, they were stolen from their parents, culture, and communities and forced to live in boarding schools until the age of 13. Many children like them never made it back to their homes.”

The Interior’s report calls for the continuation of the investigation of boarding schools with many more survivor stories to be collected as part of Secretary Haaland's yearlong tour called "The Road to Healing."

For countless boarding school survivors and their families, the road to healing will be paved with pain. Telling their stories will be haunting and painful, but hopefully it will give them the same type of release that Dennis Banks felt as he sat by his mother’s grave in a lawnchair, reading her long lost letters and confronting the past.

About The Author

Levi Rickert (Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation) is the founder, publisher and editor of Native News Online. Rickert was awarded Best Column 2021 Native Media Award for the print/online category by the Native American Journalists Association. He serves on the advisory board of the Multicultural Media Correspondents Association. He can be reached at levi@nativenewsonline.net.

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/2022/01/did-canadian-government-build-schools.html

No comments:

Post a Comment