Jasmin Merdan//Getty Images

A branch of math called chaos theory looks at how small changes to a system can result in unpredictable behavior.

Chaos theory explains how complex systems work in multiple fields, including astrophysics, climate change, and neuroscience.

Chaos doesn’t always mean systems are totally unpredictable. Researchers have identified patterns that help them predict overall movements.

“Does the flap of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas?” Might sound like the type of question posed by science fiction explorers to reveal the precarity of time travel, but in reality it’s the title of an MIT professor’s 1972 paper presented in a Sheraton conference room to members of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Meteorologist Edward Lorenz wrote the paper, and while the concept seems far-fetched, the analogy actually highlights an idea underlying everything from planetary motion to climate change: chaos.

More precisely, this example works to explain a kind of math called chaos theory, which looks at how small changes made to a system’s initial conditions—like the extra gust of wind from a butterfly’s wings—can result in seemingly unpredictable behavior. (For example, a tornado in Texas.)

While mathematicians wouldn’t necessarily call themselves chaos theorists today, the theory does play a role in the study of dynamical systems, which Kevin Lin, associate professor of math at the University of Arizona, says helps us study everything from climate change to neuroscience.

“Chaos is a fact of life … and a part of dynamical systems theory,” Lin explains to Popular Mechanics in an email. “Some systems are inherently chaotic, while others are not. Many [mathematicians] are also very interested in how certain systems can exhibit both types of behavior, and transition between these different regimes under different conditions.”

The Origins of Chaos Theory

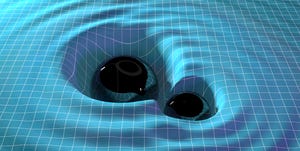

While Lorenz might be known for coining the “Butterfly Effect” in relation to chaos theory, Lin says that the discovery of chaos theory actually dates back to the 1890s and a mathematician and physicist named Henri Poincaré. In his relatively short life, Poincaré made an impact on a wide range of topics, from gravitational waves to quantum mechanics.

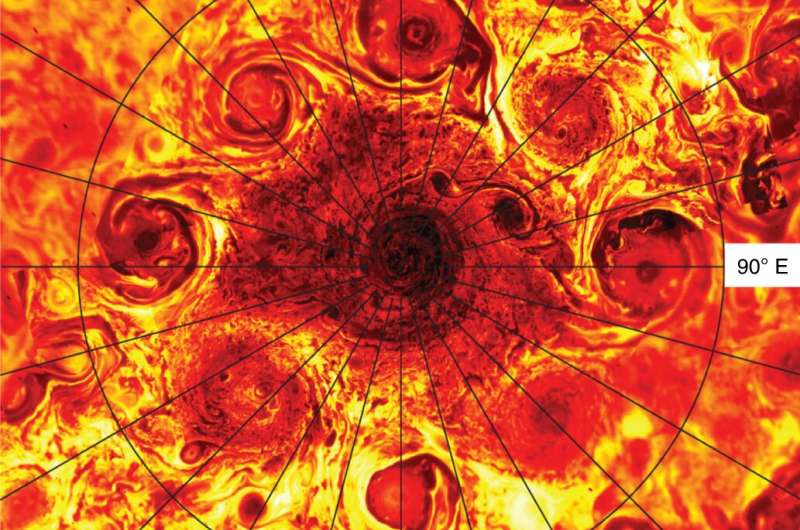

These efforts also included explaining why the famed three-body problem—which tries to explain the motion of three planetary bodies orbiting each other—could not be solved. Chief among those reasons was that the system was sensitive to small, unpredictable perturbations ... AKA, chaos.

photovideostock//Getty Images

“Prior to Poincaré, mathematicians studying dynamics, i.e., the behavior of systems governed by differential equations … focused on one solution at a time,” Lin says. “Poincaré introduced concepts and tools for thinking about dynamics ‘globally,’ that is, how whole sets of solutions evolve in time.”

Despite not being first to the idea, it was Lorenz’s discovery of chaos that “broke into popular culture,” Mark Levi, professor and head of the math department at Penn State, tells Popular Mechanics in an email.

Butterfly analogy aside, Lorenz’s discovery was actually made when using an early computer to study weather models. When re-running a weather simulation from partway through its calculation, Lorenz was surprised to see that the same data and conditions had somehow made drastically different predictions. As it turns out, the difference came down to the significant digits used by the machine for calculation, demonstrating that systems like weather patterns can be very sensitive to their initial conditions.

Is Chaos Always Unpredictable?

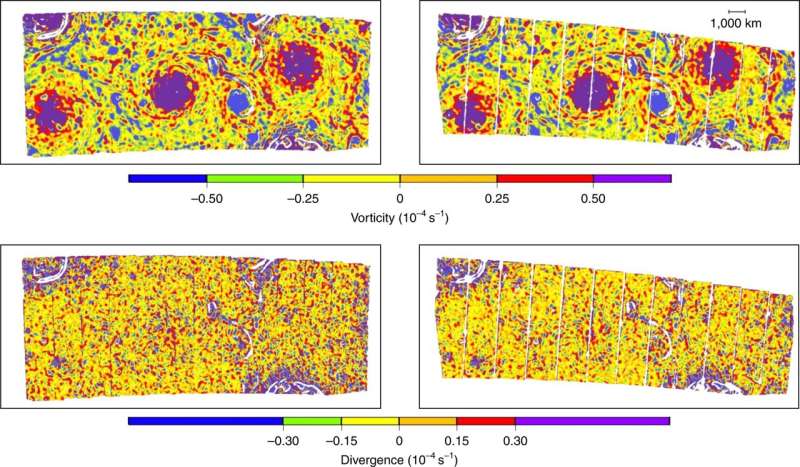

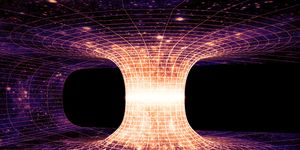

While many natural systems have chaotic behavior, this doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re all unpredictable, or non-deterministic. When studying how these systems behave in phase space—a kind of multidimensional map of the system’s states through time—researchers have identified patterns that help them predict the overall movement of a system.

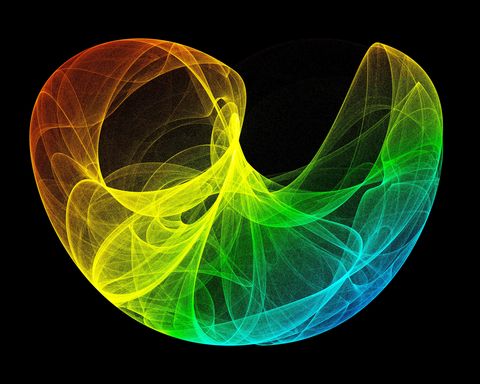

Artwork of a Lorenz Attractor, named after Edward Lorenz, who developed a system of ordinary differential equations. The Lorenz attractor is a set of chaotic solutions of the Lorenz system which, when plotted, resemble a butterfly or figure eight. For the system’s sensitivity to initial conditions, Lorenz coined the term butterfly effect. This effect is the underlying mechanism of deterministic chaos.

Like gravity attracts planetary bodies or an ocean current directs sea creatures, researchers found that there are invisible “attractors” that chaotic systems are drawn to. These attractors look different for different systems, but often take the form of recursive, fractal shapes.

Sadly, finding an attractor for every type of chaotic system is a bit of pipe dream, says Levi.

“Even ridiculously simple systems, such as a pendulum with an oscillating pivot, are chaotic and too complex for complete understanding—never mind the motion of the atmosphere or the oceans,” he says.

How Chaos Helps Us Today

Chaos theory may be fairly theoretical at this point, but the study of dynamical systems is much more tangible, Lin says. As part of his research, Lin uses dynamics to study how seemingly random firings of neurons in our brains transform into complex information systems.

“The brain is an example of a system that is highly unpredictable when you look at it closely,” he says. “Nevertheless, it functions very reliably. Therein lies a conundrum: how can something seemingly random reliably encode and process information?”

Scientists and mathematicians don’t have a clear answer to this question yet, but Lin says he’s enjoying the ride through chaos. “At least for me,” Lin says,“it’s fun!”

‘Grandfather Paradox’ Doesn’t Rule Out Time Travel

‘Grandfather Paradox’ Doesn’t Rule Out Time Travel Quantum Physics May Finally Explain Consciousness

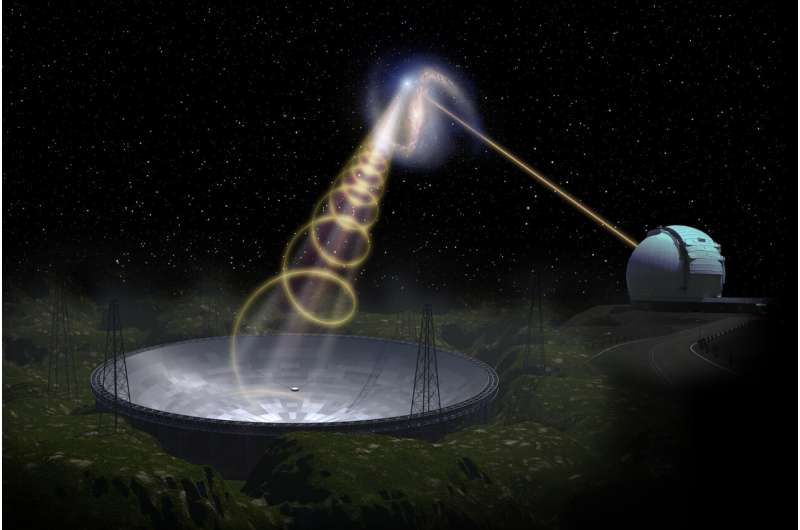

Quantum Physics May Finally Explain Consciousness These Waves Could Reveal the Invisible Universe

These Waves Could Reveal the Invisible Universe Black Holes Could Solve the Mystery of Dark Matter

Black Holes Could Solve the Mystery of Dark Matter The Standard Model of Particle Physics, Explained

The Standard Model of Particle Physics, Explained The Universe Changes the Laws of Physics By Itself

The Universe Changes the Laws of Physics By Itself